Evaluation of the First Five Years of GAVI Immunization Services Support Funding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

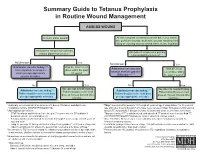

Summary Guide to Tetanus Prophylaxis in Routine Wound Management

Summary Guide to Tetanus Prophylaxis in Routine Wound Management ASSESS WOUND A clean, minor wound All other wounds (contaminated with dirt, feces, saliva, soil; puncture wounds; avulsions; wounds resulting from flying or crushing objects, animal bites, burns, frostbite) Has patient completed a primary Has patient completed a primary tetanus diphtheria series?1, 7 tetanus diphtheria series?1, 7 No/Unknown Yes No/Unknown Yes Administer vaccine today.2,3,4 Was the most recent Administer vaccine and Was the most Instruct patient to complete dose within the past tetanus immune gobulin recent dose within series per age-appropriate 10 years? (TIG) now.2,4,5,6,7 the past 5 years?7 vaccine schedule. No Yes No Yes Vaccine not needed today. Vaccine not needed today. Administer vaccine today.2,4 2,4 Patient should receive next Administer vaccine today. Patient should receive next Patient should receive next dose Patient should receive next dose dose at 10-year interval after dose at 10-year interval after per age-appropriate schedule. per age-appropriate schedule. last dose. last dose. 1 A primary series consists of a minimum of 3 doses of tetanus- and diphtheria- 4 Tdap* is preferred for persons 11 through 64 years of age if using Adacel* or 10 years of containing vaccine (DTaP/DTP/Tdap/DT/Td). age and older if using Boostrix* who have never received Tdap. Td is preferred to tetanus 2 Age-appropriate vaccine: toxoid (TT) for persons 7 through 9 years, 65 years and older, or who have received a • DTaP for infants and children 6 weeks up to 7 years of age (or DT pediatric if Tdap previously. -

Vaccines 101 the Very Last Day That I Was a Pediatric Resident. Um, Many

Vaccines 101 The very last day that I was a pediatric resident. Um, many years ago, a toddler walked into the emergency room and uh, and progressively got sicker and sicker. That's Dr. Katherine Edwards, a world expert in pediatric infectious disease in vaccinology. She's also a professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt university and she's been working on vaccines for 40 years. I did a spinal tap on her and realized that she had Haemophilus influenza, typ e B meningitis, Haemophilus influenza, type B or HIB is it bacteria normally found in our nose and throat that can lead to very serious life threatening infections and no matter what I did in that day and into the night in terms of prompt antibiotics and she'd just been sick a few hours and, and fluids and all the, you know, ventilators and all the best things that modern medicine, she died, the vaccine for hip was not available until the 1990s. And until it did become available, hip disease affected approximately 25,000 children each year with things like meningitis, pneumonia, and bloodstream infections. And at that time in the hospital that I was practicing at any one time, there were generally five or six patients that had Haemophilus meningitis or invasive disease or some complication of this particular infection. And we knew that from the basic science that if you had antibody to the capsule or to the coat of the organism, that you were protected from disease. But we really didn't know how to make little kids make antibody. -

Vaccine Hesitancy

Vaccine Hesitancy Dr Brenda Corcoran National Immunisation Office Presentation Outline An understanding of the following principles: • Overview of immunity • Different types of vaccines and vaccine contents • Vaccine failures • Time intervals between vaccine doses • Vaccine overload • Adverse reactions • Herd immunity Immunity Immunity • The ability of the human body to protect itself from infectious disease The immune system • Cells with a protective function in the – bone marrow – thymus – lymphatic system of ducts and nodes – spleen –blood Types of immunity Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immunological_memory Natural (innate) immunity Non-specific mechanisms – Physical barriers • skin and mucous membranes – Chemical barriers • gastric and digestive enzymes – Cellular and protein secretions • phagocytes, macrophages, complement system ** No “memory” of protection exists afterwards ** Passive immunity – adaptive mechanisms Natural • maternal transfer of antibodies to infant via placenta Artificial • administration of pre- formed substance to provide immediate but short-term protection (antitoxin, antibodies) Protection is temporary and wanes with time (usually few months) Active immunity – adaptive mechanisms Natural • following contact with organism Artificial • administration of agent to stimulate immune response (immunisation) Acquired through contact with an micro-organism Protection produced by individual’s own immune system Protection often life-long but may need boosting How vaccines work • Induce active immunity – Immunity and immunologic memory similar to natural infection but without risk of disease • Immunological memory allows – Rapid recognition and response to pathogen – Prevent or modify effect of disease Live attenuated vaccines Weakened viruses /bacteria – Achieved by growing numerous generations in laboratory – Produces long lasting immune response after one or two doses – Stimulates immune system to react as it does to natural infection – Can cause mild form of the disease (e.g. -

