Overcoming the Legacy of Exclusion in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydrocarbon Exploration Activities in South Africa

Hydrocarbon Exploration Activities in South Africa Anthea Davids [email protected] AAPG APRIL 2014 Petroleum Agency SA - oil and gas exploration and production regulator 1. Update on latest exploration activity 2. Some highlights and important upcoming events 3. Comments on shale gas Exploration map 3 years ago Exploration map 1 year ago Exploration map at APPEX 2014 Exploration map at AAPG ICE 2014 Offshore exploration SunguSungu 7 Production Rights 12 Exploration Rights 16 Technical Cooperation Permits Cairn India (60%) PetroSA (40%) West Coast Sungu Sungu Sunbird (76%) Anadarko (65%) PetroSA (24%) PetroSA (35%) Thombo (75%) Shallow-water Afren (25%) • Cairn India, PetroSA, Thombo, Afren, Sasol PetroSA (50%) • Sunbird - Production Shell International Sasol (50%) right around Ibhubesi Mid-Basin – BHP Billiton (90%) • Sungu Sungu Global (10%) Deep water – • Shell • BHP Billiton • OK Energy Southern basin • Anadarko and PetroSA • Silwerwave Energy PetroSA (20%) • New Age Anadarko (80%) • Rhino Oil • Imaforce Silver Wave Energy Greater Outeniqia Basin - comprising the Bredasdorp, Pletmos, Gamtoos, Algoa and Southern Outeniqua sub-basins South Coast PetroSA, ExonMobil with Impact, Bayfield, NewAge and Rift Petroleum in shallower waters. Total, CNR and Silverwave in deep water Bayfield PetroSA Energy New Age(50%) Rift(50%0 Total CNR (50%) Impact Africa Total (50%) South Coast Partnership Opportunities ExxonMobil (75%) East Impact Africa (25%) Coast Silver Wave Sasol ExxonMobil (75%) ExxonMobil Impact Africa (25%) Rights and major -

Sidssa Sustainable Infrastructure Development Symposium South Africa

SIDSSA SUSTAINABLE INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT SYMPOSIUM SOUTH AFRICA 23 JUNE 2020 levels for 2020. If, on the other hand, infections rebound and a second round of lockdowns is “We are institutionalising the required in major economies, it is predicted that the global economy could shrink by almost 8 percent SIDS methodology as a new way in 2020 and grow at only around 1 percent in 2021. of packaging and preparing This crisis provides an opportunity for the Government to seriously consider key reforms necessary to revive and transform the economy to support inclusive. projects for funding.” It is evident that unlocking the potential of South Africa’s economy requires a range of reforms electricity and municipal services. This enables agriculture due to its employment creation capacity, in areas including infrastructure sector market, more efficient supply chains, increases productivity and the upstream agro-processing opportunities it regulation and operation of SOEs, and the investment and drives sustainable economic growth and a fast offers which leads to revitalization of rural economies. climate for private enterprises. The pandemic pace of job creation. Government must invest in Integrated human settlements is another area of made the need for these changes indisputable. infrastructure to enable businesses to accelerate focus in the SIDS process. Our promise of providing employment and grow the economy, which will also decent housing to low-income communities is not The Minister of Finance has put forward a package of allow government finances to stabilize and recover. totally fulfilled. We are fashioning innovative building reforms to address macroeconomic imbalances and However, infrastructure investment must present technologies, and financing instruments to allow the boost long-run growth as the crisis eases. -

Denel Annual Report 2004

Denel Annual Report 2004 Denel www.denel.co.zawww.denel.co.za Global suppliers of world-class products Annual Report 2004 CONTENTS Business philosophy 1 Commercial and IT Business 28 Consolidated statements of changes in equity 60 Our business 2 Strategic relationships 32 Consolidated cash flow statements 61 Financial highlights 3 Corporate governance 33 Notes to the cash flow statements 62 Chairman’s statement 4 Safety, health and environment 42 Board of Directors 8 Ten-year review 44 Notes to the annual financial statements 63 Chief Executive Officer’s message 10 Value added statement 46 Subsidiaries and Operational review 14 Report of the independent auditors 47 associated companies 96 Executive committee 18 Directors’ report 48 Report of the independent auditors Aerospace 20 Consolidated balance sheets 58 (on PFMA) 98 Land systems 24 Consolidated income statements 59 Contact details 100 GRAPHICOR 30858 Business philosophy DENEL ANNUAL REPORT 2004 1 OUR PURPOSE To be the leading South African defence company, supplying systems, products and services in selected niche areas to the domestic security services and to customers in global markets. To be a prime contractor and systems integrator in selected areas. To be a guardian of strategic technologies in our sector and a catalyst in South Africa for the development of future technologies. To grow and operate profitably to provide jobs, to develop our people, and to provide training for others where we have the capacity. OUR VALUES SHARED VALUES Customer focus Innovation Initiative Integrity TEAM VALUES Denel is a market and people driven company. Employees/colleagues at all levels working together as a team are the key to Denel’s success. -

