Understanding Karachi: Patterns of Conflict and Their Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIVIL TRANSPORTERS - BAHRIA COLLEGE KARSAZ Transport Incharge : Javed Amjad Kayani: 0343-2432072 - 0302-5723178

CIVIL TRANSPORTERS - BAHRIA COLLEGE KARSAZ Transport Incharge : Javed Amjad Kayani: 0343-2432072 - 0302-5723178 S# Name Contact # Vehicle Route Morning & Evening 1 Abdul Salam 3002185124 Hiace Saddar, Garden, Jamshed Road 2 Abid Sheikh 3002454876 Hiroof University, Gulistan-e-Johar, Kiran Hospital 3 Amin Ud Din 3002519301 Hiace PIB Colony, Jamshed Raod, Chandni Chok, Bahadurabad 4 Shahbaz 3139030400 Hiroof Dalmian NHS Phase I & II 5 Asif 3432468290 Hiroof Shah Faisal, Rafay e Ama, Jumma Goth, Green Town 6 Atta Ullah 3332224684 Hiroof Majeed SRE, Dalmia 7 Bilal 3320337639 Hiace Manzor Colony DHA Phase II Qayumabad 8 Faisal Abbas 3462593009 Mazda Nagan Chorangi, Disco Bakery, Maskan 9 Farhat Abbas 3002327290 Coaster Gulshan-e-Jamal, Gulistan-e-Jouhar, Rabia City 10 Fiaz 3101288299 Hiace Azizabad, Karimabad, Gol Market 11 Haseeb 3162594642 Hiace 4K, Bufferzone, Shafi Mor, Sohrab Goth 12 Imran 3338999790 Hiroof Baloch Colony, Manzoor Colony 13 Imran Burfat 3213380750 Hiroof Dalmia 14 Islam ud Din 3332294481 Coaster Gulistan-e-Johar 15 Jamil ud Din 3003645880 Coaster Shah Faisal Colony 16 Jaseem Ahmed Khan 3002484125 Hiroof saudi Town, Safora, Malir Cantt, Karachi Universty falcon 17 K M Yaqoob 3002170136 Mazda Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Mochi Mor, Expo Centre 18 Kaleem 3462695707 Coaster Essa Nagri, Azizabad, Tahir Villa, 4K Chorangi 19 Khan Baba 3332294959 Hiace Bhadurabad, Sharfabad, Guru Mander, Soldier Bazar 20 M Aqil 3161605887 Hi-Roof Shah Faisal 1 , 2 , 3 and 5 Golden Town 21 M Yamin 3012721186 Hiace Nursery, NORE-I, Lucky Star 22 M. Akbar 3002157893 Hiroof Clifton,Seaview,Teen Talwar,NORE II Sharahefaisal 23 M. Farooq Patel 3073516561 Hiace Landhi, Quaidabad 24 M. -

Will Terrorism Hijack the Pakistani Elections? Kiran Hassan*

Opinion: Will Terrorism Hijack the Pakistani Elections? Kiran Hassan* Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, UK *[email protected] First published in the Daily Times of Pakistan, 22 April 2013.1 Pakistan expects a historic general election in 2013 which might be jeopardized by terrorist attacks. For the first time, a momentous democratic transition – in which one democratically elected government, after completing its full term, will succeed another – is about to take place. Yet many suspect that if the fresh bout of violence from militant groups continues, furthering chaos and lawlessness, the expected general election might not happen. Militancy continues to be the hydra-headed beast that the top Pakistani leadership has failed to slay. The critical question remains: Is the Pakistani leadership willing to tackle this breeding problem or is it comfortable with remaining habitually complacent? The New Year brought shameful and dreaded assaults by extremist groups on the Pakistani Shia community. Groups such as Lashkar-e-Jhangvi have long regarded Shia Muslims as heretics. Stepping up attacks recently, the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (a banned organization) are thought to have set up several training camps for militants, and have access to large quantities of weapons and explosives. The brutality started when 81 people were killed and 121 injured in a suicide car bomb blasts in Quetta’s Alamdar Road area on the night of then 10th of January 2013.2 Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed responsibility for the attack. The majority of the people killed in the Alamdar Road blasts belonged to the Hazara Shia community. -

