Language and Communication Enhancement for Two-Way Education : Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

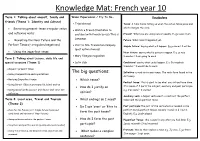

Knowledge Mat: French Year 10

Knowledge Mat: French year 10 Term 1: Talking about oneself, family and Wider Experiences / Try To Do… Vocabulary friends (Theme 1: Identity and Culture) • Trips abroad Tense: A time frame telling us when the action takes place and • Revisiting present tense irregular verbs which changes the verb. • Watch a French film/listen to and reflexive verbs youtube (with French lyrics)/This is Present: What you are doing now or usually. E.g je suis= I am Language • Revisiting the Near Future and the Future: What hasn’t happened yet. Perfect Tense (+ irregulars/negatives) • Visit to SDL Translation Company Simple future: Saying what will happen. Eg je serai= I will be (post option choices) • Using the imperfect tense Near future: saying what is going to happen. E.g. je vais • Mary Glasgow magazines travailler= I am going to work Term 2: Talking about Leisure, daily life and special occasions (Theme 1) • Latin club Conditional: saying what could happen. E.g. Je voudrais travailler= I would like to work • Depuis + present tense The big questions: Infinitive: a verb not in any tense. The verb form found in the • Using Comparatives and superlatives dictionary. • Revising Imperfect tense • Which tense? Perfect tense: This is used to say what you did and have done. • Using Direct Object pronouns (le,la,les) and en • How do I justify an It is made of 3 parts the subject, auxiliary and past participle. • Using modal verbs pouvoir and devoir and venir de+ e.g. J’ai visité – I visited opinion? infinitive Auxiliary verb: a helper verb used to construct the perfect Term 3: Local area, Travel and Tourism • What endings do I need? tense and the pluperfect tense (Theme 2) • Do I use ‘avoir’ or ‘être to Past participle:The part of the verb which is needed in the • perfect and pluperfect tenses. -

() Talking About Time

() Talking about Time 1I \ V 11) C I'{ Y ST!\ L Introduction When the heroes of Douglas Adams's The Hitch Hikers Guide to the Galaxy 1III'ivc at the location described in Part 2, The Restaurant at the End of the (1";IJerse (pp, 79-80), the narrator pauses for a moment of quiet reflection "hout the difficulties involved in travelling through time: The major problem is quite simply one of grammar, and the main work to consult in this matter is Dr Dan Streetmentioner's Time Travellers Handbook of 1001 Tense Formations. It will tell you for instance how to describe some• thing that was about to happen to you in the past before you avoided it by time-jumping forward two days in order to avoid it. The event will be described differently according to whether you are talking about it from the standpoint of your own natural time, from a time in the further future, or a time in the further past and is further complicated by the possibility of con• ducting conversations whilst you are actually travelling from one time to another with the intention of becoming your own mother or father. Most readers get as far as the Future Semi-Conditionally Modified Subinverted Plagal Past Subjunctive lntentional before giving up: and in fact in later editions of the book all the pages beyond this point have been left blank to save on printing costs. 17w Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy skips lightly over this tangle of aca• demic abstraction, pausing only to note that the term 'Future Perfect' has been abandoned since it was discovered not to be. -

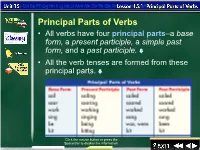

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

Department Long Term Plans September 2020

Department long term plans September 2020 LONG TERM CURRICULUM PLANNING OVERVIEW: MODERN FOREIGN LANGUAGES YEAR 7 YEAR 8 YEAR 9 YEAR 10 YEAR 11 Autumn A Bienvenue! (Basic language My Teenage Life (TV, film, My Social Life (social media, Myself, My Family, My friends Global and Social Issues Knowledge formation and skills) cinema, weather and relationships, describing (Relationships with family) (environment and charity / Colours, pets, family and activities in the past) dates, describing a music Home Town, Neighbourhood voluntary work) classroom language festival) and Region (where I live) Autumn A Developing understanding of Understanding and using Frequencies, adjectives and Understand and Use direct Using modal verbs linked to Skills common verbs, nouns and subject pronouns from 1st – verbs. object pronouns behaviours (must do/can basic information 3rd person. Recognising and Using direct Use reflexive verbs do/should do/could do etc) Using “never” as a negative object pronouns. Use comparatives, Using conditional tense and form. Using the near future for superlatives and the comparatives for effects of Opinions and longer invitations. conditional tense behaviours on environment descriptions / narrations. Using the perfect (past) Interrogative structures using Manipulating si sentences Using “when” and “if” with tense. all three tenses revised for outlining activities and weather. Narrations and personal consequences of actions Recognising and using the opinions Recognising and using perfect tense with -er verbs. Prepositions pluperfect -

