Verb Form and Tense in Arabic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

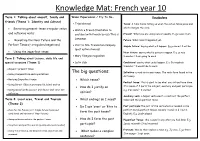

Knowledge Mat: French Year 10

Knowledge Mat: French year 10 Term 1: Talking about oneself, family and Wider Experiences / Try To Do… Vocabulary friends (Theme 1: Identity and Culture) • Trips abroad Tense: A time frame telling us when the action takes place and • Revisiting present tense irregular verbs which changes the verb. • Watch a French film/listen to and reflexive verbs youtube (with French lyrics)/This is Present: What you are doing now or usually. E.g je suis= I am Language • Revisiting the Near Future and the Future: What hasn’t happened yet. Perfect Tense (+ irregulars/negatives) • Visit to SDL Translation Company Simple future: Saying what will happen. Eg je serai= I will be (post option choices) • Using the imperfect tense Near future: saying what is going to happen. E.g. je vais • Mary Glasgow magazines travailler= I am going to work Term 2: Talking about Leisure, daily life and special occasions (Theme 1) • Latin club Conditional: saying what could happen. E.g. Je voudrais travailler= I would like to work • Depuis + present tense The big questions: Infinitive: a verb not in any tense. The verb form found in the • Using Comparatives and superlatives dictionary. • Revising Imperfect tense • Which tense? Perfect tense: This is used to say what you did and have done. • Using Direct Object pronouns (le,la,les) and en • How do I justify an It is made of 3 parts the subject, auxiliary and past participle. • Using modal verbs pouvoir and devoir and venir de+ e.g. J’ai visité – I visited opinion? infinitive Auxiliary verb: a helper verb used to construct the perfect Term 3: Local area, Travel and Tourism • What endings do I need? tense and the pluperfect tense (Theme 2) • Do I use ‘avoir’ or ‘être to Past participle:The part of the verb which is needed in the • perfect and pluperfect tenses. -

() Talking About Time

() Talking about Time 1I \ V 11) C I'{ Y ST!\ L Introduction When the heroes of Douglas Adams's The Hitch Hikers Guide to the Galaxy 1III'ivc at the location described in Part 2, The Restaurant at the End of the (1";IJerse (pp, 79-80), the narrator pauses for a moment of quiet reflection "hout the difficulties involved in travelling through time: The major problem is quite simply one of grammar, and the main work to consult in this matter is Dr Dan Streetmentioner's Time Travellers Handbook of 1001 Tense Formations. It will tell you for instance how to describe some• thing that was about to happen to you in the past before you avoided it by time-jumping forward two days in order to avoid it. The event will be described differently according to whether you are talking about it from the standpoint of your own natural time, from a time in the further future, or a time in the further past and is further complicated by the possibility of con• ducting conversations whilst you are actually travelling from one time to another with the intention of becoming your own mother or father. Most readers get as far as the Future Semi-Conditionally Modified Subinverted Plagal Past Subjunctive lntentional before giving up: and in fact in later editions of the book all the pages beyond this point have been left blank to save on printing costs. 17w Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy skips lightly over this tangle of aca• demic abstraction, pausing only to note that the term 'Future Perfect' has been abandoned since it was discovered not to be. -

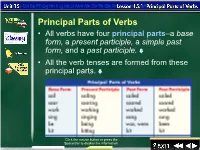

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

Corpus Study of Tense, Aspect, and Modality in Diglossic Speech in Cairene Arabic

CORPUS STUDY OF TENSE, ASPECT, AND MODALITY IN DIGLOSSIC SPEECH IN CAIRENE ARABIC BY OLA AHMED MOSHREF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Elabbas Benmamoun, Chair Professor Eyamba Bokamba Professor Rakesh M. Bhatt Assistant Professor Marina Terkourafi ABSTRACT Morpho-syntactic features of Modern Standard Arabic mix intricately with those of Egyptian Colloquial Arabic in ordinary speech. I study the lexical, phonological and syntactic features of verb phrase morphemes and constituents in different tenses, aspects, moods. A corpus of over 3000 phrases was collected from religious, political/economic and sports interviews on four Egyptian satellite TV channels. The computational analysis of the data shows that systematic and content morphemes from both varieties of Arabic combine in principled ways. Syntactic considerations play a critical role with regard to the frequency and direction of code-switching between the negative marker, subject, or complement on one hand and the verb on the other. Morph-syntactic constraints regulate different types of discourse but more formal topics may exhibit more mixing between Colloquial aspect or future markers and Standard verbs. ii To the One Arab Dream that will come true inshaa’ Allah! عربية أنا.. أميت دمها خري الدماء.. كما يقول أيب الشاعر العراقي: بدر شاكر السياب Arab I am.. My nation’s blood is the finest.. As my father says Iraqi Poet: Badr Shaker Elsayyab iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’m sincerely thankful to my advisor Prof. Elabbas Benmamoun, who during the six years of my study at UIUC was always kind, caring and supportive on the personal and academic levels. -