12086393 01.Pdf

Exchange Rate 1 Pakistan Rupee (Rs.) = 0.871 Japanese Yen (Yen) 1 Yen = 1.148 Rs. 1 US dollar (US$) = 77.82 Yen 1 US$ = 89.34 Rs. Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Karachi Transportation Improvement Project ................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1 Background................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1.2 Work Items ................................................................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.3 Work Schedule ........................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.2 Progress of the Household Interview Survey (HIS) .......................................................................... 1-5 1.3 Seminar & Workshop ........................................................................................................................ 1-5 1.4 Supplementary Survey ....................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.4.1 Topographic and Utility Survey................................................................................................. 1-6 1.4.2 Water Quality Survey ............................................................................................................... -

Subject: Details of Vehicles and Routes Plying for MAJU As Third Party

March 17, 2021 Muhammad Ali Jinnah University, Block – 6, PECHS, Shahrah-E- Faisal, Karachi. Subject: Details of Vehicles and Routes Plying for MAJU as Third Party Rout Driver Cell Registration Total Capacity Driver Name Vehicle Type Rout Code No. No. Capacity Utilized MAJU 1 Kumail Hussain 03162458082 CU-9807 Hijet 7 7 Model Colony - Tariq Bin Ziyad – Malir Halt MAJU 2 Kashif Hussain 03142994018 CD-5224 Hiroof Bolan 7 7 Khokrapar - Malir Cantt. – Shahrah-E-Faisal MAJU 3 Raheel Ahmed 03096551061 CR-9530 Hiroof Bolan 7 7 Malir City – Shah Faisal – Drig Road MAJU 4 Raja Khan 03142254080 CV-2294 Suzuki Every 7 6 Landhi 1 & 6 - Korangi 1 & 2 ½ - Crossing MAJU 5 Faisal Khan 03162111826 CN-9870 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Korangi 5 & 5 1/2 – Qayyumabad – Kala Pul MAJU 6 Yahya 03101043920 CG-7681 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Saadi Town - Mosmiat - New Rizviya – Johar 1 MAJU 7 M. Ibrahim 03011109270 JF-7063 Hilex 15 14 Safora - Samama - Continental – Gul. Johar MAJU 8 Imran 03340298838 CU-6365 Hiroof Bolan 7 5 Maymaar - Scheme 33 - Abul Asfahani Road MAJU 9 Sunny 03322399422 CS-6522 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Abul Afahani - Nipa - Hasan Square – Stadium MAJU 10 M. Shariq 03222112478 CG-7001 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Sarjani - North Karachi - North Nazimabad MAJU 11 M. Zakir 03118481919 CP-9062 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 New Nazimabad - Anda Mod - North Nazimabd MAJU 12 Fahim 03337143644 CP-8171 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Nagan - Bafarzone - Sohrab Goth – Rashid Min. MAJU 13 Nasir 03008967707 CN-2540 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Bada Board - Nazimabad – Paposh – Lasbila MAJU 14 Shehroz 03172175553 CK-8868 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Board office - Golimar - Lalo Kheth – New town MAJU 15 Moiz 03113246303 CY-2289 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Five Star - Sakhi Hasan – FB Area – Azizabad MAJU 16 Ali 03342575308 CN-4047 Hiroof Bolan 7 6 Gulberg - Waterpump - Mukka Chok – 13D MAJU 17 Aashiq 03022480771 CU-0496 Hiroof Bolan 7 7 FB Area - Ancholi - Alnoor - Sohrab Goth MAJU 18 M. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for Construction and Rehabilitation of National Highway N-5 in Karachi City in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan Karachi Metropolitan Corporation PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION AND REHABILITATION OF NATIONAL HIGHWAY N-5 IN KARACHI CITY IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN JANUARY 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY INGÉROSEC CORPORATION EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. EI JR 17-0 PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the preparatory survey and entrust the survey to the consortium of INGÉROSEC Corporation and Eight-Japan Engineering Consultants Inc. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, and conducted field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan and the explanation of survey result in Pakistan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. January, 2017 Akira Nakamura Director General, Infrastructure and Peacebuilding Department Japan International Cooperation Agency SUMMARY SUMMARY (1) Outline of the Country The Islamic Republic of Pakistan (hereinafter referred to as Pakistan) is a large country in the South Asia having land of 796 thousand km2 that is almost double of Japan and 177 million populations that is 6th in the world. In 2050, the population in Pakistan is expected to exceed Brazil and Indonesia and to be 335 million which is 4th in the world. -

East-Karachi

East-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 East Karachi Jamshed Town 1-Akhtar Colony 408070173 GBLSS - H.M.A. Middle Mixed 7,841 1,568 4,705 3,137 1,568 6,273 25,093 6,273 31,366 2 East Karachi Jamshed Town 2-Manzoor Colony 408070139 GBPS - BILAL MASJID NO.2 Primary Mixed 12,559 2,512 10,047 2,512 2,512 10,047 40,189 10,047 50,236 3 East Karachi Jamshed Town 2-Manzoor Colony 408070174 GBLSS - UNION Middle Mixed 16,613 3,323 13,290 3,323 3,323 13,290 53,161 13,290 66,451 4 East Karachi Jamshed Town 9-Central Jacob Line 408070171 GBLSS - BATOOL GOVT` BOYS`L/SEC SCHOOL Middle Mixed 12,646 2,529 10,117 2,529 2,529 10,117 40,466 10,117 50,583 5 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070160 GBLSS - AZMAT-I-ISLAM Middle Boys 22,422 4,484 17,937 4,484 4,484 17,937 71,749 17,937 89,687 6 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070162 GBLSS - RANA ACADEMY Middle Boys 13,431 2,686 8,059 5,372 2,686 10,745 42,980 10,745 53,724 7 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070163 GBLSS - MAHMOODABAD Middle Boys 20,574 4,115 12,344 8,230 4,115 16,459 65,836 16,459 82,295 8 East Karachi Jamshed Town 11-Garden East 408070172 GBLSS - GULSHAN E FATIMA Middle Mixed 16,665 3,333 13,332 3,333 3,333 13,332 53,327 13,332 66,658 9 East Karachi Gulshan-e-Iqbal Town 3-PIB -

Shuttle Route

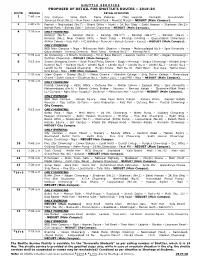

SHUTTLE SERVICES PROPOSED OF DETAIL FOR SHUTTLE’S ROUTES – 2019-20 ROUTE TIMINGS DETAIL OF ROUTES 1 7:40 a.m City Campus – Jama Cloth – Radio Pakistan – 7Day Hospital – Numaish – Gurumandir – Jamshed Road (No.3) – New Town – Askari Park – Mumtaz Manzil – NEDUET (Main Campus). 2 7:40 a.m Paposh – Nazimabad (No.7) – Board Office – Hydri – 2K Bus Stop – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman (No.2)– Namak Bank – Sohrab Goth – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 4 7:20 a.m ONLY MORNING: Korangi (No.5) – Korangi (No.4) – Korangi (No.31/2) – Korangi (No.21/2) – Korangi (No.2) – Korangi (No.1, Near Chakra Goth) – Nasir Jump – Korangi Crossing – Qayyumabad Chowrangi – Akhtar Colony – Kala Pull – FTC Building – Nursery – Baloch Colony – Karsaz – NEDUET (Main Campus). ONLY EVENING: NED Main Campus – Nipa – Millennium Mall– Stadium – Karsaz – Mehmoodabad No.6 – Iqra University – Qayyumabad – Korangi Crossing – Nasir Jump – Korangi No.21/2 – Korangi No.5. 5 7:45 a.m 4K Chowrangi – 2 Minute Chowrangi – 5C-4 (Bara Market) – Saleem Centre – U.P Mor – Nagan Chowrangi – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 6 7:15 a.m Shama Shopping Centre – Shah Faisal Police Station – Bagh-e-Korangi – Singer Chowrangi – Khaddi Stop – Korangi No.5 – Korangi No.6 – Landhi No.6 – Landhi No.5 – Landhi No.4 – Landhi No.3 – Landhi No.1 – Landhi No.89 – Dawood Chowrangi – Murghi Khana – Malir No.15 – Malir Hault – Star Gate – Natha Khan – Drig Road – Nipa – NED Main Campus. 7 7:35 a.m Islam Chowk – Orangi (No.5) – Metro Cinema – Abdullah College – Ship Owner College – Qalandarya Chowk – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman No.1 – Buffer Zone – Fazal Mill – Nipa – NEDUET (Main Campus). -

