Informality, Redevelopment, and the Politics of Limpieza in the Dominican Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

Press release 27 October 2011 Contract worth €325 million Alstom to supply line 2 of Los Teques metro in Venezuela « Consorcio Linea 2 »1 has awarded a contract globally worth €530 million to the Alstom-led consortium “Grupo de Empresas” to build the second line of Los Teques metro in Miranda State, Venezuela. The line, 12 km long and served by 6 stations, will enter service in October 2015. Alstom’s share of the contract is worth around €325 million. Alstom – which has a share of the consortium of over 60%, along with Colas Rail (22%) and Thales (17%) - will undertake the global coordination of the project, including engineering, integration and commissioning of the electromechanical works on a turnkey basis. In addition, the company will supply 22 metro trains of 6 cars each, medium voltage electrification, traction substations and part of the signalling equipment. The metro trains are from the Alstom’s standard Metropolis platform. Los Teques metro is a suburban mass-transit extension of the Caracas metro system (opening of the first line in 1983, 4 lines currently in commercial service, 600 cars supplied by Alstom). It has been designed to connect the Venezuelan capital to the city of Los Teques. The contract for the supply of the electromechanical system for the line 1 (9.5 km, 2 stations) was signed in October 2005 during a bilateral meeting between France and Venezuela in Paris. This line was inaugurated before the last Presidential elections in November 2006. Line 1 of Los Teques metro currently carries over 42,000 passengers per day. -

How People Face Evictions

Edited by Yves Cabannes, Silvia Guimarães Yafai and Cassidy Johnson HOW PEOPLE FACE EVICTIONS ● Mirshāq and sarandū ● durban ● Karachi ● istanbul ● hangzhou ● santo doMingo ● Porto alegre ● buenos aires ● development planning b s h f unit Institutional partnership DEVELOPMENT PLANNING UNIT, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON (DPU/UCL) 34 Tavistock Square, London, WC1H 9EZ, United Kingdom www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu BUILDING AND SOCIAL HOUSING FOUNDATION (BSHF) Memorial Square, Coalville, Leicestershire, LE67 3TU, United Kingdom www.bshf.org Research coordination and editing team Research Coordinator: Prof. Yves Cabannes, Chair of Development Planning, DPU/UCL [email protected] Silvia Guimarães Yafai, Head of International Programmes, BSHF [email protected] Cassidy Johnson, Lecturer, MSc Building and Urban Design in Development, DPU/UCL [email protected] Local research teams The names of the individual authors and members of the local research teams are indicated on the front of each of the cases included in the report. Translation English to Spanish: Isabel Aguirre Millet Spanish and Portuguese to English: Richard Huber Arabic to English: Rabie Wahba and Mandy Fahmi Graphics and layout Janset Shawash, PhD candidate, Development Planning Unit, DPU/UCL [email protected] Extracts from the text of this publication may be reproduced without further permission provided that the source is fully acknowledged. Published May 2010 © Development Planning Unit/ University College London 2010 ISBN: 978-1-901742-14-5 Cover image © Abahlali baseMjondolo CONTENTS 1 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 7 Putting the cases in perspective Yves Cabannes Cases from Africa and the Middle East 18 Mirshāq, Dakhaliyah governorate and Sarandū, Buheira governorate, Egypt 21 1. -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