Arabic Verbs Made Easy with Effort

Arabic online for English Speakers Basic Arabic أسس by practice العربـيـةبالتطبيق Arabic Verbs Made Easy with Effort Ghalib Al-Hakkak Singular Dual Plural Past Present Past Present Past Present نـ ـــــــ ـــــــ نا نـ ـــــــ ـــــــ نا أ ـــــــ ـــــــت تـ ـــــــ ون ـــــــ تم تـ ـــــــ ان ـــــــ تـام تـ ـــــــ ـــــــت تـ ـــــــ ن ـــــــ تـن تـ ـــــــ ان ـــــــ تـام تـ ـــــــ يـن ـــــــت يـ ـــــــ ون ـــــــ وا يـ ـــــــ ان ـــــــ ا يـ ـــــــ ـــــــَ يـ ـــــــ ن ـــــــ ن تـ ـــــــ ان ـــــــ تا تـ ـــــــ ـــــــت Singular Dual Plural مجزوم منصوب مرفوع مجزوم منصوب مرفوع مجزوم منصوب مرفوع Same spelling Same spelling نكتب Same spelling Same spelling نكتب Same spelling Same spelling أكتب تكتبوا تكتبوا تكتبون تكتبا تكتبا تكتبان Same spelling Same spelling تكتب Same spelling Same spelling تكتبـن تكتبا تكتبا تكتبان تكتبي تكتبي تكتبيـن يكتبوا يكتبوا يكتبون يكتبا يكتبا يكتبان Same spelling Same spelling يكتب Same spelling Same spelling يكتبـن تكتبا تكتبا تكتبان Same spelling Same spelling تكتب Partial - for personnal use Arabic online for English Speakers http://www.al-hakkak.fr Basic Arabic أسس by practice العربـيـةبالتطبيق Arabic Verbs Made Easy with Effort Version 1.4 Tables, exercises, corrections and index Textbook with online recordings Ghalib Al-Hakkak © Ghalib Al-Hakkak, Self published author - France ( [email protected] ) 1 Partial - for personnal use © Ghalib Al-Hakkak, August 2016 ISBN-13: 978-1536813913 / ISBN-10: 1536813915 Author : Ghalib AL-HAKKAK, Marmagne 71710, Burgandy, France Publisher : Ghalib AL-HAKKAK, Self published author (auteur auto-édité) Printed by and distributed through : Amazon Website : www.al-hakkak.fr Email : [email protected] 2 Partial - for personnal use Introduction It is important for an English speaker to choose the most suitable way to learn Arabic verbs. -

Inflectional Morphology in Arabic and English: a Contrastive Study

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 5, No. 2; 2015 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Inflectional Morphology in Arabic and English: A Contrastive Study Muayad Abdul-Halim Ahmad Shamsan1,2 & Abdul-majeed Attayib3 1 College of Science and Arts, University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia 2 Faculty of Arts, Omdurman Islamic University, Sudan 3 English Language Centre, Umm AlQura University, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Muayad Abdul-Halim Ahmad Shamsan, M. A Lecturer, College of Science and Arts, University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 14, 2015 Accepted: February 12, 2015 Online Published: March 29, 2015 doi:10.5539/ijel.v5n2p139 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v5n2p139 Abstract This paper investigates Arabic and English inflectional morphology with a view to identifying the similarities and differences between them. The differences between the two languages might be the main reason for making errors by Arab EFL learners. Predicting the sources of such errors might help both teachers and learners to overcome these problems. By identifying the morphological differences between the two languages, teachers will determine how and what to teach, on the one hand, and students will know how and what to focus on when learning the target language, on the other. Keywords: inflectional morphology, modern standard Arabic, contrastive analysis 1. Introduction 1.1 Inflectional Morphology Inflectional affixes are those which are affixed to words to indicate grammatical function. Spencer, (1991, p. 21) points out “Inflectional operations leave untouched the syntactic category of the base, but they too add extra elements. -

The Lexical Semantics of the Arabic Verb OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 28/2/2018, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 28/2/2018, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 28/2/2018, SPi The Lexical Semantics of the Arabic Verb OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 28/2/2018, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 28/2/2018, SPi The Lexical Semantics of the Arabic Verb PETER JOHN GLANVILLE 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 28/2/2018, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, , United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Peter John Glanville The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Madison Avenue, New York, NY , United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: ISBN –––– (hbk.) –––– (pbk.) Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Arabic and English Verb Systems Using the Qur’An Arabic Corpus

A Comparative Analysis of The Arabic and English Verb Systems Using the Qur’an Arabic Corpus A corpus-based study Jawharah Saeed Alasmari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Languages May, 2020 I The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Jawharah Alasmari to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2020 The University of Leeds and Jawharah Saeed Alasmari II Publication Chapters two, three, and five of this thesis are based on the following jointly-authored publications. The candidate is the principal author of all original contributions presented in these papers, the co-authors acted in an advisory capacity, providing feedback, general guidance and comments. Alasmari, J., Watson, J. C. E., and Atwell E. (2018). A Contrastive Study of the Arabic and English Verb Tense and Aspect A Corpus-Based Approach. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), pp. 1604-1615. Alasmari, J., Watson J. C.E., and Atwell, E. (2017). A comparative analysis of verb tense and aspect in Arabic and English using Google Translate. International Journal on Islamic Applications in Computer Science and Technology, 5(3), pp. 9-14. -

