Public and Private Control and Contestation of Public Space Amid Violent Conflict in Karachi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dispositifs of (Dis)Order: Gangs, Governmentality and the Policing of Lyari, Pakistan Adeem Suhail

Dispositifs of (Dis)Order: Gangs, governmentality and the policing of Lyari, Pakistan Adeem Suhail Abstract: At a moment when the violence of policing has found its locus in the bureaucratic institutions of ‘the police’, anthropology offers a more expansive idea of policing as a social function, articulated through multiple social forms, and crucial to hierarchical orders. This article draws on the idea of the dispositif to offer a processual model for understanding how non-state violence abets the maintenance of social order. Exploring the limits of biopolitics and drawing on ethnographic evidence, it uses the case of gang activity in Lyari, Pakistan, to show how gangsters maintained, rather than disrupt, the dominant social order in the city. Furthermore, it shows that those who challenged the inherently violent and exploitative order implemented by the gangs and the city's political elite were prime targets of public violence wielded by law and outlaw working together as a dispositif. Introduction The policeman who collected him from the recycling depot did not offer any explanations which made Babu Maheshwari apprehensive. Things became clearer when a few blocks away they arrived at the drainage nala. Babu saw the boy floating face-down in the murky waters amidst the thick sludge of excreta, plastics, chemicals, and once-desired objects that form Karachi’s daily discharge. This mundanely repugnant ecology had claimed and begun consuming the boy. Babu, a veteran municipal waste worker hailing from the ex-untouchable Dalit communities of coastal Sind, was brung, once more, to be the instrument that reclaimed the body, as a once-desired object, now discarded by city into its rivers of shit. -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Huma Yusuf 1 EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 21 June 2013 1. Th e author thanks Jahanzaib Haque and Individualland Pakistan for their help with researching this report. Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Central-Karachi

Central-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 1-Kalyana 408130186 GBELS - Elementary Elementary Boys 20,253 4,051 16,202 4,051 4,051 16,202 64,808 16,202 81,010 2 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130163 GBLSS - 11-G NEW KARACHI Middle Boys 24,147 4,829 19,318 4,829 4,829 19,318 77,271 19,318 96,589 3 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130167 GBLSS - MEHDI Middle Boys 11,758 2,352 9,406 2,352 2,352 9,406 37,625 9,406 47,031 4 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130176 GBELS - MATHODIST Elementary Boys 20,492 4,098 12,295 8,197 4,098 16,394 65,576 16,394 81,970 5 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 6-Hakim Ahsan 408130205 GBELS - PIXY DALE 2 Registred as a Seconda Elementary Girls 61,338 12,268 49,070 12,268 12,268 49,070 196,281 49,070 245,351 6 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 9-Khameeso Goth 408130174 GBLSS - KHAMISO GOTH Middle Mixed 6,962 1,392 5,569 1,392 1,392 5,569 22,278 5,569 27,847 7 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130160 GBLSS - FARZANA Middle Boys 11,678 2,336 9,342 2,336 2,336 9,342 37,369 9,342 46,711 8 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130166 GBLSS - 5/J Middle Boys 28,064 5,613 16,838 11,226 5,613 22,451 89,804 22,451 112,256 9 Central Karachi New Karachi -

12086393 01.Pdf

Exchange Rate 1 Pakistan Rupee (Rs.) = 0.871 Japanese Yen (Yen) 1 Yen = 1.148 Rs. 1 US dollar (US$) = 77.82 Yen 1 US$ = 89.34 Rs. Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Karachi Transportation Improvement Project ................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Background................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1.2 Work Items ................................................................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.3 Work Schedule ........................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.2 Progress of the Household Interview Survey (HIS) .......................................................................... 1-5 1.3 Seminar & Workshop ........................................................................................................................ 1-5 1.4 Supplementary Survey ....................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.4.1 Topographic and Utility Survey................................................................................................. 1-6 1.4.2 Water Quality Survey ............................................................................................................... -