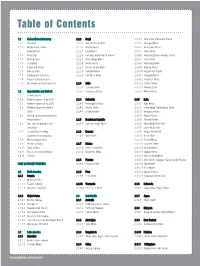

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

An Overviewoverview Madrid Region 6,000,000 Citizens Spain

MetroMetroMetro dedede MadridMadridMadrid AnAn overviewoverview Madrid Region 6,000,000 Citizens Spain Madrid TOTAL AREA 8.000 km 2 300,000 Citizens San Sebasti án de los Reyes Alcobendas Las Rozas Torrej ón de Ardoz Majadahonda Henares River Corridor 500,000 Citizens San Fernando MadridMadrid Coslada 3,000,000 Citizens Alcorc ón Legan és Móstoles km Southwest km 30 30 1,000,000 Citizens 30 Getafe Fuenlabrada 40 km CONTEXT During the last years, Madrid has become to be one of the main capitals in the world The infrastructure and public works policy of the Regional (Comunidad de Madrid) and Local (Ayuntamiento) Goverments has contributed to this development One of the biggest success of this policy is the increment of the movility , making the Madrid region an attractive place for the investors The Network of Metro de Madrid is now a world class rail transport system reference for financial multilateral institutions and local administrations that face metropolitan and railway projects The quality of the management model of Metro de Madrid set a reference in the railway undertakers and public operators. Metro de Madrid has taken the decision to export his know-how, experience and management model in order to share our success and help cities all around the world to get the shortest way to reach the best mass transit system according they own needs. COMUNIDAD DE MADRID (REGIONAL GOVERNMENT) M I N I S T R I E S ·········· ·········· Consejería de Transportes ·········· ·········· ·········· ······ ······ e Infraestructuras ······ ······ -

Santo Domingo Metro Financing Rolling Stock and Mechanical Equipment

Institutional Clients Group Santo Domingo Metro Financing rolling stock and mechanical equipment Case Study The Challenge The Santo Domingo Metro is a rapid transit system in Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. In January 2009, Line One of the Metro began providing commercial services. The Metro System is the first in the country and second in the Caribbean. Daily ridership on Line One is approximately 105,000 people. Construction of Line Two of the Metro is underway. In order to purchase electromechanical equipment and rolling stock components, €270 million of financing was required. The electromechanical equipment will be supplied by the Eurodom Consortium made up of Thales and TIM/TSO, and the rolling stock by Alstom Transport, with the equipment originating in Spain, France, Germany and Belgium. With this project total ridership per day will increase to 250,000 people. The Ministry of Finance of the Dominican Republic is guarantor of the facilities, providing an unconditional, irrevocable guarantee supporting the borrower under the facilities. The Office for the Restructuring of Transit (OPRET) is the borrower. The Solution Citi participated as a mandated co-lead arranger in a syndicated €270 million Export Credit Agency-supported (ECA) financing for OPRET to finance the purchase of the electromechanical equipment and rolling stock components for Line Two of the Santo Domingo Metro. Citi, and the other mandated lead arrangers, leveraged the financial structure that had been implemented for the Line One financing of the Metro. This allowed for certain and rapid execution of the Line Two transaction. The Result The inclusion of four ECAs enabled OPRET to maximize ECA-supported financing and minimize commercial debt in its financing mix. -

Dominican Republic

RENEWABLE ENERGY PROSPECTS: DOMINICAN RENEWABLE ENERGY PROSPECTS: DOMINICAN PROSPECTS: ENERGY RENEWABLE REPUBLIC REPUBLIC November 2016 A ©IRENA UnlessotherwisestatedthispublicationandmaterialfeaturedhereinarethepropertyoftheInternationalRenewableEnergyAgency(IRENA) andaresubjecttocopyrightbyIRENAMaterialinthispublicationmaybefreelyusedsharedcopiedreproducedprintedandorstored providedthatallsuchmaterialisclearlyattributedtoIRENAMaterialcontainedinthispublicationattributedtothirdpartiesmaybesubjectto third-partycopyrightandseparatetermsofuseandrestrictionsincludingrestrictionsinrelationtoanycommercialuse ISBN----(print) ISBN----(PDF) AboutIRENA TheInternationalRenewableEnergyAgency(IRENA)isanintergovernmentalorganisationthatsupportscountries intheirtransitiontoasustainableenergyfutureandservesastheprincipalplatformforinternationalco-operationa centreofexcellenceandarepositoryofpolicytechnologyresourceandfi nancialknowledgeonrenewableenergy IRENApromotesthewidespreadadoptionandsustainableuseofallformsofrenewableenergyincludingbioenergy geothermalhydropoweroceansolarandwindenergyinthepursuitofsustainabledevelopmentenergyaccess energysecurityandlow-carboneconomicgrowthandprosperity AboutCNE TheNationalEnergyCommission(CNE)istheinstitutionresponsibleoftheformulationoftheNationalEnergyPlan withaholisticapproachthatcoversallenergysourcestopromoteanenvironmentallysustainableandeconomically sounddevelopmentandcontributestonationalenergypolicydevelopmentCNEpromotesinvestmentsaccording to the strategies defi ned by the energy plan and the Law -to -

