South African Defence Industry Strategy 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa's Defence Industry: a Template for Middle Powers?

UNIVERSITYOFVIRGINIALIBRARY X006 128285 trategic & Defence Studies Centre WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY University of Virginia Libraries SDSC Working Papers Series Editor: Helen Hookey Published and distributed by: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Tel: 02 62438555 Fax: 02 624808 16 WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds National Library of Australia Cataloguirtg-in-Publication entry Mills, Greg. South Africa's defence industry : a template for middle powers? ISBN 0 7315 5409 4. 1. Weapons industry - South Africa. 2. South Africa - Defenses. I. Edmonds, Martin, 1939- . II. Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. III. Title. 338.4735580968 AL.D U W^7 no. 1$8 AUTHORS Dr Greg Mills and Dr Martin Edmonds are respectively the National Director of the South African Institute of Interna tional Affairs (SAIIA) based at Wits University, Johannesburg, South Africa, and Director: Centre for Defence and Interna tional Security Studies, Lancaster University in the UK. South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? 1 Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds Introduction The South African arms industry employs today around half of its peak of 120,000 in the 1980s. A number of major South African defence producers have been bought out by Western-based companies, while a pending priva tisation process could see the sale of the 'Big Five'2 of the South African industry. This much might be expected of a sector that has its contemporary origins in the apartheid period of enforced isolation and self-sufficiency. -

The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: an Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes

Comment The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: An Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes Raymond Paretzkyt Introduction With reports of violence and unrest in the Republic of South Africa a daily feature in American newspapers, public attention in the United States has increasingly focused on a variety of American efforts to bring an end to apartheid.. Little discussed in the ongoing debate over imposi- tion of new measures is the sanction that the United States has main- tained for the past twenty-three years: the South African arms embargo. How effective has this sanction been in denying South Africa access to items with military utility? Are there ways to strengthen the arms em- bargo so that it achieves greater success? An evaluation of the embargo is complicated by the fact that there is no one place in which the laws implementing it can be found. Rather, the relevant regulations have been incorporated into the existing, com- plex scheme of U.S. trade law. This article offers a complete account of the laws and regulations implementing the embargo, analyzes the defects in the regulatory scheme, and recommends ways to strengthen the em- bargo. The first part outlines the background of the imposition of the embargo, while the next three parts examine the regulations that govern American exports to South Africa and explore the loopholes in these reg- ulations that hinder their effectiveness. Part II discusses items on the t J.D. Candidate, Yale University. 1. Congress recently imposed various sanctions on South Africa. See Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, Pub. -

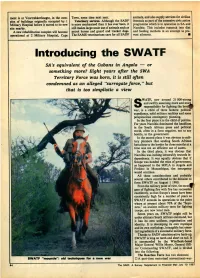

Introducing the SWATF

ment is at Voortrekkerhoogte, in the com Town, some time next year. animals, and also supply services for civilian plex of buildings originally occupied by 1 Veterinary services. Although the SADF livestock as part of the extensive civic action Military Hospital before it moved to its new is more mechanised than it has ever been, it programme which is in operation in SA and site nearby. still makes large-scale use of animals such as Namibia. This includes research into diet A new rehabilitation complex will become patrol horses and guard and tracker dogs. and feeding methods in an attempt to pre operational at 2 Military Hospital, Cape The SAMS veterinarians care for all SADF vent ailments. ■ Introducing the SWATF SA’s equivalent of the Cubans in Angola — or something more? Eight years after the SWA Territory Force was born, it is still often condemned as an alleged "surrogate force," but that is too simplistic a view WATF, now around 21 000-strong and swiftly assuming more and more S responsibility for fighting the bord(^ war, is a child of three fathers: political expediency, solid military realities and some perspicacious contingency planning. In the first place it is the child of politics. For years Namibia dominated the headlines in the South African press and political world, often in a form negative, not to say hostile, to the government. In the second place it was obvious to mili tary planners that sending South African battalions to the border for three months at a time was not an efficient use of assets. -

The Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Stephen Burgess and Helen Purkitt US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE ROLLBACK OF SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE PROGRAM by Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt April 2001 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm . Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Authors ............................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................v Chronology ................................................................................................vii I. Introduction .............................................................................................1 II. The Origins of the Chemical and Biological Warfare Program.............3 III. Project Coast, 1981-1993....................................................................17 IV. Rollback of Project Coast, 1988-1994................................................39 -

