Simon's Town Agreement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Episcopalciiuriimen

EPISCOPALCIIURIIMEN soUru VAFR[CA Room 1005 * 853 Broadway, New York, N . Y. 10003 • Phone : (212) 477-0066 , —For A free Southern Afilcu ' May 1982 MISSIONS MOVEMENTS NAMIBIA 'The U .S. 'overnment has become an agent in South Africa's "holy crusade" against Communism . ' - The Rev Dr Albertus Maasdorp, general secretary of the Council of Churches in Namibia, THE NEW YORK TIMES, 25 April 1982. It was a . mission of frustration and a harsh learning experience . Four Namibian churchmen made a month-long visit to Western nations to express their feelings about the unending, agonizing occupation of their country by the South African regime and the fruitless talks on a Namibian settlement which the .Western Contact Group - the USA, Britain, France ,West Germany and Canada - has staged for five long years . Anglican Bishop James Kauluma, presi- dent of the Council of Churches in Namibia ; Bishop Kleopas Du neni of the Evangelical Luth- eran Ovambokavango Church ; Pastor Albertus Maasdorp, general secretary of the CCN ;, and the, assistant to Bishop D,mmeni, Pastor Absalom Hasheela, were accompanied by a representative of the South African Council of Churches and the general secretary of the All Africa Coun- cil of Oburches which sponsored the trip . They visited France, Sweden, Britain and Canada, end terminated their journey in the United States . It was here that the Namibian pilgrims encountered the steely disregard for Namibian aspirations by functionaries of a major power mapped up in its geopolitical stratagems. They met with Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester .Crocker, whose time is primarily devoted to pursuing the mirage of a Pretorian agreement to the United Nations settlement plan for Namibia . -

Personnel Strategies for the Sandf to 2000 and Beyond

number fourteen THE CRITICAL COMPONENT: PERSONNEL STRATEGIES FOR THE SANDF TO 2000 AND BEYOND by James Higgs THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Established 1934 The Critical Component: Personnel Strategies for the SANDF to 2000 and Beyond James Higgs The Critical Component: Personnel Strategies for the SANDF to 2000 and Beyond James Higgs Director of Studies South African Institute of International Affairs Copyright ©1998 THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Jan Smuts House, Braamfontein, Johannesburg, South Africa Tel: (011) 339-2021; Fax: (011) 339-2154 All rights reserved ISBN: 1-874890-92-7 Report No. 14 SAIIA National Office Bearers Dr Conrad Strauss Gibson Thula • Elisabeth Bradley Brian Hawksworth • Alec Pienaar Dr Greg Mills Abstract This report contains the findings of a research project which examined the way in which the personnel strategies in the South African National Defence Force (SANDF ) are organised. A number of recommendations are made which are aimed at securing efficient, effective and democratically legitimate armed forces for South Africa. Section Four sets out the recommendations in the areas of: a public relations strategy for the SANDF ; the conditions of service which govern employment of personnel; a plan for retaining key personnel; a strategy for the adjustment of pay structures; a review of race representivity plans for the SANDF ; a strategy for reducing internal tension while reinforcing cultural identity and diversity; an overview of the rationalisation and retrenchment plans; observations on the health and fitness of the SANDF personnel; recommendations for increased efficiency in the administrative process and for the review of the current structure of support functions. -

The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 2, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J. N6thling* assisted by Mrs L. 5teyn* The early period for Blacks, Coloureds and Indians were non- existent. It was, however, inevitable that they As long ago as 1700, when the Cape of Good would be resuscitated when war came in 1939. Hope was still a small settlement ruled by the Dutch East India Company, Coloureds were As war establishment tables from this period subject to the same military duties as Euro- indicate, Non-Whites served as separate units in peans. non-combatant roles such as drivers, stretcher- bearers and batmen. However, in some cases It was, however, a foreign war that caused the the official non-combatant edifice could not be establishment of the first Pandour regiment in maintained especially as South Africa's shortage 1781. They comprised a force under white offi- of manpower became more acute. This under- cers that fought against the British prior to the lined the need for better utilization of Non-Whites occupation of the Cape in 1795. Between the in posts listed on the establishment tables of years 1795-1803 the British employed white units and a number of Non-Whites were Coloured soldiers; they became known as the subsequently attached to combat units and they Cape Corps after the second British occupation rendered active service, inter alia in an anti-air- in 1806. During the first period of British rule craft role. -

