Dairi Storytelling and Stories in the Batak Reader of Herman Neubronner Van Der Tuuk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pengumuman Abstrak PRASASTI III Yth. Bapak/Ibu Penulis

THE 3rd PRASASTI INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR CURRENT RESEARCH IN LINGUISTICS Secretariat: Doctoral Program in Linguistics, Postgraduate, Universitas Sebelas Maret Jl. Ir. Sutami 36A Kentingan, Surakarta 57126, Telp/Fax (0271) 632450 Psw 377 Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] Website: s3linguistik.pasca.uns.ac.id Nomor : 05/PRASASTI/III/S3LG/2016 s3s3linguistik.pasca.uns.ac.idLampiran : 1 (satu) eksemplar Hal : Pengumuman abstrak PRASASTI III Yth. Bapak/Ibu Penulis Makalah Seminar Internasional PRASASTI III Dengan hormat, Bersama ini kami sampaikan bahwa abstrak Bapak/Ibu dinyatakan diterima untuk dapat disajikan/ dipresentasikan pada Seminar Internasional PRASASTI III yang diselenggarakan oleh Program Studi S3 Linguistik Pascasarjana Universitas Sebelas Maret. Sehubungan dengan hal tersebut, dimohon Bapak/Ibu memperhatikan poin-poin sebagai berikut. 1. Mengirimkan abstrak beserta fullpaper sesuai dengan ketentuan melalui email [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) dengan subjek dan nama file Nama_FullPaperPrasasti3 dalam format doc. atau rtf (jangan mengirim pdf) paling lambat pada tanggal 8 Juli 2016. 2. Melakukan pembayaran sesuai dengan ketentuan. 3. Mengisi formulir pendaftaran melalui yang formulirnya akan kami kirimkan melalui email dan/atau melalui website s3linguistik.pasca.uns.ac.id 4. Mengirim bukti pembayaran melalui email [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) dengan subjek Pembayaran_Nama_NoHP 5. Bukti transfer mohon disimpan dan dibawa pada saat seminar (2-3 Agustus 2016) Berikut kami lampirkan daftar nama penulis abstrak yang dinyatakan lolos seleksi untuk menuliskan fullpaper. Demikian pemberitahuan dari kami. Kami sampaikan terima kasih atas kerjasama Bapak/Ibu. Kami mengharapkan kehadiran Bapak/Ibu pada acara seminar tersebut tanggal 2 – 3 Agustus 2016, di Syariah Hotel Solo. -

![Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4203/arxiv-2011-02128v1-cs-cl-4-nov-2020-234203.webp)

Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020

Cross-Lingual Machine Speech Chain for Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks Speech Recognition and Synthesis Sashi Novitasari1, Andros Tjandra1, Sakriani Sakti1;2, Satoshi Nakamura1;2 1Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan 2RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project AIP, Japan fsashi.novitasari.si3, tjandra.ai6, ssakti,[email protected] Abstract Even though over seven hundred ethnic languages are spoken in Indonesia, the available technology remains limited that could support communication within indigenous communities as well as with people outside the villages. As a result, indigenous communities still face isolation due to cultural barriers; languages continue to disappear. To accelerate communication, speech-to-speech translation (S2ST) technology is one approach that can overcome language barriers. However, S2ST systems require machine translation (MT), speech recognition (ASR), and synthesis (TTS) that rely heavily on supervised training and a broad set of language resources that can be difficult to collect from ethnic communities. Recently, a machine speech chain mechanism was proposed to enable ASR and TTS to assist each other in semi-supervised learning. The framework was initially implemented only for monolingual languages. In this study, we focus on developing speech recognition and synthesis for these Indonesian ethnic languages: Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks. We first separately train ASR and TTS of standard Indonesian in supervised training. We then develop ASR and TTS of ethnic languages by utilizing Indonesian ASR and TTS in a cross-lingual machine speech chain framework with only text or only speech data removing the need for paired speech-text data of those ethnic languages. Keywords: Indonesian ethnic languages, cross-lingual approach, machine speech chain, speech recognition and synthesis. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This Chapter Presents Five Subtopics

