Title Page-Option-0.FH10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronologica Dictionary of Sind Chronologial Dictionary of Sind

CHRONOLOGICA DICTIONARY OF SIND CHRONOLOGIAL DICTIONARY OF SIND (From Geological Times to 1539 A.D.) By M. H. Panhwar Institute of Sindhology University of Sind, Jamshoro Sind-Pakistan All rights reserved. Copyright (c) M. H. Panhwar 1983. Institute of Sindhology Publication No. 99 > First printed — 1983 No. of Copies 2000 40 0-0 Price ^Pt&AW&Q Published By Institute of Sindhlogy, University of Sind Jamshoro, in collabortion with Academy of letters Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Education Islamabad. Printed at Educational Press Dr. Ziauddin Ahmad Road, Karachi. • PUBLISHER'S NOTE Institute of Sindhology is engaged in publishing informative material on - Sind under its scheme of "Documentation, Information and Source material on Sind". The present work is part of this scheme, and is being presented for benefit of all those interested in Sindhological Studies. The Institute has already pulished the following informative material on Sind, which has received due recognition in literary circles. 1. Catalogue of religious literature. 2. Catalogue of Sindhi Magazines and Journals. 3. Directory of Sindhi writers 1943-1973. 4. Source material on Sind. 5. Linguist geography of Sind. 6. Historical geography of Sind. The "Chronological Dictionary of Sind" containing 531 pages, 46 maps 14 charts and 130 figures is one of such publications. The text is arranged year by year, giving incidents, sources and analytical discussions. An elaborate bibliography and index: increases the usefulness of the book. The maps and photographs give pictographic history of Sind and have their own place. Sindhology has also published a number of articles of Mr. M.H. Panhwar, referred in the introduction in the journal Sindhology, to make available to the reader all new information collected, while the book was in press. -

List of Non-CNIC Certificate Holders Final Dividend 2016 31102016.Xlsx

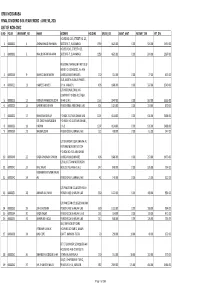

ORIX MODARABA FINAL DIVIDEND 34% YEAR ENDED : JUNE 30, 2016 LIST OF NON-CNIC S.NO FOLIO WARRANT_NO NAME ADDRESS HOLDING GROSS_DIV ZAKAT_AMT INCOME_TAX NET_DIV HOUSE NO. 243, STREET NO. 23, 1 0000002 1 AYSHA KHALID RAHMAN SECTOR E-7, ISLAMABAD. 1359 4621.00 0.00 924.00 3697.00 HOUSE # 243, STREET # 23, 2 0000003 2 KHALID IRFAN RAHMAN SECTOR E-7, ISLAMABAD. 1359 4621.00 0.00 924.00 3697.00 REGIONAL MANAGER FIRST GULF BANK P.O. BOX 18781, AL-AIN 3 0000016 9 SHAHID AMIN SHEIKH UNITED ARAB EMIRATES. 150 510.00 0.00 77.00 433.00 15-B, NORTH AVENUE PHASE I, 4 0000021 11 HAMEED AHMED D.H.A. KARACHI. 496 1686.00 0.00 337.00 1349.00 C/O NATIONAL DRILLING COMPANY P O BOX 4017 ABU 5 0000023 12 MOHSIN HAMEEDDUDDIN DHABI U.A.E. 1161 3947.00 0.00 592.00 3355.00 6 0000025 13 BABER SAEED KHAN PO BOX 3865 ABU DHABI UAE 301 1023.00 0.00 153.00 870.00 7 0000032 17 SHAKEELA BEGUM P.O BOX 2157 ABU DHABI UAE 1207 4104.00 0.00 616.00 3488.00 DR. SYED SHAMSUDDIN P.O. BOX. NO.2157 ABU DHABI., 8 0000033 18 HASHMI U.A.E. 1207 4104.00 0.00 616.00 3488.00 9 0000039 21 NAEEMUDDIN PO BOX 293 FUJAIRAH U.A.E. 120 408.00 0.00 61.00 347.00 C/O SIKANDER IQBAL SHAIKH AL FUTTAIM MOTORS TOYOTA P.O.BOX NO. 555 ABU DHABI 10 0000040 22 RAZIA SHABNAM SHAIKH UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 496 1686.00 0.00 253.00 1433.00 C/O AL FUTTAIM MOTORS PO 11 0000041 23 RIAZ JAVAID BOX 293 FUJAIRAH U.A.E. -