How People Face Evictions

HOW PEOPLE FACE EVICTIONS edited by Yves Cabannes Silvia Guimarães Yafai Cassidy Johnson ● MIRSHĀQ AND SARANDŪ ● DURBAN ● KARACHI ● ISTANBUL ● ● HANGZHOU ● SANTO DOMINGO ● PORTO ALEGRE ● BUENOS AIRES ● development planning b s h f unit !"#$%&"'(&$)*+&$,-.+/"01 edited by 2-&1$3*4*00&1$ 5.(-.*$67.8*9:&1$2*;*. 3*11.<=$>"?01"0 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING UNIT @ABCDBE6$FED$5G3BFC$!GA5BE6$)GAEDFHBGE$ !"#$%&$'"()*+(,%"-,#./+* D,I,CG%J,EH$%CFEEBE6$AEBHK$AEBI,L5BH2$3GCC,6,$CGEDGE$MD%ANA3CO PQ$H*-.1R"+S$5T7*9&K$C"0<"0K$U3V!$W,XK$A0.R&<$Y.0Z<"8 www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu @ABCDBE6$FED$5G3BFC$!GA5BE6$)GAEDFHBGE$M@5!)O J&8"9.*($5T7*9&K$3"*(-.((&K$C&.+&1R&91?.9&K$C,[\$PHAK$A0.R&<$Y.0Z<"8 www.bshf.org 0-#-(,1.*1'',2/"($'"*("2*-2/$"3*%-(4* L&1&*9+?$3""9<.0*R"9]$%9";^$2-&1$3*4*00&1K$3?*.9$";$D&-&("'8&0R$%(*00.0ZK$D%ANA3C [email protected] 5.(-.*$67.8*9:&1$2*;*.K$!&*<$";$B0R&90*/"0*($%9"Z9*88&1K$@5!)$ [email protected] 3*11.<=$>"?01"0K$C&+R79&9K$J5+$@7.(<.0Z$*0<$A94*0$D&1.Z0$.0$D&-&("'8&0RK$D%ANA3C [email protected] 5'1()*,-#-(,1.*%-(4#* H?&$0*8&1$";$R?&$.0<.-.<7*($*7R?"91$*0<$8&84&91$";$R?&$("+*($9&1&*9+?$R&*81$*9&$.0<.+*R&<$"0$R?&$;9"0R$ ";$&*+?$";$R?&$+*1&1$.0+(7<&<$.0$R?&$9&'"9R^ 6,("#)($'" ,0Z(.1?$R"$5'*0.1?]$B1*4&($FZ7.99&$J.((&R$ 5'*0.1?$*0<$%"9R7Z7&1&$R"$,0Z(.1?]$L.+?*9<$!74&9 F9*4.+$R"$,0Z(.1?]$L*4.&$U*?4*$*0<$J*0<=$)*?8. -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

GLOBALGLOBAL METROMETRO RAILRAIL PROJECTSPROJECTS REPORT:REPORT: MARKETMARKET ANDAND INVESTMENTINVESTMENT OUTLOOKOUTLOOK 2020-20302020-2030 Global Mass Transit Research has just launched the fifth edition of the Global Metro Rail Projects Report: Market and Investment Outlook 2020-22030, the most comprehensive and up- to-date study on the metro rail segment. The report will provide information on the top 150 metro rail projects in the world in terms of upcoming investments and plans. It will provide details on the existing network, stations, ridership, rolling stock, technology and fare systems. It will highlight upcoming capital investment needs and opportunities such as construc- tion of new lines and extensions, upgrades of existing lines, procurement and refurbishment of rolling stock, upgrades of power and communication systems, upgrades of fare collec- tion systems, as well as construction and refurbishment of stations. The report will comprise two distinct sections. Part 1 of the report (PPT format converted to PDF) will describe the existing state of, and - Current ridership the expected opportunities in, the global metro rail industry in terms of network and sta- - Current rolling stock (number of rail cars, technology, suppliers, age, etc.) tion construction and development, ridership, rolling stock, signalling, fare system, power, - Existing signalling system (type of system, suppliers, etc.) tracks, consulting, etc. It will examine the recent technical and financing developments; - Power and tracks analyse key growth drivers and challenges; and assess the upcoming opportunities and - Current fare system (type of system, ticketing infrastructure, suppliers, etc.) future outlook for the industry. - Extensions/ Capital projects - upcoming network and stations - Planned investments, cost estimates and funding Part 2 of the report (MS Word converted to PDF) will provide updated information on 150 - Projected ridership projects that present significant capital investment opportunities. -

