Wrecking Ball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Restoration of Tulbagh As Cultural Signifier

BETWEEN MEMORY AND HISTORY: THE RESTORATION OF TULBAGH AS CULTURAL SIGNIFIER Town Cape of A 60-creditUniversity dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in the Conservation of the Built Environment. Jayson Augustyn-Clark (CLRJAS001) University of Cape Town / June 2017 Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment: School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ‘A measure of civilization’ Let us always remember that our historical buildings are not only big tourist attractions… more than just tradition…these buildings are a visible, tangible history. These buildings are an important indication of our level of civilisation and a convincing proof for a judgmental critical world - that for more than 300 years a structured and proper Western civilisation has flourished and exist here at the southern point of Africa. The visible tracks of our cultural heritage are our historic buildings…they are undoubtedly the deeds to the land we love and which God in his mercy gave to us. 1 2 Fig.1. Front cover – The reconstructed splendour of Church Street boasts seven gabled houses in a row along its western side. The author’s house (House 24, Tulbagh Country Guest House) is behind the tree (photo by Norman Collins). -

Which Is the Largest Manufacturer of Defence Equipment in South Africa and Operates in the Military Aerospace and Landward Defence Environment

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY DENEL Denel is a state-owned company (SOC), which is the largest manufacturer of defence equipment in South Africa and operates in the military aerospace and landward defence environment. Denel is an important defence contractor in the domestic market and a key supplier to the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) both as original equipment manufacturer (OEM) and for the overhaul, maintenance, repair, refurbishment and upgrade of equipment in the SANDF’s arsenal. Denel reports to the Minister of Public Enterprises who appoints an independent board of directors to oversee an executive management team, managing the day-to-day operations. The executive management team also manages several business divisions and associated companies, including Denel Aeronautics, Denel Maritime, Pretoria Metal Pressings, Denel Dynamics, Denel Land Systems, Denel Vehicle Systems (Pty) Ltd and Denel Aerostructures SOC Ltd. With the release of the #Guptaleaks in May 2017, the actions and good governance of the board of directors were brought into question, not only because of the Denel-Asia deal, but also because of the relationships between key decision makers and the Gupta family. OUTA explores the capturing of Denel in this submission and provides supporting evidence. Before July 2015, Denel was led by a board of directors chaired by Riaz Saloojee. This board’s direction resulted in a series of profitable years as set out in the second issue of a 2015 Denel- issued communique. Denel had good prospects for its future and an order book of more than R35 billion and the group CFO Fikile Mhlonto was nominated as Public CFO of the year. -

Declaration of Union Buildings, Portion of Farm

STAATSKOERANT, 2 DESEMBER 2013 No. 37101 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF ARTS AND CULTURE No. 931 2 December 2013 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE NOTICE FOR THE DECLARATION OF Union Buildings (Portions of the farm Elandspoort 357-JR), City of Tshwane, Gauteng; 120 Plein Street, Cape Town (Located on Erf 3742, 3745 - 3746 and 9240, Cape Town) and Tuynhuys (Located on Ed 95165, Cape Town), Parliamentary Precinct, Cape Town, Western Cape By virtue of the powers vested in the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) in terms of Section 27 (5) of the National heritage Resources Act No. 25 of 1999, SAHRA hereby declares the Union Buildings, Portions of the farm Elandspoort 357-JR, City of Tshwane, Gauteng; 120 Hein Street, Cape Town (Located on Erf 3742, 3745 - 3746 and 9240, Cape Town) and Tuynhuys (Located on Erf 95165), Parliamentary Precinct, as National Heritage Sites. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE The Union Buildings Complex The Union Buildings complex is a unique and exceptional example of the interface between architecture and landscaping, but more importantly, it is a symbol of South Africa with notable political significance, both historically and in contemporary terms. While the City of Tshwane has developed around it, the Union Buildings, regarded as one of the stateliest buildings in the country, has remained a symbol of the Presidency and the seat of power of the Republic of South Africa. 120 Plein Street Bordering Stalplein is the 18 -floor office complex known as 120 Plein Street. The official opening of the building took place on 11 February 1972.It was built to accommodate Ministers, Deputy Ministers, Heads and officials of state departments during parliamentary sessions. -

