The Case of Osing in Banyuwangi, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D 328 the Bioregional Principal at Banyuwangi Region Development

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, November 26-28, 2019 The Bioregional Principal at Banyuwangi Region Development in the Context of Behavior Maintenance Ratna Darmiwati Catholic University of Darma Cendika, Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract The tourism, natural resources, local culture and Industries with the environment are the backbone of the government's foreign development in the region exchange. The sustainable development without the environment damaging that all activities are recommended, so that between the nature and humans can be worked simultaneously. The purpose of study is maintaining the natural conditions as they are and not to be undermined by irresponsible actions. All of them are facilitated by the government, while maintaining the Osing culture community and expanding the region and make it more widely known. The maintenance of the natural existing resources should be as good as possible, so that it can be passed on future generations in well condition. All of the resources, can be redeveloped in future. The research method used qualitative-descriptive-explorative method which are sorting the datas object. The activities should have involved and relevant with the stakeholders such as the local government, the community leaders or non-governmental organizations and the broader community. The reciprocal relationships between human beings as residents and the environment are occurred as their daily life. Their life will become peaceful when the nature is domesticated. The nature will not be tampered, but arranged in form of human beings that can be moved safely and comfortably. Keywords: The Culture, Industry, Natural Resources, Tourism. -

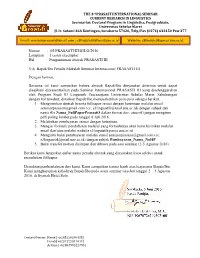

Pengumuman Abstrak PRASASTI III Yth. Bapak/Ibu Penulis

THE 3rd PRASASTI INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR CURRENT RESEARCH IN LINGUISTICS Secretariat: Doctoral Program in Linguistics, Postgraduate, Universitas Sebelas Maret Jl. Ir. Sutami 36A Kentingan, Surakarta 57126, Telp/Fax (0271) 632450 Psw 377 Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] Website: s3linguistik.pasca.uns.ac.id Nomor : 05/PRASASTI/III/S3LG/2016 s3s3linguistik.pasca.uns.ac.idLampiran : 1 (satu) eksemplar Hal : Pengumuman abstrak PRASASTI III Yth. Bapak/Ibu Penulis Makalah Seminar Internasional PRASASTI III Dengan hormat, Bersama ini kami sampaikan bahwa abstrak Bapak/Ibu dinyatakan diterima untuk dapat disajikan/ dipresentasikan pada Seminar Internasional PRASASTI III yang diselenggarakan oleh Program Studi S3 Linguistik Pascasarjana Universitas Sebelas Maret. Sehubungan dengan hal tersebut, dimohon Bapak/Ibu memperhatikan poin-poin sebagai berikut. 1. Mengirimkan abstrak beserta fullpaper sesuai dengan ketentuan melalui email [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) dengan subjek dan nama file Nama_FullPaperPrasasti3 dalam format doc. atau rtf (jangan mengirim pdf) paling lambat pada tanggal 8 Juli 2016. 2. Melakukan pembayaran sesuai dengan ketentuan. 3. Mengisi formulir pendaftaran melalui yang formulirnya akan kami kirimkan melalui email dan/atau melalui website s3linguistik.pasca.uns.ac.id 4. Mengirim bukti pembayaran melalui email [email protected] (cc: [email protected]) dengan subjek Pembayaran_Nama_NoHP 5. Bukti transfer mohon disimpan dan dibawa pada saat seminar (2-3 Agustus 2016) Berikut kami lampirkan daftar nama penulis abstrak yang dinyatakan lolos seleksi untuk menuliskan fullpaper. Demikian pemberitahuan dari kami. Kami sampaikan terima kasih atas kerjasama Bapak/Ibu. Kami mengharapkan kehadiran Bapak/Ibu pada acara seminar tersebut tanggal 2 – 3 Agustus 2016, di Syariah Hotel Solo. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This Chapter Presents Five Subtopics