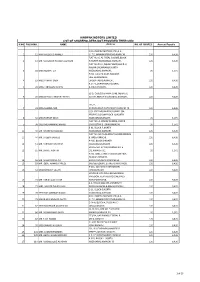

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-E - Faisal

S No Cities TCS Offices Address Contact 1 Karachi TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-e - Faisal. 0316-9992201 2 Karachi TCS Office Main Head 101-104 CAA Club Road Near Hajj Tarminal - 3 0316-9992202 3 Karachi TCS Office Malir Cantt Shop#180 S-13 Cantt Bazar, Malir Cantonement, Karachi 0316-9992204 4 Karachi TCS Office Malir Court Shop # G-14 Al Raza Sq. New Malir City Near Malir Court 0316-9992207 Shop # 3Haq Baho shopping Center Gulshan e Hadeed Ph.1 Gulshan e 5 Karachi TCS Office Gulshan-E-Hadeed 0316-9992213 Hadeed 6 Karachi TCS Office Korangi No. 4 Shop # 10, Abbasi Fair Trade Centre, Korangi # 4 Opp. KMC Zoo 0316-9992215 7 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN Chowrangi Shop A 1/30, block No 5. Haider plaza gulshan-e-Iqbal Karachi 0316-9992230 8 Karachi TCS Office GULISTAN-E-JOHAR Shop # Saima Classic Rashid Minas Road Near Johar More 0316-9992231 9 Karachi TCS Office HYDRI Shop # B-13, Al Bohran Circle, Block-B, North Nazimabad. 0316-9992232 10 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN-E-IQBAL Shop # 06, Plot # B-74 Shelzon Center BI.15 Opp. Usmania Restrent 0316-9992234 11 Karachi TCS Office ORANGI TOWN Banaras Town, Sector 8, Orangi Town Karachi Opp. Banaras Town Masjid 0316-9992236 12 Karachi TCS Office S.I.T.E Shop # 5, SITE Shopping Centre, Manghopir Rd. Opp. MCB SITE Br. 0316-9992237 13 Karachi TCS Office NIPA CHOWRANGI Shop # A -8 KDA Overseas apartment 0316-9992241 S 5 Noman Arcade Bl. 14 Gulshan-e-Iqbal Near Mashriq Centre Sir 14 Karachi TCS Office Mashriq Center 0316-9992250 suleman shah Rd. -

Pdf (Accessed: 3 June, 2014) 17

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 The Production and Reception of gender- based content in Pakistani Television Culture Munira Cheema DPhil Thesis University of Sussex (June 2015) 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted, either in the same or in a different form, to this or any other university for a degree. Signature:………………….. 3 Acknowledgements Special thanks to: My supervisors, Dr Kate Lacey and Dr Kate O’Riordan, for their infinite patience as they answered my endless queries in the course of this thesis. Their open-door policy and expert guidance ensured that I always stayed on track. This PhD was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. My mother, for providing me with profound counselling, perpetual support and for tirelessly watching over my daughter as I scrambled to meet deadlines. This thesis could not have been completed without her. My husband Nauman, and daughter Zara, who learnt to stay out of the way during my ‘study time’. -

Statement of Ali Dayan Hasan Pakistan Director, Human Rights Watch

Statement of Ali Dayan Hasan Pakistan Director, Human Rights Watch: House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations February 8, 2012 Hearing on Balochistan Balochistan: An overview Balochistan, Pakistan’s western-most province, borders eastern Iran and southern Afghanistan. It is the largest of the country’s four provinces in terms of area (44 percent of the country’s land area), but the smallest in terms of population (5 percent of the country’s total). According to the last national census in 1998, over two-thirds of its population of nearly eight million people live in rural areas.1 The population comprises those whose first language—an important marker of ethnic distinction in Pakistan—is Balochi (55 percent), Pashto (30 percent), Sindhi (5.6 percent), Seraki (2.6 percent), Punjabi (2.5 percent), and Urdu (1 percent).2 There are three distinct geographic regions of Balochistan. The belt comprising Hub, Lasbella, and Khizdar in the east is heavily influenced by the city of Karachi, Pakistan’s sprawling economic center in Sindh province. The coastal belt comprising Makran is dominated by Gwadar port. Eastern Balochistan is the most remote part of the province. This sparsely populated region is home to the richest but largely untapped deposits of natural resources in Pakistan including oil, gas, copper, and gold. Significantly, it is the area where the struggle for power between the Pakistani state and local tribal elites has been most apparent.3 Balochistan is both economically and strategically important: not only does the province border Iran and Afghanistan, it hosts a particular ethnic mix of residents, and is allegedly home to the so-called Quetta Shura of the Taliban in the provincial capital Quetta.4 The situation is further complicated by the large number of foreign states with an economic or 1 Census of Pakistan 1998, Balochistan Provincial Report; and World Bank, Balochistan Economic Report: From Periphery To Core, Volume II, 2008. -

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR. -

PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST a Selected Summary of News, Views and Trends from Pakistani Media

April 2015 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST A Selected Summary of News, Views and Trends from Pakistani Media Prepared by YaqoobulHassan and Shreyas Deshmukh (Interns, Pakistan Project, IDSA) PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST APRIL 2015 A Select Summary of News, Views and Trends from the Pakistani Media Prepared by Yaqoob ul Hassan (Pakistan Project, IDSA) INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES 1-Development Enclave, Near USI Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 Pakistan News Digest, April 2015 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST, APRIL 2015 CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................. 0 ABBRIVATIONS ............................................................................................. 2 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS .......................................................................... 3 PROVINCIAL POLITICS ................................................................................ 3 OTHER DEVELOPMENTS ............................................................................ 7 FOREIGN POLICY ...............................................................................................11 MILITARY AFFAIRS ...........................................................................................18 EDITORIALS AND OPINIONS ........................................................................21 ECONOMIC ISSUES ...........................................................................................31 FISCAL ISSUES ............................................................................................ -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity.