Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

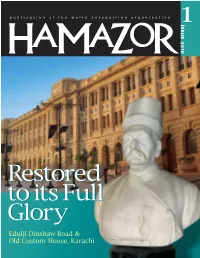

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Pakistan Was Suspended by President General Musharaff in March Last Year Leading to a Worldwide Uproar Against This Act

A Coup against Judicial Independence . Special issue of the CJEI Report (February, 2008) ustice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, the twentieth Chief Justice of Pakistan was suspended by President General Musharaff in March last year leading to a worldwide uproar against this act. However, by a landmark order J handed down by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, Justice Chaudhry was reinstated. We at the CJEI were delighted and hoped that this would put an end to the ugly confrontation between the judiciary and the executive. However our happiness was short lived. On November 3, 2007, President General Musharaff suspended the constitution and declared a state of emergency. Soon the Pakistan army entered the Supreme Court premises removing Justice Chaudhry and other judges. The Constitution was also suspended and was replaced with a “Provisional Constitutional Order” enabling the Executive to sack Chief Justice Chaudhry, and other judges who refused to swear allegiance to this extraconstitutional order. Ever since then, the judiciary in Pakistan has been plunged into turmoil and Justice Chaudhry along with dozens of other Justices has been held incommunicado in their homes. Any onslaught on judicial independence is a matter of grave concern to all more so to the legal and judicial fraternity in countries that are wedded to the rule of law. In the absence of an independent judiciary, human rights and constitutional guarantees become meaningless; the situation capable of jeopardising even the long term developmental goals of a country. As observed by Viscount Bryce, “If the lamp of justice goes out in darkness, how great is the darkness.” This is really true of Pakistan which is presently going through testing times. -

Political Development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the Elections of 1970

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1973 Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970. Meenakshi Gopinath University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Gopinath, Meenakshi, "Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970." (1973). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2461. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2461 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIVE COLLEGE DEPOSITORY POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS June 1973 Political Science POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Approved as to style and content hy: Prof. Anwar Syed (Chairman of Committee) f. Glen Gordon (Head of Department) Prof. Fred A. Kramer (Member) June 1973 ACKNOWLEDGMENT My deepest gratitude is extended to my adviser, Professor Anwar Syed, who initiated in me an interest in Pakistani poli- tics. Working with such a dedicated educator and academician was, for me, a totally enriching experience. I wish to ex- press my sincere appreciation for his invaluable suggestions, understanding and encouragement and for synthesizing so beautifully the roles of Friend, Philosopher and Guide. -

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President 1885 Bombay W.C. Bannerji 1886 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1887 Madras Syed Badruddin Tyabji 1888 Allahabad George Yule First English president 1889 Bombay Sir William 1890 Calcutta Sir Pherozeshah Mehta 1891 Nagupur P. Anandacharlu 1892 Allahabad W C Bannerji 1893 Lahore Dadabhai Naoroji 1894 Madras Alfred Webb 1895 Poona Surendranath Banerji 1896 Calcutta M Rahimtullah Sayani 1897 Amraoti C Sankaran Nair 1898 Madras Anandamohan Bose 1899 Lucknow Romesh Chandra Dutt 1900 Lahore N G Chandravarkar 1901 Calcutta E Dinsha Wacha 1902 Ahmedabad Surendranath Banerji 1903 Madras Lalmohan Ghosh 1904 Bombay Sir Henry Cotton 1905 Banaras G K Gokhale 1906 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1907 Surat Rashbehari Ghosh 1908 Madras Rashbehari Ghosh 1909 Lahore Madanmohan Malaviya 1910 Allahabad Sir William Wedderburn 1911 Calcutta Bishan Narayan Dhar 1912 Patna R N Mudhalkar 1913 Karachi Syed Mahomed Bahadur 1914 Madras Bhupendranath Bose 1915 Bombay Sir S P Sinha 1916 Lucknow A C Majumdar 1917 Calcutta Mrs. Annie Besant 1918 Bombay Syed Hassan Imam 1918 Delhi Madanmohan Malaviya 1919 Amritsar Motilal Nehru www.bankersadda.com | www.sscadda.com| www.careerpower.in | www.careeradda.co.inPage 1 1920 Calcutta Lala Lajpat Rai 1920 Nagpur C Vijaya Raghavachariyar 1921 Ahmedabad Hakim Ajmal Khan 1922 Gaya C R Das 1923 Delhi Abul Kalam Azad 1923 Coconada Maulana Muhammad Ali 1924 Belgaon Mahatma Gandhi 1925 Cawnpore Mrs.Sarojini Naidu 1926 Guwahati Srinivas Ayanagar 1927 Madras M A Ansari 1928 Calcutta Motilal Nehru 1929 Lahore Jawaharlal Nehru 1930 No session J L Nehru continued 1931 Karachi Vallabhbhai Patel 1932 Delhi R D Amritlal 1933 Calcutta Mrs. -