A Case for 'Be Going To' As Prospective Aspect

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2011 A Case for 'be going to' as Prospective Aspect Sara E. Schroeder The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Schroeder, Sara E., "A Case for 'be going to' as Prospective Aspect" (2011). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 21. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Case for be going to as Prospective Aspect By SARA ELIZABETH SCHROEDER Bachelor of Arts in Classical Studies and History, Loras College, Dubuque, Iowa 2004 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2011 Approved by: Perry Brown, Associate Provost for Graduate Education Graduate School Dr. Leora Bar-el Linguistics Dr. Tully Thibeau Linguistics Dr. Irene Appelbaum Linguistics Schroeder, Sara, M.A. in Linguistics, Spring 2011 Linguistics A Case For be going to as Prospective Aspect Chairperson: Dr. Leora Bar-el The focus of this thesis is the feature of current relevance as it is expressed by the English present perfect and the present be going to construction. -

'Graded Tense' in Gĩkũyũ

Beyond the Past, Present and Future: Towards the Semantics of ‘Graded Tense’ in Gĩkũyũ Seth Cable University of Massachusetts Amherst ABSTRACT: In recent years, our understanding of how tense systems vary across languages has been greatly advanced by formal semantic study of languages exhibiting fewer tense categories than the three commonly found in European languages (Bohnemeyer 2002, Lin 2006, Matthewson 2006, Jóhannsdóttir & Matthewson 2007, Tonhauser 2011). However, it has also often been reported that languages can sometimes distinguish more than three tenses (Comrie 1985, Dahl 1985, Bybee et al. 1994). Such languages appear to have ‘graded tense’ systems, where the tense morphology serves to track how far into the past or future a reported event occurs. This paper presents a formal semantic analysis of the tense- aspect system of Gĩkũyu ̃ (Kikuyu), a Northeastern Bantu language of Kenya. Like many languages of the Bantu family, Gĩkũyu ̃ appears to exhibit a graded tense system, wherein four grades of past tense and three grades of future tense are distinguished. However, I argue that the prefixes traditionally labeled as ‘tenses’ in Gĩkũyu ̃ exhibit important differences from (and similarities to) tenses in languages like English. I will defend the hypothesis that, like tenses in English, these ‘temporal remoteness prefixes’ in Gĩkũyũ introduce presuppositions regarding a temporal parameter of the clause. However, unlike English tenses, these presuppositions concern the ‘Event Time’ of the clause directly, and not the ‘Topic Time’. Consequently, the key difference between Gĩkũyu ̃ and languages like English lies not in how many tenses are distinguished, but in whether tense-like features are able to modify other, lower verbal functional projections in the clause. -