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This chapter presents five subtopics, namely; research background, research questions, research objective, research limitation and research significance. 1.1 Research Background Language is essentially a speech of the mind and feeling of human beings on a regular basis, which uses sound as a tool (Ministry of National Education, 2005: 3). Language is a structure and meaning that is free from its users, as a sign that concludes a goal (HarunRasyid, Mansyur&Suratno 2009: 126). Language is a particular kind of system that is used to transfer the information and it is an encoding and decoding activity in order to get information (Seken, 1992). The number of languages in the world varies between (6,000-7,000) languages. However, the right estimates depend on arbitrary changes between various languages and dialects. Natural language is sign language but each language can be encoded into a second medium using audio, visual, or touch stimuli, for example, in the form of graphics, braille, or whistles. This is because human language is an independent modality. All languages depend on a symbiotic process to connect signals with certain meanings. In Indonesia there are many very beautiful cities and many tribes that have different languages and are very interesting to learn. One of the cities to be studied is Banyuwangi Regency. Banyuwangi Regency is a district of East Java province in Indonesia. This district is located in the easternmost part of Java Island. Banyuwangi is separated by the Bali Strait from Bali. Banyuwangi City is the administrative capital. The name Banyuwangi is the Javanese language for "fragrant water", which is connected with Javanese folklore on the Tanjung. -

The Structure of the Toba Batak Conversation Hilman

Singapore THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS Hilman Pardede, Padang Sidempuan, May 25, 1960. He graduated from PressInternational English Program of North Sumatera THE STRUCTURE University in 1987. In the year of 1992 he took Magister Program in IKIP Malang, OF THE TOBA BATAK then he went to Doctoral Program in linguistics at North Sumatera University CONVERSATION in the year of 2007. In 2008, he attended a Sandwich Program in Aurbun THEBATAK CONVERSATION TOBA OF University, Alabama, USA. In 2010, he was a speaker in the International Seminar in Trang, Thailand. He presented a paper entitled “Adjecancy Pair in Toba STRUCTURE THE Batak”. HILMAN PARDEDE This book is about the structure of the Toba Batak Conversations. The structures are categorized as interaction and linguistics. The interaction structures are restricted to adjacency pairs and turn-taking, and the linguistic structure to phonological, grammatical and semantic completion point. There are some negative cases in the structure of Toba Batak conversations. These negative cases result from the Conversation HILMAN PARDEDE Analysis (CA) as a tool used to explain the interaction and linguistic structure in Toba Batak phenomena. ISBN: Singapore International Presss Singapore International Press 2012 THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS Hilman Pardede Singapore International Press 2012 THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS By Hilman Pardede, Ph.D A Lecturer in English Language Teaching for Universitas HKBP Nommensen Pematangsiantar – Medan, Indonesia @Hilman Pardede, Ph.D ISBN: First Edition 2012 Singapore Do not circulate this book or any part of it in any binding or form by means of any equipment without any legal permission from Hilman Pardede, Ph.D! Prodeo et Patricia 2 For Lissa Donna Manurung and Claudia Benedita Pardede 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deep gratitude to all those who lent their assistance and advice in the preparation and publication of this book. -