Pakistan Studies) Courses

PAKISTAN STUDY CENTRE, UNIVERSITY OF SINDH, JAMSHORO M.PHIL (PAKISTAN STUDIES) COURSES Course work required for M.Phil (Pakistan Studies) is consisted of the following six courses-two semester. The credit hours for each course are given below: Paper Course Title of the Course Credit Marks No. Hours 1ST SEMESTER I PSC-800 Studies on Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah 4 100 II PSC-801 Political Parties in Pakistan 4 100 III PSC-802 Pakistan and the World 4 100 IV PSC-803 Research Methodology 4 100 2ND SEMESTER V PSC-804 Studies on the Freedom Fighters 4 100 VI PSC-805 Studies on Subsidiary Movements of Indo-Pak 4 100 - 1 - PAKISTAN STUDY CENTRE, UNIVERSITY OF SINDH, JAMSHORO STUDIES ON QUAID-I-AZAM MOHAMMAD ALI JINNAH M.PHIL PAKISTAN STUDIES The course will focus on the life, career and his struggle for a separate homeland of Muslims with special reference to his role as a parliamentarian, politician, leader of masses, nation builder, ideologue and his vision for Pakistan. COURSE NO.PSC-800 PAPER-I 1ST SEMESTER Family Background & Early Lifep 1. Family background and Birth of Jinnah 2. Early Education 3. Karachi 4. Bombay 5. Karachi 6. Marriage Education in London 1. Lincoln's Inn, London 2. Life in England 3. Early Influences As A Barrister 1. As a Barrister and Advocate of Bombay High Court 1896 2. Entry into Politics 1897-1906 Emergence as an All-India Leader 1906-1913 1. His Role in the Congress 2. Pleads Muslim Waqf Issue 3. Joining All-India Muslim League Leader of Both Congress and the Muslim League 1913-1920 1. -

The Khilafat Movement in India 1919-1924

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 62 THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 A. C. NIEMEIJER THE HAGUE - MAR TINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1334.X PREFACE The first incentive to write this book originated from a post-graduate course in Asian history which the University of Amsterdam organized in 1966. I am happy to acknowledge that the university where I received my training in the period from 1933 to 1940 also provided the stimulus for its final completion. I am greatly indebted to the personal interest taken in my studies by professor Dr. W. F. Wertheim and Dr. J. M. Pluvier. Without their encouragement, their critical observations and their advice the result would certainly have been of less value than it may be now. The same applies to Mrs. Dr. S. C. L. Vreede-de Stuers, who was prevented only by ill-health from playing a more active role in the last phase of preparation of this thesis. I am also grateful to professor Dr. G. F. Pijper who was kind enough to read the second chapter of my book and gave me valuable advice. Beside this personal and scholarly help I am indebted for assistance of a more technical character to the staff of the India Office Library and the India Office Records, and also to the staff of the Public Record Office, who were invariably kind and helpful in guiding a foreigner through the intricacies of their libraries and archives. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Flashpoint: Pakistan in Crisis

To approach Rabwah, home to Pakistan’s minority Ahmadi sect, it is necessary to pass through Chiniot, an ancient town said to have been first populated by Alexander the Great of Macedonia, in 326 BC . Today, Chiniot, which stands amidst the lush green countryside of the Punjab province, is known chiefly for its skilled furniture craftsmen. The town is a bustling, but run-down urban centre – the cascading monsoon rain failing to wash away the grime and squalor that hangs all around. It is on the peeling, yellow-plastered walls of Chiniot that the first signs of the hatred directed against the Ahmadi community appear. The movement – named for its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian (located in the Indian Punjab) – Karachi broke away from mainstream Islam in 1889. The slogans, etched out in the flowing Urdu script, call on Muslims to ‘Kill Ahmadi non-believers’. apparent every official building is heavily fortified – Rabwah, a town of some 50,000 people, houses even the holy places and the parks – testifying to the the largest concentration of Ahmadis in Pakistan. fact that Rabwah remains a town under siege. Flashpoint Overall, there are an estimated 1.5 million Ahmadis While the 1974 decision against Ahmadis was met in the country amongst a population of 55 million by anger within the community, worse was to come. In people. Rabwah was built on 1,000 acres of land 1984, military dictator General Zia ul-Haq, as part of purchased from the Pakistan government in 1948 by policies aimed at ‘Islamizing’ the country, introduced a Pakistan in Crisis: the Ahmaddiya Muslim community, to house set of laws that, among other restrictions, barred Ahmadis who were forced to leave India amidst the Ahmadis from preaching their faith, calling their places tumultuous partition of the subcontinent in 1947, of worship ‘masjids’ (the term used by mainstream which resulted in the creation of the mainly Muslim Muslims) and from calling themselves Muslim. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