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This chapter presents five subtopics, namely; research background, research questions, research objective, research limitation and research significance. 1.1 Research Background Language is essentially a speech of the mind and feeling of human beings on a regular basis, which uses sound as a tool (Ministry of National Education, 2005: 3). Language is a structure and meaning that is free from its users, as a sign that concludes a goal (HarunRasyid, Mansyur&Suratno 2009: 126). Language is a particular kind of system that is used to transfer the information and it is an encoding and decoding activity in order to get information (Seken, 1992). The number of languages in the world varies between (6,000-7,000) languages. However, the right estimates depend on arbitrary changes between various languages and dialects. Natural language is sign language but each language can be encoded into a second medium using audio, visual, or touch stimuli, for example, in the form of graphics, braille, or whistles. This is because human language is an independent modality. All languages depend on a symbiotic process to connect signals with certain meanings. In Indonesia there are many very beautiful cities and many tribes that have different languages and are very interesting to learn. One of the cities to be studied is Banyuwangi Regency. Banyuwangi Regency is a district of East Java province in Indonesia. This district is located in the easternmost part of Java Island. Banyuwangi is separated by the Bali Strait from Bali. Banyuwangi City is the administrative capital. The name Banyuwangi is the Javanese language for "fragrant water", which is connected with Javanese folklore on the Tanjung. -

MEDAN BAHASA JURNAL ILMIAH KEBAHASAAN Volume 6, No

ISSN 1907—1787 MEDAN BAHASA JURNAL ILMIAH KEBAHASAAN Volume 6, No. 2, Edisi Desember 2012 Penanggung Jawab: Amir Mahmud • Pemimpin Redaksi: Awaludin Rusiandi • Sekretaris Redaksi: Ai Siti Rohmah • Penyunting Ahli: Achmad Effendi Kadarisman (Etnolinguistik/Universitas Negeri Malang), Kisyani-Laksono (Dialektologi/Universitas Negeri Surabaya) • Penyunting Pelaksana: Anang Santosa, Khoiru Ummatin, Arif Izzak, Hero Patrianto • Mitra Bestari: Tri Mastoyo Jati K. (Tata Bahasa/Universitas Gadjah Mada), Ni Ketut Mirahayuni (Analisis Wacana/Universitas 17 Agustus 1945 Surabaya) • Juru Atak: Punjul Sungkari • Distribusi: Rahmidi Penerbit Balai Bahasa Provinsi Jawa Timur Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Alamat Redaksi Balai Bahasa Provinsi Jawa Timur Jalan Siwalanpanji II/1, Buduran, Sidoarjo 61252 Telepon/Faksimile (031) 8051752 Pos-el: [email protected] Jurnal Medan Bahasa terbit dua kali setahun pada bulan Juni dan Desember. Jurnal ini berisi tulisan ilmiah berupa hasil penelitian, kajian dan aplikasi teori, gagasan konseptual, serta resensi buku dengan wilayah kajian kebahasaan. Redaksi jurnal Medan Bahasa mengundang para pakar, dosen, guru, dan peneliti bahasa untuk menulis artikel ilmiah yang berkaitan dengan masalah kebahasaan. Naskah yang masuk disunting secara anonim oleh penyunting ahli. Untuk keseragaman format, penyunting pelaksana berhak melakukan perubahan tanpa mengubah isi tulisan. ISSN 1907—1787 PRAKATA Jurnal Medan Bahasa Volume 6, Edisi Desember 2012, menyajikan sepuluh artikel hasil penelitian dan kajian. Artikel-artikel yang dimuat dalam edisi ini didominasi oleh penelitian atau kajian terhadap bahasa daerah; tujuh artikel meneliti atau mengkaji bahasa daerah, dua artikel melibatkan bahasa asing, dan satu artikel mengkaji penggunaan bahasa Indonesia di ranah elektronik. Artikel pertama berjudul “Derivasi Transposisional pada Kategori Verba Denominal dalam Bahasa Osing” ditulis oleh Asrumi. -

Looking Into the Language Status of Osing with a Contrastive Analysis of the Basic Vocabulary of Osing and Malang Javanese