MEDAN BAHASA JURNAL ILMIAH KEBAHASAAN Volume 6, No

ISSN 1907—1787 MEDAN BAHASA JURNAL ILMIAH KEBAHASAAN Volume 6, No. 2, Edisi Desember 2012 Penanggung Jawab: Amir Mahmud • Pemimpin Redaksi: Awaludin Rusiandi • Sekretaris Redaksi: Ai Siti Rohmah • Penyunting Ahli: Achmad Effendi Kadarisman (Etnolinguistik/Universitas Negeri Malang), Kisyani-Laksono (Dialektologi/Universitas Negeri Surabaya) • Penyunting Pelaksana: Anang Santosa, Khoiru Ummatin, Arif Izzak, Hero Patrianto • Mitra Bestari: Tri Mastoyo Jati K. (Tata Bahasa/Universitas Gadjah Mada), Ni Ketut Mirahayuni (Analisis Wacana/Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Surabaya) • Juru Atak: Punjul Sungkari • Distribusi: Rahmidi Penerbit Balai Bahasa Provinsi Jawa Timur Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Alamat Redaksi Balai Bahasa Provinsi Jawa Timur Jalan Siwalanpanji II/1, Buduran, Sidoarjo 61252 Telepon/Faksimile (031) 8051752 Pos-el: [email protected] Jurnal Medan Bahasa terbit dua kali setahun pada bulan Juni dan Desember. Jurnal ini berisi tulisan ilmiah berupa hasil penelitian, kajian dan aplikasi teori, gagasan konseptual, serta resensi buku dengan wilayah kajian kebahasaan. Redaksi jurnal Medan Bahasa mengundang para pakar, dosen, guru, dan peneliti bahasa untuk menulis artikel ilmiah yang berkaitan dengan masalah kebahasaan. Naskah yang masuk disunting secara anonim oleh penyunting ahli. Untuk keseragaman format, penyunting pelaksana berhak melakukan perubahan tanpa mengubah isi tulisan. ISSN 1907—1787 PRAKATA Jurnal Medan Bahasa Volume 6, Edisi Desember 2012, menyajikan sepuluh artikel hasil penelitian dan kajian. Artikel-artikel yang dimuat dalam edisi ini didominasi oleh penelitian atau kajian terhadap bahasa daerah; tujuh artikel meneliti atau mengkaji bahasa daerah, dua artikel melibatkan bahasa asing, dan satu artikel mengkaji penggunaan bahasa Indonesia di ranah elektronik. Artikel pertama berjudul “Derivasi Transposisional pada Kategori Verba Denominal dalam Bahasa Osing” ditulis oleh Asrumi. -

Looking Into the Language Status of Osing with a Contrastive Analysis of the Basic Vocabulary of Osing and Malang Javanese

Parole: Journal of Linguistics and Education, 10 (2), 2020, 87-96 Available online at: https://ejournal.undip.ac.id/index.php/parole Looking into the Language Status of Osing with a Contrastive Analysis of the Basic Vocabulary of Osing and Malang Javanese Ika Nurhayani*, Hamamah Hamamah, Dwi I. N. A. Mardiana, Ressi M. Delijar Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO Osing is a language spoken by the majority of people in Banyuwangi, East Java. However, there is obscurity on its status whether it is considered as one of the Javanese dialects or as an independent language originated in Java. Paper type: Some noted that the Osing is another version of Javanese, while the people Research Article living in the Banyuwangi Region regard the Osing as a distinct identity that differentiates it from the rest of the Javanese speaking regions in Central and Article history: East Java. Hence, this research aims to provide linguistic evidence on the Received 04/02/2020 lexical differences between the Osing and Malang Javanese. The research is Revised 22/06/2020 significant because there is no previous research that provides linguistic Published 26/10/2020 evidence on the differences between the Osing and other Javanese dialects. Data of this study was obtained through eliciting the production of the basic Keywords: vocabulary of the Osing and Malang Javanese speakers. The findings of the Language Status Osing research provide evidence to the observation of previous linguists in that the Contrastive Analysis Osing is not a linguistically separate language of Javanese. Malang Javanese 1. Introduction Osing is a language spoken by 300.000 people in Banyuwangi (Eberhard, David M., Gary F. -

153 Natasha Abner (University of Michigan)

Natasha Abner (University of Michigan) LSA40 Carlo Geraci (Ecole Normale Supérieure) Justine Mertz (University of Paris 7, Denis Diderot) Jessica Lettieri (Università degli studi di Torino) Shi Yu (Ecole Normale Supérieure) A handy approach to sign language relatedness We use coded phonetic features and quantitative methods to probe potential historical relationships among 24 sign languages. Lisa Abney (Northwestern State University of Louisiana) ANS16 Naming practices in alcohol and drug recovery centers, adult daycares, and nursing homes/retirement facilities: A continuation of research The construction of drug and alcohol treatment centers, adult daycare centers, and retirement facilities has increased dramatically in the United States in the last thirty years. In this research, eleven categories of names for drug/alcohol treatment facilities have been identified while eight categories have been identified for adult daycare centers. Ten categories have become apparent for nursing homes and assisted living facilities. These naming choices function as euphemisms in many cases, and in others, names reference morphemes which are perceived to reference a higher social class than competitor names. Rafael Abramovitz (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) P8 Itai Bassi (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Relativized Anaphor Agreement Effect The Anaphor Agreement Effect (AAE) is a generalization that anaphors do not trigger phi-agreement covarying with their binders (Rizzi 1990 et. seq.) Based on evidence from Koryak (Chukotko-Kamchan) anaphors, we argue that the AAE should be weakened and be stated as a generalization about person agreement only. We propose a theory of the weakened AAE, which combines a modification of Preminger (2019)'s AnaphP-encapsulation proposal as well as converging evidence from work on the internal syntax of pronouns (Harbour 2016, van Urk 2018). -