Spanish Learning Journey

Spanish Curriculum Learning Journey Knowledge & Concepts increase students depth/ challenge and build on previous learning where topics are revisted throughout their learning journey Year 7 Year 8 Year 9 Year 10 Year 11 Year 12 Year 13 Monarchies, Self, Family, Family and Home Me, my family and Celebrations Local, national and dictatorships Topics The Internet Friends Life friends Festivals global issues and popular movements Recap key questions 1) Positive and/or (name, nationality, Comparing myself, modal verbs linked negative influence of Imperfect (past Introductions, where I live) others. Adjectival to behaviours (e.g the Internet Subjunctive continuous) vs phonetics, numbers agreement. must do/can tense ( Preterite (perfect + alphabet, months / do/should do/could and smart phones comparatives más tense) Using a sequence dates, age, adjectives do etc) of personality Describing others, que/menos que of tenses comparisons + (more/less than) Half superlatives 2) Consider the type Revise Preterite To be & To go (Ser & Term Grammar: tener (to (“if”) si sentences of influence social & imperfect 1st -3rd person: To be Ir) in preterite tense networks have on subjunctive 1 have), ser and estar revised for outlining Knowledge (Ser / Estar) (to be) present tense consequences of society describe family ordinal numbers action (Future tense) 1st – 3rd person (I, (physically) + family Possessive adjectives (1st, 2nd, 3rd etc) relationships, daily Cognates (words that you, he/she): To have (Tener) activities Reflexive verbs: to are similar in Spanish Present and present to english) marry, to get Pluperfect tense: continuous tense. Comprehension annoyed with, to get “had done practice and on well with something” To be (Both Ser and Adjectival agreement casarse/enfadarse/ll techniques Estar) 1-3rd person quantity words Comparatives and evarse bien con mucho, demasiado, superlatives. -

Verbs/Verb Tenses

MPC English & Study Skills Center Verbs/Verb Tenses Verbs in a sentence supply the actions that are happening and give a sense of the time frame in which those actions occur. There are about thirty verb tenses in English, but this handout discusses the basic twelve tenses in the active voice (subject is doing the action) and also briefly discusses those tenses in the passive voice (subject is receiving the action), as well as some other verb forms, such as modal and phrasal verbs. A sentence may have one single verb or a combination of verb forms. Verb tenses are grouped into four major categories, based on the period of time over which the action takes place: simple, progressive, perfect, and perfect progressive. Each group, in turn, has three different times the action can happen: present, past, and future. Verb Forms There are two basic types of verbs (regular and irregular) and five forms that each type can take. An exception is the verb be, which is highly irregular and has eight forms: be, am, are, is, was, were, been, and being. Regular verbs: All make the past tense by adding –d or -ed: walked, hurried, talked, worked, etc. Present Present Past Past Participle S-form (Base Form) Participle talk talked talked talking talks help helped helped helping helps Irregular verbs: All make the past tense in a variety of ways: ran, bought, taught, drove, ate, etc. Present Present Past Past Participle S-form (Base Form) Participle give gave given giving gives eat ate eaten eating eats The present participle and past participle do not act as verbs without a helping or auxiliary verb. -

Time and Tense in Language Events and Relations Tense

Time and Tense in Language Events and Relations Event expressions; tensed verbs; has left, was captured, will resign; James Pustejovsky stative adjectives; sunken, stalled, on board; event nominals; merger, Military Operation, Gulf Brandeis University War; Dependencies between events and times: Anchoring; John left on Monday. LING 130 Orderings; The party happened after midnight. Embedding; John said Mary left. FALL, 2005 Tense Reichenbach • Tensed utterances introduce references to 3 ‘time points’ – Speech Time: S • Grammatical expression of the time of – Event Time: E the situation described, relative to some – Reference Time: R other time (e.g., moment of speech) SI had [mailed the letter]E [when John came & told me the news]R E < R < S E R S time • The concept of ‘time point’ is an abstraction –- it can map to an interval • Three temporal relations are defined on these time points PAST PRESENT FUTURE – at, before, after • 13 different relations are possible George admires Adolf. George admired Jesus. Tense as Anaphor: Reichenbach Reichenbachian Tense Analysis • Tensed utterances introduce references to 3 ‘time points’ • Tense is determined by – Speech Time: S Relation Reichenbach’s English Tense Example relation between R and S – Event Time: E Tense Name Name – R=S, R<S, R>S E<R<S Anterior past Past perfect I had slept • Aspect is determined by – Reference Time: R E=R<S Simple past Simple past I slept R<E<S relation between E and R I had [mailed the letter] [when John came & told me the news] R<S=E Posterior past I would – E=R, E < -

Earlier Works on Tense and Aspect in Manipuri (Meeteilon)