Parole: Journal of Linguistics and Education, 10 (2), 2020, 87-96 Available online at: https://ejournal.undip.ac.id/index.php/parole Looking into the Language Status of Osing with a Contrastive Analysis of the Basic Vocabulary of Osing and Malang Javanese Ika Nurhayani*, Hamamah Hamamah, Dwi I. N. A. Mardiana, Ressi M. Delijar Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO Osing is a language spoken by the majority of people in Banyuwangi, East Java. However, there is obscurity on its status whether it is considered as one of the Javanese dialects or as an independent language originated in Java. Paper type: Some noted that the Osing is another version of Javanese, while the people Research Article living in the Banyuwangi Region regard the Osing as a distinct identity that differentiates it from the rest of the Javanese speaking regions in Central and Article history: East Java. Hence, this research aims to provide linguistic evidence on the Received 04/02/2020 lexical differences between the Osing and Malang Javanese. The research is Revised 22/06/2020 significant because there is no previous research that provides linguistic Published 26/10/2020 evidence on the differences between the Osing and other Javanese dialects. Data of this study was obtained through eliciting the production of the basic Keywords: vocabulary of the Osing and Malang Javanese speakers. The findings of the Language Status Osing research provide evidence to the observation of previous linguists in that the Contrastive Analysis Osing is not a linguistically separate language of Javanese. Malang Javanese 1. Introduction Osing is a language spoken by 300.000 people in Banyuwangi (Eberhard, David M., Gary F. -

Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Ban on TAPS in Banyuwangi Indonesia (1

Research paper Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054443 on 19 October 2018. Downloaded from Mixed-methods evaluation of a ban on tobacco advertising and promotion in Banyuwangi District, Indonesia Susy K Sebayang,1 Desak Made Sintha Kurnia Dewi,1 Syifa’ul Lailiyah,2 Abdillah Ahsan3 4 ► Additional material is ABStract to 5.4% by 2019. Most of these children started published online only. To view Introduction Tobacco advertisement bans in Indonesia smoking before they were 16 years old (66.7%) please visit the journal online and smoked cloves cigarettes (68.7%).4 It is not a (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ are rare and seldom evaluated. The recent introduction tobaccocontrol- 2018- 054443). of an outdoor tobacco advertisement (OTA) ban in surprise therefore that there were nearly 2 million Banyuwangi District, East Java, Indonesia provided an cases of tobacco-related diseases and 230 862 tobac- 1Department of Biostatistics opportunity to evaluate such policy. co-related deaths in the country in 2015 alone. It and Population Studies, Faculty Methods Using a mixed-methods approach, we was estimated that due to tobacco use the country of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Banyuwangi, undertook an observational study of OTA in 15 locations bears a total economic loss of US$45.9 billion in 5 Indonesia where such advertising had been prohibited. We also that year. Tobacco advertising in Indonesia is 2Department of Health Policy interviewed a sample of 114 store-owners/storekeepers both creative and aggressive,6 promoting associa- and Administration, Faculty and 131 community members, and conducted indepth tions between smoking and emotional control, and of Public Health, Universitas interviews with government officials and the Public Order using varied themes, such as masculinity, moder- Airlangga, Banyuwangi, 7 Indonesia Agency (POA), the designated enforcement agency. -

153 Natasha Abner (University of Michigan)

Natasha Abner (University of Michigan) LSA40 Carlo Geraci (Ecole Normale Supérieure) Justine Mertz (University of Paris 7, Denis Diderot) Jessica Lettieri (Università degli studi di Torino) Shi Yu (Ecole Normale Supérieure) A handy approach to sign language relatedness We use coded phonetic features and quantitative methods to probe potential historical relationships among 24 sign languages. Lisa Abney (Northwestern State University of Louisiana) ANS16 Naming practices in alcohol and drug recovery centers, adult daycares, and nursing homes/retirement facilities: A continuation of research The construction of drug and alcohol treatment centers, adult daycare centers, and retirement facilities has increased dramatically in the United States in the last thirty years. In this research, eleven categories of names for drug/alcohol treatment facilities have been identified while eight categories have been identified for adult daycare centers. Ten categories have become apparent for nursing homes and assisted living facilities. These naming choices function as euphemisms in many cases, and in others, names reference morphemes which are perceived to reference a higher social class than competitor names. Rafael Abramovitz (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) P8 Itai Bassi (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Relativized Anaphor Agreement Effect The Anaphor Agreement Effect (AAE) is a generalization that anaphors do not trigger phi-agreement covarying with their binders (Rizzi 1990 et. seq.) Based on evidence from Koryak (Chukotko-Kamchan) anaphors, we argue that the AAE should be weakened and be stated as a generalization about person agreement only. We propose a theory of the weakened AAE, which combines a modification of Preminger (2019)'s AnaphP-encapsulation proposal as well as converging evidence from work on the internal syntax of pronouns (Harbour 2016, van Urk 2018). -

