Future Tense, Prospective Aspect, and Irrealis Mood As Part of the Situation Perspective: Insights from Basque, Turkish, and Papuan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knowledge Mat: French Year 10

Knowledge Mat: French year 10 Term 1: Talking about oneself, family and Wider Experiences / Try To Do… Vocabulary friends (Theme 1: Identity and Culture) • Trips abroad Tense: A time frame telling us when the action takes place and • Revisiting present tense irregular verbs which changes the verb. • Watch a French film/listen to and reflexive verbs youtube (with French lyrics)/This is Present: What you are doing now or usually. E.g je suis= I am Language • Revisiting the Near Future and the Future: What hasn’t happened yet. Perfect Tense (+ irregulars/negatives) • Visit to SDL Translation Company Simple future: Saying what will happen. Eg je serai= I will be (post option choices) • Using the imperfect tense Near future: saying what is going to happen. E.g. je vais • Mary Glasgow magazines travailler= I am going to work Term 2: Talking about Leisure, daily life and special occasions (Theme 1) • Latin club Conditional: saying what could happen. E.g. Je voudrais travailler= I would like to work • Depuis + present tense The big questions: Infinitive: a verb not in any tense. The verb form found in the • Using Comparatives and superlatives dictionary. • Revising Imperfect tense • Which tense? Perfect tense: This is used to say what you did and have done. • Using Direct Object pronouns (le,la,les) and en • How do I justify an It is made of 3 parts the subject, auxiliary and past participle. • Using modal verbs pouvoir and devoir and venir de+ e.g. J’ai visité – I visited opinion? infinitive Auxiliary verb: a helper verb used to construct the perfect Term 3: Local area, Travel and Tourism • What endings do I need? tense and the pluperfect tense (Theme 2) • Do I use ‘avoir’ or ‘être to Past participle:The part of the verb which is needed in the • perfect and pluperfect tenses. -

() Talking About Time

() Talking about Time 1I \ V 11) C I'{ Y ST!\ L Introduction When the heroes of Douglas Adams's The Hitch Hikers Guide to the Galaxy 1III'ivc at the location described in Part 2, The Restaurant at the End of the (1";IJerse (pp, 79-80), the narrator pauses for a moment of quiet reflection "hout the difficulties involved in travelling through time: The major problem is quite simply one of grammar, and the main work to consult in this matter is Dr Dan Streetmentioner's Time Travellers Handbook of 1001 Tense Formations. It will tell you for instance how to describe some• thing that was about to happen to you in the past before you avoided it by time-jumping forward two days in order to avoid it. The event will be described differently according to whether you are talking about it from the standpoint of your own natural time, from a time in the further future, or a time in the further past and is further complicated by the possibility of con• ducting conversations whilst you are actually travelling from one time to another with the intention of becoming your own mother or father. Most readers get as far as the Future Semi-Conditionally Modified Subinverted Plagal Past Subjunctive lntentional before giving up: and in fact in later editions of the book all the pages beyond this point have been left blank to save on printing costs. 17w Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy skips lightly over this tangle of aca• demic abstraction, pausing only to note that the term 'Future Perfect' has been abandoned since it was discovered not to be. -

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

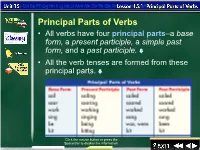

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Aktionsart and Aspect in Qiang

The 2005 International Course and Conference on RRG, Academia Sinica, Taipei, June 26-30 AKTIONSART AND ASPECT IN QIANG Huang Chenglong Institute of Ethnology & Anthropology Chinese Academy of Social Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Qiang language reflects a basic Aktionsart dichotomy in the classification of stative and active verbs, the form of verbs directly reflects the elements of the lexical decomposition. Generally, State or activity is the basic form of the verb, which becomes an achievement or accomplishment when it takes a directional prefix, and becomes a causative achievement or causative accomplishment when it takes the causative suffix. It shows that grammatical aspect and Aktionsart seem to play much of a systematic role. Semantically, on the one hand, there is a clear-cut boundary between states and activities, but morphologically, however, there is no distinction between them. Both of them take the same marking to encode lexical aspect (Aktionsart), and grammatical aspect does not entirely correspond with lexical aspect. 1.0. Introduction The Ronghong variety of Qiang is spoken in Yadu Township (雅都鄉), Mao County (茂縣), Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture (阿壩藏族羌族自治州), Sichuan Province (四川省), China. It has more than 3,000 speakers. The Ronghong variety of Qiang belongs to the Yadu subdialect (雅都土語) of the Northern dialect of Qiang (羌語北部方言). It is mutually intelligible with other subdialects within the Northern dialect, but mutually unintelligible with other subdialects within the Southern dialect. In this paper we use Aktionsart and lexical decomposition, as developed by Van Valin and LaPolla (1997, Ch. 3 and Ch. 4), to discuss lexical aspect, grammatical aspect and the relationship between them in Qiang. -