Igas (Pipe- Petrosa, Sasol Igas (Pipelines Packing) and LNG Gas) Nuclear Nuclear Regulator Eskom, NECSA

PCE & DOE DIALOGUE CEF GROUP PRESENTATION 9 JUNE 2015 Objectives . Give a holistic overview of CEF Group of Companies in delivering on the national security of energy supply and share often forgotten historical achievements made by CEF. Provide an overarching overview of Energy Options for context and background to fully appreciate the role of CEF and its importance from a national economic perspective and the role played by each entity. Address key CEF Group sustainability strategic challenges and in particular at PetroSA and what the joint efforts of the CEF & PetroSA Boards is trying to achieve in turning around the fortunes of PetroSA in a holistic manner with key timelines and objectives. Overview of the Group strategic objectives for delivering on the CEF Mandate and approach through Vision 2025 to drive Group sustainability in line with the “Redefined Role of CEF”. in support of the DoE, MTSF and SONA (June 2014). The team will dwell on the CEF Road Map. Way forward and the collective support and alignment required from all stakeholders in finding long term solutions for various solutions. Page . 2 Agenda 1 Overview of Energy Options for Economic Transformation & Sustainability 2 Overview of the CEF Mandate, Legislation and Historical Context 3 How the CEF Group is Geared to deliver on Security of Supply 4 Foundations for Group Sustainability 5 Focus on PetroSA Sustainability 6 Group Strategic Objectives 7 Summary of Group Initiatives 8 Policy Gaps 9 Support required from PCE & Way Forward Page . 3 Overview of Energy Options for -

Overview of the Liquid Fuels Sector in South Africa

DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY PRESENTATION TO THE IEP STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION NELSPRUIT 19 NOVEMBER 2013 PRESENTED BY: MJ MACHETE OVERVIEW OF THE LIQUID FUELS SECTOR IN SOUTH AFRICA BY MOHUDI MACHETE Historical Excursion On The Liquid Fuels Sector • Liquid Fuels sector is more than 100 years in SA • Almost all petroleum products sold in South Africa were imported as refined product by the respective wholesale companies who distributed this to their branded retailers and various commercial customers. • In the first half of the 1950s, the government-initiated project to produce oil from South Africa’s abundant low- grade coal reserves, which saw the formation of the South African Coal, Oil and Gas Corporation Limited, later called Sasol Limited • In 1955 the first oil-from-coal-synthetic fuel plant – Sasol One – was constructed Historical Excursion On The Liquid Fuels Sector • Period of the Sasol Supply Agreements (SSA) or the Main Supply Agreement (MSA) between Sasol and the major distributors. • The international oil crisis of 1973 accelerated government’s plans to expand the capacity of Sasol’s oil-from-coal facilities • The UN’s imposition in 1977 of a mandatory crude oil embargo underlined these concerns, as did the Iranian revolution of 1979. • Sasol Two and Sasol Three were commissioned at Secunda, also in the inland region, in 1980 and 1982 respectively. Historical Excursion On The Liquid Fuels Sector • In 1987 when natural gas condensate was discovered off shore, the Government built a gas-to-liquids plant Mossel Bay (now owned and operated by PetroSA). • The Mossgas plant commenced production in late 1992. • Government, in addition to its direct intervention through Sasol to secure indigenous sources of petroleum product, also encouraged private sector initiatives aimed at addressing these concerns. -