Dominican Republic Briefing Packet

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se DOMINICAN REPUBLIC P RE- F I ELD B RIEFING P ACKET 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 PUBLIC HEALTH OVERVIEW 4 STATISTICS 9 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 12 HISTORY OVERVIEW Error! Bookmark not defined. Geography 14 Climate and Weather 16 Demographics 16 Economy 17 Education 18 Religion 18 Modern life Error! Bookmark not defined. Poverty 19 NATIONAL FLAG 19 Etiquette Error! Bookmark not defined. CULTURE 22 Orientation Error! Bookmark not defined. Food and Economy 23 Social Stratification 23 Gender Roles and Statuses 23 Marriage, Family, and Kinship 23 Socialization 24 Etiquette Error! Bookmark not defined. Religion Error! Bookmark not defined. Medicine and Health Care Error! Bookmark not defined. Secular Celebrations 25 USEFUL Spanish PHRASES 25 SAFETY 28 GOVERNMENT 30 Currency 30 CURRENT CONVERSATION RATE OF 2018 31 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 31 TIME IN DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 32 EMBASSY INFORMATION 32 Embassy of the United States of America 32 Embassy of Dominican Republic in the United States 32 WEBSITES 33 2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the Dominican Republic Medical and Dental Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The first section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. -

Chapter 2: Aid-For-Trade Flows and Financing

CHAPTER 2: AID-FOR-TRADE FLOWS AND FINANCING CHAPTER 2: AID-FOR-TRADE FLOWS AND FINANCING his chapter provides a comprehensive overview of aid-for-trade flows, ODA Tcommitments and disbursements, trade-related Other Official Flows (OOF) and South-South trade-related co-operation. It examines aid-for-trade flows using data from the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS), complemented by findings from the OECD/ WTO monitoring survey. It examines recipients and providers of assistance, the financial terms of assistance, and the outlook for aid for trade. In the context of the economic crisis in many OECD member countries, aid for trade (scaled up since 2005) has for the most part been maintained. Aid-for-trade flows declined in 2011, with decreasing support for infrastructure, particularly in Africa. Least developed countries (LDCs) experienced a fall in funding, but they did not bear the brunt of the decline. The flows indicate a shift in funding towards private sector development and value chain promotion. Consequently, flows to meet trade objectives in sectors such as agriculture, industry, and business services are continuing to increase. INTRODUCTION In 2011, overall ODA (excluding debt relief) fell for the first time since 1997, followed by a further fall in 2012. After several years of increasing aid-for-trade flows, the financial crisis and subsequent economic challenges faced by OECD member countries have put pressure on aid budgets. Aid-for-trade commitments declined in 2011, with DAC donors1, in particular the G72 countries, providing less support, especially to infrastructure in Africa. Multilateral institutions maintained support at its 2010 level. -