Problematic Approach to English Learning and Teaching: a Case in Indonesia

English Language Teaching; Vol. 8, No. 3; 2015 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Problematic Approach to English Learning and Teaching: A Case in Indonesia Himpun Panggabean1 1 Universitas Methodist Indonesia, Medan, Indonesia Correspondence: Himpun Panggabean, Universitas Methodist Indonesia, Medan, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 29, 2014 Accepted: November 30, 2014 Online Published: February 13, 2015 doi:10.5539/elt.v8n3p35 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n3p35 Abstract This article deals with problematic approach to English learning and teaching due to misleading conception on the nature of English and on the process of acquiring it as well as the clues to the issues. The clues are: Firstly, English is not more difficult than any other languages, including Indonesian language, Bahasa Indonesia (Note 1). Secondly, there are two approaches that need considering in English instruction, grammar free and strict grammar approaches. The former is highly recommended for early age instruction and beginners whereas the latter is recommended for instruction for specific purposes. However the two approaches should collaborate and their applications should be based on needs analysis. Thirdly, Conflicting conception on whether L1 and L2 are the same processes should not deter the strategy of how language is acquired naturally. When proper conception on the nature of English is attained and it is approached properly, English subject is not burdensome and needs not be eliminated from Primary School curriculum, and there is no need to reduce time allotment for the subject in Senior High School as stipulated in Indonesian English curriculum amendment. -

1 Linguistic Analysis on Javanese Language

LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS ON JAVANESE LANGUAGE SELOGUDIG-AN DIALECT IN SELOGUDIG, PAJARAKAN, PROBOLINGGO Lusi Nur Aini (Corresponding Author) Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of Language and Literature Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jln. S. Supriadi No. 48 Malang 65148, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 82-301-732-015 E-mail: [email protected] Arining Wibowo Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of Language and Literature Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jln. S. Supriadi No. 48 Malang 65148, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 85-646-389-803 E-mail: [email protected] Maria G. Sriningsih Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of Language and Literature Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jln. S. Supriadi No. 48 Malang 65148, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 85-933-033-177 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Linguistic analysis is an analysis of language study which include language form, language meaning, and language in context. Study of linguistic can learn the kind of approaches in language. For example, grammar, language and culture, like the study of cultural discourses and dialects is the domain of sociolinguistics, which looks at the relation between linguistic variation and social structures. Language is one of human characteristics because people living with language. Indonesia is well known of one thousand islands country and as 1000 languages country. So, in Indonesia, there are many vernaculars from each ethnicity in every region of Indonesia. Javanese language has the most speakers of the existing another language speakers. As a language that has a lot of speakers, Javanese language has a lot of kinds or dialect forms as a result of the space and time process. -

World Directory of Minorities

World Directory of Minorities Asia and Oceania MRG Directory –> Indonesia –> Batak Print Page Close Window Batak Profile The 6 million or so Bataks (Indonesia Census, 2000) belong to one of about seven ethnic groups (Alas- Kluet, Angkola, Dairi, Karo, Mandailing, Simalungun and Toba) inhabiting the interior of Sumatera Utara Province south of Aceh. Their languages are within their own branch of Sumatran languages, part of the Austronesian family, and most of them live in the highlands, especially around Lake Toba, to the west of Medan. Mainly Christians (though a small percentage are Muslim), the Batak are organized along patriarchal group lines known as marga. This group owns land and does not permit marriage within it. The marga has proved to be a flexible social unit. Batak who resettle in urban areas, such as Medan and Jakarta, draw on marga affiliations for financial support and political alliances, reinforcing their ethnic identity. Historical context Indigenous minorities who have long inhabited the highlands of north-central Sumatra, the Bataks have lived in relative geographic isolation throughout much of history, though there are historical references to them going back to the thirteenth century. Their fighting traditions, and their reputation as cannibals, probably also helped to reinforce their relative isolation. This began to change in earnest at the start of the nineteenth century when the Bataks and the neighbouring Minangkabau minority – already Islamized – were involved in a series of conflicts. Some Bataks, such as the Mandailing, Angkola and Karo, began to convert, often then calling themselves Malay. The Dutch themselves were relatively late arrivals here, with the first Dutch missionaries only being sent from 1850, and the Bataks themselves only being completely subdued after what is sometimes referred to as the Batak war of 1872–94. -

