Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools JUL 0 2 2003

Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri B.S. Architecture Studies University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2001 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2003 JUL 0 2 2003 Copyright@ 2003 Mahjabeen Quadri. Al rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Mahjabeen Quadri Departm 4t of Architecture, May 19, 2003 Certified by:- Reinhard K. Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Julian Beinart Departme of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students ROTCH Thesis Committee Reinhard Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Edith Ackermann Visiting Professor Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Anna Hardman Visiting Lecturer in International Development Planning Department of Urban Studies and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Hashim Sarkis Professor of Architecture Aga Khan Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism Harvard University Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 23, 2003 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract Pakistan's greatest resource is its children, but only a small percentage of them make it through primary school. -

Will Terrorism Hijack the Pakistani Elections? Kiran Hassan*

Opinion: Will Terrorism Hijack the Pakistani Elections? Kiran Hassan* Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, UK *[email protected] First published in the Daily Times of Pakistan, 22 April 2013.1 Pakistan expects a historic general election in 2013 which might be jeopardized by terrorist attacks. For the first time, a momentous democratic transition – in which one democratically elected government, after completing its full term, will succeed another – is about to take place. Yet many suspect that if the fresh bout of violence from militant groups continues, furthering chaos and lawlessness, the expected general election might not happen. Militancy continues to be the hydra-headed beast that the top Pakistani leadership has failed to slay. The critical question remains: Is the Pakistani leadership willing to tackle this breeding problem or is it comfortable with remaining habitually complacent? The New Year brought shameful and dreaded assaults by extremist groups on the Pakistani Shia community. Groups such as Lashkar-e-Jhangvi have long regarded Shia Muslims as heretics. Stepping up attacks recently, the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (a banned organization) are thought to have set up several training camps for militants, and have access to large quantities of weapons and explosives. The brutality started when 81 people were killed and 121 injured in a suicide car bomb blasts in Quetta’s Alamdar Road area on the night of then 10th of January 2013.2 Lashkar-e-Jhangvi claimed responsibility for the attack. The majority of the people killed in the Alamdar Road blasts belonged to the Hazara Shia community. -

SEF Assisted Schools (SAS)

Sindh Education Foundation, Govt. of Sindh SEF Assisted Schools (SAS) PRIMARY SCHOOLS (659) S. No. School Code Village Union Council Taluka District Operator Contact No. 1 NEWSAS204 Umer Chang 3 Badin Badin SHUMAILA ANJUM MEMON 0333-7349268 2 NEWSAS179 Sharif Abad Thari Matli Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 3 NEWSAS178 Yasir Abad Thari Matli Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 4 NEWSAS205 Haji Ramzan Khokhar UC-I MATLI Matli Badin ZEESHAN ABBASI 0300-3001894 5 NEWSAS177 Khan Wah Rajo Khanani Talhar Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 6 NEWSAS206 Saboo Thebo SAEED PUR Talhar Badin ZEESHAN ABBASI 0300-3001894 7 NEWSAS175 Ahmedani Goth Khalifa Qasim Tando Bago Badin GREEN CRESCENT TRUST (GCT) 0304-2229329 8 NEWSAS176 Shadi Large Khoski Tando Bago Badin GREEN CRESCENT TRUST (GCT) 0304-2229329 9 NEWSAS349 Wapda Colony JOHI Johi Dadu KIFAYAT HUSSAIN JAMALI 0306-8590931 10 NEWSAS350 Mureed Dero Pat Gul Mohammad Johi Dadu Manzoor Ali Laghari 0334-2203478 11 NEWSAS215 Mureed Dero Mastoi Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 12 NEWSAS212 Nabu Birahmani Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION & REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 13 NEWSAS216 Phullu Qambrani Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 14 NEWSAS214 Shah Dan Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 15 RBCS002 MOHAMMAD HASSAN RODNANI -

