The Development of South Africa's Arms Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Is the Largest Manufacturer of Defence Equipment in South Africa and Operates in the Military Aerospace and Landward Defence Environment

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY DENEL Denel is a state-owned company (SOC), which is the largest manufacturer of defence equipment in South Africa and operates in the military aerospace and landward defence environment. Denel is an important defence contractor in the domestic market and a key supplier to the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) both as original equipment manufacturer (OEM) and for the overhaul, maintenance, repair, refurbishment and upgrade of equipment in the SANDF’s arsenal. Denel reports to the Minister of Public Enterprises who appoints an independent board of directors to oversee an executive management team, managing the day-to-day operations. The executive management team also manages several business divisions and associated companies, including Denel Aeronautics, Denel Maritime, Pretoria Metal Pressings, Denel Dynamics, Denel Land Systems, Denel Vehicle Systems (Pty) Ltd and Denel Aerostructures SOC Ltd. With the release of the #Guptaleaks in May 2017, the actions and good governance of the board of directors were brought into question, not only because of the Denel-Asia deal, but also because of the relationships between key decision makers and the Gupta family. OUTA explores the capturing of Denel in this submission and provides supporting evidence. Before July 2015, Denel was led by a board of directors chaired by Riaz Saloojee. This board’s direction resulted in a series of profitable years as set out in the second issue of a 2015 Denel- issued communique. Denel had good prospects for its future and an order book of more than R35 billion and the group CFO Fikile Mhlonto was nominated as Public CFO of the year. -

South Africa's Defence Industry: a Template for Middle Powers?

UNIVERSITYOFVIRGINIALIBRARY X006 128285 trategic & Defence Studies Centre WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY University of Virginia Libraries SDSC Working Papers Series Editor: Helen Hookey Published and distributed by: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Tel: 02 62438555 Fax: 02 624808 16 WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds National Library of Australia Cataloguirtg-in-Publication entry Mills, Greg. South Africa's defence industry : a template for middle powers? ISBN 0 7315 5409 4. 1. Weapons industry - South Africa. 2. South Africa - Defenses. I. Edmonds, Martin, 1939- . II. Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. III. Title. 338.4735580968 AL.D U W^7 no. 1$8 AUTHORS Dr Greg Mills and Dr Martin Edmonds are respectively the National Director of the South African Institute of Interna tional Affairs (SAIIA) based at Wits University, Johannesburg, South Africa, and Director: Centre for Defence and Interna tional Security Studies, Lancaster University in the UK. South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? 1 Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds Introduction The South African arms industry employs today around half of its peak of 120,000 in the 1980s. A number of major South African defence producers have been bought out by Western-based companies, while a pending priva tisation process could see the sale of the 'Big Five'2 of the South African industry. This much might be expected of a sector that has its contemporary origins in the apartheid period of enforced isolation and self-sufficiency. -

Quarterly Portfolio Disclosure

Schroders 29/05/2020 ASX Limited Schroders Investment Management Australia Limited ASX Market Announcements Office ABN:22 000 443 274 Exchange Centre Australian Financial Services Licence: 226473 20 Bridge Street Sydney NSW 2000 Level 20 Angel Place 123 Pitt Street Sydney NSW 2000 P: 1300 180 103 E: [email protected] W: www.schroders.com.au/GROW Schroder Real Return Fund (Managed Fund) Quarterly holdings disclosure for quarter ending 31 March 2020 Holdings on a full look through basis as at 31 March 2020 Weight Asset Name (%) 1&1 DRILLISCH AG 0.000% 1011778 BC / NEW RED FIN 4.25 15-MAY-2024 144a (SECURED) 0.002% 1011778 BC UNLIMITED LIABILITY CO 3.875 15-JAN-2028 144a (SECURED) 0.001% 1011778 BC UNLIMITED LIABILITY CO 4.375 15-JAN-2028 144a (SECURED) 0.001% 1011778 BC UNLIMITED LIABILITY CO 5.0 15-OCT-2025 144a (SECURED) 0.004% 1MDB GLOBAL INVESTMENTS LTD 4.4 09-MAR-2023 Reg-S (SENIOR) 0.011% 1ST SOURCE CORP 0.000% 21VIANET GROUP ADR REPRESENTING SI ADR 0.000% 2I RETE GAS SPA 1.608 31-OCT-2027 Reg-S (SENIOR) 0.001% 2I RETE GAS SPA 2.195 11-SEP-2025 Reg-S (SENIOR) 0.001% 2U INC 0.000% 360 SECURITY TECHNOLOGY INC A A 0.000% 360 SECURITY TECHNOLOGY INC A A 0.000% 361 DEGREES INTERNATIONAL LTD 0.000% 3D SYSTEMS CORP 0.000% 3I GROUP PLC 0.002% 3M 0.020% 3M CO 1.625 19-SEP-2021 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 1.75 14-FEB-2023 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 2.0 14-FEB-2025 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 2.0 26-JUN-2022 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 2.25 15-MAR-2023 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 2.75 01-MAR-2022 (SENIOR) 0.001% 3M CO 3.25 14-FEB-2024 (SENIOR) 0.002% -

The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: an Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes

Comment The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: An Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes Raymond Paretzkyt Introduction With reports of violence and unrest in the Republic of South Africa a daily feature in American newspapers, public attention in the United States has increasingly focused on a variety of American efforts to bring an end to apartheid.. Little discussed in the ongoing debate over imposi- tion of new measures is the sanction that the United States has main- tained for the past twenty-three years: the South African arms embargo. How effective has this sanction been in denying South Africa access to items with military utility? Are there ways to strengthen the arms em- bargo so that it achieves greater success? An evaluation of the embargo is complicated by the fact that there is no one place in which the laws implementing it can be found. Rather, the relevant regulations have been incorporated into the existing, com- plex scheme of U.S. trade law. This article offers a complete account of the laws and regulations implementing the embargo, analyzes the defects in the regulatory scheme, and recommends ways to strengthen the em- bargo. The first part outlines the background of the imposition of the embargo, while the next three parts examine the regulations that govern American exports to South Africa and explore the loopholes in these reg- ulations that hinder their effectiveness. Part II discusses items on the t J.D. Candidate, Yale University. 1. Congress recently imposed various sanctions on South Africa. See Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, Pub. -

INDABA 77/13 1 E D I T O R I a L

Das SADOCC-Magazin für das Südliche Afrika 77/13 W A F F E N H A N D E L Südafrikas Sündenfall W I R T S C H A F T Facharbeiter gesucht K O N Z E P T K U N S T Angolas Kiluanji Kia Henda Offenlegung: INDABA wird herausge- geben vom Dokumen ta tions- und Kooperationszentrum Südliches Afrika SADOCC (SADOCC) in Wien (ZVR-Zahl 973735397) und bezweckt die Infor- Das Dokumentations- und Kooperationszentrum Süd- mation und Diskussion über Entwick liches Afrika in Wien setzt sich für eine solidarische -lungen im Südlichen Afrika. Dem Außen-, Wirtschafts- und Entwicklungspolitik gegenüber Vereinsvorstand gehören an: Mag. den Ländern des Südlichen Afrika ein. Bernhard Bouzek, HK Lydia Dyk, Dr. Astrid Esterlus, Johann Gatt ringer, SADOCC: Dr. Ingeborg Grau, MSc Ulrike Dokumentation und Bibliothek in Go melsky, Mag. Robert Konrad, A-1040 Wien, Favoritenstraße 38/18/1 Adalbert Krims, Univ. Prof. Dr. Walter (Öffnungszeiten: Dienstag 14.00-18.00) Sauer, Abg. z. Ltg. Godwin Schuster, Dr. Tel. 01/505 44 84 Gabriele Slezak. Fax 01/505 44 84-7 URL: http://www.sadocc.at das quartalsweise erscheinende Magazin INDABA monatliche Veranstaltungen „Forum Südliches Afrika“ Stadtspaziergänge „Afrikanisches Wien“ Projekt Schwimmunterricht in KwaZulu/Natal Interessierte Einzelpersonen und Institutionen können SADOCC durch ihren Beitritt als unterstützende Mitglieder fördern. In der Mitgliedsgebühr von jährlich EUR 22,– (für Institutionen EUR 40,–) sind sämtliche Aussendungen und Einladungen enthalten. Das Abonnement von INDABA kostet EUR 13,–. Elfriede Pekny-Gesellschaft derung von Abo- oder Mitgliedsbeitrags-Einzahlungen auf unser Die Elfriede Pekny-Gesellschaeichft zu (benanntr För nach der Konto bei der BA-CA, BLZ 12000, Konto 610 512 006; n African Studies in Österr etärin) ist Spenden erbeten auf Konto: Postsparkasse, BLZ 60000, Souther - Kto-Nr. -