List of Settlements Evicted 1997

List of displaced settlements 1997 – 2005 Urban Resource Centre A-2/2, 2nd Floor, Westland Trade Centre, Commercial Area, Shaheed-e-Millat Road, Karachi Co-operative Housing Society Union, Block 7 & 8 Karachi Pakistan Tel: +92 21 - 4559317 Fax: 4387692 Web site : www.urckarachi.org E-mail: [email protected] XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX I Appendix – : List 1 Details of the some recent Evictions cases Settlement /area Date No. Reasons Houses bulldozed Noor Muhammad Village Karsaz 29/05/97 400 KWSB wanted to build its office building Junejo Town Manzoor Colony 05/10/97 150 KDA land Garam Chashma Goth Manghopir 22/11/97 150 Land grabbers were involved. Umer Farooq Town Kalapul 23/02/98 100 Bridge extension Manzoor Colony 21/05/98 20 Liaquat Colony Lyari 17/10/98 190 KMC declared a 100 years old settlement as an amenity plot. Glass Tower Clifton 26/11/98 10 Parking for Glass Tower Ghareebabad, Sabzi Mandi and Quaid 28/12/98 250 Access road for law & order e Azam Colony agencies Buffer Zone 10/02/99 35 Land dispute Kausar Niazi colony North Nazimabad 17/02/99 30 Land dispute Zakri Baloch Goth Gulistan-e-Jauhar 15/03/99 250 Builders wanted the land for high rise construction Al Hilal Society Sabzi Mandi 15/03/99 62 Builders involved Sikanderabad Clony KPT 23/08/99 40 KPT reclaimed its land Gudera Camp New Karachi 17/11/99 350 Operation against encroachments Sher Pao Colony M.A. Society 29/11/99 60 Amenity plot Gilani railway station 20/01/00 160 Railway land Grumandir 02/08/00 37 shops Road extension by the KMC Chakara Goth Nasir Colony -

Crisis Response Bulletin V3I1.Pdf

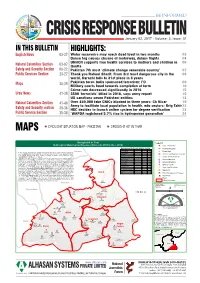

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN January 02, 2017 - Volume: 3, Issue: 01 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 03-27 Water reservoirs may reach dead level in two months 03 Dense fog causes closure of motorway, delays flights 04 UNHCR supports free health services to mothers and children in 06 Natural Calamities Section 03-07 Quetta Safety and Security Section 08-22 Pakistan 7th most ‘climate change venerable country’ 07 Public Services Section 23-27 Thank you Raheel Sharif: From 3rd most dangerous city in the 08 world, Karachi falls to 31st place in 3 years Maps 28-29 Pakistan faces India sponsored terrorism: FO 09 Military courts head towards completion of term 10 Crime rate decreased significantly in 2016 15 Urdu News 41-30 3500 ‘terrorists’ killed in 2016, says army report 15 US sanctions seven Pakistani entities 18 Natural Calamities Section 41-40 Over 450,000 fake CNICs blocked in three years: Ch Nisar 19 Army to facilitate local population in health, edu sectors: Brig Tahir23 Safety and Security section 39-36 HEC decides to launch online system for degree verification 23 Public Service Section 35-30 ‘WAPDA registered 5.7% rise in hydropower generation’ 24 MAPS DROUGHT SITUATION MAP - PAKISTAN DROUGHT HIT IN THAR Drought Hit in Thar Legend Outbreak of Waterborne Diseases (from Jan,2016 to Dec, 2016) G Basic Health Unit Government & Private Health Facility ÷Ó Children Hospital Health Facility Government Private Total Sanghar Basic Health Unit 21 0 21 G Dispensary At least nine more infants died due to malnutrition and outbreak of the various diseases in Thar during that last two Children Hospital 0 1 1 days, raising the toll to 476 this year.With the death of nine more children the toll rose to 476 during past 12 months Dispensary 12 0 12 "' District Headquarter Hospital of the outgoing year, said health officials. -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Rawalpindi Cantonment Board