September 2017

SPECIAL FEATURE HH Prince Karim Aga Khan 2017 Reg. ss-973 September INSIDE AFGHANISTAN PAKISTAN INDIA NEIGHBOUR Whither War? New Wine in New Bottles Birth of a New Axis Border Trouble Revolving Door The office of the Prime Minister in Pakistan seems to have a revolving door that prime ministers use to vacate their office before their term is up. Why does this happen? Contents 12 Mujhe KiyunNikala? No prime minister has completed his term in Pakistan. Afghanistan Whither War? A new U.S. policy to 28 end the war. Pakistan Sri Lanka 22 Back to Square One New Wine in Inviting the Tamils back. New Bottles 30 Trump is for loans, not aid. The Maldives Rabbit Hole of Dictatorship 32 Democratically elected president tries iron hand. 26 Bangladesh Limping Judiciary Legal tussle in a country where democracy is supposed to be supreme. 4 SOUTHASIA • SEPTEMBER 2017 REGULAR FEATURES Editor’s Mail 8 On Record 9 Briefs 10 COVER STORY Mujhe Kiyun Nikala? 12 Term Stinted 14 The Judiciary’s Role 16 Legacy of Failure 18 REGION India Birth of a New Axis 20 Pakistan New Wine in New Bottles 22 All In The Family 24 42 Bangladesh International Limping Judiciary 26 Canadian Politics Afghanistan The other side of Trudeau. Whither War? 28 Sri Lanka Back to Square One 30 The Maldives Rabbit Hole of Dictatorship 32 OPINION 54 Pakistan at 70 – A Personal Perspective 34 Crime SPECIAL FEATURE Wronged Women Bangladeshi women HH Prince Karim Aga Khan 37 need more security. INTERNATIONAL The Reluctant Prime Minister 42 NEIGHBOUR Forgotten People 44 Infrastructure FEATURES Bridge of Gender Equality Determination What’s in a Name! 48 The Padma Bridge is fast 50 nearing completion. -

ESMP-KNIP-Saddar

Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Development Department, Government of Sindh Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject Karachi Neighborhood Improvement Project (P161980) Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) October 2017 Environmental and Social Management Plan Final Report Executive Summary Government of Sindh with the support of World Bank is planning to implement “Karachi Neighborhood Improvement Project” (hereinafter referred to as KNIP). This project aims to enhance public spaces in targeted neighborhoods of Karachi, and improve the city’s capacity to provide selected administrative services. Under KNIP, the Priority Phase – I subproject is Educational and Cultural Zone (hereinafter referred to as “Subproject”). The objective of this subproject is to improve mobility and quality of life for local residents and provide quality public spaces to meet citizen’s needs. The Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject ESMP Report is being submitted to Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Development Department, Government of Sindh in fulfillment of the conditions of deliverables as stated in the TORs. Overview the Sub-project Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject forms a triangle bound by three major roads i.e. Strachan Road, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road and M.R. Kayani Road. Total length of subproject roads is estimated as 2.5 km which also forms subproject boundary. ES1: Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject The following interventions are proposed in the subproject area: three major roads will be rehabilitated and repaved and two of them (Strachan and Dr Ziauddin Road) will be made one way with carriageway width of 36ft. -

Notification

GOVERNMENT OF SINDH SERVICES, GENERAL ADMINISTRATION & COORDINATION DEPARTMENT Karachi, dated 1 November, 2006 NOTIFICATION NO.SO(C-I)SGA&CD/4-80/06 : The Government of Sindh is pleased to adopt the Public Procurement Regularity Authority (PPRA), Public Procurement Rules 2004 with immediate effect and till further orders to improve transparency in procurement of goods, services and consultancies. Accordingly following guide lines are issued for strict compliance by all departments/attached departments, autonomous semi autonomous bodies, all offices and subordinate offices of the Sindh Government, District Governments/TMAs/UCs and all establishments associated with Government of Sindh. a) The Public Procurement Rules 2004 shall have overriding effect on all existing Procurement Rules, Regulations, Manuals, Instructions / Orders issued by the Government from time to time and shall apply to all departments, District Governments, autonomous, semi autonomous organizations / commissions and all offices being paid directly and indirectly out of or through finances of Govt. of Sindh. b) All tenders, as required under PPRA, Public Procurement Rules 2004 bidding documents, processing of bidding documents and final decisions taken by the procuring departments / officers of Government of Sindh including District Governments must be placed on the website of the Government of Sindh www.sindh.gov.pk Any violation by any department / authority / officer in the matter would result in invalidation / cancellation of such tender and responsible officer to be proceeded under relevant disciplinary laws of the Government of Sindh. c) The practice of enlisting and registration of contractors and suppliers by departments / district governments and government agencies / semi government agencies authorities is stopped with immediate effect and in future all intending participants may bid for the tenders and final decision may be made by procuring authorities after analysis, evaluation and vetting of the technical and financial proposals.