Overcoming the Legacy of Exclusion in South Africa

Republic of South Africa Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized An Incomplete Transition: Overcoming the Legacy of Exclusion in South Africa Public Disclosure Authorized Background note Corporate Governance in South African State-Owned Enterprises Sunita Kikeri Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Corporate Governance in South African State-Owned Enterprises Sunita Kikeri1 Introduction State-owned enterprises (SOEs) play an important role in the South African economy. Since 1994 SOEs have been a significant vehicle for achieving economic growth and poverty reduction. They are especially important vehicles for addressing market failure and for delivering key infrastructure services such as energy, transport, and water that allow the economy to grow while ensuring equity through access and quality of social services to all citizens. Strengthening their role and performance is a key component of the Developmental State agenda. This agenda addresses the key challenges facing South Africa: high poverty and unemployment levels; skewed distribution and maintenance of infrastructure; unequal distribution of land and capital; and growing disparities between the rich and poor. The Government’s New Growth Path (NGP), which sets a target of creating five million additional jobs by 2020, specifically calls on SOEs to play a key developmental role. Other policies such as the National Development Plan (NDP), the Medium-Term Strategic Framework (MTSF), and the Industrial Policy Action Plan also highlight the role of SOEs as major contributors to infrastructure development and to economic restructuring, while the Nine-Point Plan, which outlines Government priorities, includes addressing the electricity challenge and supporting reforms in SOEs. Through these initiatives, the Government’s goal is to ensure that SOEs deliver on broader developmental goals and that they support the transformation and competitiveness of the economy. -

Denel Annual Report 2004

Denel Annual Report 2004 Denel www.denel.co.zawww.denel.co.za Global suppliers of world-class products Annual Report 2004 CONTENTS Business philosophy 1 Commercial and IT Business 28 Consolidated statements of changes in equity 60 Our business 2 Strategic relationships 32 Consolidated cash flow statements 61 Financial highlights 3 Corporate governance 33 Notes to the cash flow statements 62 Chairman’s statement 4 Safety, health and environment 42 Board of Directors 8 Ten-year review 44 Notes to the annual financial statements 63 Chief Executive Officer’s message 10 Value added statement 46 Subsidiaries and Operational review 14 Report of the independent auditors 47 associated companies 96 Executive committee 18 Directors’ report 48 Report of the independent auditors Aerospace 20 Consolidated balance sheets 58 (on PFMA) 98 Land systems 24 Consolidated income statements 59 Contact details 100 GRAPHICOR 30858 Business philosophy DENEL ANNUAL REPORT 2004 1 OUR PURPOSE To be the leading South African defence company, supplying systems, products and services in selected niche areas to the domestic security services and to customers in global markets. To be a prime contractor and systems integrator in selected areas. To be a guardian of strategic technologies in our sector and a catalyst in South Africa for the development of future technologies. To grow and operate profitably to provide jobs, to develop our people, and to provide training for others where we have the capacity. OUR VALUES SHARED VALUES Customer focus Innovation Initiative Integrity TEAM VALUES Denel is a market and people driven company. Employees/colleagues at all levels working together as a team are the key to Denel’s success. -

How Cape Town Averted ‘Day Zero,’ 2017 – 2018

KEEPING THE TAPS RUNNING: HOW CAPE TOWN AVERTED ‘DAY ZERO,’ 2017 – 2018 SYNOPSIS In 2017, Cape Town, South Africa, was on a countdown to disaster. An unprecedented and wholly unforeseen third consecutive year of drought threatened to cut off water to the city’s four million citizens. Faced with the prospect of running dangerously low on potable water, local officials raced against time to avert “Day Zero”—the date on which they would have to shut off drinking water to most businesses and homes in the city. Cape Town’s government responded effectively to the fast-worsening and potentially cataclysmic situation. Key to the effort was a broad, multipronged information campaign that overcame skepticism and enlisted the support of a socially and economically diverse citizenry as well as private companies. Combined with other measures such as improving data management and upgrading technology, the strategy averted disaster. By the time the drought eased in 2018, Capetonians had cut their water usage by nearly 60% from 2015 levels. With each resident using little more than 50 liters per day, Cape Town achieved one of the lowest per capita water consumption rates of any major city in the world. The success set a benchmark for cities around the world that confront the uncertainties of a shifting global climate. Leon Schreiber drafted this case study based on interviews conducted in Cape Town, South Africa, in November 2018. Case published February 2019. INTRODUCTION In the waning days of 2017, temperatures municipal drinking water each resident could use rose as summer returned to Cape Town, South at home without incurring steep surcharges. -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