1 RAWALPINDI CANTONMENT BOARD Tele: 051-9274401-04 Facsimile No. 051-9274407 PROCEEDINGS OF THE ORDINARY MEETING OF RAWALPINDI CANTONMENT BOARD HELD ON 11THSEPTEMBER, 2020. Present 1. Brig Ijaz Qamar Kiani - President 2. Malik Munir Ahmad - Vice President 3. Malik Sajid Mehmood - Member 4. Malik Muhammad Usman - Member 5. Mr. Muhammad Shafique - Member 6. Mr. Rasheed Ahmad Khan - Member 7. Raja Jahandad Khan - Member 8. Haji Zafar Iqbal - Member 9. Malik Mansoor Afsar - Member 10. Mr. Arshad Mehmood Qureshi - Member 11. Hafiz Hussain Ahmad Malik - Member 12. Mr. Shahid Mughal - Member 13. Mr. Yousuf Gill - Member 14. Lt. Col. Muhammad Mukarram Khan, Sta HQs - Member 15. Lt. Col. Muhammad Asim Raza Khan, Transit Camp- Member SECRETARY Mr. Mohammad Omar Farooq Ali Malik - Secretary / CEO ABSENT 1. Maj. Muhammad Ali Tajik, Sta HQs, Rawalpindi - Member 2. Lt. Col. Maqsood Ashraf, AMC / MH - Member 3. Lt. Col. Muhammad Asif Sultan, AFIC - Member 4. Maj. Ali Hassan Sayed, MH - Member 5. Maj. Muhammad Aamir Mustafa, AFIC - Member 6. Maj. Aleem Zafar, AFIC - Member 7. Lt. Col Rizwan Ghani, AMC–Health Officer - Ex Officio Member 8. Maj. Syed Ishtiaq Ahmad, GE(A) Rwp 1 - Ex Officio Member 9. Syed Zaffar Hassan Naqvi, SJM, RCB - Ex Officio Member ______________________________________________ Before transaction of routine business / agenda, verses from the Holy Quran were recited. ______________________________________________ 2 INDEX ITEM SUBJECT NUMBER 1. MONTHLY ACCOUNT 2. APPROVAL OF BUILDING PLANS ( RESIDENTIAL). 3. APPROVAL OF BUILDING PLANS ( RESIDENTIAL) 4. APPROVAL OF BUILDING PLANS ( RESIDENTIAL) 5. APPROVAL OF BUILDING PLANS ( RESIDENTIAL) 6. APPROVAL OF BUILDING PLANS ( RESIDENTIAL) 7. PROCEEDINGS OF BAZAR COMMITTEE MEETING HELD ON 16-07-2020 8. -

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`I Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!Q

MEI Report Sunni Deobandi-Shi`i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence Since 2007 Arif Ra!q Photo Credit: AP Photo/B.K. Bangash December 2014 ! Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Sectarian Violence in Pakistan Explaining the Resurgence since 2007 Arif Rafiq! DECEMBER 2014 1 ! ! Contents ! ! I. Summary ................................................................................. 3! II. Acronyms ............................................................................... 5! III. The Author ............................................................................ 8! IV. Introduction .......................................................................... 9! V. Historic Roots of Sunni Deobandi-Shi‘i Conflict in Pakistan ...... 10! VI. Sectarian Violence Surges since 2007: How and Why? ............ 32! VII. Current Trends: Sectarianism Growing .................................. 91! VIII. Policy Recommendations .................................................. 105! IX. Bibliography ..................................................................... 110! X. Notes ................................................................................ 114! ! 2 I. Summary • Sectarian violence between Sunni Deobandi and Shi‘i Muslims in Pakistan has resurged since 2007, resulting in approximately 2,300 deaths in Pakistan’s four main provinces from 2007 to 2013 and an estimated 1,500 deaths in the Kurram Agency from 2007 to 2011. • Baluchistan and Karachi are now the two most active zones of violence between Sunni Deobandis and Shi‘a,