Ethnography of Communicative Codes in East Java

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 14.4, Phags-Pa

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

D 328 the Bioregional Principal at Banyuwangi Region Development

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, November 26-28, 2019 The Bioregional Principal at Banyuwangi Region Development in the Context of Behavior Maintenance Ratna Darmiwati Catholic University of Darma Cendika, Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract The tourism, natural resources, local culture and Industries with the environment are the backbone of the government's foreign development in the region exchange. The sustainable development without the environment damaging that all activities are recommended, so that between the nature and humans can be worked simultaneously. The purpose of study is maintaining the natural conditions as they are and not to be undermined by irresponsible actions. All of them are facilitated by the government, while maintaining the Osing culture community and expanding the region and make it more widely known. The maintenance of the natural existing resources should be as good as possible, so that it can be passed on future generations in well condition. All of the resources, can be redeveloped in future. The research method used qualitative-descriptive-explorative method which are sorting the datas object. The activities should have involved and relevant with the stakeholders such as the local government, the community leaders or non-governmental organizations and the broader community. The reciprocal relationships between human beings as residents and the environment are occurred as their daily life. Their life will become peaceful when the nature is domesticated. The nature will not be tampered, but arranged in form of human beings that can be moved safely and comfortably. Keywords: The Culture, Industry, Natural Resources, Tourism. -

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

The Word Formation of Panyandra in Javanese Wedding

The Word Formation of Panyandra in Javanese Wedding Rahutami Rahutami and Ari Wibowo Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra Indonesia, Fakultas Bahasa dan Sastra, Universitas Kanjuruhan Malang, Jl. S. Supriyadi 48 Malang 65148, Indonesia [email protected] Keywords: Popular forms, literary forms, panyandra. Abstract: This study aims to describe the form of speech in the Javanese wedding ceremony. For this purpose, a descriptive kualitatif methode with 'direct element' analysis of the word panyandra is used. The results show that there are popular forms of words and literary words. Vocabulary can be invented form and a basic form. The popular form is meant to explain to the listener, while the literary form serves to create the atmosphere the sacredness of Javanese culture. The sacredness was built with the use of the Old Javanese affixes. Panyandra in Malang shows differences with panyandra used in other areas, especially Surakarta and Jogjakarta style. 1 INTRODUCTION The panyadra are the words used in various Javanese cultural events. These words serve to describe events by using a form that has similarities Every nation has a unique culture. Each ethnic has a ritual in life, for example in a wedding ceremony or parallels (pepindhan). Panyandra can be distinguished by cultural events, such as birth, death, (Rohman & Ismail, 2013; Safarova, 2014). A or marriage. These terms adopt many of the ancient wedding ceremony is a sacred event that has an important function in the life of the community, and Javanese vocabulary and Sanskrit words. It is intended to give a formal, religious, and artistic each wedding procession shows a way of thinking impression. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0--Online Edition

This PDF file is an excerpt from The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0, issued by the Unicode Consor- tium and published by Addison-Wesley. The material has been modified slightly for this online edi- tion, however the PDF files have not been modified to reflect the corrections found on the Updates and Errata page (http://www.unicode.org/errata/). For information on more recent versions of the standard, see http://www.unicode.org/standard/versions/enumeratedversions.html. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The Unicode® Consortium is a registered trademark, and Unicode™ is a trademark of Unicode, Inc. The Unicode logo is a trademark of Unicode, Inc., and may be registered in some jurisdictions. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. -