Language and Communication Enhancement for Two-Way Education : Report

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Pre. 2011 1995 Language and communication enhancement for two-way education : Report Ian G. Malcolm Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Malcolm, I. (1995). Language and communication enhancement for two-way education : report. Perth, Australia: Edith Cowan Uinversity. This Report is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/7174 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Aspect-Marking Basic Verbs in Arabic Dana Abdulrahim University of Alberta

Polyfunctionality: Basic Verbs Monday 24 June / 16:30-16:55 / CCIS L1-140 Aspect-marking Basic Verbs in Arabic Dana Abdulrahim University of Alberta Cognitive approaches to language assert that our earliest, primary bodily experiences with the world play a very crucial role in shaping linguistic structures (Lakoff, 1987). Basic Verbs, or lexical items encoding basic bodily events and states, such as COME, GO, SIT, STAND, LIE, EAT, DRINK, TAKE, GIVE, etc. (Newman, 2004), show a proliferation of uses across languages ranging from polysemous and idiomatic uses to patterns of grammaticalization and collocation. Cross-linguistically, verbs denoting GO, for instance, can assume numerous grammatical functions such as marking future tense, habitual and progressive aspects, purpose and change-of-state, etc. (Heine and Kuteva, 2002). A great deal of research has been dedicated to the investigation of the properties as well as uses of Basic Verbs in several languages, such as GO and COME (e.g. Fillmore, 1966; Radden, 1996; to name but a few), EAT and DRINK (Newman and Rice, 2006), SIT, STAND, and LIE (Newman and Rice, 2004), and GIVE (e.g. Newman, 1996). While the existing body of cross-linguistic research on Basic Verbs is growing, there is relatively little research that has been done on the variations in functions and behavior of Basic Verbs across standard and spoken varieties of Arabic. This paper will discuss the lexico-syntactic properties of certain Basic Verbs in Arabic – more specifically, aspect-marking Basic Verbs – in standard and some non-standard varieties of Arabic. An online MSA corpus (www.arabicorpus.byu.edu) and a spoken corpus constructed by the author will be the main source for contextualized verb uses. -

Cultural and Linguistic Guidelines for Language Evaluation of Arab-American

Cultural and linguistic guidelines for language evaluation of Arab-American children using the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF) Reference this material as: Khamis-Dakwar,R., Al-Askary,H., Benmamoun,A., Ouali,H., Green,H., Leung,T., & Al-Asbahi,K. (2012, September 30). Cultural and linguistic guidelines for language evaluation of Arab-American children using the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals (CELF).Available from doi:xxxxx Copyright © 2012 Reem Khamis-Dakwar. All rights reserved Part I: The Cultural and Linguistic Background of Arab-Americans Introduction Based on the 2000 census, Arab Americans comprise 0.42% of the population in the United States (U.S.). The Arab-American population in the United States has been showing a steady increase since the 1980s (US. Bureau of the Census, 2005)1. Similar to other minority populations in the U.S., there has been a corresponding increase in the number of children referred for language assessment from this specific cultural and linguistic background. It is one of the top ten languages among English Language Learners (LLEs) in the U.S. (Batalova & Margie, 2010). Arab-Americans, as part of the diverse Arab population, compose a heterogeneous group; they come to the U.S. from countries in the North African region (such as Morocco), the Mediterranean region (such as Jordan), or the Arab Gulf region (such as Qatar) (Al-Hazza & Lucking, 2005) and may belong to a variety of religious faiths such as Islam, Christianity, Druze or Judaism. Despite these differences, Arab- Americans share historical memories, cultural values, cultural practices and Arabic as a native language 2(Khamis-Dakwar & Froud, 2012). -

Stative and Stativizing Constructions in Arabic News Reports: a Corpus-Based Study Written by Aous Mansouri Has Been Approved for the Department of Linguistics

Stative and Stativizing Constructions in Arabic News Reports: A Corpus-Based Study by Aous Mansouri M.B.B.S., King Saud University, 1999 M.A. University of Colorado, 2005 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics 2016 This thesis entitled: Stative and Stativizing Constructions in Arabic News Reports: A Corpus-Based Study written by Aous Mansouri has been approved for the Department of Linguistics Dr. Laura Michaelis-Cummings Dr. Martha Palmer Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. !ii Mansouri, Aous A. (Ph.D., Linguistics) Stative and Stativizing Constructions in Arabic News Reports: A Corpus-Based Study Thesis directed by Dr. Laura A. Michaelis This dissertation uses a corpus of tokens retrieved from broadcast news stories and print news articles to examine the array of constructions used to encode stative predications in Modern Standard Arabic. A state is defined as a situation that includes its reference time, whether that time is encoding time or another time of orientation. A range of stativity diagnostics are implemented. The constructions analyzed include both those that select for the class of states and those that yield various stative construals of otherwise dynamic predications. The constructions examined range from inflectional constructions to verb-headed phrasal patterns to verbless predicates; a lexicalist implementation of Construction Grammar, Sign Based Construction Grammar, provides a uniform format for representing the constructions as feature-structure descriptions.