Petrosa Template

Gas to Liquid Technologies March 2012 Gareth Shaw The Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (Soc) Ltd Reg. No. 1970/008130/07 The Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (Pty) Ltd Reg. No. 1970/008130/07 Objectives What role should GTL technology play in future energy supply in South Africa? • List of GTL technologies to be considered • Major characteristics: • Costs • Emissions • Jobs • Water use The Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd Reg. No. 1970/008130/07 2 GTL role in future supply The Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd Reg. No. 1970/008130/07 3 Regional energy resource mix • East coast and West coast gas • Shale gas (not shown below) Current Operations The Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd Reg. No. 1970/008130/07 Source: DOE, RSA 1 4 Demand for liquid fuels The Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd Reg. No. 1970/008130/07 Source: PFC Energy 2 5 Gas reserves required to meet future growth GTL technology is now designed to make diesel In 2025 3.3 Tcf of gas will be required to meet 50 000 b/d diesel demand growth. In 2030 a further 4.6 Tcf of gas will be required to meet the 70 000 b/d diesel demand growth. The Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd Reg. No. 1970/008130/07 Source: PFC Energy 2 6 GTL growing internationally Qatar Nigeria Malaysia Qatar Sasolburg Mossel Bay The Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd Reg. -

Written Statement of Mxolisi Mgojo, the Chief Executive Officer Of

1 PUBLIC ENTERPRISES PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO ESKOM, TRANSNET AND DENEL WRITTEN STATEMENT OF MXOLISI MGOJO, THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER OF EXXARO RESOURCES LIMITED INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 COST-PLUS MINES VERSUS COMMERCIAL MINES .......................................... 5 THE SO-CALLED “PRE-PAYMENT” FOR COAL ................................................. 9 PREJUDICE TO EXXARO’S COST-PLUS MINES AND MAFUBE ..................... 11 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 11 Arnot mine ............................................................................................................. 12 Eskom’s failure to fund land acquisition ................................................................. 12 Non-funding of operational capital at Arnot ............................................................ 14 The termination of Arnot’s CSA .............................................................................. 15 Conclusion of the Arnot matters ............................................................................. 19 Mafube mine.......................................................................................................... 19 Matla mine ............................................................................................................. 21 Non-funding of capital of R1.8 billion for mine 1 ................................................... -

New Contracts

Third Issue 2015 New Contracts Milestone to Boost Denel’s Agreement with UN, Armoured a Huge Benefit for Vehicle Business Mechem’s Business Dubai Airshow an Opportunity Denel Support for Denel to Market its Enables Rapid Aerospace Capabilities Growth of Enterprise DENEL GROUP VALUES PERFORMANCE WE EMBRACE OPERATIONAL EXCELLENCE. INTEGRITY WE ARE HONEST, TRUTHFUL AND ETHICAL. INNOVATION WE CREATE SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT SOLUTIONS. CARING WE CARE FOR OUR PEOPLE, CUSTOMERS, COMMUNITIES, NATIONS AND THE ENVIRONMENT. ACCOUNTABILITY WE TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ALL OUR ACTIONS. Contents Issue highlights 2 Editor-in-Chief 3 Year-end Message from the Acting Group CEO 3 A Dozen Achievements – Top 12 Highlights of 2015 4 Accolades Keep Rolling in for Denel 4 Strong Support for Denel Demonstrated in Parliament 4 Young Engineers Conquer the Systems at Annual Challenge 05 5 New Contracts to Boost Denel’s Armoured Vehicle Business 6 Dubai Airshow an Opportunity to Market our Aerospace Capabilities 7 Strong Support for Growth of Ekurhuleni Aerotropolis in Gauteng 8 Iconic Denel Products Offer Backdrop for Paintball Warriors 9 Denel Support Enables Rapid Growth for Thuthuka 10 Denel Participates at SA Innovation Summit 09 10 Clever Robot Detects Landmines to Save Lives 11 Denel Products on Show in London 12 Milestone Agreement with UN Benefits Mechem Business 13 Training Links with Cameroon Grow Stronger 14 Empowering a Girl Child to Fly High 14 DTA Opens Doors to Training Opportunities 15 Denel Vehicle Systems Inspires Youthful Audience 12 15 High praise for Mechem team in Mogadishu 16 Preserving Denel’s Living Heritage 18 Celebrating Pioneering Women in Words and Pictures 20 Out and About in Society 16 Editor’s Note We would like to hear from you! Denel Insights has been created as an external communication platform to keep you – our stakeholders – informed about the projects and developments within our Group. -