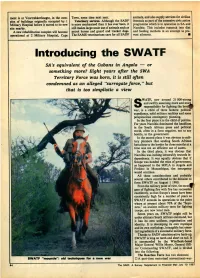

Introducing the SWATF

ment is at Voortrekkerhoogte, in the com Town, some time next year. animals, and also supply services for civilian plex of buildings originally occupied by 1 Veterinary services. Although the SADF livestock as part of the extensive civic action Military Hospital before it moved to its new is more mechanised than it has ever been, it programme which is in operation in SA and site nearby. still makes large-scale use of animals such as Namibia. This includes research into diet A new rehabilitation complex will become patrol horses and guard and tracker dogs. and feeding methods in an attempt to pre operational at 2 Military Hospital, Cape The SAMS veterinarians care for all SADF vent ailments. ■ Introducing the SWATF SA’s equivalent of the Cubans in Angola — or something more? Eight years after the SWA Territory Force was born, it is still often condemned as an alleged "surrogate force," but that is too simplistic a view WATF, now around 21 000-strong and swiftly assuming more and more S responsibility for fighting the bord(^ war, is a child of three fathers: political expediency, solid military realities and some perspicacious contingency planning. In the first place it is the child of politics. For years Namibia dominated the headlines in the South African press and political world, often in a form negative, not to say hostile, to the government. In the second place it was obvious to mili tary planners that sending South African battalions to the border for three months at a time was not an efficient use of assets. -

A Study Into the Meanings of Sports As a Medium of HIV Awareness in a South African Township

Active HIV Awareness A study into the meanings of sports as a medium of HIV awareness in a South African township Utrecht University Utrecht School of Governance Organization, Culture & Management Author: Maikel Waardenburg Utrecht, February 2006 Active HIV Awareness A study into the meanings of sports as a medium of HIV awareness in a South African township Utrecht University Utrecht School of Governance Organization, Culture & Management Supervisor: drs. Marinette Oomen Author: Maikel Waardenburg Himalaya 164 3524 XJ Utrecht, the Netherlands [email protected] Student number: 0144274 Utrecht, February 2006 The picture on the cover of this document is property of Martijn Bergmans Extensive paper written for the final year of the study ‘Public Administration & Organizational Science’ at Utrecht University Active HIV Awareness Contents Summary iv List of Tables and Figures vi List of Abbreviations vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Research Design 3 1.1 Central Research Question 3 1.2 Research Paradigm 4 1.3 Research Object 5 1.4 Research Methods 5 1.4.1 Observations 5 1.4.2 Interviews 6 1.4.3 Participation 7 1.5 Public and Scientific Relevance 8 Chapter 2 The Big Picture 10 2.1 Early South Africa 10 2.2 Political Struggle in South Africa 11 2.3 Present-day South Africa 13 2.3.1 Present-day Government & Politics 14 2.3.2 Economy of South Africa 16 2.3.3 Socio-cultural features of South Africa 17 2.4 The HIV/AIDS Pandemic in South Africa 17 2.4.1 HIV Determinants in South Africa 19 2.4.2 Government’s Response -