Old Javanese Legal Traditions in Pre-Colonial Bali

HELEN CREESE Old Javanese legal traditions in pre-colonial Bali Law codes with their origins in Indic-influenced Old Javanese knowledge sys- tems comprise an important genre in the Balinese textual record. Significant numbers of palm-leaf manuscripts, as well as later printed copies in Balinese script and romanized transliteration, are found in the major manuscript col- lections. A general overview of the Old Javanese legal corpus is included in Pigeaud’s four-volume catalogue of Javanese manuscripts, Literature of Java, under the heading ‘Juridical Literature’ (Pigeaud 1967:304-14, 1980:43), but detailed studies remain the exception. In spite of the considerable number of different legal treatises extant, and the insights they provide into pre-colonial judicial practices and forms of government, there have only been a handful of studies of Old Javanese and Balinese legal texts. A succession of nineteenth-century European visitors, ethnographers and administrators, notably Thomas Stamford Raffles (1817), John Crawfurd (1820), H.N. van den Broek (1854), Pierre Dubois,1 R. Friederich (1959), P.L. van Bloemen Waanders (1859), R. van Eck (1878-80) and Julius Jacobs (1883), routinely described legal practices in Bali, but European interest in Balinese legal texts was rarely philological. The first legal text to be published was a Dutch translation, without a word of commentary or explanation, of a section of the Dewadanda (Blokzeijl 1872). Then, in the early twentieth cen- tury, after the establishment of Dutch colonial rule over the entire island in 1908, Balinese (Djilantik and Oka 1909a, 1909b) and later Malay (Djlantik and Schwartz 1918a, 1918b, 1918c) translations of certain law codes were produced at the behest of Dutch officials who maintained that the Balinese priests who were required to administer adat law were unable to understand 1 Pierre Dubois,’Idée de Balie; Brieven over Balie’, [1833-1835], in: KITLV, H 281. -

Introduction to Old Javanese Language and Literature: a Kawi Prose Anthology

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES THE MICHIGAN SERIES IN SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS Editorial Board Alton L. Becker John K. Musgrave George B. Simmons Thomas R. Trautmann, chm. Ann Arbor, Michigan INTRODUCTION TO OLD JAVANESE LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE: A KAWI PROSE ANTHOLOGY Mary S. Zurbuchen Ann Arbor Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan 1976 The Michigan Series in South and Southeast Asian Languages and Linguistics, 3 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-16235 International Standard Book Number: 0-89148-053-6 Copyright 1976 by Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-053-2 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12818-1 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90218-7 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ I made my song a coat Covered with embroideries Out of old mythologies.... "A Coat" W. B. Yeats Languages are more to us than systems of thought transference. They are invisible garments that drape themselves about our spirit and give a predetermined form to all its symbolic expression. When the expression is of unusual significance, we call it literature. "Language and Literature" Edward Sapir Contents Preface IX Pronounciation Guide X Vowel Sandhi xi Illustration of Scripts xii Kawi--an Introduction Language ancf History 1 Language and Its Forms 3 Language and Systems of Meaning 6 The Texts 10 Short Readings 13 Sentences 14 Paragraphs.. -

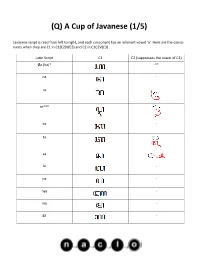

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2. -

Revealing the Linguistic Features Used in Mantra Pengasihan (The Spell of Affection) in Banyuwangi

available at http://ejournal.unp.ac.id/index.php/humanus/index PRINTED ISSN 1410-8062 ONLINE ISSN 2928-3936 Vol. 19 No. 2, 2020 Published by Pusat Kajian Humaniora (Center for Humanities Studies) FBS Universitas Negeri Padang, Indonesia Page 230-242 Revealing the Linguistic Features Used in Mantra Pengasihan (The Spell of Affection) in Banyuwangi Mengungkap Fitur Linguistik dalam Mantra Pengasihan (Mantra Kasih Sayang) di Banyuwangi Sukarno, Wisasongko, & Imam Basuki English Department, FIB Universitas Jember Email: [email protected] Submitted: 2020-07-08 Published: 2020-11-18 DOI: 10.24036/humanus.v19i2.109117 Accepted: 2020-11-14 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.24036/humanus.v19i2.109117 Abstract As a country with full of cultural diversity, Indonesia has various cultures comprising knowledge, belief, art, law, moral, custom, and habit possessed by human as a member of a community. One of the cultural forms in Indonesia is mantra which is still maintained up to the current time and is still practiced by the community in many different places for many different purposes. One of the existing mantras is mantra pengasihan (the spell of affection). The aim of this study is to reveal the role of linguistic features used in mantra pengasihan (MP), especially Sabuk Mangir. The data were collected by deeply interviewing some Subjects (shamans/dukun/pawang or the mantra spellers) and the Object (the target persons) in Glagah and Licin Subdistricts, Banyuwangi. Having been collected, the data were analyzed by content analysis approach to find the types of languages, the narrative elements, the sentence patterns, and the figurative languages used in MP. -

Javanese Language Preservation in the Global Era: Determining Effective Teaching Methods for Elementary School Students Advances