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

Malir-Karachi

Malir-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Malir Karachi Gadap Town NA 408180381 GBLSS - HUSSAIN BLAOUCH Middle Boys 14,324 2,865 8,594 5,729 2,865 11,459 45,836 11,459 57,295 2 Malir Karachi Gadap Town NA 408180436 GBELS - HAJI IBRAHIM BALOUCH Elementary Mixed 24,559 4,912 19,647 4,912 4,912 19,647 78,588 19,647 98,236 3 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180426 GBELS - HASHIM KHASKHELI Elementary Boys 42,250 8,450 33,800 8,450 8,450 33,800 135,202 33,800 169,002 4 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180434 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.3 OLD Elementary Mixed 35,865 7,173 28,692 7,173 7,173 28,692 114,769 28,692 143,461 5 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 1-Murad Memon Goth (Malir) 408180435 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.3 NEW Elementary Mixed 24,882 4,976 19,906 4,976 4,976 19,906 79,622 19,906 99,528 6 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 2-Darsano Channo 408180073 GBELS - AL-HAJ DUR MUHAMMAD BALOCH Elementary Boys 36,374 7,275 21,824 14,550 7,275 29,099 116,397 29,099 145,496 7 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 2-Darsano Channo 408180428 GBELS - MURAD MEMON NO.1 Elementary Mixed 33,116 6,623 26,493 6,623 6,623 26,493 105,971 26,493 132,464 8 Malir Karachi Gadap Town 3-Gujhro 408180441 GBELS - SIRAHMED VILLAGE Elementary Mixed 38,725 7,745 30,980 7,745 7,745 30,980 123,919 -

Central-Karachi

Central-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 1-Kalyana 408130186 GBELS - Elementary Elementary Boys 20,253 4,051 16,202 4,051 4,051 16,202 64,808 16,202 81,010 2 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130163 GBLSS - 11-G NEW KARACHI Middle Boys 24,147 4,829 19,318 4,829 4,829 19,318 77,271 19,318 96,589 3 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130167 GBLSS - MEHDI Middle Boys 11,758 2,352 9,406 2,352 2,352 9,406 37,625 9,406 47,031 4 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130176 GBELS - MATHODIST Elementary Boys 20,492 4,098 12,295 8,197 4,098 16,394 65,576 16,394 81,970 5 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 6-Hakim Ahsan 408130205 GBELS - PIXY DALE 2 Registred as a Seconda Elementary Girls 61,338 12,268 49,070 12,268 12,268 49,070 196,281 49,070 245,351 6 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 9-Khameeso Goth 408130174 GBLSS - KHAMISO GOTH Middle Mixed 6,962 1,392 5,569 1,392 1,392 5,569 22,278 5,569 27,847 7 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130160 GBLSS - FARZANA Middle Boys 11,678 2,336 9,342 2,336 2,336 9,342 37,369 9,342 46,711 8 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130166 GBLSS - 5/J Middle Boys 28,064 5,613 16,838 11,226 5,613 22,451 89,804 22,451 112,256 9 Central Karachi New Karachi -

Roulette Strategy 618 Players' Favorite Online Casinos

RRoouulleettttee SSttrraatteeggyy 661188 PPllaayyeerrss’’ FFaavvoorriittee OOnnlliinnee CCaassiinnooss Russell Hunter Publishing Roulette Strategy 618 Players’ Favorite Online Casinos COPYRIGHT © 2016 by Russell Hunter Publishing All rights reserved. Except for brief passages used in legitimate reviews, no parts of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the publisher. Address all inquiries to the publisher: Russell Hunter Publishing Inc. 848 N. Rainbow Blvd., Suite 601 Las Vegas, Nevada 89107 United States of America Web Sites: www.GamblersBookcase.com www.KillerGamblingStrategies.com www.KnockoutSystems.com YouTube: Channel: Gamblers Bookcase Published in the United States of America The material contained in this book is intended to inform and educate the reader and in no way represents an inducement to gamble legally or illegally. Roulette Strategy 618 Players’ Favorite Online Casinos © 2016 Russell Hunter Publishing All Rights Reserved. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS How We Picked the Best Online Casinos 4 How to Win at Online Gambling 5 The Best Online Bonuses in Our Selected Group of Casinos 19 The Best Online Roulette Casinos 20 Roulette Strategy 618 Players’ Favorite Online Casinos © 2016 Russell Hunter Publishing All Rights Reserved 3 How We Picked the Best Online RouletteCasinos We found what we believe are the best online casinos. First, we checked to see if the casino was still accepting U.S. players. Only casinos still open to U.S. players made our list. We also considered the bonuses paid by the casinos, the software offered, the casino's reputation and the casino's payback percentages into consideration in coming up with this list. -

