UNDERSTANDING PAKISTAN Volume I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronologica Dictionary of Sind Chronologial Dictionary of Sind

CHRONOLOGICA DICTIONARY OF SIND CHRONOLOGIAL DICTIONARY OF SIND (From Geological Times to 1539 A.D.) By M. H. Panhwar Institute of Sindhology University of Sind, Jamshoro Sind-Pakistan All rights reserved. Copyright (c) M. H. Panhwar 1983. Institute of Sindhology Publication No. 99 > First printed — 1983 No. of Copies 2000 40 0-0 Price ^Pt&AW&Q Published By Institute of Sindhlogy, University of Sind Jamshoro, in collabortion with Academy of letters Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Education Islamabad. Printed at Educational Press Dr. Ziauddin Ahmad Road, Karachi. • PUBLISHER'S NOTE Institute of Sindhology is engaged in publishing informative material on - Sind under its scheme of "Documentation, Information and Source material on Sind". The present work is part of this scheme, and is being presented for benefit of all those interested in Sindhological Studies. The Institute has already pulished the following informative material on Sind, which has received due recognition in literary circles. 1. Catalogue of religious literature. 2. Catalogue of Sindhi Magazines and Journals. 3. Directory of Sindhi writers 1943-1973. 4. Source material on Sind. 5. Linguist geography of Sind. 6. Historical geography of Sind. The "Chronological Dictionary of Sind" containing 531 pages, 46 maps 14 charts and 130 figures is one of such publications. The text is arranged year by year, giving incidents, sources and analytical discussions. An elaborate bibliography and index: increases the usefulness of the book. The maps and photographs give pictographic history of Sind and have their own place. Sindhology has also published a number of articles of Mr. M.H. Panhwar, referred in the introduction in the journal Sindhology, to make available to the reader all new information collected, while the book was in press. -

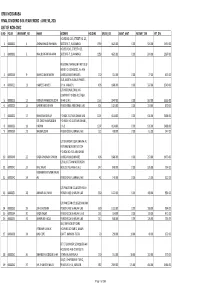

List of Non-CNIC Certificate Holders Final Dividend 2016 31102016.Xlsx

ORIX MODARABA FINAL DIVIDEND 34% YEAR ENDED : JUNE 30, 2016 LIST OF NON-CNIC S.NO FOLIO WARRANT_NO NAME ADDRESS HOLDING GROSS_DIV ZAKAT_AMT INCOME_TAX NET_DIV HOUSE NO. 243, STREET NO. 23, 1 0000002 1 AYSHA KHALID RAHMAN SECTOR E-7, ISLAMABAD. 1359 4621.00 0.00 924.00 3697.00 HOUSE # 243, STREET # 23, 2 0000003 2 KHALID IRFAN RAHMAN SECTOR E-7, ISLAMABAD. 1359 4621.00 0.00 924.00 3697.00 REGIONAL MANAGER FIRST GULF BANK P.O. BOX 18781, AL-AIN 3 0000016 9 SHAHID AMIN SHEIKH UNITED ARAB EMIRATES. 150 510.00 0.00 77.00 433.00 15-B, NORTH AVENUE PHASE I, 4 0000021 11 HAMEED AHMED D.H.A. KARACHI. 496 1686.00 0.00 337.00 1349.00 C/O NATIONAL DRILLING COMPANY P O BOX 4017 ABU 5 0000023 12 MOHSIN HAMEEDDUDDIN DHABI U.A.E. 1161 3947.00 0.00 592.00 3355.00 6 0000025 13 BABER SAEED KHAN PO BOX 3865 ABU DHABI UAE 301 1023.00 0.00 153.00 870.00 7 0000032 17 SHAKEELA BEGUM P.O BOX 2157 ABU DHABI UAE 1207 4104.00 0.00 616.00 3488.00 DR. SYED SHAMSUDDIN P.O. BOX. NO.2157 ABU DHABI., 8 0000033 18 HASHMI U.A.E. 1207 4104.00 0.00 616.00 3488.00 9 0000039 21 NAEEMUDDIN PO BOX 293 FUJAIRAH U.A.E. 120 408.00 0.00 61.00 347.00 C/O SIKANDER IQBAL SHAIKH AL FUTTAIM MOTORS TOYOTA P.O.BOX NO. 555 ABU DHABI 10 0000040 22 RAZIA SHABNAM SHAIKH UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 496 1686.00 0.00 253.00 1433.00 C/O AL FUTTAIM MOTORS PO 11 0000041 23 RIAZ JAVAID BOX 293 FUJAIRAH U.A.E. -

