Colonial Encounters, Karachi and Anglo-Indian Dwellings During the Raj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

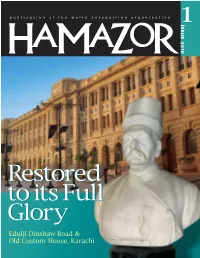

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Diagnostic Centers'!A1 Laboratories!A1 Dental Centers'!A1 Ophthalmology Clinics'!A1 Medical Center'!A1 Diagnostic Centers

Diagnostic Centers'!A1 Laboratories!A1 Dental Centers'!A1 Ophthalmology Clinics'!A1 Medical Center'!A1 Diagnostic Centers L I S T O F A L L I A N Z E F U N E T W O R K D I S C O U N T D I A G N O S T I C C E N T R E S S.No Hospital Name Address Contact Contact Person Email Contact Number City Discount Category 021-35662052 Mr. Yousuf Poonawala 1 Burhani Diagnostic Centre Jaffer Plaza, Mansfield Street, Saddar, Karachi. 021-5661952 Karachi 10-15% Diagnostic Center 0336-0349355 (Administrator) [email protected] 02136626125-6 0334-3357471 [email protected] 2 Dr. Essa's Laboratory & Diagnostic Centre (Main Centre) B-122 (Blue Building) Block-H, Shahrah-e-Jahangir, Near Five Star, North Nazimabad. Mr. Shakeel / Ms. Shahida 021-36625149 Karachi 10-20% Diagnostic Center 0335-5755529 [email protected] 021-36312746 0335- 2.1 Ayesha Manzil Centre Ali Appartment, FB Area Karachi Karachi 10-20% Diagnostic Center 5755536 021-35862522 021- 2.2 Zamzama Centre Suite # 2, Plot 8-C (Beside Aijaz Boutique), 4th Zamzama Commercial Lane Karachi 10-20% Diagnostic Center 35376887 2.3 Medilink Centre Suite # 103, 1st Floor, The Plaza, 2 Talwar, Khayaban-e-Iqbal, Main Clifton Road, Karachi 021-35376071-74 Karachi 10-20% Diagnostic Center 2.4 Abdul Hassan Isphahani Centre A-1/3&4, Block-4, gulshan-e-Iqbal. Main Abdul Hassan Isphahani Road, Karachi 021-34968377-78 Karachi 10-20% Diagnostic Center 2.5 KPT Centre Karachi Port Trust Hospital Keemari, Karachi 021-34297786 Karachi 10-20% Diagnostic Center 021-34620176 021- 2.6 Gulistan-E-Johar Centre S -

12086393 01.Pdf

Exchange Rate 1 Pakistan Rupee (Rs.) = 0.871 Japanese Yen (Yen) 1 Yen = 1.148 Rs. 1 US dollar (US$) = 77.82 Yen 1 US$ = 89.34 Rs. Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Karachi Transportation Improvement Project ................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Background................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1.2 Work Items ................................................................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.3 Work Schedule ........................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.2 Progress of the Household Interview Survey (HIS) .......................................................................... 1-5 1.3 Seminar & Workshop ........................................................................................................................ 1-5 1.4 Supplementary Survey ....................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.4.1 Topographic and Utility Survey................................................................................................. 1-6 1.4.2 Water Quality Survey ............................................................................................................... -

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

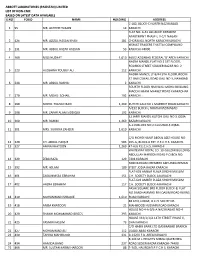

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND30284 Country: India Date: 4 July 2006 Keywords: India – Maharashtra – Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? 2. Is there any information about the authorities’ position on any ill-treatment of Sindhi people? RESPONSE 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? Executive Summary Information available on Sindhi websites, in press reports and in academic studies suggests that, generally speaking, the Sindhi community in Maharashtra state are not ill-treated. Most writers who address the situation of Sindhis in Maharashtra generally concern themselves with the social and commercial success which the Sindhis have achieved in Mumbai (where the greater part of the Sindh’s Hindu populace relocated after the partition of India and Pakistan). One news article was located which reported that the Sindhi community had been targeted for extortion, along with other “mercantile communities”, by criminal networks affiliated with Maharashtra state’s Sihiv Sena organisation. -