Balkanisation and Political Economy of Pakistan by Yousuf Nazar

BALKANISATION AND POLITICAL ECONOMY OF PAKISTAN YOUSUF NAZAR FOREWORD DR MUBASHIR HASAN @ Copyrights reserved with the author First published in 2008 Revised edition 2011 Published by National News Agency 164 A.M Asad Chamber, Ground Floor, Near Passport Office, Saddar, Karachi, Pakistan. Tel: 021-3568828, 35681520 Fax: 021-35682391 web: www.nnagency.com Email: [email protected] Official Correspondence 4-C, 14th Commercial Street, D.H.A., Phase II Ext., Karachi, Pakistan. Tel: 021-35805391-3 Email: [email protected] Produced and design by Mirador Printed by Elliya Printers This book is dedicated to those 60%-70% Pakistanis who live in poverty and survive on less than 2 Dollars a day About the author Yousuf Nazar is an international finance professional with specialisation in emerging economies. As the head of Citigroup’s emerging markets public equity investments unit based in London from 2001 to 2005, he helped Citigroup manage its over US $2 billion proprietary equity portfolio in the emerging markets of Asia, Latin America, Central/Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa. Before this assignment, he also served as a Director of Citibank’s strategic planning group during the 1990s. Since 2006, he has written many articles on Pakistan’s political and economic issues with a particular focus on the developments in an international context. His interest in politics dates back to his student days as a political activist when he worked against General Zia-ul Haq’s martial law in 1977. His experience in the developing countries spanned across several areas of international finance. He did his Bachelor's degree in administrative studies and an MBA in international finance and economics from York University in Toronto. -

Kurrachee (Karachi) Past: Present and Future

KURRACHEE (KARACHI) PAST: PRESENT AND FUTURE ALEXANDER F. BAILLIE, F.R.G.S., 1880 BIRD'S EYE VIEW OF VICTORIA ROAD CLERK STREET, SADDAR BAZAR KARACHI REPRODUCED BY SANI H. PANHWAR (2019) KUR R A CH EE: PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. KUR R A CH EE: (KA R A CH I) PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. BY A LEXA NDER F.B A ILLIE,F.R.G.S., A uthor of"A PA RA GUA YA N TREA SURE,"etc. W ith M a ps,Pla ns & Photogra phs 1890. Reproduced by Sa niH .Panhw a r (2019) TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE GRANT-DUFF, P.C., G.C.S.I., C.I.E., F.R.S., M.R.A.S., PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, FORMERLY UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA, AND GOVERNOR OF THE PROVINCE OF MADRAS, ETC., ETC., THIS ACCOUNT OF KURRACHEE: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE, IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. INTRODUCTION. THE main objects that I have had in view in publishing a Treatise on Kurrachee are, in the first place, to submit to the Public a succinct collection of facts relating to that City and Port which, at a future period, it might be difficult to retrieve from the records of the Past ; and secondly, to advocate the construction of a Railway system connecting the GateofCentralAsiaand the Valley of the Indus, with the Native Capital of India. I have elsewhere mentioned the authorities to whom I am indebted, and have gratefully acknowledged the valuable assistance that, from numerous sources, has been afforded to me in the compilation of this Work; but an apology is due to my Readers for the comments and discursions that have been interpolated, and which I find, on revisal, occupy a considerable number of the following pages. -

Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Informal Land Controls, A Case of Karachi-Pakistan. This Thesis is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Saeed Ud Din Ahmed School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University June 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i | P a g e STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………………………………………..………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………………………………………….…………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………………………………………………….……………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii | P a g e iii | P a g e Acknowledgement The fruition of this thesis, theoretically a solitary contribution, is indebted to many individuals and institutions for their kind contributions, guidance and support. NED University of Engineering and Technology, my alma mater and employer, for financing this study. -

Political Turmoil in a Megacity: the Role of Karachi for the Stability of Pakistan and South Asia

Political Turmoil in a Megacity: The Role of Karachi for the Stability of Pakistan and South Asia Bettina Robotka Political parties are a major part of representative democracy which is the main political system worldwide today. In a society where direct modes of democracy are not manageable any more – and that is the majority of modern democracies- political parties are a means of uniting and organizing people who share certain ideas about how society should progress. In South Asia where democracy as a political system was introduced from outside during colonial rule only few political ideologies have developed. Instead, we find political parties here are mostly based on ethnicity. The flowing article will analyze the Muttahida Qaumi Movement and the role it plays in Karachi. Karachi is the largest city, the main seaport and the economic centre of Pakistan, as well as the capital of the province of Sindh. It is situated in the South of Pakistan on the shore of the Arabian Sea and holds the two main sea ports of Pakistan Port Karachi and Port Bin Qasim. This makes it the commercial hub of and gateway to Pakistan. The city handles 95% of Pakistan’s foreign trade, contributes 30% to Pakistan’s manufacturing sector, and almost 90% of the head offices of the banks, financial institutions and 2 Pakistan Vision Vol. 14 No.2 multinational companies operate from Karachi. The country’s largest stock exchange is Karachi-based, making it the financial and commercial center of the country as well. Karachi contributes 20% of the national GDP, adds 45% of the national value added, retains 40% of the national employment in large-scale manufacturing, holds 50% of bank deposits and contributes 25% of national revenues and 40% of provincial revenues.1 Its population which is estimated between 18 and 21million people makes it a major resource for the educated and uneducated labor market in the country. -