SA Navy Is Offering Young South African Citizens an Excellent Opportunity to Serve in Uniform Over a Two-Year Period

defence Department: Defence REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA SOUTH AFRICAN NAVY “THE PEOPLES NAVY” MILITARY SKILLS DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM 2021 COMBAT, ENGINEERING, TECHNICAL, SUPPORT Please indicate highest qualification achieved BACKGROUND Graduate ........................................................................................................ MILITARY SKILLS DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM (MSDS) (e.g. National Diploma Human Resource) Matric The SA Navy is offering young South African citizens an excellent opportunity to serve in uniform over a two-year period. The Military Skills Development System MUSTERING (MSDS) is a two-year voluntary service system with the aim of equipping and TECHNICAL SUPPORT developing young South Africans with the necessary skills in order to compete in the open market. ENGINEERING COMBAT Young recruits are required to sign up for a period of two-years, during which Please complete the following Biographical Information: they will receive Military Training and further Functional Training. First Names: ........................................................................................................... All applicants must comply with the following: Surname: ................................................................................................................ - South African Citizen (no dual citizenship). - Have no record of criminal offences. ID Number: ............................................................................................................. - Not be area bound. Tel.(H) ........................................ -

SOUTH AFRICA, the COLONIAL POWERS and 'AFRICAN DEFENCE' by the Same Author

SOUTH AFRICA, THE COLONIAL POWERS AND 'AFRICAN DEFENCE' By the same author ECONOMIC POWER IN ANGLO-SOUTH AFRICAN DIPLOMACY DIPLOMACY AT THE UN (edited with Anthony Jennings) INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: States, Power and Conflict since 1945 THE POLITICS OF THE SOUTH AFRICA RUN: European Shipping and Pretoria RETURN TO THE UN: UN Diplomacy in Regional Conflicts South Africa, the Colonial Powers and'African Defence' The Rise and Fall of the White Entente, 1948-60 G. R. Berridge Readerill Politics University ofLeicester © G. R. Berridge 1992 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1 st edition 1992 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or * transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, london W1T 4lP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by PAlGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PAlGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin's Press llC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers ltd (formerly Macmillan Press ltd). ISBN 978-1-349-39060-1 ISBN 978-0-230-37636-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230376366 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Communautés Atlantiques / Atlantic Communities: Asymétries Et

SOUS LA DIRECTION DE Dorval Brunelle sociologue, Directeur de l’Institut d’Études Internationales de Montréal, UQAM (2012) Communautés Atlantiques / Atlantic Communities. Asymétries et convergences. Un document produit en version numérique par Jean-Marie Tremblay, bénévole, professeur de sociologie au Cégep de Chicoutimi Courriel: [email protected] Site web pédagogique : http://www.uqac.ca/jmt-sociologue/ Dans le cadre de la collection: "Les classiques des sciences sociales" Site web: http://classiques.uqac.ca/ Une collection développée en collaboration avec la Bibliothèque Paul-Émile-Boulet de l'Université du Québec à Chicoutimi Site web: http://bibliotheque.uqac.ca/ Dorval Brunelle (dir.), Communautés Atlantiques / Atlantic Communities… (2012) 2 Politique d'utilisation de la bibliothèque des Classiques Toute reproduction et rediffusion de nos fichiers est interdite, même avec la mention de leur provenance, sans l’autorisation for- melle, écrite, du fondateur des Classiques des sciences sociales, Jean-Marie Tremblay, sociologue. Les fichiers des Classiques des sciences sociales ne peuvent sans autorisation formelle: - être hébergés (en fichier ou page web, en totalité ou en partie) sur un serveur autre que celui des Classiques. - servir de base de travail à un autre fichier modifié ensuite par tout autre moyen (couleur, police, mise en page, extraits, support, etc...), Les fichiers (.html, .doc, .pdf., .rtf, .jpg, .gif) disponibles sur le site Les Classiques des sciences sociales sont la propriété des Classi- ques des sciences sociales, un organisme à but non lucratif com- posé exclusivement de bénévoles. Ils sont disponibles pour une utilisation intellectuelle et personnel- le et, en aucun cas, commerciale. Toute utilisation à des fins com- merciales des fichiers sur ce site est strictement interdite et toute rediffusion est également strictement interdite. -