Indo 88 0 1255982649 131

Democracy and Patrimonial Politics in Local Indonesia Nankyung Choi Introduction After a decade of political and administrative reform and several rounds of competitive elections, Indonesia, by most accounts, displays a democratic political system. There is little consensus on the character of the country's democracy, however. Optimists have called Indonesia one of Southeast Asia's most vibrant democracies, a claim that, upon a moment's reflection, says remarkably little. It is no coincidence that many sunny accounts of Indonesia's politics are fixated on Jakarta and national politics, providing a decidedly thin understanding of the actual state of Indonesia's political institutions. By contrast, analysts of the country's local politics, though cognizant and appreciative of the country's significant democratic gains, have presented evidence that questions the quality of the country's democratic institutions.1 These more critical accounts show that, despite the presence of elections, competitive political parties, and a relatively free press, Indonesia's politics are frequently determined by such non-democratic mechanisms as corruption, intimidation, and clientelism. One common assumption that both optimistic and realistic accounts of 1 See, for instance, Edward Aspinall and Greg Fealy, eds., Local Power and Politics in Indonesia: Decentralization and Democratisation (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2003); Henk Schulte Nordholt, "Renegotiating Boundaries: Access, Agency, and Identity in Post-Soeharto Indonesia," Bijdragen -

Ethnography of Communicative Codes in East Java

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series D - No. 39. ETHNOGRAPHY OF COMMUNICATIVE CODES IN EAST JAVA by Soeseno Kartomihardjo (MATERIALS IN LANGUAGES OF INDONESIA No.8.) W.A.L. Stokhof, Series Editor. Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Kartomihardjo, S. Ethnography of communicative codes in East Java. D-39, xii + 223 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1981. DOI:10.15144/PL-D39.cover ©1981 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A - Occasional Papers SERIES B - Monographs SERIES C - Books SERIES D - Special Publications EDITOR: S.A. Wurm ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W. Bender John Lynch University of Hawaii University of Papua New Guinea David Bradley K.A. McElhanon . University of Melbourne University of Texas A. Capell H.P. McKaughan University of Sydney University of Hawaii S.H. Elbert P. MOhlhiiusler University of Hawaii Linacre College, Oxford K.J. Franklin G.N. O'Grady Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Victoria, B.C. W.W. Glover A.K. Pawley Sum mer Institute of Linguistics University of Auckland G.W. Grace K.L. Pike University of Michigan; University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics M.A.K. Halliday E.C. Polome University of Sydney University of Texas A. Healey Gillian Sank off Sum mer Institute of Linguistics University of Pennsylvania L.A. -

Revealing the Linguistic Features Used in Mantra Pengasihan (The Spell of Affection) in Banyuwangi