Santo Domingo Shopping Guide / Santo Domingo 7 Miembros AHSD Members AHSD

La Ruta de las Compras Shopping Route Gastronomía Gastronomy Grandes Marcas Brand Names Shopping Guide / Santo Domingo 1 CONTENIDO | CONTENT 19 6 17 De todo para la familia 15 6. LA RUTA DE COMPRAS Shopping for the family 15 Mapa con las Plazas Comerciales de la ciudad De todo para el hogar 16 6. SHOPPING ROUTE 14 Home shopping 16 Map pointing the Malls you can find in the city Grandes marcas 17 Brand names 17 8. INFORMACIÓN GENERAL Gastronomía variada 19 SOBRE REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA Varied gastronomy 19 8. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Diversión noctura 22 Night life 22 10. CAPITAL DE LAS COMPRAS 23. NÚMEROS IMPORTANTES 10. CAPITAL FOR SHOPPING 23. IMPORTANT NUMBERS Joyería Artesanal 11 Aeropuertos Airports Hand-made Jewelrey 11 Embajadas Embassies Teléfonos Emergencia Emergency numbers Alfarería y Cestería 12 Pottery and Basketry 12 Calle Presidente González esq. Cigarros y Ron 13 Tiradentes. Edif. La Cumbre piso 8 10 Ens. Naco, Santo Domingo, Cigars and Rum 13 República Dominicana. Tel: 809-227-0306. Email: [email protected] Una publicación de / Published by: TARGET CONSULTORES DE MERCADEO www.cometosantodomingo.com Av. 27 de Febrero, Torre KM, Suite 401, Evaristo Morales. Santo Domingo, República Dominicana Tel: 809-532-2006 / E-mail: [email protected] www.targetconsultores.com © Copyright 2015 / Asociación de Hoteles de Santo Domingo All rights reserved. The partial or total reproduction of this guide, as well Textos / Text: Karina López, Yulissa Matos Coordinación / Coordinator: Yajaira Abreu as its broadcast of any kind or by any mean, including photocopying, Traducción/Translation: Elaina Licairac Fotografías / Photos: Realizadas en las instalaciones de Ágora Mall recording or electronic storage and recovery systems, without the written Gastronomía / Gastronomy: Restaurante Jalao Diseño / Layout: Q’ Estudio Creativo Impresión / Printing: Editora Corripio consent of the editors, is prohibited. -

Dominican Republic 12 78 (UNA-DR)

GLOBAL FOUNDATION FOR DEMOCRACY AND DEVELOPEMENT www.globalfoundationdd.org Annual Report 2009 - 2010 dominicanaonline.org Washington, D.C. 1889 F Street, NW 7th Floor Washingto, D.C. 20006 T. +1.202.458.3246 F. +1.202.458.6901 New York 780 Third Avenue 19th Floor New York, N.Y. 10017 T. +1.212.751.5000 F. +1.212.751.7000 www.globalfoundationdd.org GLOBAL FOUNDATION FOR DEMOCRACY AND DEVELOPMENT Editor-in-Chief Natasha Despotovic Texts Photos Margaret Hayward Anne Casale Supervisory Editor Kerry Stefancyk Apolinar Moreno Semiramis de Miranda Asuncion Sanz Alexandra Tabar Yamile Eusebio Coordinating Editors Alicia Alonzo Design Printing Margaret Hayward Emy Rodriguez Miguel F. Sierra Vargas World Press Kerry Stefancyk Mandy Sciacchitano Maria Montas Tel. 703-888-2493 2 GFDD / www.globalfoundationdd.org / Annual Report 2009-2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Prologue by Education and Dr. Leonel Fernández Technology 04 Honorary President 58 Prologue by Collaboration with Natasha Despotovic the Organization of 06 Executive Director 60 American States History and Background Collaboration with 10 of GFDD and FUNGLODE 68 the United Nations United Nations Association Felows Program of the Dominican Republic 12 78 (UNA-DR) Dominican Republic Global International Forums 16 Film Festival (DRGFF) 86 Global Media GFDD/FUNGLODE Arts Institute Awards 26 (GMAI) 88 Environmental Publications and Sustainable (Internet, Print & 36 Development Program 90 Multimedia) InteRDom: Fundraising Internships in the Initiatives 44 Dominican Republic 96 Virtual Educa & Offices and 54 Virtual Educa Caribe 98 Contacts ...these projects have given the country international visibility, have educated national and international audiences, and have created a sense of pride among Dominicans at home and abroad.