A Grammar of Toba Batak Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

A GRAMMAR OF TOBA BATAK KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE TRANSLATION SERIES 13 H. N. VAN DER TUUK A GRAMMAR OF TOBA BATAK Springer-Science+Business Media, B.V. 1971 This book is published under a grant from the Netherlands Ministry of Education and Sciences The original title was : TOBASCHE SPRAAKUNST in dienst en op kosten van het Nederlandsch Bijbelgenootschap vervaardigd door H. N. van der Tuuk Amsterdam Eerste Stuk (Klankstelsel) 1864 Tweede Stuk (De woorden als Zindeelen) 1867 The translation was made by Miss Jeune Scott-Kemball; the work was edited by A. Teeuw and R. Roolvink, with a Foreword by A. Teeuw. ISBN 978-94-017-6707-1 ISBN 978-94-017-6778-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-017-6778-1 CONTENTS page Foreword by A. Teeuw XIII Preface to part I XL Preface to part II . XLII Introduction XLVI PART I THE SOUND SYSTEM I. SCRIPT AND PRONUNCIATION 1. WTiting . 3 2. The alphabet . 3 3. Anak ni surat . 4 4. Pronunciation of the a 5 5. Pronunciation of thee 5 6. Pronunciation of the o . 6 7. The relationship of ·the consona.n.ts to each other 7 8. Fusion of vowels . 9 9. wortl boundary . 10 10. The pronunciation of ?? . 10 11. The nasals as closers before an edged consonant 11 12. The nasals as closeTs before h . 12 13. Douible s . 13 14. The edged consonants as closers before h. 13 15. A closer n before l, r and m 13 16. R as closer of a prefix 14 17. -

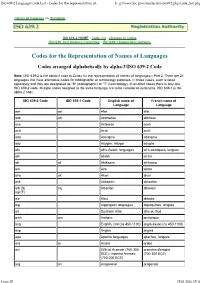

ISO 639-2 Language Code Lis

ISO 639-2 Language Code List - Codes for the representation of... h p://www.loc.gov/standards/iso639-2/php/code_list.php Library of Congress >> Standards IS0 639-2 HOME - Code List - Changes to Codes ISO 639 Joint Advisory Committee - ISO 639-1 Registration Authority Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages Codes arranged alphabetically by alpha-3/ISO 639-2 Code Note: ISO 639-2 is the alpha-3 code in Codes for the representation of names of languages-- Part 2. There are 21 languages that have alternative codes for bibliographic or terminology purposes. In those cases, each is listed separately and they are designated as "B" (bibliographic) or "T" (terminology). In all other cases there is only one ISO 639-2 code. Multiple codes assigned to the same language are to be considered synonyms. ISO 639-1 is the alpha-2 code. ISO 639-2 Code ISO 639-1 Code English name of French name of Language Language aar aa Afar afar abk ab Abkhazian abkhaze ace Achinese aceh ach Acoli acoli ada Adangme adangme ady Adyghe; Adygei adyghé afa Afro-Asiatic languages afro-asiatiques, langues afh Afrihili afrihili afr af Afrikaans afrikaans ain Ainu aïnou aka ak Akan akan akk Akkadian akkadien alb (B) sq Albanian albanais sqi (T) ale Aleut aléoute alg Algonquian languages algonquines, langues alt Southern Altai altai du Sud amh am Amharic amharique ang English, Old (ca.450-1100) anglo-saxon (ca.450-1100) anp Angika angika apa Apache languages apaches, langues ara ar Arabic arabe arc Official Aramaic (700-300 araméen d'empire BCE); Imperial Aramaic (700-300 BCE) (700-300 BCE) arg an Aragonese aragonais 1 von 15 15.01.2010 15:16 ISO 639-2 Language Code List - Codes for the representation of..