South African Defence Review 2012

CONSULTATIVE DRAFT PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 2 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT FOREWORD BY THE MINISTER Foreword: (L.N. SISULU) MINISTER OF DEFENCE AND MILITARY VETERANS CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 3 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 4 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT FOREWORD BY THE CHAIRPERSON Foreword: (R. MEYER) CHAIRPERSON OF THE DEFENCE REVIEW COMMITTEE CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 5 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 6 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE FOREWORD Minister of Defence Chairperson of the Defence Review Committee LIST OF FIGURES LIST OF ACRONYMS GLOSSARY OF TERMS (TO BE ADDED) 1 THE DEFENCE REVIEW Introduction Why a new Defence Review? What is the Defence Review? The Perennial Defence Dilemma Developing the Future Defence Policy Overarching Defence Principles 2 THE SOUTH AFRICAN STATE “A DEVELOPMENTAL PERSPECTIVE’ Introduction Form of Government and Legal System Political System Economic System Geography and Topography People and Society South Africa as a Democratic Developmental State Poverty Income Inequality Unemployment Education Criminality Defence and the Developmental State 3 THE STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT Introduction Global Security Trends International Relations, Balance of Power and Diplomacy CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Page 7 of 423 CONSULTATIVE DRAFT CHAPTER TITLE PAGE Inter-State Conflict and War Intra-State Conflict Global Competition for Strategic Resources Acts of Terror Weapons of Mass Destruction -

Tom Conrad, AFSC/NARMIC Tel

AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE 1501 Cherry Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 June 13, 1986 MEMORANDUM From: Tom Conrad, AFSC/NARMIC Tel. (215) 241-7004 . , Re: U.S. rugh-Tech Sales to South Afri.ca The United States is South Africa's top supplier of high-tech equipment. The United Nations arms embargo notwithstanding, U.S. companies ship millions of dollars of strategic goods to Pretoria every year ($185 million in computer hardware in 1984 alone; millions more in other high-tech sales). Despite the embargo, which bans shipments of "arms and related materiel," the U.S. government licenses the commercial export of a vast array of sensitive technology to Pretoria, including computers, electronics, electrooptics and communications equipment. Such shi ments should be sto ed to insure U.S. com liance with the United Nations arms embar o. T scan e one by strengt en lIg H.R. 868 t Ie Ant -Apart eid Act of 1986") which is currently before Congress. H.R. 4868 makes no reference to the arms embargo. While this bill is R step in the right direction, it will not stop U.S. strategic technology from reaching the practicioners of apartheid. How can the Anti-Apartheid Act be strengthened? 1. It should bar exports to South Africa of commodi.ti.es on the Munitions List • .. The Munitions List (Code of Federal Regulations, Title 22, pp. 323-327) identifies 21 categories of technology with explicit military applications. Current export controls continue to permit Munitions List items to be exported to South Africa (the Administration has licensed sales of navigation gear, image intensifiers and data encoding devices ostensibly destined for civilian applications). -

South Africa Missile Chronology

South Africa Missile Chronology 2007-1990 | 1989-1981 | 1980-1969 | 1968-1950 Last update: April 2005 As of May 28, 2009, this chronology is no longer being updated. For current developments, please see the South Africa Missile Overview. This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation 2007-1990 26 April 2007 The state-owned arms manufacturer Denel Group has signed a 1 billion rand (143 million U.S. dollars) deal with Brazil to co-develop a new generation missile. The missile will be the next-generation A-Darter, and air-to-air missile designed to meet future challenges of air combat fighters. The partnership will Brazil will bring "much needed skills, training and technology transfer to the country." Furthermore, future export contracts of another 2 billion rand are expected in the next 15 years. — "S. Africa, Brazil sign missile deal," People's Daily Online, 26 April 2007, english.people.com.cn. -

The Decline of South Africa's Defence Industry

Defense & Security Analysis ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cdan20 The decline of South Africa’s defence industry Ron Matthews & Collin Koh To cite this article: Ron Matthews & Collin Koh (2021): The decline of South Africa’s defence industry, Defense & Security Analysis, DOI: 10.1080/14751798.2021.1961070 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2021.1961070 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 08 Aug 2021. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cdan20 DEFENSE & SECURITY ANALYSIS https://doi.org/10.1080/14751798.2021.1961070 The decline of South Africa’s defence industry Ron Matthewsa and Collin Kohb aCranfield University, Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, Shrivenham, UK; bS. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The growth of South Africa’s apartheid era defence industry was South Africa; defence propelled by international isolation following the 1984 UN arms industry; arms exports; embargo and revealed military technology deficiencies during the corruption; offset border war. Weapons innovation became an imperative, fostering development of frontier technologies and upgrades of legacy platforms that drove expansion in arms exports. However, this golden era was not to last. The 1994 election of the country’s first democratic government switched resources from military to human security. The resultant defence-industrial stagnation continues to this day, exacerbated by corruption, unethical sales, and government mismanagement. -

South Africa's Strategic Arms Package: a Critical Analysis

52 SOUTH AFRICA’S STRATEGIC ARMS PACKAGE: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS Justin Sylvester and Prof Annette Seegers University of Cape Town Abstract The South African government’s Strategic Arms Package (SAP), has been the largest public controversy of the post-Apartheid era. We synthesise the debates about two dimensions of the SAP, military necessity and affordability, in order to get a better understanding of civil-military relations in democratic South Africa. Our synthesis shows that the economic enthusiasm about the SAP is both naïve and an opportunity for government and dominant business and industry to wed their interests in a way that is not that different from the Apartheid era. In military terms, the SAP has equipped the South African Air Force (SAAF) and South African Navy (SAN) for the most improbable of primary missions. The equipment is also not very relevant to secondary missions. The way that the SAP decisions were reached suggests that civil-military relations are marked by the continuing impact of past compromises, corruption and the centralisation of power in the executive branch. Introduction This article 1 presents a critical analysis of the South African government’s Strategic Arms Package (SAP), commonly known as the Arms Deal. 2 In 1999, the South African government (SAG) entered into an SAP of over R29 billion. At that stage, the SAP consisted of five main contracts. The German Submarine Consortium (GSC) was to supply four submarines to the SAN at a total cost of R4 289 million. The Italian company, Augusta, was awarded the right to supply 30 utility helicopters to the SAAF at R1 532 million. -

