Kurrachee (Karachi) Past: Present and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

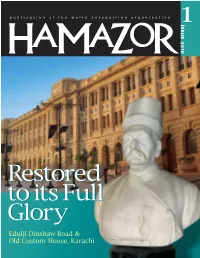

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools JUL 0 2 2003

Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri B.S. Architecture Studies University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2001 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2003 JUL 0 2 2003 Copyright@ 2003 Mahjabeen Quadri. Al rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Mahjabeen Quadri Departm 4t of Architecture, May 19, 2003 Certified by:- Reinhard K. Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Julian Beinart Departme of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students ROTCH Thesis Committee Reinhard Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Edith Ackermann Visiting Professor Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Anna Hardman Visiting Lecturer in International Development Planning Department of Urban Studies and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Hashim Sarkis Professor of Architecture Aga Khan Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism Harvard University Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 23, 2003 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract Pakistan's greatest resource is its children, but only a small percentage of them make it through primary school. -

THE USE of WOOD for AIRCRAFT in Tilt UNITED KINGDOM Report of the Forest Products Mission

THE USE Of WOOD FOR AIRCRAFT IN Tilt UNITED KINGDOM Report of the forest Products Mission June 1944 ( No. 1540 ) UNITED STATES REPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE \FOREST SERVICE OREST RODUCTS LABORATORY Madison, Wisconsin In Cooperation with the University of Wisconsin r%; Y 1 4 9 14. \ THE.USE OF WOOD FOR AIRCRAFT IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Report of the Forest Products Mission INTRODUCTION On July 2, 1943, the British Air Commission in Washington, D, C., on behalf of the Ministry of Aircraft Production extended to the Secretary of the U. S. Department of Agriculture an invitation for representatives of the Forest Products Laboratory to visit England for the purpose of "strengthening the present collaboration between our two countries on researches into the uses of timber in aircraft construction." The Secretar: of Agriculture accepted this invitation. At the same time, similar invitations were extended by the British Air Commission to the U. S. Army Air Forces, the U. S. Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, the U. S. Civil Aeronautics Administration, and to the Canadian Forest Products Laboratories. Due to pressure of work and limi- tation of technical personnel, the Army and Navy were unable to accept the invitation. As finally constituted, the participants in the group, hereinafter referred to as the Forest Products Mission, were as follows: United States Carlile P. Winslow, Director, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin, Chairman of the Mission. L. J. Markwardt, Assistant Director, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin. Thomas R. Truax, Principal Wood Technologist, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin. Charles B. Norris, Principal Engineer, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin. -

Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND30284 Country: India Date: 4 July 2006 Keywords: India – Maharashtra – Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? 2. Is there any information about the authorities’ position on any ill-treatment of Sindhi people? RESPONSE 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? Executive Summary Information available on Sindhi websites, in press reports and in academic studies suggests that, generally speaking, the Sindhi community in Maharashtra state are not ill-treated. Most writers who address the situation of Sindhis in Maharashtra generally concern themselves with the social and commercial success which the Sindhis have achieved in Mumbai (where the greater part of the Sindh’s Hindu populace relocated after the partition of India and Pakistan). One news article was located which reported that the Sindhi community had been targeted for extortion, along with other “mercantile communities”, by criminal networks affiliated with Maharashtra state’s Sihiv Sena organisation. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