=================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.comISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 16:10 October 2016 =================================================================== Earlier Works on Tense and Aspect in Manipuri (Meeteilon) Ningombam Sanatombi Devi, M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D. Research Scholar ================================================================== Abstract Meeteilon is a tenseless language. But the traditional grammarians like KalachandShastri, Nandalal Sharma and Dwijamani Dev claimed that Meeteilon has tense that each Present, Past and Future is further analyzed into four units: Indefinite, Continuous, Perfect and Perfect Continuous. They analysed the language on the framework of Sanskrit and English languages. This claim is challenged by modern linguists like Bhat and Ningomba (1997) and Madhubala (1979). They observed that Meeteilon shows two tense distinctions as future and non-future (both past and present). This claim is further challenged by linguists like Thoudam (1991) and Mahabir (1988) arguing that Manipuri verbs are not morphologically marked by tense. Thoudam (1988) observes that the tense system found in Greek, Sanskrit, Latin, etc., is not found in Manipuri language. Tense, in this language, is shown by adverbial time element, not by morphological markers on the verb. Keywords: Meeteilon, Tense, Aspect, Past, Present, Future. Introduction In this paper, I will present a brief review on the earlier works of tense and aspect by KalachandShastri (1971), M.S.Ningomba (1992), Nandalal Sharma (1976), P.C.Thoudam (1991), Singh (2000), Chelliah (1997), D.N.S Bhatt and M.S. Ningomba (1997) and observed their different opinions. This work mainly involved translating their books which were written in Bengali script into English. 1. KalachandShastri (1971) Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 16:10 October 2016 Ningombam Sanatombi Devi, M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D. -

Verb Form and Tense in Arabic

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 10, No. 5; 2020 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Verb Form and Tense in Arabic Yasir Alotaibi1 1 Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Dr. Yasir Alotaibi, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 19, 2020 Accepted: July 26, 2020 Online Published: July 30, 2020 doi:10.5539/ijel.v10n5p284 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v10n5p284 Abstract This paper discusses tense in Arabic based on three varieties of the language: Classical Arabic (CA), Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), and the Taif dialect (TD). We argue against previous analyses that suggest that Arabic is a tenseless language, which assume that tense information is derived from the context. We also argue against the suggestion that Arabic is tensed, but that its tense is relative, rather than absolute. We propose here that CA, MSA, and TD have closely related verb forms, and that these are tensed verbs. Tense in Arabic is absolute in a neutral context and verb forms take the perfective and imperfective aspect. Similar to other languages including English, verb forms in Arabic may take reference from the context instead of the present moment. In this case, we argue that this does not mean that tense in Arabic is relative, because this would also imply that tense in many languages, including English, is relative. Further, we argue that the perfective form indicates only the past tense and the imperfective form, only the present; all other interpretations are derived by implicature. -

23 Tense and Aspect: Discussion and Conclusions

23 Tense and Aspect: Discussion and Conclusions John Hewson 23.1 Introduction Because much original work was done on questions of Tense and Aspect in the last fifty years, it is important to start with a brief discussion on current terminology in Tense-Aspect studies. Linguists have in recent years used the generic terms Completive and Incompletive (see Comrie 1976:18-21and 44-48 for discussion of completion ) to cover a range of different sub-categories, both Lexical (L) and Grammatical (G), as in (1). (1) Completive Imcompletive a. L. Achievements L. Activities (give, tell, put) (walk, say, think) b. G. Perfective G. Imperfective (spoken, gone) (speaking, going) c. G. Nonprogressive G. Progressive (I spoke, I went) (I was speaking, I was going) 1. The lexical terms in (1a) are those used by Vendler (1967:97-121), and much discussed since, along with such terms as Achievements and States . The interplay between lexical aspect (sometimes called Aktionsart) and grammatical aspect is an important part of TA studies, and acknowledged by all the principal writers in the field.. 2. The English Perfectives and Imperfectives in (1b) are non-finite forms (participles), as used in the Auctioneer’s “Going..., Going..., Gone! The finite forms (1c), in contrast to the non-finite forms in (1b), are Progressive and “Nonprogressive”. 3. The term Nonprogressive is used by Comrie (1976:25), but has been criticized by others, e.g. Bybee et al. 1994:138, who note that “Nonprogressive is not defined”, and prefer to use the term Perfective instead. 4. There are, however, major differences in patterns of usage and distribution between Perfective and “Nonprogressive”, just as there are between Imperfective and Progressive: a “Nonprogressive” is demonstrably not a Perfective.