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 www.alls.aiac.org.au Javanese Language Preservation in the Global Era: Determining Effective Teaching Methods for Elementary School Students Lusia Neti Harwati* Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Brawijaya University, Jalan Veteran Malang, East Java, Indonesia Corresponding Author: Lusia Neti Harwati, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Previous studies on Javanese language emphasized more on the use of this local language in Received: March 14, 2018 certain communities and ignored the importance of teaching and learning at an elementary Accepted: May 21, 2018 school level in order to preserve the language. The purpose of this study was to describe the Published: August 31, 2018 lives of the participants, collect and tell stories about their lives, and then write narratives of Volume: 9 Issue: 4 their experiences. The data were gathered through the collection of stories, reporting individual Advance access: July 2018 experiences, and discussing the meaning of those experiences for the participants by proposing a research question: what is the story of the teachers who tried to preserve Javanese language in the global era? A narrative research design, sociolinguistics, and social change as theories Conflicts of interest: None were applied in order to understand teachers’ point of view on globalization and the importance Funding: The research is financed by of preserving Javanese language. Purposeful sampling was used and two teachers were chosen DPP/SPP 2016, Faculty of Cultural as participants. The data gathered were then analyzed through three steps, namely code the Sciences, Brawijaya University data, description, and interpretation. -

Indo 91 0 1302899078 77 1

The M usic of Bedhaya Anduk: A Lost Treasure Rediscovered Noriko Ishida1 Bedhaya is a genre of traditional Javanese court dances performed by nine female dancers accompanied by a gamelan ensemble, the main component of which is a vocal chorus, in a style of gamelan music called bedhayan. The court of the Kasunanan in Surakarta, or Solo, Central Java, has long been famous for its bedhaya. More than thirty bedhaya titles are found in manuscripts of song texts produced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but of the thirty-odd bedhaya for which we have the lyrics, those which have been performed until now are only three: Bedhaya Ketawang, Bedhaya Duradasih, and Bedhaya Pangkur. As for the rest, we have lost either the choreography or the accompanying music, or both, and therefore they cannot be performed properly any more. Bedhaya Anduk, also called Bedhaya Gadhungmlathi, is one of those bedhaya that contemporary musicians have been unable to perform because both its choreography and the accompanying music were lost, but I recently discovered the notation of what seems to be the melody and musical accompaniment of Bedhaya Anduk in one of the notebooks written in 1907 by a Solonese court musician. Alas, I have not yet been able to find any other, independent source to corroborate my conclusion that this is the music of Bedhaya Anduk, but judging from the high artistic status of the musician who notated the piece, and from the lyrics and the melody itself, all of which will be discussed below, it seems safe to say that the notation in question is genuine. -

Paper Title (Use Style: Paper Title)

1st UPI International Conference on Sociology Education (UPI ICSE 2015) Local Wisdom in Constructing Students’ Ecoliteracy Through Ethnopedagogy and Ecopedagogy N. Supriatna The Department of Social Studies Education Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia Bandung, INDONESIA [email protected] Abstract— This paper entails some ideas of how students’ attitude on global product consumption reflects not only their ecological intelligence is constructed through ethnopedagogy and consumptive behavior, but also their delicacy to resist global ecopedagogy within the process of teaching and learning at influence. Consumptive behavior is a negative effect of new schools in Indonesia. This paper is expected to draw provide imperialism supported by capitalism and free market economy some inspiration to high school teachers in the area of social (Harvey, 2013, and Supriatna, 2015). To deal with sciences, such as Social Studies, History, and Sociology, to globalization movement, students need to be empowered by explore and make the best use of local wisdom values in order to implementing ecopedagogical and ethnopedagogical support students’ ecological intelligence. Ethnopedagogy and approaches that make use of local wisdom values in folklore ecopedagogy were utilized during the process as both are for classroom learning activities. considered as forms of educational approaches and practices. Ethnopedagogy specifically refers to a form of educational Numerous tribes in Indonesia have traditions entailing local approaches and practices based on local wisdom. In wisdom. There are many definitions of local wisdom, but ecopedagogy, however, such approaches and practices are not generally it is described as verified consideration, awareness, only specifically based on local wisdom, but also on various action, and belief implemented in the society for many aspects directed to gain understanding, awareness, and life skills generations and used as life basis/principles.