Chronologica Dictionary of Sind Chronologial Dictionary of Sind

CHRONOLOGICA DICTIONARY OF SIND CHRONOLOGIAL DICTIONARY OF SIND (From Geological Times to 1539 A.D.) By M. H. Panhwar Institute of Sindhology University of Sind, Jamshoro Sind-Pakistan All rights reserved. Copyright (c) M. H. Panhwar 1983. Institute of Sindhology Publication No. 99 > First printed — 1983 No. of Copies 2000 40 0-0 Price ^Pt&AW&Q Published By Institute of Sindhlogy, University of Sind Jamshoro, in collabortion with Academy of letters Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Education Islamabad. Printed at Educational Press Dr. Ziauddin Ahmad Road, Karachi. • PUBLISHER'S NOTE Institute of Sindhology is engaged in publishing informative material on - Sind under its scheme of "Documentation, Information and Source material on Sind". The present work is part of this scheme, and is being presented for benefit of all those interested in Sindhological Studies. The Institute has already pulished the following informative material on Sind, which has received due recognition in literary circles. 1. Catalogue of religious literature. 2. Catalogue of Sindhi Magazines and Journals. 3. Directory of Sindhi writers 1943-1973. 4. Source material on Sind. 5. Linguist geography of Sind. 6. Historical geography of Sind. The "Chronological Dictionary of Sind" containing 531 pages, 46 maps 14 charts and 130 figures is one of such publications. The text is arranged year by year, giving incidents, sources and analytical discussions. An elaborate bibliography and index: increases the usefulness of the book. The maps and photographs give pictographic history of Sind and have their own place. Sindhology has also published a number of articles of Mr. M.H. Panhwar, referred in the introduction in the journal Sindhology, to make available to the reader all new information collected, while the book was in press. -

ESMP-KNIP-Saddar

Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Development Department, Government of Sindh Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject Karachi Neighborhood Improvement Project (P161980) Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) October 2017 Environmental and Social Management Plan Final Report Executive Summary Government of Sindh with the support of World Bank is planning to implement “Karachi Neighborhood Improvement Project” (hereinafter referred to as KNIP). This project aims to enhance public spaces in targeted neighborhoods of Karachi, and improve the city’s capacity to provide selected administrative services. Under KNIP, the Priority Phase – I subproject is Educational and Cultural Zone (hereinafter referred to as “Subproject”). The objective of this subproject is to improve mobility and quality of life for local residents and provide quality public spaces to meet citizen’s needs. The Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject ESMP Report is being submitted to Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Development Department, Government of Sindh in fulfillment of the conditions of deliverables as stated in the TORs. Overview the Sub-project Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject forms a triangle bound by three major roads i.e. Strachan Road, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road and M.R. Kayani Road. Total length of subproject roads is estimated as 2.5 km which also forms subproject boundary. ES1: Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject The following interventions are proposed in the subproject area: three major roads will be rehabilitated and repaved and two of them (Strachan and Dr Ziauddin Road) will be made one way with carriageway width of 36ft. -

The Role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement in Sindhi-Muhajir Controversy in Pakistan

ISSN: 2664-8148 (Online) Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (LASSIJ) https://doi.org/10.47264/idea.lassij/1.1.2 Vol. 1, No. 1, (January-June) 2017, 71-82 https://www.ideapublishers.org/lassij __________________________________________________________________ The Role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement in Sindhi-Muhajir Controversy in Pakistan Syed Mukarram Shah Gilani1*, Asif Salim1-2 and Noor Ullah Khan1-3 1. Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, Peshawar Pakistan. 2. Department of Political Science, Emory University Atlanta, Georgia USA. 3. Department of Civics-cum-History, FG College Nowshera Cantt., Pakistan. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Abstract The partition of Indian sub-continent in 1947 was a historic event surrounded by many controversies and issues. Some of those ended up with the passage of time while others were kept alive and orchestrated. Besides numerous problems for the newly born state of Pakistan, one such controversy was about the Muhajirs (immigrants) who were settled in Karachi. The paper analyses the factors that brought the relation between the native Sindhis and Muhajirs to such an impasse which resulted in the growth of conspiracy theories, division among Sindhis; subsequently to the demand of Muhajir Suba (Province); target killings, extortion; and eventually to military clean-up operation in Karachi. The paper also throws light on the twin simmering problems of native Sindhis and Muhajirs. Besides, the paper attempts to answer the question as to why the immigrants could not merge in the native Sindhis despite living together for so long and why the native Sindhis remained backward and deprived. Finally, the paper aims at bringing to limelight the role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). -