HMS Drake, Church Bay, Rathlin Island

Wessex Archaeology HMS Drake, Church Bay, Rathlin Island Undesignated Site Assessment Ref: 53111.02r-2 December 2006 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SERVICES IN RELATION TO THE PROTECTION OF WRECKS ACT (1973) HMS DRAKE, CHURCH BAY, RATHLIN ISLAND UNDESIGNATED SITE ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park Salisbury Wiltshire SP4 6EB Prepared for: Environment and Heritage Service Built Heritage Directorate Waterman House 5-33 Hill St Belfast BT1 2LA December 2006 Ref: 53111.02r-2 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2006 Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No.287786 HMS Drake: Undesignated Site Assessment Wessex Archaeology 53111.02r-2 HMS DRAKE, CHURCH BAY, RATHLIN ISLAND UNDESIGNATED SITE ASSESSMENT Ref.: 53111.02r-2 Summary Wessex Archaeology was commissioned by Environment and Heritage Service: Built Heritage Directorate, to undertake an Undesignated Site Assessment of the wreck of HMS Drake. The site is located in Church Bay, Rathlin Island, Northern Ireland, at latitude 55º 17.1500′ N, longitude 06° 12.4036′ W (WGS 84). The work was undertaken as part of the Contract for Archaeological Services in Relation to the Protection of Wrecks Act (1973). Work was conducted in accordance with a brief that required WA to locate archaeological material, provide an accurate location for the wreck, determine the extent of the seabed remains, identify and characterise the main elements of the site and assess the remains against the non-statutory criteria for designation. Diving operations took place between 28th July and 5th August 2006. In addition to the diver assessment a limited desk-based assessment has been undertaken in order to assist with the interpretation and reporting of the wreck. -

A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa

A SURVEF YO RACE RELATIONS SOUTN I H AFRICA IQ15 Compiley b d MURIEL HORRELL TONY HODGSON Research staff South African Institut f Raco e e Relations ISBN 0 86982 119 9 SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS P.O. BOX 97 JOHANNESBURG JANUARY 1976 k POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS THE WHITE POPULATION GROUP NATIONAL PARTY Durin e yeath g r under review, South Afric s inevitablha a y ; become increasingly concerned and involved with events in the neighbouring countrie f Rhodesiao s , Mozambique d Angolaan , . The Prime . VorsterJ Minister . B s pledge . ha , Mr , d himseld an f . 'his governmen o strivt t r peacefo e , co-operation, progressd an , • developmen Southern i t n Afric d Afric a an wholea s a a n doinI . g so, he has made new and highly significant contacts with Zambia, Tanzania, Botswana d certaian , n other African states, .besides 'Overseas countries. : Speaking in the House of Assembly on 7 February1 Mr. Vorster said, "I thinlc a better understanding of South Africa has developed Africn i worlde i d th n. Ther .. aan s bee ha ea nclea r acceptance f Africa"o e ar ,tha e . w tHowever s notea , d late n thii r s Survey, line attitudeStateU OA a numbeSouto t sf e o sth hf o rAfric a have •hardened. ? As described in the chapter on South West Africa, Mr. Vorslcr ; ,has mad t i cleae r that this territory wile granteb l d complete L Independence as soon as possible, but that it will be for the people r Swapono N o e territort U , th e f •o th yr fo concerned t no d an , determine their future for f governmentmo . -

