Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume II: Chile, Greece, Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa's Defence Industry: a Template for Middle Powers?

UNIVERSITYOFVIRGINIALIBRARY X006 128285 trategic & Defence Studies Centre WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY University of Virginia Libraries SDSC Working Papers Series Editor: Helen Hookey Published and distributed by: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Tel: 02 62438555 Fax: 02 624808 16 WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds National Library of Australia Cataloguirtg-in-Publication entry Mills, Greg. South Africa's defence industry : a template for middle powers? ISBN 0 7315 5409 4. 1. Weapons industry - South Africa. 2. South Africa - Defenses. I. Edmonds, Martin, 1939- . II. Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. III. Title. 338.4735580968 AL.D U W^7 no. 1$8 AUTHORS Dr Greg Mills and Dr Martin Edmonds are respectively the National Director of the South African Institute of Interna tional Affairs (SAIIA) based at Wits University, Johannesburg, South Africa, and Director: Centre for Defence and Interna tional Security Studies, Lancaster University in the UK. South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? 1 Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds Introduction The South African arms industry employs today around half of its peak of 120,000 in the 1980s. A number of major South African defence producers have been bought out by Western-based companies, while a pending priva tisation process could see the sale of the 'Big Five'2 of the South African industry. This much might be expected of a sector that has its contemporary origins in the apartheid period of enforced isolation and self-sufficiency. -

The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: an Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes

Comment The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: An Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes Raymond Paretzkyt Introduction With reports of violence and unrest in the Republic of South Africa a daily feature in American newspapers, public attention in the United States has increasingly focused on a variety of American efforts to bring an end to apartheid.. Little discussed in the ongoing debate over imposi- tion of new measures is the sanction that the United States has main- tained for the past twenty-three years: the South African arms embargo. How effective has this sanction been in denying South Africa access to items with military utility? Are there ways to strengthen the arms em- bargo so that it achieves greater success? An evaluation of the embargo is complicated by the fact that there is no one place in which the laws implementing it can be found. Rather, the relevant regulations have been incorporated into the existing, com- plex scheme of U.S. trade law. This article offers a complete account of the laws and regulations implementing the embargo, analyzes the defects in the regulatory scheme, and recommends ways to strengthen the em- bargo. The first part outlines the background of the imposition of the embargo, while the next three parts examine the regulations that govern American exports to South Africa and explore the loopholes in these reg- ulations that hinder their effectiveness. Part II discusses items on the t J.D. Candidate, Yale University. 1. Congress recently imposed various sanctions on South Africa. See Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, Pub. -

Personnel Strategies for the Sandf to 2000 and Beyond

number fourteen THE CRITICAL COMPONENT: PERSONNEL STRATEGIES FOR THE SANDF TO 2000 AND BEYOND by James Higgs THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Established 1934 The Critical Component: Personnel Strategies for the SANDF to 2000 and Beyond James Higgs The Critical Component: Personnel Strategies for the SANDF to 2000 and Beyond James Higgs Director of Studies South African Institute of International Affairs Copyright ©1998 THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Jan Smuts House, Braamfontein, Johannesburg, South Africa Tel: (011) 339-2021; Fax: (011) 339-2154 All rights reserved ISBN: 1-874890-92-7 Report No. 14 SAIIA National Office Bearers Dr Conrad Strauss Gibson Thula • Elisabeth Bradley Brian Hawksworth • Alec Pienaar Dr Greg Mills Abstract This report contains the findings of a research project which examined the way in which the personnel strategies in the South African National Defence Force (SANDF ) are organised. A number of recommendations are made which are aimed at securing efficient, effective and democratically legitimate armed forces for South Africa. Section Four sets out the recommendations in the areas of: a public relations strategy for the SANDF ; the conditions of service which govern employment of personnel; a plan for retaining key personnel; a strategy for the adjustment of pay structures; a review of race representivity plans for the SANDF ; a strategy for reducing internal tension while reinforcing cultural identity and diversity; an overview of the rationalisation and retrenchment plans; observations on the health and fitness of the SANDF personnel; recommendations for increased efficiency in the administrative process and for the review of the current structure of support functions. -

The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 2, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J. N6thling* assisted by Mrs L. 5teyn* The early period for Blacks, Coloureds and Indians were non- existent. It was, however, inevitable that they As long ago as 1700, when the Cape of Good would be resuscitated when war came in 1939. Hope was still a small settlement ruled by the Dutch East India Company, Coloureds were As war establishment tables from this period subject to the same military duties as Euro- indicate, Non-Whites served as separate units in peans. non-combatant roles such as drivers, stretcher- bearers and batmen. However, in some cases It was, however, a foreign war that caused the the official non-combatant edifice could not be establishment of the first Pandour regiment in maintained especially as South Africa's shortage 1781. They comprised a force under white offi- of manpower became more acute. This under- cers that fought against the British prior to the lined the need for better utilization of Non-Whites occupation of the Cape in 1795. Between the in posts listed on the establishment tables of years 1795-1803 the British employed white units and a number of Non-Whites were Coloured soldiers; they became known as the subsequently attached to combat units and they Cape Corps after the second British occupation rendered active service, inter alia in an anti-air- in 1806. During the first period of British rule craft role. -