A Foreign Policy Handbook

A FOREIGN POLICY HANDBOOK An Overview of South African Foreign Policy in Context FOr PArliAment 2014 B d e l t r te o r W Af er rica • Bett A FOREIGN POLICY HANDBOOK An Overview of South Africa’s Foreign Policy in Context FOr PArliAment 2014 Acknowledgments the institute for Global Dialogue associated with Unisa would like to acknowledge the Friedrich-ebert-Stiftung (FeS) for their support for the institute’s parliamentary diplomacy research. Appreciation is also expressed to ms lineo mosala, Content Adviser for the Portfolio Committee on international relations and Cooperation, for her assistance and guidance in making this document possible. Project team Dr Siphamandla Zondi (iGD) Dr lesley masters (iGD) mr Wayne Jumat (iGD) ms romi reinecke (FeS) mr robert Boldt (FeS) layout Clara mupopiwa iSBn 978-0-620-62445-9 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SOUTH 3. AN OVERVIEW OF 05 - 06 AFRICA’S SOUTH AFRICA’S FOREIGN FOREIGN Policy Policy 1994-2014 07 - 12 13 -21 4. SOUTH 5. DEVelopMents 6. Concepts AFRICA’S FOREIGN IN diploMacy 33 - 37 Policy AND its 27 - 32 Stakeholders 22 - 26 7. SOUTH AFRICA, 8. ACRONYMS AND 9. Contact International ABBREViations Details for Organisations 48 SELECTED AND DepartMents PLUrilateralisM 49 - 56 38 - 46 10. List OF KEY 11. ABOUT RESOURCES THE IGD 55 - 56 57 - 59 1 INTRODUCTION An Overview of South African Foreign Policy 1994-2014 he Parliament of South Africa has a proud tradition of engagement in South Africa’s foreign policy. The Portfolio Committee on International Relations and Cooperation (the Committee) Thas been engaged in debate on numerous issues, from human rights to economic diplomacy, in shaping South Africa’s approach towards international relations. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Written Statement of Mxolisi Mgojo, the Chief Executive Officer Of

1 PUBLIC ENTERPRISES PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO ESKOM, TRANSNET AND DENEL WRITTEN STATEMENT OF MXOLISI MGOJO, THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER OF EXXARO RESOURCES LIMITED INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 COST-PLUS MINES VERSUS COMMERCIAL MINES .......................................... 5 THE SO-CALLED “PRE-PAYMENT” FOR COAL ................................................. 9 PREJUDICE TO EXXARO’S COST-PLUS MINES AND MAFUBE ..................... 11 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 11 Arnot mine ............................................................................................................. 12 Eskom’s failure to fund land acquisition ................................................................. 12 Non-funding of operational capital at Arnot ............................................................ 14 The termination of Arnot’s CSA .............................................................................. 15 Conclusion of the Arnot matters ............................................................................. 19 Mafube mine.......................................................................................................... 19 Matla mine ............................................................................................................. 21 Non-funding of capital of R1.8 billion for mine 1 ................................................... -

New Contracts

Third Issue 2015 New Contracts Milestone to Boost Denel’s Agreement with UN, Armoured a Huge Benefit for Vehicle Business Mechem’s Business Dubai Airshow an Opportunity Denel Support for Denel to Market its Enables Rapid Aerospace Capabilities Growth of Enterprise DENEL GROUP VALUES PERFORMANCE WE EMBRACE OPERATIONAL EXCELLENCE. INTEGRITY WE ARE HONEST, TRUTHFUL AND ETHICAL. INNOVATION WE CREATE SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT SOLUTIONS. CARING WE CARE FOR OUR PEOPLE, CUSTOMERS, COMMUNITIES, NATIONS AND THE ENVIRONMENT. ACCOUNTABILITY WE TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ALL OUR ACTIONS. Contents Issue highlights 2 Editor-in-Chief 3 Year-end Message from the Acting Group CEO 3 A Dozen Achievements – Top 12 Highlights of 2015 4 Accolades Keep Rolling in for Denel 4 Strong Support for Denel Demonstrated in Parliament 4 Young Engineers Conquer the Systems at Annual Challenge 05 5 New Contracts to Boost Denel’s Armoured Vehicle Business 6 Dubai Airshow an Opportunity to Market our Aerospace Capabilities 7 Strong Support for Growth of Ekurhuleni Aerotropolis in Gauteng 8 Iconic Denel Products Offer Backdrop for Paintball Warriors 9 Denel Support Enables Rapid Growth for Thuthuka 10 Denel Participates at SA Innovation Summit 09 10 Clever Robot Detects Landmines to Save Lives 11 Denel Products on Show in London 12 Milestone Agreement with UN Benefits Mechem Business 13 Training Links with Cameroon Grow Stronger 14 Empowering a Girl Child to Fly High 14 DTA Opens Doors to Training Opportunities 15 Denel Vehicle Systems Inspires Youthful Audience 12 15 High praise for Mechem team in Mogadishu 16 Preserving Denel’s Living Heritage 18 Celebrating Pioneering Women in Words and Pictures 20 Out and About in Society 16 Editor’s Note We would like to hear from you! Denel Insights has been created as an external communication platform to keep you – our stakeholders – informed about the projects and developments within our Group. -

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

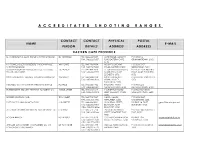

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714