NAVAL FORCES USING THORDON SEAWATER LUBRICATED PROPELLER SHAFT BEARINGS September 7, 2021

NAVAL AND COAST GUARD REFERENCES NAVAL FORCES USING THORDON SEAWATER LUBRICATED PROPELLER SHAFT BEARINGS September 7, 2021 ZERO POLLUTION | HIGH PERFORMANCE | BEARING & SEAL SYSTEMS RECENT ORDERS Algerian National Navy 4 Patrol Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 Argentine Navy 3 Gowind Class Offshore Patrol Ships Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2022-2027 Royal Australian Navy 12 Arafura Class Offshore Patrol Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2027 Royal Australian Navy 2 Supply Class Auxiliary Oiler Replenishment (AOR) Ships Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 Government of Australia 1 Research Survey Icebreaker Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 COMPAC SXL Seawater lubricated propeller Seawater lubricated propeller shaft shaft bearings for blue water bearings & grease free rudder bearings LEGEND 2 | THORDON Seawater Lubricated Propeller Shaft Bearings RECENT ORDERS Canadian Coast Guard 1 Fishery Research Ship Thordon SXL Bearings 2020 Canadian Navy 6 Harry DeWolf Class Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS) Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020-2022 Egyptian Navy 4 MEKO A-200 Frigates Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2024 French Navy 4 Bâtiments Ravitailleurs de Force (BRF) – Replenishment Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2027 French Navy 1 Classe La Confiance Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 French Navy 1 Socarenam 53 Custom Patrol Vessel Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2019 THORDON Seawater Lubricated Propeller Shaft Bearings | 3 RECENT ORDERS German Navy 4 F125 Baden-Württemberg Class Frigates Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2019-2021 German Navy 5 K130 -

Britain and I South Africa

BRITAIN AND I by SOUTH AFRICA JOHN GOLLAN (General Secretary. Communist Party of Great Britain) F ol~owing a request by the editorial board of THE AFRICAN COMMUNIST lor the views of the Communist Party of Great Britain concerning Britain's relations with the Republic oj South Africa and with the High Commission Territories. the following statement of policy oj the Communist Party of Great Britain has been made by its General Secretary, lohn Gallon. THE SITUATION IN South Africa is rapidly reaching crisis point. The hated Verwoerd Government is piling repression on repression, deter mined to shut down every possibility of protest or criticism of the monstrous system of apartheid. and every demand of the people for democratic rights and for an end to the nightmare of racial dis crimination and fascist tyranny. The only answer to this terror will be the justified revolt of the people of South Africa. The recent historic conference of African heads of state at Addis Ababa shows that Africa is no longer prepared to tolerate the foul blot of apartheid on its soil. The 218 million people of independent· Africa and the 48 million still under European domination have spoken-and now they are preparing to act. It is time for the British people to act, too. The people of Britain have a deep hatred for the whole rotten system of apartheid, a feeling that was sharply manifested at the time of the Sharpeville massacre three years ago, and has since been expressed in the many resolutions ofprotest adopted by numerous progressive organisations in Britain, by the consumer boycott, by numerous meetings and demonstrations, and by the campaign now developing to stop the shipment of arms to Verwoerd. -

South West Africa

South West Africa: travesty of trust; the expert papers and findings of the International Conference on South West Africa, Oxford, 23-26 March 1966, with a postscript by Iain MacGibbon on the 1966 judgement of the International Court of Justice http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10032 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org South West Africa: travesty of trust; the expert papers and findings of the International Conference on South West Africa, Oxford, 23-26 March 1966, with a postscript by Iain MacGibbon on the 1966 judgement of the International Court of Justice Author/Creator Segal, Ronald (editor); First, Ruth (editor) Date 1967 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Namibia Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. -

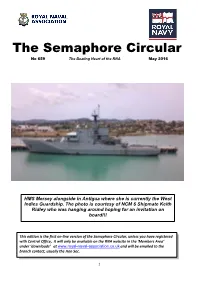

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General