SA Navy Is Offering Young South African Citizens an Excellent Opportunity to Serve in Uniform Over a Two-Year Period

defence Department: Defence REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA SOUTH AFRICAN NAVY “THE PEOPLES NAVY” MILITARY SKILLS DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM 2021 COMBAT, ENGINEERING, TECHNICAL, SUPPORT Please indicate highest qualification achieved BACKGROUND Graduate ........................................................................................................ MILITARY SKILLS DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM (MSDS) (e.g. National Diploma Human Resource) Matric The SA Navy is offering young South African citizens an excellent opportunity to serve in uniform over a two-year period. The Military Skills Development System MUSTERING (MSDS) is a two-year voluntary service system with the aim of equipping and TECHNICAL SUPPORT developing young South Africans with the necessary skills in order to compete in the open market. ENGINEERING COMBAT Young recruits are required to sign up for a period of two-years, during which Please complete the following Biographical Information: they will receive Military Training and further Functional Training. First Names: ........................................................................................................... All applicants must comply with the following: Surname: ................................................................................................................ - South African Citizen (no dual citizenship). - Have no record of criminal offences. ID Number: ............................................................................................................. - Not be area bound. Tel.(H) ........................................ -

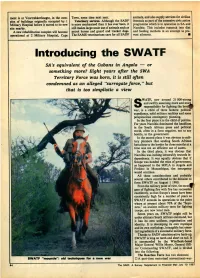

Introducing the SWATF

ment is at Voortrekkerhoogte, in the com Town, some time next year. animals, and also supply services for civilian plex of buildings originally occupied by 1 Veterinary services. Although the SADF livestock as part of the extensive civic action Military Hospital before it moved to its new is more mechanised than it has ever been, it programme which is in operation in SA and site nearby. still makes large-scale use of animals such as Namibia. This includes research into diet A new rehabilitation complex will become patrol horses and guard and tracker dogs. and feeding methods in an attempt to pre operational at 2 Military Hospital, Cape The SAMS veterinarians care for all SADF vent ailments. ■ Introducing the SWATF SA’s equivalent of the Cubans in Angola — or something more? Eight years after the SWA Territory Force was born, it is still often condemned as an alleged "surrogate force," but that is too simplistic a view WATF, now around 21 000-strong and swiftly assuming more and more S responsibility for fighting the bord(^ war, is a child of three fathers: political expediency, solid military realities and some perspicacious contingency planning. In the first place it is the child of politics. For years Namibia dominated the headlines in the South African press and political world, often in a form negative, not to say hostile, to the government. In the second place it was obvious to mili tary planners that sending South African battalions to the border for three months at a time was not an efficient use of assets. -

The Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Stephen Burgess and Helen Purkitt US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE ROLLBACK OF SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE PROGRAM by Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt April 2001 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm . Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Authors ............................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................v Chronology ................................................................................................vii I. Introduction .............................................................................................1 II. The Origins of the Chemical and Biological Warfare Program.............3 III. Project Coast, 1981-1993....................................................................17 IV. Rollback of Project Coast, 1988-1994................................................39 -

NAVAL FORCES USING THORDON SEAWATER LUBRICATED PROPELLER SHAFT BEARINGS September 7, 2021

NAVAL AND COAST GUARD REFERENCES NAVAL FORCES USING THORDON SEAWATER LUBRICATED PROPELLER SHAFT BEARINGS September 7, 2021 ZERO POLLUTION | HIGH PERFORMANCE | BEARING & SEAL SYSTEMS RECENT ORDERS Algerian National Navy 4 Patrol Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 Argentine Navy 3 Gowind Class Offshore Patrol Ships Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2022-2027 Royal Australian Navy 12 Arafura Class Offshore Patrol Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2027 Royal Australian Navy 2 Supply Class Auxiliary Oiler Replenishment (AOR) Ships Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 Government of Australia 1 Research Survey Icebreaker Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 COMPAC SXL Seawater lubricated propeller Seawater lubricated propeller shaft shaft bearings for blue water bearings & grease free rudder bearings LEGEND 2 | THORDON Seawater Lubricated Propeller Shaft Bearings RECENT ORDERS Canadian Coast Guard 1 Fishery Research Ship Thordon SXL Bearings 2020 Canadian Navy 6 Harry DeWolf Class Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS) Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020-2022 Egyptian Navy 4 MEKO A-200 Frigates Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2024 French Navy 4 Bâtiments Ravitailleurs de Force (BRF) – Replenishment Vessels Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2021-2027 French Navy 1 Classe La Confiance Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2020 French Navy 1 Socarenam 53 Custom Patrol Vessel Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2019 THORDON Seawater Lubricated Propeller Shaft Bearings | 3 RECENT ORDERS German Navy 4 F125 Baden-Württemberg Class Frigates Thordon COMPAC Bearings 2019-2021 German Navy 5 K130 -