Art Deco: the Lost Glory of Karachi

Art Deco: The Lost Glory of Karachi Written and Researched by: Marvi Mazhar, Anushka Maqbool, Harmain Ahmer Research Team: Harmain Ahmer, Hareem Naseer, Marvi Mazhar, Anushka Maqbool Contents 0 Prologue 1 Introduction 2 Progression of Karachi’s Architecture 3 The Art Deco Movement: Global to Local 4 Influences on Architecture: Symbols and Furniture 5 A South Asian Network: Art Deco Insta Family 6 Conclusion: Karachi’s Urban Decay and Way Forward ©MMA 0 Prologue Owners currently residing in the historical bungalows are interviewed. ‘For many developing nations, modernity is associated with pro- The history of the bungalow and its evolution through the owners and gress and there is an aspiration towards western styles of living; the secondary research would be found. The methodology and approach old is rejected for being backward, and historic continuity becomes that is used to document the historical buildings is extremely impor- disregarded in favor of the status of the modern.’ tant for the preservation and protection process under Heritage Law. This type of research and documentation methodology is holistic and Historic Bungalow Research is an ongoing documentation project of investigative, unlike the current governmental approach to heritage the historic buildings of Sindh. It is conducted by performing extensive documentation, which is carried out on a superficial level. field work and collecting oral narratives and literature. The work -in The research aims to document, understand, and profile century old volves analysing bungalow typologies, spatial definition, material tech- bungalows across Sindh for archival purposes. Educating current and niques, craftsmanship and personally owned artifacts which define -ma future generations about the existence and beauty of these historical terial memory. -

The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics

MONOGRAPHS IN THE ECONOMICS OF DEVELOPMENT No. 13 The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics SULTAN S. HASHMI January 1965 PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS Old Sind Assembly Building Bunder Road, Karachi (Pakistan) Price Rs. 5.00 PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPME :ONOMICS Old Sind Assembly Building Bunder Road, Karachi-1 (Pakistan) The Institute carries out basic research studies on the economic problems of development in Pakistan and other Asian countries. It also provides training in economic analysis and research methodology for the professional members of its staff and for members of other organization concerned with development problems. Executive Board Mr. Said Hasan, H.Q.A. (Chairman) Mr. S. A. F. M. A. Sobhan Mr. G. S. Kehar, S.Q.A. (Member) (Member) Mr. M. L. Qureshi, S.Q.A. Mr. M. Raschid (Member) (Member) Mr. A. Rashid Ibrahim Mr. S. M. Sulaiman (Member-Treasurer) (Member) Professor A. F. A. Hussain Dr. Mahbubul Haq (Member) (Member) Mian Nazir Ahmad, T.Q.A. (Secretary) Director: Professor Nurul Islam Senior Research Adviser: Dr. Bruce Glassburner Research Advisers: Dr. W. Eric Gustafson; Dr. Ronald Soligo; Dr. Stephen R. Lewis, Jr.; Dr. Warren C. Robinson; Mr. William Seltzer. Senior Fellows: Dr. S. A. Abbas; Dr. M. Baqai; Dr. Mahbubul Haq; Professor T. Haq; Professor A. F. A. Hussain; Dr. R. H. Khandkar; Dr. Taufique Khan; Professor M. Rashid. Advisory Board Professor Max F. Millikan, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Professor Gunnar Myrdal, University of Stockholm. Professor E. A. G. Robinson, Cambridge University. MONOGRAPHS IN THE ECONOMICS OF DEVELOPMENT No. 13 The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics SULTANS. -