Migration from Bengal to Arakan During British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin

Occasional Paper Series Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin 2019 Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher Brussels This and other publications in TOAEP’s Occasional Paper Series may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site http://toaep.org, which uses Persistent URLs for all publications it makes available (such PURLs will not be changed). This publication was first published on 6 December 2019. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2019 All rights are reserved. You may read, print or download this publication or any part of it from http://www.toaep.org/ for personal use, but you may not in any way charge for its use by others, directly or by reproducing it, storing it in a retrieval system, transmitting it, or utilising it in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, in whole or in part, without the prior permis- sion in writing of the copyright holder. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the copyright holder. You must not circulate this publication in any other cover and you must impose the same condition on any ac- quirer. You must not make this publication or any part of it available on the Internet by any other URL than that on http://www.toaep.org/, without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-82-8348-150-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 2 2. Setting the Scene: The 1911, 1921 and 1931 Censuses of British Burma ............................ -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Annexures for Annual Report 2020

List of Annexures Annex A Minutes of the Annual General Meeting held on March 08, 2019 Annex B Detailed Expenditures on Purchase and Establishment of PCATP Head Office Islamabad Annex C Policy guidelines for Online Teaching-Learning and Assessment Implementation Annex D Thesis guidelines for graduating batch during COVID-19 pandemic Annex E Inclusion of PCATP in NAPDHA Annex F Inclusion of role of Architects and Town Planners in the CIDB Bill 2020 Annex G Circulation List for Compliance of PCATP Ordinance IX of 1983 Annex H Status of Institutions Offering Architecture and Town Planning Undergraduate Degree Programs in Pakistan Annex I List of Registered Members and Firms who have contributed towards COVID- 19 fund in PCATP Account Annex J List of Registered Members and Firms who have contributed towards COVID- 19 fund in IAP Account Audited Accounts and Balance Sheet of PCATP General Fund and RHS Annex K Account for the Year 2018-2019 Page | 1 ANNEX A MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE PAKISTAN COUNCIL OF ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS ON FRIDAY, 8th MARCH, 2019, AT RAMADA CREEK HOTEL, KARACHI. In accordance with the notice, the Annual General Meeting of the Pakistan Council of Architects and Town Planners was held at 1700 hrs on Friday, 8th March, 2019 at Crystal Hall, Ramada Creek Hotel, Karachi, under the Chairmanship of Ar. Asad I. A. Khan. 1.0 AGENDA ITEM NO.1 RECITATION FROM THE HOLY QURAN 1.1 The meeting started with the recitation of Holy Quran, followed by playing of National Anthem. 1.2 Ar. FarhatUllahQureshi proposed that the house should offer Fateha for PCATP members who have left us for their heavenly abode. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

Annual Report 2019 03 Report of the Managing Committee

Annual Overseas Investors Chamber of Report Commerce and Industry 2019 Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah addressing members at Chamber's Annual Conference in 1948 Vision To be the premier body for promoting new and existing overseas investment in Pakistan by leveraging world-class expertise of OICCI members for the benefit of the investors and the country Mission • To assist in fostering a conducive, open and equitable business environment in Pakistan • To facilitate the transfer of best global practices to Pakistan • To enhance the image of overseas investors in Pakistan and of the country abroad 02 OICCI Profile 04 Report of the Managing Committee 08 Managing Committee Members 2019 Contents 02. OICCI Profile 10 04. Report of the Managing Committee 08. Managing Committee Members 2019 Summary of OICCI 10. Summary of OICCI Activities 2019 Activities 2019 a) Policy Reform and Advocacy b) Investment Promotion c) Profile Building and Networking d) Information Dissemination 37 e) OICCI’s Representation on Various Bodies Financial Statements 37. Financial Statements 54. Notice of the 160th Annual General Meeting 56. Meetings of the Managing Committee 57. List of OICCI Members 54 Notice of the 160th Annual General Meeting 56 Meetings of the Managing Committee 57 List of OICCI Members OICCI Profile The Overseas Investors Chamber of Commerce and Industry (OICCI) is the collective voice of major foreign investors in Pakistan. Established 160 years ago in 1860, primarily as a business chamber for foreign investors, the OICCI is engaged in promoting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Pakistan, besides protecting the interest of existing foreign investors/OICCI members.