New Contracts

Third Issue 2015 New Contracts Milestone to Boost Denel’s Agreement with UN, Armoured a Huge Benefit for Vehicle Business Mechem’s Business Dubai Airshow an Opportunity Denel Support for Denel to Market its Enables Rapid Aerospace Capabilities Growth of Enterprise DENEL GROUP VALUES PERFORMANCE WE EMBRACE OPERATIONAL EXCELLENCE. INTEGRITY WE ARE HONEST, TRUTHFUL AND ETHICAL. INNOVATION WE CREATE SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT SOLUTIONS. CARING WE CARE FOR OUR PEOPLE, CUSTOMERS, COMMUNITIES, NATIONS AND THE ENVIRONMENT. ACCOUNTABILITY WE TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ALL OUR ACTIONS. Contents Issue highlights 2 Editor-in-Chief 3 Year-end Message from the Acting Group CEO 3 A Dozen Achievements – Top 12 Highlights of 2015 4 Accolades Keep Rolling in for Denel 4 Strong Support for Denel Demonstrated in Parliament 4 Young Engineers Conquer the Systems at Annual Challenge 05 5 New Contracts to Boost Denel’s Armoured Vehicle Business 6 Dubai Airshow an Opportunity to Market our Aerospace Capabilities 7 Strong Support for Growth of Ekurhuleni Aerotropolis in Gauteng 8 Iconic Denel Products Offer Backdrop for Paintball Warriors 9 Denel Support Enables Rapid Growth for Thuthuka 10 Denel Participates at SA Innovation Summit 09 10 Clever Robot Detects Landmines to Save Lives 11 Denel Products on Show in London 12 Milestone Agreement with UN Benefits Mechem Business 13 Training Links with Cameroon Grow Stronger 14 Empowering a Girl Child to Fly High 14 DTA Opens Doors to Training Opportunities 15 Denel Vehicle Systems Inspires Youthful Audience 12 15 High praise for Mechem team in Mogadishu 16 Preserving Denel’s Living Heritage 18 Celebrating Pioneering Women in Words and Pictures 20 Out and About in Society 16 Editor’s Note We would like to hear from you! Denel Insights has been created as an external communication platform to keep you – our stakeholders – informed about the projects and developments within our Group. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I Would

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to record and extend my indebtedness, sincerest gratitude and thanks to the following people: * Mr G J Bradshaw and Ms A Nel Weldrick for their professional assistance, guidance and patience throughout the course of this study. * My colleagues, Ms M M Khumalo, Mr I M Biyela and Mr L P Mafokoane for their guidance and inspiration which made the completion of this study possible. " Dr A A M Rossouw for the advice he provided during our lengthy interview and to Ms L Snodgrass, the Conflict Management Programme Co-ordinator. " Mrs Sue Jefferys (UPE) for typing and editing this work. " Unibank, Edu-Loan (C J de Swardt) and Vodakom for their financial assistance throughout this work. " My friends and neighbours who were always available when I needed them, and who assisted me through some very frustrating times. " And last and by no means least my wife, Nelisiwe and my three children, Mpendulo, Gabisile and Ntuthuko for their unconditional love, support and encouragement throughout the course of this study. Even though they were not practically involved in what I was doing, their support was always strong and motivating. DEDICATION To my late father, Enock Vumbu and my brother Gcina Esau. We Must always look to the future. Tomorrow is the time that gives a man or a country just one more chance. Tomorrow is the most important think in life. It comes into us very clean (Author unknow) ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF ABBREVIATIONS/ ACRONYMS USED ANC = African National Congress AZAPO = Azanian African Peoples -

Wrecking Ball

WRECKING BALL Why Permanent Technological Unemployment, a Predictable Pandemic and Other Wicked Problems Will End South Africa’s Experiment in Inclusive Democracy by Stu Woolman TERMS of USE This electronic version of the book is available exclusively on the NISC website for free download to use in research or private study. It may not be re-posted on book or other digital repositories that allow systematic sharing or download. For any commercial or other uses please contact the publishers, NISC (Pty) Ltd. Print copies of this book as well as e-Book versions available for online ordering from the African Books Collective and Amazon.com. © NISC (Pty) Ltd WRECKING BALL Why permanent technological unemployment, a predictable pandemic and other wicked problems will end South Africa’s experiment in inclusive democracy Wrecking Ball explores, in an unprecedented manner, a decalogue of wicked problems that confronts humanity: Nuclear proliferation, climate change, pandemics, permanent technological unemployment, Orwellian public and private surveillance, social media that distorts reality, cyberwarfare, the fragmentation of democracies, the inability of nations to cabin private power, the failure of multinational institutions to promote collaboration and the deepening of autocratic rule in countries that have never known anything but extractive institutions. Collectively, or even severally, these wicked problems constitute crises that could end civilisation. Does this list frighten you, or do you blithely assume that tomorrow will be just like yesterday? Wrecking Ball shows that without an inclusive system of global governance, the collective action required to solve those wicked problems falls beyond the remit of the world’s 20 inclusive democracies, 50 flawed democracies and 130 extractive, elitist autocracies. -