Corpus Study of Tense, Aspect, and Modality in Diglossic Speech in Cairene Arabic

CORPUS STUDY OF TENSE, ASPECT, AND MODALITY IN DIGLOSSIC SPEECH IN CAIRENE ARABIC BY OLA AHMED MOSHREF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Elabbas Benmamoun, Chair Professor Eyamba Bokamba Professor Rakesh M. Bhatt Assistant Professor Marina Terkourafi ABSTRACT Morpho-syntactic features of Modern Standard Arabic mix intricately with those of Egyptian Colloquial Arabic in ordinary speech. I study the lexical, phonological and syntactic features of verb phrase morphemes and constituents in different tenses, aspects, moods. A corpus of over 3000 phrases was collected from religious, political/economic and sports interviews on four Egyptian satellite TV channels. The computational analysis of the data shows that systematic and content morphemes from both varieties of Arabic combine in principled ways. Syntactic considerations play a critical role with regard to the frequency and direction of code-switching between the negative marker, subject, or complement on one hand and the verb on the other. Morph-syntactic constraints regulate different types of discourse but more formal topics may exhibit more mixing between Colloquial aspect or future markers and Standard verbs. ii To the One Arab Dream that will come true inshaa’ Allah! عربية أنا.. أميت دمها خري الدماء.. كما يقول أيب الشاعر العراقي: بدر شاكر السياب Arab I am.. My nation’s blood is the finest.. As my father says Iraqi Poet: Badr Shaker Elsayyab iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’m sincerely thankful to my advisor Prof. Elabbas Benmamoun, who during the six years of my study at UIUC was always kind, caring and supportive on the personal and academic levels. -

The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor

THE GRAMMAR OF FEAR: MORPHOSYNTACTIC METAPHOR IN FEAR CONSTRUCTIONS by HOLLY A. LAKEY A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Holly A. Lakey Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Linguistics by: Dr. Cynthia Vakareliyska Chairperson Dr. Scott DeLancey Core Member Dr. Eric Pederson Core Member Dr. Zhuo Jing-Schmidt Institutional Representative and Dr. Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2016. ii © 2016 Holly A. Lakey iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Holly A. Lakey Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics March 2016 Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This analysis explores the reflection of semantic features of emotion verbs that are metaphorized on the morphosyntactic level in constructions that express these emotions. This dissertation shows how the avoidance or distancing response to fear is mirrored in the morphosyntax of fear constructions (FCs) in certain Indo-European languages through the use of non-canonical grammatical markers. This analysis looks at both simple FCs consisting of a single clause and complex FCs, which feature a subordinate clause that acts as a complement to the fear verb in the main clause. In simple FCs in some highly-inflected Indo-European languages, the complement of the fear verb (which represents the fear source) is case-marked not accusative but genitive (Baltic and Slavic languages, Sanskrit, Anglo-Saxon) or ablative (Armenian, Sanskrit, Old Persian). -

Shǐxīng, a Sino-Tibetan Language

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 32.1 — April 2009 , A SINO-TIBETAN LANGUAGE OF SOUTH-WEST CHINA: SHǏXĪNG ∗ A GRAMMATICAL SKETCH WITH TWO APPENDED TEXTS Katia Chirkova Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l’Asie Orientale, CNRS Abstract: This article is a brief grammatical sketch of Shǐxīng, accompanied by two analyzed and annotated texts. Shǐxīng is a little studied Sino-Tibetan language of South-West China, currently classified as belonging to the Qiangic subgroup of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Based on newly collected data, this grammatical sketch is deemed as an enlarged and elaborated version of Huáng & Rénzēng’s (1991) outline of Shǐxīng, with an aim to put forward a new description of Shǐxīng in a language that makes it accessible also to a non-Chinese speaking audience. Keywords: Shǐxīng; Qiangic; Mùlǐ 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Location, name, people The Shǐxīng 史兴语 language is spoken by approximately 1,800 people who reside along the banks of the Shuǐluò 水洛 river in Shuǐluò Township of Mùlǐ Tibetan Autonomous County (WT smi li rang skyong rdzong). This county is part of Liángshān Yí Autonomous Prefecture in Sìchuān Province in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Shuǐluò Township, where the Shǐxīng language is spoken, is situated in the western part of Mùlǐ (WT, variously, smi li, rmi li, mu li or mu le). Mùlǐ is a mountainous and forested region of 13,246.38 m2 at an average altitude of 3,000 meters above sea level. Before the establishment of the PRC in 1949, Mùlǐ was a semi-independent theocratic kingdom, ruled by hereditary lama kings. -