available at http://ejournal.unp.ac.id/index.php/humanus/index PRINTED ISSN 1410-8062 ONLINE ISSN 2928-3936 Vol. 19 No. 2, 2020 Published by Pusat Kajian Humaniora (Center for Humanities Studies) FBS Universitas Negeri Padang, Indonesia Page 230-242 Revealing the Linguistic Features Used in Mantra Pengasihan (The Spell of Affection) in Banyuwangi Mengungkap Fitur Linguistik dalam Mantra Pengasihan (Mantra Kasih Sayang) di Banyuwangi Sukarno, Wisasongko, & Imam Basuki English Department, FIB Universitas Jember Email: [email protected] Submitted: 2020-07-08 Published: 2020-11-18 DOI: 10.24036/humanus.v19i2.109117 Accepted: 2020-11-14 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.24036/humanus.v19i2.109117 Abstract As a country with full of cultural diversity, Indonesia has various cultures comprising knowledge, belief, art, law, moral, custom, and habit possessed by human as a member of a community. One of the cultural forms in Indonesia is mantra which is still maintained up to the current time and is still practiced by the community in many different places for many different purposes. One of the existing mantras is mantra pengasihan (the spell of affection). The aim of this study is to reveal the role of linguistic features used in mantra pengasihan (MP), especially Sabuk Mangir. The data were collected by deeply interviewing some Subjects (shamans/dukun/pawang or the mantra spellers) and the Object (the target persons) in Glagah and Licin Subdistricts, Banyuwangi. Having been collected, the data were analyzed by content analysis approach to find the types of languages, the narrative elements, the sentence patterns, and the figurative languages used in MP. -

1 Linguistic Analysis on Javanese Language

LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS ON JAVANESE LANGUAGE SELOGUDIG-AN DIALECT IN SELOGUDIG, PAJARAKAN, PROBOLINGGO Lusi Nur Aini (Corresponding Author) Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of Language and Literature Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jln. S. Supriadi No. 48 Malang 65148, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 82-301-732-015 E-mail: [email protected] Arining Wibowo Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of Language and Literature Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jln. S. Supriadi No. 48 Malang 65148, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 85-646-389-803 E-mail: [email protected] Maria G. Sriningsih Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of Language and Literature Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jln. S. Supriadi No. 48 Malang 65148, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 85-933-033-177 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Linguistic analysis is an analysis of language study which include language form, language meaning, and language in context. Study of linguistic can learn the kind of approaches in language. For example, grammar, language and culture, like the study of cultural discourses and dialects is the domain of sociolinguistics, which looks at the relation between linguistic variation and social structures. Language is one of human characteristics because people living with language. Indonesia is well known of one thousand islands country and as 1000 languages country. So, in Indonesia, there are many vernaculars from each ethnicity in every region of Indonesia. Javanese language has the most speakers of the existing another language speakers. As a language that has a lot of speakers, Javanese language has a lot of kinds or dialect forms as a result of the space and time process. -

6 Days in Bali, Banyuwangi, Mount Bromo and Surabaya, Indonesia

Experience Bali’s nature and calture and enjoy Banyuwangi, in the east-most city on Java, is the gateway to your explorations to Ijen plateau or known as 'Kawah Ijen', which is highly recommended to mountain buffs and hikers. The Plateau was at one time a huge active crater, 134 sq km in area. The vent is a source of sulfur and collectors work here, making the trek up to the crater and down to the lake every day. Experiencing a blue fire in the early morning is the main highlight at this crater. Combining with an early morning sunrise journey at Mount Bromo make the journey is a truly exciting. 6 days in Bali, Banyuwangi, D1 ARRIVE BALI – TANAH LOT (2N) Dinner Upon arrival, Met your Local Guide and travel north-west through bustling kuta and Mount Bromo and Surabaya, Seminyak to Tanah Lot - the site of the pilgrimage holy sea temple- Pura Luhur Indonesia Tanah Lot,an ancient temple dating back to the 12th century. An orange tanged TOUR CODE: MY0119BIB06SJ sunset could beenjoyed here in the late afternoon. After dinner you are transferred Sales period: 10Aug-31Mar 2019 to your hotel for check-in . Balance the day at leisure Travel Period: 01Sep – 31Mar 2019 Grill Seafood Dinner at AROMA Cafe in Jimbaran bay TRAVEL STYLE: Soft Adevture & leisure AGES: 12 – 55yrs old D2 UBUD – TAMPAKSIRING – KINTAMANI – TEGALLALANG Not reccomended for kid below 12yrs old Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner SERVICE LEVEL: Standard SIC Touring Travel eastward to Kintamani, overlooking the active volcano of Mt. Batur. Along • Carefully selected comfortable the way you’ll be facinated with Balinese Countryside, Villages , and Temple.