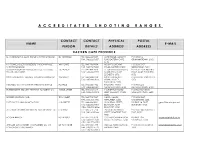

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

SCAM to SUPPLIERS and SERVICE PROVIDERS of Petrosa

WARNING SCAM TO SUPPLIERS AND SERVICE PROVIDERS of PetroSA The PetroSA Group Supply Chain Department, wishes to alert suppliers about individuals who defraud unsuspecting businesses, disguising as PetroSA Group Supply Chain (GSC) Representatives. The scam involves fraudsters using the PetroSA letterhead to send out fake requests to supply equipment and goods. Although the contact person’s name on the letter may be that of an existing PetroSA employee, the contact details (email and telephone) are not the same as that of PetroSA’s Group Supply Chain Department. PetroSA utilises an internet based eprocurement system to source goods and services. Open and closed tenders are normally available to suppliers who login to the eprocurement system available on PetroSA’s website. In exceptional circumstances, if you are registered on the PetroSA Supplier Database and you receive a request to tender or quote manually, please contact the PetroSA GSC Department to confirm that the request is legitimate. The PetroSA Group Supply Chain Department can be contacted by telephone and email available on the website (www.petrosa.co.za or www.procurement.petrosa.com). Kind Regards, Mr Comfort Bunting Group Supply Chain Manager PetroSA is the National Oil Company of South Africa. Formed in 2002 following the merger of Soekor E&P (Pty) Ltd and Mossgas (Pty) Ltd, PetroSA operates a Gas-to-Liquid (GTL) refinery in Mossel Bay and holds a portfolio of assets that spans the petroleum value chain. It upholds world-class safety and environmental standards, and trades oil and petrochemical products. Its GTL refinery produces ultra-clean, low-sulphur, low-aromatic synthetic fuels and high-value products converted from natural methane-rich gas and condensate using a unique Fischer Tropsch technology. -

Wrecking Ball

WRECKING BALL Why Permanent Technological Unemployment, a Predictable Pandemic and Other Wicked Problems Will End South Africa’s Experiment in Inclusive Democracy by Stu Woolman TERMS of USE This electronic version of the book is available exclusively on the NISC website for free download to use in research or private study. It may not be re-posted on book or other digital repositories that allow systematic sharing or download. For any commercial or other uses please contact the publishers, NISC (Pty) Ltd. Print copies of this book as well as e-Book versions available for online ordering from the African Books Collective and Amazon.com. © NISC (Pty) Ltd WRECKING BALL Why permanent technological unemployment, a predictable pandemic and other wicked problems will end South Africa’s experiment in inclusive democracy Wrecking Ball explores, in an unprecedented manner, a decalogue of wicked problems that confronts humanity: Nuclear proliferation, climate change, pandemics, permanent technological unemployment, Orwellian public and private surveillance, social media that distorts reality, cyberwarfare, the fragmentation of democracies, the inability of nations to cabin private power, the failure of multinational institutions to promote collaboration and the deepening of autocratic rule in countries that have never known anything but extractive institutions. Collectively, or even severally, these wicked problems constitute crises that could end civilisation. Does this list frighten you, or do you blithely assume that tomorrow will be just like yesterday? Wrecking Ball shows that without an inclusive system of global governance, the collective action required to solve those wicked problems falls beyond the remit of the world’s 20 inclusive democracies, 50 flawed democracies and 130 extractive, elitist autocracies. -

The Regulation of Commercial Petroleum Pipeline Operations: a South African Example

Corporate Ownership & Control / Volume 7, Issue 3, Spring 2010 – Continued – 1 THE REGULATION OF COMMERCIAL PETROLEUM PIPELINE OPERATIONS: A SOUTH AFRICAN EXAMPLE W J Pienaar* Abstract This paper provides an overview of a study of economic regulatory aspects of commercial petroleum pipeline operations. It addresses (1) the market structure, ownership patterns, and relative efficiency of petroleum pipeline transport; (2) pipeline operating costs; (3) proposed pricing principles. The research approach and methodology combine (1) a literature survey; (2) analysis of the cost structures of large commercial petroleum pipeline operators; and (3) interviews conducted with specialists in the petroleum refining and pipeline industries. The potential value of the research lies mainly in the developed guidelines for the economic regulation of market entry and pricing of the carriage of petroleum commodities by pipeline. Keywords: regulation, market entry, petroleum, pipeline *Stellenbosch University, Department of Logistics, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602, South Africa Tel: 27 21 808 2251, Fax: 27 21 808 3406 e-mail: [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION concluded upon: (1) market structure and ownership patterns; and (2) principles of efficient pricing. The commercial transportation of crude oil and The potential value of the research lies mainly in petroleum products by pipeline and envisaged new the economic regulatory framework and guidelines for investment in this mode of transport are receiving market entry and the pricing of the carriage of