Humanity Fluent Software Language

Pyash: Humanity Fluent Software Language Logan Streondj February 13, 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Problem ................................... 4 1.1.1 Disglossia ............................... 4 1.2 Paradigm ................................... 5 1.2.1 Easy to write bad code ........................ 5 1.2.2 Obsolete Non-Parallel Paradigms .................... 5 1.3 Inspiration ................................. 5 1.4 Answer .................................... 5 1.4.1 Vocabulary ............................... 5 1.4.2 Grammar ................................ 5 1.4.3 Paradigm ................................ 6 I Core Language 7 2 Phonology 8 2.1 Notes .................................... 8 2.2 Contribution ................................. 8 3 Grammar 10 3.1 Composition ................................. 10 3.2 Grammar Tree ................................. 10 3.3 Noun Classes ................................. 10 3.3.1 grammatical number .......................... 12 3.3.2 noun classes for relative adjustment ................. 12 3.3.3 noun classes by animacy ........................ 13 3.3.4 noun classes regarding reproductive attributes ............ 13 3.4 Tense .................................... 13 3.5 Aspects ................................... 13 3.6 Grammatical Mood ............................... 14 3.7 participles ................................. 16 4 Dictionary 18 4.1 Prosody ................................... 18 4.2 Trochaic Rhythm ............................... 18 4.3 Espeak .................................... 18 4.4 -

Cross-Linguistic Variation in Modality Systems: the Role of Mood∗

Semantics & Pragmatics Volume 3, Article 9: 1–74, 2010 doi: 10.3765/sp.3.9 Cross-linguistic variation in modality systems: The role of mood∗ Lisa Matthewson University of British Columbia Received 2009-07-14 = First Decision 2009-08-20 = Revision Received 2010-02-01 = Accepted 2010-03-25 = Final Version Received 2010-05-31 = Published 2010-08-06 Abstract The St’át’imcets (Lillooet Salish) subjunctive mood appears in nine distinct environments, with a range of semantic effects, including weakening an imperative to a polite request, turning a question into an uncertainty statement, and creating an ignorance free relative. The St’át’imcets subjunc- tive also differs from Indo-European subjunctives in that it is not selected by attitude verbs. In this paper I account for the St’át’imcets subjunctive using Portner’s (1997) proposal that moods restrict the conversational background of a governing modal. I argue that the St’át’imcets subjunctive restricts the conversational background of a governing modal, but in a way which obli- gatorily weakens the modal’s force. This obligatory modal weakening — not found with Indo-European non-indicative moods — correlates with the fact that St’át’imcets modals differ from Indo-European modals along the same dimension. While Indo-European modals typically lexically encode quantifi- cational force, but leave conversational background to context, St’át’imcets modals encode conversational background, but leave quantificational force to context (Matthewson, Rullmann & Davis 2007, Rullmann, Matthewson & Davis 2008). Keywords: Subjunctive, mood, irrealis, modals, imperatives, evidentials, questions, free relatives, attitude verbs, Salish ∗ I am very grateful to St’át’imcets consultants Carl Alexander, Gertrude Ned, Laura Thevarge, Rose Agnes Whitley and the late Beverley Frank. -

The Investigation of Mandarin Aspect: with Special Reference to the Ba-Construction

The Investigation of Mandarin Aspect: With Special Reference to the Ba-Construction Ying-Ju Chang PhD University of York Language and Linguistic Science December 2019 Abstract This thesis is an investigation of the aspect system in Taiwanese Mandarin (TM). It examines the four aspect particles le, guo, zai, zhe and two constructions, the reduplicative verb construction and the resultative verb construction. It also explores the aspect of the ba-construction used in TM. Different from previous research, this study adopts the three-dimension model of aspect established by Declerck, Reed, & Cappelle (2006) as the basic framework. To better apply the model to analysing the aspect in TM, I draw from Depraetere's (1995) conceptual definition of (non)boundedness, the semantic feature that the actualisation aspect pivots on, to conduct the analysis at the actualisational level. I also use Klein's (1994) framework, treating the perfect as a category of aspect, rather than of tense. Additionally, Smith's (1997) approach of temporal boundary to define the viewpoint aspect is also used in this study. Chapter 1 lays the conceptual foundation of the thesis, introducing the general background, the sociolinguistic background of Taiwan, the aims and approach of this research and key terminologies. Chapter 2 reviews Smith’s and Klein’s frameworks of aspect as well as the syntactic account of the ba-construction proposed by Sybesma (1999) and C.-T. J. Huang, Li, & Li (2009). In the end, I propose a syntactic structure for the ba-construction. Chapter 3 is the full analysis of the aspect in TM on the basis of the three-dimension model.