ACHIEVEMENTS of the SADF 1961 - 1982 Lt D Conradie*

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 13, Nr 2, 1983. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE SADF 1961 - 1982 Lt D Conradie* The founding of the Republic of South Africa in May 1961 had, according to International Law, no significant implications for existing international military agreements such as the Simonstown Agreement. However, with South Africa no longer a member of the Commonwealth, certain aspects did change, egothe erection of radar stations by the RSA in High Commission Territories had to be abandoned. The Arms Embargo - Spur for Self-sufficiency in Armament Just prior to South Africa becoming a republic, Establishment of the Armaments Board many African States insisted that the United Na- The changed attitude of the world towards the tions, and the Western countries should impose Republic of South Africa, and the United Nations an arms embargo on the Republic. Such an ap- Arms Embargo emphasized the need for arma- peal was made by the United Nations in August ment self-sufficiency. Until that stage the arma- 1963, and in June 1964 an Arms Embargo was ments procurement organisation, the Munitions instituted against the RSA. In November 1964 Production Office was a minor link in the RSA's the British Labour Government formally bound defence. It was quite clear that this organisation itself to uphold the arms boycott. would be inadequate for meeting the new chal- Although the arms embargo impeded South Afri- lenge. This situation led to the establishment of ca's armaments purchase programme, the the Armaments Board in terms of the Armaments SADF still succeeded in acquiring helicopters, Act, 1964. -

June 2021.Pdf

June 2021 VACCINE AIR LOGISTICS AIR VACCINE INTEGRATED REVIEW ON MARS FLYING HOW AVIATION COULD SLASH AVIATION ITS HOW ENVIRONMENTAL TOMORROW IMPACT RIGHT NOW? RIGHT HERE, HERE, RIGHT www.aerosociety.com AEROSPACE June 2021 Volume 48 Number 6 Royal Aeronautical Society AVAILABLE TO ALL MEMBERS Learn, develop and elevate with Aeroversity Introducing Aeroversity, our brand new integrated learning and professional development system, now exclusively available to all members. As a member of the Society, Aeroversity enables you to continue to develop your knowledge through informative courses, lecture videos and insightful podcasts along with specialist materials suited to your industry. Resources include: Webinars Lectures from our network of branches and divisions, available by video and podcast eLearning modules and courses eBooks library Advanced Technologies and Aerospace Database Briefing papers ..and much more! As a member of the Society, Aeroversity is the ideal place for you to record your initial and continuing professional development using MAPD - My Aero Professional Development. MAPD is a 2-way professional development platform, enabling members to access their CPD record and share with their mentors, colleagues and management for comments and feedback. Download the app or access via your desktop to explore the full range of resources available. Use your Society login to access here: www.aerosociety.com/aeroversity Volume 48 Number 6 June 2021 EDITORIAL Contents Grabbing the low-hanging Regulars 4 Radome 12 Transmission fruit The latest aviation and Your letters, emails, tweets aeronautical intelligence, and social media feedback. Faced with the immense challenge that is climate change and the seemingly analysis and comment. impossible goal of halting or slowing it, it is no wonder that some people throw 58 The Last Word 11 Pushing the Envelope Keith Hayward questions their hands up in despair that ‘nothing we can do can make a difference’. -

The South African Air Force, 1920–2012: a Review of Its History and an Indication of Its Cultural Heritage

222 Scientia Militaria vol 40, no 3, 2012, pp.222-249. doi: 10.5787/40-3-1043 The South African Air Force, 1920–2012: A Review of its History and an Indication of its Cultural Heritage André Wessels • Abstract Although a South African Aviation Corps existed for a few months in 1915, and although several South Africans saw action in World War I as members of Britain’s Royal Flying Corps, the history of the South African Air Force (SAAF) – the world’s second oldest air force – strictly speaking only dates back to 1 February 1920. In this article, a review is provided of the history of the SAAF, with specific reference to its operational deployments in the 1920s; the difficult years of the great depression and its aftermath and impact on the SAAF; the very important role played by the SAAF in the course of World War II (for example in patrolling South Africa’s coastal waters, and in taking part in the campaigns in East Africa and Abyssinia, as well as in North Africa, Madagascar, Italy, over the Mediterranean and in the Balkans); the post-war rationalisation; its small but important role in the Korean War; the acquisition of a large number of modern aircraft and helicopters from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s; the impact that sanctions had on the SAAF; the SAAF’s role in Northern Namibia and in Angola • Department of History, University of the Free State. Also a visiting fellow, University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy (UNSW@ADFA), Canberra.