The Land of Five Rivers and Sindh by David Ross

THE LAND OFOFOF THE FIVE RIVERS AND SINDH. BY DAVID ROSS, C.I.E., F.R.G.S. London 1883 Reproduced by: Sani Hussain Panhwar The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE MOST HONORABLE GEORGE FREDERICK SAMUEL MARQUIS OF RIPON, K.G., P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E., VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, THESE SKETCHES OF THE PUNJAB AND SINDH ARE With His Excellency’s Most Gracious Permission DEDICATED. The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. My object in publishing these “Sketches” is to furnish travelers passing through Sindh and the Punjab with a short historical and descriptive account of the country and places of interest between Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Peshawar, and Delhi. I mainly confine my remarks to the more prominent cities and towns adjoining the railway system. Objects of antiquarian interest and the principal arts and manufactures in the different localities are briefly noticed. I have alluded to the independent adjoining States, and I have added outlines of the routes to Kashmir, the various hill sanitaria, and of the marches which may be made in the interior of the Western Himalayas. In order to give a distinct and definite idea as to the situation of the different localities mentioned, their position with reference to the various railway stations is given as far as possible. The names of the railway stations and principal places described head each article or paragraph, and in the margin are shown the minor places or objects of interest in the vicinity. -

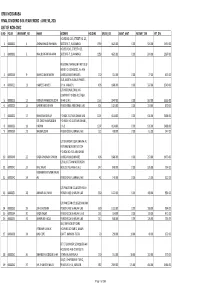

List of Non-CNIC Certificate Holders Final Dividend 2016 31102016.Xlsx

ORIX MODARABA FINAL DIVIDEND 34% YEAR ENDED : JUNE 30, 2016 LIST OF NON-CNIC S.NO FOLIO WARRANT_NO NAME ADDRESS HOLDING GROSS_DIV ZAKAT_AMT INCOME_TAX NET_DIV HOUSE NO. 243, STREET NO. 23, 1 0000002 1 AYSHA KHALID RAHMAN SECTOR E-7, ISLAMABAD. 1359 4621.00 0.00 924.00 3697.00 HOUSE # 243, STREET # 23, 2 0000003 2 KHALID IRFAN RAHMAN SECTOR E-7, ISLAMABAD. 1359 4621.00 0.00 924.00 3697.00 REGIONAL MANAGER FIRST GULF BANK P.O. BOX 18781, AL-AIN 3 0000016 9 SHAHID AMIN SHEIKH UNITED ARAB EMIRATES. 150 510.00 0.00 77.00 433.00 15-B, NORTH AVENUE PHASE I, 4 0000021 11 HAMEED AHMED D.H.A. KARACHI. 496 1686.00 0.00 337.00 1349.00 C/O NATIONAL DRILLING COMPANY P O BOX 4017 ABU 5 0000023 12 MOHSIN HAMEEDDUDDIN DHABI U.A.E. 1161 3947.00 0.00 592.00 3355.00 6 0000025 13 BABER SAEED KHAN PO BOX 3865 ABU DHABI UAE 301 1023.00 0.00 153.00 870.00 7 0000032 17 SHAKEELA BEGUM P.O BOX 2157 ABU DHABI UAE 1207 4104.00 0.00 616.00 3488.00 DR. SYED SHAMSUDDIN P.O. BOX. NO.2157 ABU DHABI., 8 0000033 18 HASHMI U.A.E. 1207 4104.00 0.00 616.00 3488.00 9 0000039 21 NAEEMUDDIN PO BOX 293 FUJAIRAH U.A.E. 120 408.00 0.00 61.00 347.00 C/O SIKANDER IQBAL SHAIKH AL FUTTAIM MOTORS TOYOTA P.O.BOX NO. 555 ABU DHABI 10 0000040 22 RAZIA SHABNAM SHAIKH UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 496 1686.00 0.00 253.00 1433.00 C/O AL FUTTAIM MOTORS PO 11 0000041 23 RIAZ JAVAID BOX 293 FUJAIRAH U.A.E.