Balkanisation and Political Economy of Pakistan by Yousuf Nazar

BALKANISATION AND POLITICAL ECONOMY OF PAKISTAN YOUSUF NAZAR FOREWORD DR MUBASHIR HASAN @ Copyrights reserved with the author First published in 2008 Revised edition 2011 Published by National News Agency 164 A.M Asad Chamber, Ground Floor, Near Passport Office, Saddar, Karachi, Pakistan. Tel: 021-3568828, 35681520 Fax: 021-35682391 web: www.nnagency.com Email: [email protected] Official Correspondence 4-C, 14th Commercial Street, D.H.A., Phase II Ext., Karachi, Pakistan. Tel: 021-35805391-3 Email: [email protected] Produced and design by Mirador Printed by Elliya Printers This book is dedicated to those 60%-70% Pakistanis who live in poverty and survive on less than 2 Dollars a day About the author Yousuf Nazar is an international finance professional with specialisation in emerging economies. As the head of Citigroup’s emerging markets public equity investments unit based in London from 2001 to 2005, he helped Citigroup manage its over US $2 billion proprietary equity portfolio in the emerging markets of Asia, Latin America, Central/Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa. Before this assignment, he also served as a Director of Citibank’s strategic planning group during the 1990s. Since 2006, he has written many articles on Pakistan’s political and economic issues with a particular focus on the developments in an international context. His interest in politics dates back to his student days as a political activist when he worked against General Zia-ul Haq’s martial law in 1977. His experience in the developing countries spanned across several areas of international finance. He did his Bachelor's degree in administrative studies and an MBA in international finance and economics from York University in Toronto. -

Kurrachee (Karachi) Past: Present and Future

KURRACHEE (KARACHI) PAST: PRESENT AND FUTURE ALEXANDER F. BAILLIE, F.R.G.S., 1880 BIRD'S EYE VIEW OF VICTORIA ROAD CLERK STREET, SADDAR BAZAR KARACHI REPRODUCED BY SANI H. PANHWAR (2019) KUR R A CH EE: PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. KUR R A CH EE: (KA R A CH I) PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. BY A LEXA NDER F.B A ILLIE,F.R.G.S., A uthor of"A PA RA GUA YA N TREA SURE,"etc. W ith M a ps,Pla ns & Photogra phs 1890. Reproduced by Sa niH .Panhw a r (2019) TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE GRANT-DUFF, P.C., G.C.S.I., C.I.E., F.R.S., M.R.A.S., PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, FORMERLY UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA, AND GOVERNOR OF THE PROVINCE OF MADRAS, ETC., ETC., THIS ACCOUNT OF KURRACHEE: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE, IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. INTRODUCTION. THE main objects that I have had in view in publishing a Treatise on Kurrachee are, in the first place, to submit to the Public a succinct collection of facts relating to that City and Port which, at a future period, it might be difficult to retrieve from the records of the Past ; and secondly, to advocate the construction of a Railway system connecting the GateofCentralAsiaand the Valley of the Indus, with the Native Capital of India. I have elsewhere mentioned the authorities to whom I am indebted, and have gratefully acknowledged the valuable assistance that, from numerous sources, has been afforded to me in the compilation of this Work; but an apology is due to my Readers for the comments and discursions that have been interpolated, and which I find, on revisal, occupy a considerable number of the following pages. -

Senator Muhammad Saleh Shah) Chairman

SENATE OF PAKISTAN REPORT OF THE SENATE STANDING COMMITTEE ON STATES AND FRONTIER REGIONS (7th June 2012 TO 26th Nov, 2014) Presented by (SENATOR MUHAMMAD SALEH SHAH) CHAIRMAN Prepared by (MALIK ARSHAD IQBAL) DS/SECRETARY COMMITTEE ii SENATOR MUHAMMAD SALEH SHAH THE HONOURABLE CHAIRMAN, SENATE STANDING COMMITTEE ON STATES AND FRONTIER REGIONS iii iv Description Pages Preface……………………………………………………………………. 1 Executive Summary……………………………………………………..... 3 Senate Standing Committee on States and Frontier Regions (Composition)…......................................................................................... 6 Profiles……………………………………………………………...…….. 7 Meetings of the SSC on States and Frontier Regions (Pictorial view) …… 27 Minutes of the Meeting held on 7th June, 2012 at Islamabad…………..... 33 Minutes of the Meeting held on 26th Sep, 2012 at Islamabad…………..... 35 Minutes of the Meeting held on 20th Nov, 2012 at Islamabad…………… 46 Minutes of the Meeting held on 20th Dec, 2012 at Islamabad………....... 51 Minutes of the Meeting held on 12th Feb, 2013 at Islamabad…………… 64 Minutes of the Meeting held on 19th Feb, 2013 at Islamabad………….... 69 Minutes of the Meeting held on 3rd July, 2013 at Islamabad………….... 76 Minutes of the Meeting held on 9th July, 2013 at Islamabad……..……. 82 Minutes of the Meeting held on 10th Oct, 2013 at Islamabad…………… 87 Minutes of the Meeting held on 19th & 20th Nov, 2013 at Karachi ……. 93 Minutes of the Meeting held on 20th May, 2014 at Islamabad………….. 99 Minutes of the Meeting held on 30th Oct, 2014 at Islamabad……........... 103 Minutes of the Meeting held on 26th Nov, 2014 at Islamabad………….. 107 v PREFACE As the Chairman of the Standing Committee on States and Frontier Regions, I am pleased to present the report of the meetings of the Committee held during the period from 7th June 2012 to 26th Nov, 2014. -

Title Page-Option-0.FH10

ISSN 1728-7715 JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING ARCHITECTURE RESEARCH IN OF JOURNAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING Vol. 15, 2013 (Second Issue) Vol. VOLUME FIFTEEN 2013 (Second Issue) ISSN 1728-7715 JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING VOLUME FIFTEEN 2013 (Second Issue) JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING Editorial Board S.F.A. Rafeeqi Noman Ahmed Anila Naeem Asiya Sadiq Polack Fariha Amjad Ubaid M. Fazal Noor Shabnam Nigar Mumtaz Editorial Associates Farida Abdul Ghaffar Fariha Tahseen Suneela Ahmed Layout and Composition Mirza Kamran Baig Panel of Referees Muzzaffar Mahmood (Ph.D., Professor, PAF KIET, Karachi) Arif Hasan (Architect and Planner, Hilal-e-Imtiaz) Bruno De Meulder (Ph.D., Professor, K.U. Leuven, Belgium) Kamil Khan Mumtaz (ARIBA, Tamgha-e-Imtiaz) Michiel Dehaene (Ph.D., Professor, TUe Eindhoven, Netherlands) Mohammed Mahbubur Rahman (Ph.D., Professor, Kingdom University, Bahrain) Mukhtar Husain (B.Arch., M.Arch., Turkey) Shahid Anwar Khan (Ph.D., AIT, Bangkok Professor, Curtin University, Australia) Naveed Mazhar (Lecturer, NAIT, Alberta, Canada) Pervaiz Vandal (Senior Practicing Architect and Academic) Department of Architecture and Planning, Published by NED University of Engineering and Technology, Karachi, Pakistan. Printed by Khwaja Printers, Karachi. © Copyrights with the Editorial Board of the Journal of Research in Architecture and Planning CONTENTS Editors Note vii Nausheen H. Anwar Thinking Beyond Engines of Growth: Re-Conceptualization Urban Planning -

1 (39Th Session) NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT

1 (39th Session) NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT ———— “QUESTIONS FOR ORAL ANSWERS AND THEIR REPLIES” to be asked at a sitting of the National Assembly to be held on Friday, the 27th January, 2017 50. *Ms. Khalida Mansoor: (Deferred during 36th Session) Will the Minister for Foreign Affairs be pleased to refer to the Starred Question No.189 replied on 05-09-2016 and to state whether barbed wires have been installed and gate has been constructed on Pak-Iran borders? Transferred to Interior Division for answer on Next Rota Day. 52. *Ms. Aisha Syed: (Deferred during 36th Session) Will the Minister for Foreign Affairs be pleased to state whether there is any proposal under consideration of the Government to seal 2600 kilometers Pak-Afghan Road; if so, the date of implementation thereof? Transferred to Interior Division for answer on Next Rota Day. 1. *Mrs. Shahida Rehmani: (Deferred during 38th Session) Will the Minister for Commerce be pleased to state: (a) the details of items exported to India during the last five years; and 2 (b) the details of items imported from India during the year 2011- 12, 2012-13 and 2013-14? Minister for Commerce (Engr. Khurram Dastgir Khan): (a) Pakistan’s exports to India during the last five years are as follows:— Million US$ —————————————————————————————— Years Exports —————————————————————————————— 2011-12 338.517 2012-13 332.690 2013-14 406.963 2014-15 358.082 2015-16 303.581 —————————————————————————————— Source: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics The details of item-wise exports to India during last five years are placed as Annex-I. (b) The total volume of imports from India during the years 2011-12, 2012-13 and 2013-14 are as follows:- Million US$ —————————————————————————————— Years Imports —————————————————————————————— 2011-12 1507.328 2012-13 1809.867 2013-14 2040.376 —————————————————————————————— Source: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics The details of item-wise imports from India during the years 2011-12, 2012-13 and 2013-14 are placed as Annex-II. -

Educationinpakistan a Survey

Education in Pakistan: A Survey ∗ Dr. Tariq Rehman Every year the government of Pakistan publishes some report or the other about education. If not specifically about education, at least the Economic Survey of Pakistan carries a chapter on education. These reports confess that the literacy rate is low, the rate of participation in education at all levels is low and the country is spending too little in this area. Then there one brave promises about the future such as the achievement of hundred percent literacy and increasing the spending on education which has been hovering around 2 percent of the GNP since 1995 to at least 4 percent and so on. Not much is done, though increases in the number of schools, universities and religious seminaries (madaris) is recorded. The private sector mints millions of rupees and thousands of graduates throng the market not getting the jobs they aspired to. The field of education is a graveyard of these aspirations. 1 ∗ Professor of Linguistics, National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. 1. The following indicators point grimly to where Pakistan stands in South Asia. Children not reaching Bangladesh India Nepal Pakistan Sri grade-5 Lanka (1995-1999) Percentages 30 48 56 50 3 Combined enrolment as a Percentage of total 36 54 61 43 66 (These figures are from a UNDP 1991-2000 report quoted in Human Development in South Asia: Globalization and Human Development 2001 (Karachi: Oxford University Press for Mahbub ul Haq Development Centre, 2002). 20 Pakistan Journal of History & Culture, Vol.XX/III/2, 2002 The Historical Legacy South Asia is an heir to a very ancient tradition of both formal and informal learning. -

Shahid Yaqub Abbasi Education 2019 Iub Prr.Pdf

IMPACT OF LEARNING ENVIRONMENT OF CADET COLLEGES ON PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AND LIFE SUCCESS OF STUDENTS IN PAKISTAN SHAHID YAQUB ABBASI Reg. No. 50/IU.PhD/2015 DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION The Islamia University of Bahawalpur PAKISTAN 2019 IMPACT OF LEARNING ENVIRONMENT OF CADET COLLEGES ON PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AND LIFE SUCCESS OF STUDENTS IN PAKISTAN By SHAHID YAQUB ABBASI Reg. No. 50/IU.PhD/2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION The Islamia University of Bahawalpur PAKISTAN 2019 DECLARATION I, Shahid Yaqub Abbasi, Registration No. 50/IU.PhD/2015, Ph.D. Scholar (Session 2015-2018) in the Department of Education, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur hereby declare that the thesis titled, ―Impact of Learning Environment of Cadet Colleges on Personality Development and Life Success of Students in Pakistan‖ submitted by me in partial fulfillment of the requirement of Ph.D. in the subject of Education is my original work. I affirm that it has not been submitted or published earlier. It shall also not be submitted to obtain any degree to any other university or institution. Shahid Yaqub Abbasi i FORWARDING CERTIFICATE The research titled ―Impact of Learning Environment of Cadet Colleges on Personality Development and Life Success of Students in Pakistan‖ is conducted under my supervision and thesis is submitted to The Islamia University of Bahawalpur in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education with my permission. Prof. Dr. Akhtar Ali ii APPROVAL CERTIFICATE This thesis titled ―Impact of Learning Environment of Cadet Colleges on Personality Development and Life Success of Students in Pakistan‖ written by Shahid Yaqub Abbasi is accepted and approved in the partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education. -

Hira Ovais.FH10

COMMUNITY AND ARCHITECTURE: CONTRIBUTION RETROSPECT IN KARACHI DURING THE BRITISH RAJ CASE OF SADDAR BAZAAR Hira Ovais* ABSTRACT ornamentation into local buildings were observed in many structures. Some of them were built by British architects Communities play a vital role in the development of any and engineers and others by the local firms under the British society, both in terms of political and commercial ambiance influence. and culture and social character, which contributes in the city formation. Karachi is an excellent example of it. Over This paper documents and analyses two such hybrid design the years the city has evolved from wilderness to being one buildings, which reflect the lifestyles of the communities of the most populous cities of the world. It houses many through the built form characteristics, details and formal imported traditions, which have mixed with local values and spatial characteristics. over the years. Keywords: Communities, Businessmen, Architects, Karachi, in 1900s was dominated by many ethnic Engineers, Ornamentation, Transformation communities, which resulted in the rise of a class system, which in turn lead to the emergence of communal enclaves INTRODUCTION to create a sense of communal values. Until independence of the sub-continent in 1947, these communities worked Cultural values of any city symbolize homogeneity and together and flourished in Karachi. uniqueness in its character. It helps us to understand physical, psychological and social importance of a historic area. In Saddar bazaar, the city centre of Karachi was mainly occupied Karachi, many of the Colonial buildings are still intact, and by these communities. Saddar was laid as a camp by the reflect the power of the once ruling British class. -

Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa White Paper Fiscal Year 2021-22

Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa White Paper Fiscal Year 2021-22 1 F O R E W O R D As I write this, I can really reflect on three years and say with conviction and a little bit of pride, that a change in financial management approach is helping to transform Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Having seen the amount of work that goes into budget making, I hope people will not mind if this message is a little bit personal. From a traditional culture of wanting to stop any kind of spend, to a culture of openness to manage the resources we have in the best way possible, the leaders in the finance department who have made this possible know who they are, and I am grateful to them. Secretary Atif Rehman, Special Secretaries Ayaz Khan and Shah Mahmood, and Additional Secretary Safeer Ahmed, who is the beating heart of the reform culture in the department; you should all be proud of how you have been leading a culture of change in financial management and setting standards for all of Pakistan. There are many more working in the department, too many to name, but the work you do is incredible. Similarly, our leadership at the Planning and Development department, our new Additional Chief Secretary (ACS) Shahab Ali Shah, Secretary Amir Tareen, Chief Economist Nauman Afridi; kudos on the very rapid transformation of the development budget from a traditional, department focused instrument to a dynamic, project focused instrument. You have built upon the work that outgoing ACS Shakeel Qadir Khan has done, and as a result, we perhaps have the most ambitious and most service delivery oriented Annual Development Programme ever. -

PIR ALI MUHAMMAD RASHDI COLLECTION English Books (Call No.: 900-999) S.No TITLE AUTHOR ACC:NO CALL NO

PIR ALI MUHAMMAD RASHDI COLLECTION English Books (Call No.: 900-999) S.No TITLE AUTHOR ACC:NO CALL NO. 1 Half Hours In Woods And Wilds Half hour library 5103 904 HAL 2 Tropic Adventure Rio Grande To Willard Price 6506 904.81072 PRI Patagonia 3 Western Civilization in The Near Easgt Hans Kohn 5374 909 KOH 4 Modern France F.C.Roe 5354 909.0944 ROE 5 The Dawn of Civilization Egypt And Gaston Maspero, Hon. 6370 909 MAS Chaldaea 6 The Civilization of The Renaissance In Jacob Burckhardt 5656 909.0945 BUR Italy 7 Re-Emerging Muslim World Zahid Malik 5307 909.091767 ZAH 8 The International Who's Who 1951 Europa Publications 5930 909.025 INT 9 The Arab Civilization Joseph Hell 5356 909.09174927- HEL 10 Enigmas of History Hugh Ross Williamson 5405 909.22 WIL 11 Ways of Medieval Lif e and Thought F.M.Powicke 5451 909.07 POW 12 Conventional Lies of Our Civilization Max Nordau 5090 909 NOR 13 The Civilization of The Ancient Bothwell Gosse 4994 909.0493 GOS Egyptians 14 A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Samuel Ball Platner 5093 910.309376 PLA Rome 15 Travel And Sport In Many Lands Major.P.M.Stewart 5311 910.202 STE 16 The Inner Life of Syria Palestine And Isabel Burton 6305 910.9569105694- the Holy Land BUR 17 Chambers's World Gazetter And T.C.Collocott 5848 910.3 COL Geographical Dictionary 18 Sport And Travel in India And Central A.G.Bagot 5228 910 BAG America 19 Lake Ngami: Or Explorations And Charles John Andersson 5193 910.96881 AND Discoveries 20 A King's Story Duke of Windsor 5780 910.084092 WIN 21 The Sky Is Italian Anthony Thorne 5755 914.5 THO 22 The Italian Lakes Gabriel Faure 5743 914.5 FAU 23 Wonders of Italy Joseph Fattorusso 6254 914.5 WON 24 An Historical Geography of Europe W.Gordon East 5268 914 GOR 25 Samoan Interlude Marie Tisdale Martin 6312 914.9582 MAR 26 The Imperial Gazetter of India.