South African Defence Review 2012

CONSULTATIVE DRAFT PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 2 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT FOREWORD BY THE MINISTER Foreword: (L.N. SISULU) MINISTER OF DEFENCE AND MILITARY VETERANS CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 3 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 4 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT FOREWORD BY THE CHAIRPERSON Foreword: (R. MEYER) CHAIRPERSON OF THE DEFENCE REVIEW COMMITTEE CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 5 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 6 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE FOREWORD Minister of Defence Chairperson of the Defence Review Committee LIST OF FIGURES LIST OF ACRONYMS GLOSSARY OF TERMS (TO BE ADDED) 1 THE DEFENCE REVIEW Introduction Why a new Defence Review? What is the Defence Review? The Perennial Defence Dilemma Developing the Future Defence Policy Overarching Defence Principles 2 THE SOUTH AFRICAN STATE “A DEVELOPMENTAL PERSPECTIVE’ Introduction Form of Government and Legal System Political System Economic System Geography and Topography People and Society South Africa as a Democratic Developmental State Poverty Income Inequality Unemployment Education Criminality Defence and the Developmental State 3 THE STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT Introduction Global Security Trends International Relations, Balance of Power and Diplomacy CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 7 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT CHAPTER TITLE PAGE Inter-State Conflict and War Intra-State Conflict Global Competition for Strategic Resources Acts of Terror Weapons of Mass Destruction -

Tom Conrad, AFSC/NARMIC Tel

AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE 1501 Cherry Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 June 13, 1986 MEMORANDUM From: Tom Conrad, AFSC/NARMIC Tel. (215) 241-7004 . , Re: U.S. rugh-Tech Sales to South Afri.ca The United States is South Africa's top supplier of high-tech equipment. The United Nations arms embargo notwithstanding, U.S. companies ship millions of dollars of strategic goods to Pretoria every year ($185 million in computer hardware in 1984 alone; millions more in other high-tech sales). Despite the embargo, which bans shipments of "arms and related materiel," the U.S. government licenses the commercial export of a vast array of sensitive technology to Pretoria, including computers, electronics, electrooptics and communications equipment. Such shi ments should be sto ed to insure U.S. com liance with the United Nations arms embar o. T scan e one by strengt en lIg H.R. 868 t Ie Ant -Apart eid Act of 1986") which is currently before Congress. H.R. 4868 makes no reference to the arms embargo. While this bill is R step in the right direction, it will not stop U.S. strategic technology from reaching the practicioners of apartheid. How can the Anti-Apartheid Act be strengthened? 1. It should bar exports to South Africa of commodi.ti.es on the Munitions List • .. The Munitions List (Code of Federal Regulations, Title 22, pp. 323-327) identifies 21 categories of technology with explicit military applications. Current export controls continue to permit Munitions List items to be exported to South Africa (the Administration has licensed sales of navigation gear, image intensifiers and data encoding devices ostensibly destined for civilian applications). -

South Africa Missile Chronology

South Africa Missile Chronology 2007-1990 | 1989-1981 | 1980-1969 | 1968-1950 Last update: April 2005 As of May 28, 2009, this chronology is no longer being updated. For current developments, please see the South Africa Missile Overview. This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation 2007-1990 26 April 2007 The state-owned arms manufacturer Denel Group has signed a 1 billion rand (143 million U.S. dollars) deal with Brazil to co-develop a new generation missile. The missile will be the next-generation A-Darter, and air-to-air missile designed to meet future challenges of air combat fighters. The partnership will Brazil will bring "much needed skills, training and technology transfer to the country." Furthermore, future export contracts of another 2 billion rand are expected in the next 15 years. — "S. Africa, Brazil sign missile deal," People's Daily Online, 26 April 2007, english.people.com.cn. -

The Decline of South Africa's Defence Industry

Defense & Security Analysis ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cdan20 The decline of South Africa’s defence industry Ron Matthews & Collin Koh To cite this article: Ron Matthews & Collin Koh (2021): The decline of South Africa’s defence industry, Defense & Security Analysis, DOI: 10.1080/14751798.2021.1961070 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2021.1961070 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 08 Aug 2021. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cdan20 DEFENSE & SECURITY ANALYSIS https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2021.1961070 The decline of South Africa’s defence industry Ron Matthewsa and Collin Kohb aCranfield University, Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, Shrivenham, UK; bS. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The growth of South Africa’s apartheid era defence industry was South Africa; defence propelled by international isolation following the 1984 UN arms industry; arms exports; embargo and revealed military technology deficiencies during the corruption; offset border war. Weapons innovation became an imperative, fostering development of frontier technologies and upgrades of legacy platforms that drove expansion in arms exports. However, this golden era was not to last. The 1994 election of the country’s first democratic government switched resources from military to human security. The resultant defence-industrial stagnation continues to this day, exacerbated by corruption, unethical sales, and government mismanagement.