Jamie Stern-Weiner Tis Ebook Edition Published by Verso 2019

anti-semitism and the labour party Anti-Semitism and the Labour Party Edited by Jamie Stern-Weiner Tis ebook edition published by Verso 2019 All rights reserved Te moral rights of the authors have been asserted Verso UK: 6 Meard St, London, W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay St, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Lef Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78960-671-3 ‘Corbyn Under Fire’ and ‘Te Never Ending Story’, © Daniel Finn 2018, frst appeared in Jacobin. ‘Jeremy Corbyn is an Anti-Racist, Not an Anti-Semite’ © Jospehn Finlay, 2019, frst appeared in Times of Israel. 'Smoke Without Fire: Te Myth of the 'Labour Antisemitism Crisis’ © Jamie Stern-Weiner and Alan Maddison, 2019. ‘Te Chimera of British Anti-Semitism (and How Not to Fight It if it Were Real)’, frst appeared on Verso Blog © Norman Finkelstein, 2019; ’60 Times Jeremy Corbyn Stood with Jewish People’ © @ToryFibs; ‘Briefng for Canvassers: Challenging false allegations of antisemitism’ and ‘Te Riverside Scandal’ with permission from Jewish Voice for Labour; ‘A Disinformation Campaign’ © Media Reform Coalition, 2019; ‘Te Fake News Nazi: Corbyn, Williamson and the Anti-Semitism Scandal’ from Medians © David Edwards, 2019; ‘Is the Guardian Institutionally Antisemitic?’ and ‘Labour Party Conference or Nuremberg Rally? Assessing the Evidence’ from author’s blog, © Jamie Stern-Weiner 2019; ‘Hue and Cry over the UCU’ © Richard Kuper 2019; with permission of OpenDemocracy; ‘Why the Labour Party Should Not Adopt the IHRA Defnition or Any Other Defnition of Antisemitism’ from author’s -

Metalworking News May 2016 PDF.Pdf

METALWORKING NEWS 2 Editor’s Comment 4 Viewpoint 6 Industry News The first double-sided, multi-edge milling concept; SA arms and weapons legislation; Boeing, Paramount Group; First train expected; Pressure Die Castings wins contracts; Industry 4.0; Toyota SA; Engineering Community Conference 2016; Emergency steel tariffs; Volkswagen; Denel-Gupta deal; New auto plants; Mitsubishi Electric; World Power Products; APDP incentive; Ford; Aluminium hub; Tysica; Alstom; Aluminium value chain; WD Hearn 42 Shopfront Focus Moulding a niche; Resolution Circle; Moving into fabricating 62 Better Production IT and OT converging in the Factory of the Future 66 International News Hexagon; Conzzeta; Okuma; Robotics market; Global machine tool; MBK Partners; Schuler; Prima Power; Selective laser melting technique; AM will not threaten metalworking; “Bible of the Metalworking Industries”; Radan; Unmanned war vehicle system; 3D printing; Engel; Alcoa 84 Product Review PolyWorks® 2016; Victor CNC; Yaskawa; Haas; Hypertherm; Holemaking & drilling options; BLM Lasertube LT8; Iscar; You Ji YV-600E2T; Tongtai; FixtureBuilder 3D-modelling software; Alpha Laser; Studer; Hurco; HyperWorks 14.0; solidThinking Inspire 2016; Nikon; Mastercam X9; Tungaloy’s DoForce-Tri; Trumpf METALWORKING NEWS V 15. 2 May 2016 1 EDITOR’S COMMENT Look after our skills and resources or a long time the mining industry was the Volume 15 Number 2 well-being of our economy. It is an industry May 2016 that affects all of us and has a long F Editor historical background. Its real beginning dates back to the 19th century, when the diamond and Bruce Crawford gold rushes started. While the history of gold Online Editor mining is often presumed to postdate that of Damon Crawford diamonds, the precious metal was, in fact, discovered, and the first mine established, at Editorial Board roughly the same time as the diamond rush, Professor Dimitri Dimitrov, they say.