Understanding Karachi: Patterns of Conflict and Their Implications

Pakistan Perspectives Vol. 22, No.2, July-December 2017 Focus on Karachi Understanding Karachi: Patterns of Conflict and their Implications Naeem Ahmed* Abstract The paper critically examines the patterns of conflict in Karachi and their socio- economic, political and security implications by arguing that many of the conflicts flourish under the political umbrellas, and the city has become the victim to the power temptations and control on part of political actors. In order to understand the patterns of conflict in today‘s Karachi, there are four different, but inter-related and in some cases overlapping, aspects – ethno-political; sectarian; terrorism; and crime-related conflicts – which not only have made the situation more complex, but also led to a perpetual wave of violence in the city. The paper further argues that many of Karachi‘s conflicts have emanated from two inter-connected processes: unchecked influx of migrants in various phases, and as a result the formation of informal squatter settlements. In order to resolve Karachi‘s conflicts, the paper, therefore, suggests both short-term and long-term strategies, which focus on the issues of governance which would help separate the nexus between politics, criminality and militancy; and the need for changing Pakistan‘s security narrative vis-à-vis its eastern and western neighbors respectively. ______ Introduction On 11 June 2015, the Director General of Sindh Rangers, Major General Bilal Akbar, during the Sindh Apex Committee meeting revealed a link between criminality, politics and violence in Karachi. According to the press release, General Akbar said that an evil nexus of political leaders, civil servants and gang lords was involved in nurturing and sheltering organized crime and terrorism in Karachi. -

Studies on Karachi

Studies on Karachi Studies on Karachi Papers Presented at the Karachi Conference 2013 Edited by Sabiah Askari Studies on Karachi: Papers Presented at the Karachi Conference 2013 Edited by Sabiah Askari This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Sabiah Askari and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7744-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7744-2 CONTENTS Introduction to the Karachi Conference Foundation ................................ viii Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Rumana Husain Keynote Address at The Karachi Conference 2013 ..................................... 1 Arif Hasan Part I: History and Identity Prehistoric Karachi .................................................................................... 16 Asma Ibrahim Cup-Marks at Gadap, Karachi ................................................................... 35 Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro Shaping a New Karachi with the Merchants: Mercantile Communities and the Dynamics of Colonial Urbanization (1851-1921) ......................... 58 Michel Boivin -

12086369 01.Pdf

Exchange Rate 1 Pakistan Rupee (Rs.) = 0.871 Japanese Yen (Yen) 1 Yen = 1.148 Rs. 1 US dollar (US$) = 77.82 Yen 1 US$ = 89.34 Rs. Table of Contents Executive Summary Introduction Chapter 1 Review of Policies, Development Plans, and Studies .................................................... 1-1 1.1 Review of Urban Development Policies, Plans, Related Laws and Regulations .............. 1-1 1.1.1 Previous Development Master Plans ................................................................................. 1-1 1.1.2 Karachi Strategic Development Plan 2020 ........................................................................ 1-3 1.1.3 Urban Development Projects ............................................................................................. 1-6 1.1.4 Laws and Regulations on Urban Development ................................................................. 1-7 1.1.5 Laws and Regulations on Environmental Considerations ................................................. 1-8 1.2 Review of Policies and Development Programs in Transport Sector .............................. 1-20 1.2.1 History of Transport Master Plan .................................................................................... 1-20 1.2.2 Karachi Mass Transit Corridors ...................................................................................... 1-22 1.2.3 Policies in Transport Sector ............................................................................................. 1-28 1.2.4 Karachi Mega City Sustainable Development Project (ADB) -

Karachi, Pakistan by Arif Hasan Masooma Mohib Source: CIA Factbook

The case of Karachi, Pakistan by Arif Hasan Masooma Mohib Source: CIA factbook Contact Arif Hasan, Architect and Planning Consultant, 37-D, Mohd. Ali Society, Karachi – 75350 Tel/Fax. +92.21 452 2361 E-mail: [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION: THE CITY A. URBAN CONTEXT 1. National Overview Table A1.1 below gives an overview of demographic 1951 – 1961: During this period, there was a sharp and urbanisation trends in Pakistan. The urban popula- fall in infant mortality rates. This was because of the tion has increased from 4,015,000 (14.2 per cent of the eradication of malaria, smallpox and cholera through the total) in 1941 to 42,458,000 (32.5 per cent of total) in use of pesticides, immunisation and drugs. Urban popu- 1998. The 1998 figures have been challenged since lations started to increase due to the push factor created only those settlements have been considered as urban by the introduction of Green Revolution technologies in which have urban local government structures. agricultural production. Population density as a whole has also increased from 42.5 people per km2 in 1951 to 164 in 1998. 1961 – 1972: An increase in urbanisation and overall Major increases in the urban population occurred demographic growth continued due to the trends during the following periods: explained above. In addition, Pakistan started to indus- trialise during this decade. This created a pull factor 1941 – 1951: This increase was due to the migration which increased rural-urban migration. These trends from India in 1947 when the subcontinent was parti- continued during the next decade.