The Challenge of Achieving Universal Access to Vaccines

Keynote Address: The Challenge of Achieving Universal Access to Vaccines WIPO & AMF Seth Berkley M.D, CEO 8 November 2017 www.gavi.org 1 Vaccine landscape WIPO 8 November 2017 The world before vaccines Examples of major disease outbreaks Polio Cholera New York pandemic 1916 Europe 6,000 deaths 1829-1851 >200,000 deaths Yellow fever Philadelphia Smallpox 1793 epidemic >5,000 India deaths 1974 15,000 deaths Flu pandemic 1918-1920 > 50-100 million deaths worldwide WIPO 8 November 2017 History of vaccine development Source: Delaney et.al. 2014 WIPO 8 November 2017 Cumulative number of vaccines developed licensed 50+ vaccines Lyme OspA, protein (1998) Tuberculosis (Bacille Calmette-Guérin) Pneumococcal conjugate, heptavalent* (2000) 1927 Typhus Varicella (1995) Meningococcal quadrivalent conjugates* (2005) Japanese encephalitis (Vera-cell) (2009) 1938 Cholera (recombinant Toxin B) # (1993) Cholera (WC only) (2009) Tetanus toxoid Cholera (WC-rBC) (1991) Human papillomavirus recombinant bivalent (2009) Influenza H. influenzaeconjugate* (1987) Quadrivalent influenza vaccines (2012) Typhoid Cholera Pertussis 1936 Meningococcal C and Y and 1886 1896 1926 H. influenza type B polysaccharide (1985) Haemophilusinfluenza type b (2012) Adenovirus (1980) Meningococcal B (2013) Smallpox Diphtheria Yellow Rabies, cell culture (1980) Influenza vaccine (baculovirus) (2013) 1798 toxoid Fever Typhoid conjugate vaccine (2013) Rabies Plague Meningococcal polysaccharides (1974) 1923 1935 Human papillomavirus, 9-valent (2014) 1885 Rubella, live (1969) 1897 vaccines -

Package Inserts

Individuals using assistive technology may not be able to fully access the information contained in this file. For assistance, please send an e-mail to: [email protected] and include 508 Accommodation and the title of the document in the subject line of your e-mail. HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION -----------------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS------------------------ These highlights do not include all the information needed to use • Carefully consider benefits and risks before administering VAXELIS to VAXELIS safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for persons with a history of: VAXELIS. - fever ≥40.5°C (≥105°F), hypotonic-hyporesponsive episode (HHE) or VAXELISTM (Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids and Acellular Pertussis, persistent, inconsolable crying lasting ≥3 hours within 48 hours after a Inactivated Poliovirus, Haemophilus b Conjugate and Hepatitis B previous pertussis-containing vaccine. (5.2) Vaccine) - seizures within 3 days after a previous pertussis-containing vaccine. (5.2) Suspension for Intramuscular Injection Initial U.S. Approval: 2018 • If Guillain-Barré syndrome occurred within 6 weeks of receipt of a prior vaccine containing tetanus toxoid, the risk for Guillain-Barré syndrome ----------------------------RECENT MAJOR CHANGES ------------------------ may be increased following VAXELIS. (5.3) Dosage and Administration (2.2) 09/2020 • Apnea following intramuscular vaccination has been observed in some ----------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE--------------------------- infants born prematurely. The decision about when to administer an VAXELIS is a vaccine indicated for active immunization to prevent intramuscular vaccine, including VAXELIS, to an infant born prematurely diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, hepatitis B, and invasive disease should be based on consideration of the individual infant’s medical status due to Haemophilus influenzae type b. -

Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS)

Appendix D Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) VAERS is a national post-licensure vaccine safety surveillance program co-managed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). VAERS serves as an early warning system to detect possible safety issues with U.S. vaccines by collecting information about adverse events (possible side effects or health problems) that occur after vaccination. A report to VAERS does not indicate that a vaccine caused an adverse event, only that the adverse event occurred sometime after vaccination. Who can report? Anyone can submit a report to VAERS — healthcare professionals, vaccine manufacturers, and the general public. VAERS welcomes all reports, regardless of seriousness, and regardless of how likely the vaccine may have been to have caused the adverse event. What should be reported? Healthcare providers are required by law to report: y Any adverse event listed by the vaccine manufacturer as a contraindication to subsequent doses of the vaccine y Any adverse event listed in the Reportable Events Table that occurs within the specified time period after the vaccination. Healthcare providers are strongly encouraged to report: y Any adverse event that occurs after the administration of a vaccine licensed in the United States, whether it is or is not clear that a vaccine caused the adverse event y Vaccine administration errors A copy of the Reportable Events Table can be found on the following page, or at https://vaers.hhs.gov/resources/infoproviders.html Note: COVID-19 vaccines under an Emergency Use Authorization have additional VAERS reporting requirements. -

Vaccination and Multiple Sclerosis in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp-2021-326839 on 5 August 2021. Downloaded from Occasional essay Vaccination and multiple sclerosis in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic Tobias Monschein ,1 Hans- Peter Hartung,1,2 Tobias Zrzavy ,1 Michael Barnett ,3 Nina Boxberger,4 Thomas Berger,1 Jeremy Chataway,5 Amit Bar- Or,6 Paulus Stefan Rommer ,1,4 Uwe K. Zettl4 24 ► Additional supplemental INTRODUCTION higher binding affinity. On entering the respira- material is published online In the last century, several pandemics were caused tory epithelial cells, SARS-CoV -2 starts replicating only. To view, please visit by various influenza virus subtypes, with the Spanish and spreading rapidly until it reaches the alveolar the journal online (http:// dx. 1 doi. org/ 10. 1136/ jnnp- 2021- influenza of 1918–1920 being the most severe. epithelial cells of the lung. Hence, a robust innate 326839). Coronaviruses were first described in humans in immune response is triggered.25 The spike protein the 1960s, and since then seven human pathogenic is recognised by pattern recognition receptors For numbered affiliations see coronaviruses have been described.2 The first severe and leads, via downstream signalling, to increased end of article. outbreak was in 2002 with the severe acute respira- interferon production by innate immune cells. Antigen- specific adaptive immunity is critical for Correspondence to tory syndrome coronavirus (SARS- CoV), followed Dr Tobias Monschein, by the Middle East respiratory syndrome corona- the immune response to SARS- CoV-2 infection. Department of Neurology, virus (MERS- CoV) outbreak in 2012.3 The current Both CD8 and CD4 T cells are activated via their Medical University of Vienna, COVID-19 pandemic, which broke out in Wuhan, respective major histocompatibility complexes I or Vienna, Austria; tobias. -

Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid and Acellular

54 Women’s Health FAMILY P RACTICE N EWS • March 15, 2006 C LINICAL C APSULES Digital Mammography Best for Some women for whom the investigators had all A large, head-to-head comparison of dig- relevant information (N. Engl. J. Med. Prolapse Hinders Quality of Life Although body image has been shown ital and film mammography found no 2005;353:[Epub ahead of print] doi10.1056/ Advanced pelvic organ prolapse negative- to be important in quality of life and the overall difference in diagnostic accuracy, nejmoa052911, www.nejm.org). ly affects body image and quality of life, effect of advanced organ prolapse on body but digital mammography seems to have All women underwent digital and film Dr. Erik Jelovsek reported at the annual image might seem obvious, no one has better diagnostic accuracy in some sub- mammography, independently interpret- meeting of the American Urogynecolog- specifically assessed this or the relationship groups. ed by two readers. Readers rated the mam- ic Society. between body image and quality of life in Digital mammography was significant- mograms on a 7-point malignancy scale In a case-control study with 47 case pa- these patients, he noted. ly more accurate among women under age and used the classification of the Breast tients and 51 controls, a validated body im- These findings indicate that there is in- 50, women with heterogeneously dense or Imaging Reporting and Data System. age scale showed that case patients were deed a condition-specific decrease in qual- extremely dense breasts, and pre- Biopsy or aspiration of the suspicious le- less likely to feel physically attractive (ad- ity of life among women with advanced menopausal or perimenopausal women, sion was performed if either reader rec- justed odds ratio 11.3), sexually attractive pelvic organ prolapse and suggest that Dr. -

I M M U N O L O G Y Core Notes

II MM MM UU NN OO LL OO GG YY CCOORREE NNOOTTEESS MEDICAL IMMUNOLOGY 544 FALL 2011 Dr. George A. Gutman SCHOOL OF MEDICINE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE (Copyright) 2011 Regents of the University of California TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2 ANTIGEN/ANTIBODY INTERACTIONS ..............................................9 CHAPTER 3 ANTIBODY STRUCTURE I..................................................................17 CHAPTER 4 ANTIBODY STRUCTURE II.................................................................23 CHAPTER 5 COMPLEMENT...................................................................................... 33 CHAPTER 6 ANTIBODY GENETICS, ISOTYPES, ALLOTYPES, IDIOTYPES.....45 CHAPTER 7 CELLULAR BASIS OF ANTIBODY DIVERSITY: CLONAL SELECTION..................................................................53 CHAPTER 8 GENETIC BASIS OF ANTIBODY DIVERSITY...................................61 CHAPTER 9 IMMUNOGLOBULIN BIOSYNTHESIS ...............................................69 CHAPTER 10 BLOOD GROUPS: ABO AND Rh .........................................................77 CHAPTER 11 CELL-MEDIATED IMMUNITY AND MHC ........................................83 CHAPTER 12 CELL INTERACTIONS IN CELL MEDIATED IMMUNITY ..............91 CHAPTER 13 T-CELL/B-CELL COOPERATION IN HUMORAL IMMUNITY......105 CHAPTER 14 CELL SURFACE MARKERS OF T-CELLS, B-CELLS AND MACROPHAGES...............................................................111 -

Standing Orders for Administering Td/Tdap Vaccine to Adults

Standing orders for other vaccines are available at www.immunize.org/standing-orders. note: This standing orders template may be adapted per a practice’s discretion without obtaining permission from IAC. As a courtesy, please acknowledge IAC as its source. standing orders for Administering Td/Tdap Vaccine to Adults Purpose To reduce morbidity and mortality from tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis infection by vaccinating all adults who meet the criteria established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Policy Where allowed by state law, standing orders enable eligible nurses and other healthcare professionals (e.g., pharma- cists) to assess the need for vaccination and to vaccinate adults who meet any of the criteria below. Procedure 1 Assess Adults for Need of Vaccination against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis based on the following criteria: • Lack of documentation of ever receiving a dose of tetanus and diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) as an adolescent or adult • Currently pregnant (preferably between 27 and 36 weeks gestation) and no documentation of Tdap given during current pregnancy • Lack of documentation of receiving at least 3 doses of tetanus- and diphtheria-containing toxoids • Completion of a 3-dose primary series of tetanus- and diphtheria-containing toxoids with no documentation of receiving a booster dose in the previous 10 years • Recent deep and dirty wound (e.g., contaminated with dirt, feces, saliva) and lack of evidence of having received tetanus toxoid-containing vaccine in the previous 5 years 2 Screen for Contraindications and Precautions Contraindications • Do not give Tdap or Td to a person who has experienced a serious systemic or anaphylactic reaction to a prior dose of either vaccine or to any of its components. -

Substituting Thimerosal Preservative Used in Vaccines: FDA Perspective

Substituting Thimerosal Preservative used in Vaccines: FDA perspective Robert Ball, MD, MPH, ScM FDA/CBER/OBE April 4, 2012 1 Objectives § Requirement for preservative in multi-dose vaccine formulations § Food & Drug Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA 1997) § Data review § US licensed childhood vaccines § Preservative used in US licensed vaccines § Substituting Thimerosal preservative in US licensed vaccines 2 Use of Preservative in Vaccines § Preservatives are compounds that kill or prevent the growth of microorganisms, particularly bacteria and fungi § Used in vaccines to prevent microbial growth in the event that the vaccine is accidentally contaminated, as might occur with repeated puncture of multi-dose vials § In some cases, preservatives are added during manufacture to prevent microbial growth 3 Use of Preservative in Vaccines § United States Code of Federal Regulations (the CFR) requires, in general, the addition of a preservative to multi-dose vials of vaccines; [21 CFR 610.15(a)] § Thimerosal § An organic mercury-containing preservative used in US-licensed vaccines since the 1930s § Primary purpose is to prevent microbial growth during storage and use § Used in manufacturing process for some vaccines (e.g., inactivation of vaccine antigens in whole-cell pertussis vaccine) § Long record of safe and effective use preventing bacterial and fungal contamination of vaccines 4 Examples of US Licensed Pediatric Vaccines Vaccine Tradename Hg Concentration Thimerosal as a preservative DTaP Infanrix Free no Daptacel Free no DTaP-HepB-IPV Pediarix <0.0125 µg Hg/0.5mL no Pneumococcal conjugate Prevnar 13 Free no Inactivated Poliovirus IPOL Free no Varicella (chicken pox) Varivax Free no Rotavirus Rotateq/Rotarix Free no Mumps, measles, rubella M-M-R-II Free no Hepatitis B Recombivax HB Free no Engerix B Free no Haemophilus influenzae type b ActHIB Free no conjugate (Hib) PedvaxHIB Free no Hib/Hepatitis B comb. -

Arthus Reaction As an Adverse Event Following Tdap Vaccination

Review Arthus Reaction as an Adverse Event Following Tdap Vaccination Vitali Pool 1,*, Larissa Mege 2 and Adel Abou-Ali 3 1 Sanofi Pasteur Inc., Discovery Drive, Swiftwater, PA 18370, USA 2 Sanofi Pasteur SA, 14 Espace Henry Vallée, 69007 Lyon, France; Larissa.Mege@sanofi.com 3 Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc., Northbrook, IL 60062, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: vitali.pool@sanofi.com Received: 8 June 2020; Accepted: 9 July 2020; Published: 14 July 2020 Abstract: Repeat administration of tetanus toxoid-containing vaccines has rarely been associated with Arthus phenomenon, an immune-complex reaction. In the US, since 2013, tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccines (Tdap) have been recommended for administration during each pregnancy. Separately, in 2019, one Tdap was approved for repeat administration in adults in the US. We aimed to describe trends in spontaneously reported Arthus reactions following Tdap in the US and to assess the risk of this phenomenon in persons receiving Tdap repeatedly. We reviewed Arthus reports in the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS), 1990–2018. Reporting rates were estimated using Tdap doses distributed data. A systematic literature review was conducted in MEDLINE for any Arthus cases reported in Tdap clinical trials and observational studies published between 2000 and 2019. We found 192 Arthus reports in VAERS after any vaccine, of which 36 occurred after Tdap and none were reported during pregnancy. The Arthus reporting rate was estimated at 0.1 per million doses distributed. We identified eight published studies of Tdap administration within five years after a previous dose of tetanus toxoid-containing vaccine; no Arthus cases were reported.