Hblbankbranches.Pdf

CITY WISE LIST OF HBL BRANCHES DESIGNATED FOR DHA CITY COLLECTION KARACHI 1 Dhoraji Colony Branch 1069 2 Yousuf Plaza Branch 1115 3 Nazimabad Commercial Area Branch 1117 4 Shahra-e-Pakistan Branch 1118 5 Hasan Square Branch 1178 6 Malir cantt. Branch 1217 7 P.E.C.H.S. Commercial Centre Branch 1220 8 Abdullah Haroon Road Branch 1403 9 Gulshan Block 5 Branch 1549 10 Korangi No. 2 Branch 1642 11 Shahra-e-Jahangir Branch 1679 12 Ghaffar Goth Branch 1757 13 Abul Hassan Isphani 2214 14 Gujjar Chowk - Manzoor Colony Branch 2289 15 Landhi Industrial Area Branch 0019 16 Liaquatabad Branch 0020 17 Nazimabad Branch 0024 18 Nursery Branch 0027 19 P.A.F. Shahra-e-Faisal Branch 0028 20 Paposhnagar Branch 0053 21 Azizabad Branch 0063 22 Jinnah Terminal Branch 0064 23 Mehran - Malir Halt Branch 0300 24 Orangi Town Branch 0369 25 Muslim Town Branch 0400 26 Sir Syed Road Branch 0490 27 Barkat-e-Hyderi Branch 0502 28 Bahadurabad Branch 0526 29 Korangi No. 5 Branch 0550 30 Shaheed-e-Millat Branch 0599 31 Ibrahim Hyderi Branch 0622 32 Gulistan-e-Jouhar Branch 0857 33 Dastagir Colony Branch 0878 34 University Road Branch 0879 35 Mahmoodabad Branch 0891 36 Karsaz Branch 0896 37 Annexe Branch 0047 38 Baddar Commercial Branch 1155 39 Clifton Branch 0056 40 D.H.A. Branch 0541 41 Elphinstone Street Branch 0044 42 High Court Branch 0606 43 Hotel Mehran Branch 1059 44 Iddgah Branch 0008 45 J.P.M.C. Branch 0065 46 Jacoblines Branch 1089 47 Jodia Bazar Branch 0692 48 K.M.C. -

Public Notice Auction of Gold Ornament & Valuables

PUBLIC NOTICE AUCTION OF GOLD ORNAMENT & VALUABLES Finance facilities were extended by JS Bank Limited to its customers mentioned below against the security of deposit and pledge of Gold ornaments/valuables. The customers have neglected and failed to repay the finances extended to them by JS Bank Limited along with the mark-up thereon. The current outstanding liability of such customers is mentioned below. Notice is hereby given to the under mentioned customers that if payment of the entire outstanding amount of finance along with mark-up is not made by them to JS Bank Limited within 15 days of the publication of this notice, JS Bank Limited shall auction the Gold ornaments/valuables after issuing public notice regarding the date and time of the public auction and the proceeds realized from such auction shall be applied towards the outstanding amount due and payable by the customers to JS Bank Limited. No further public notice shall be issued to call upon the customers to make payment of the outstanding amounts due and payable to JS Bank as mentioned hereunder: Customer ID Customer Name Address Amount as of 8th April 1038553 ZAHID HUSSAIN MUHALLA MASANDPURSHI KARPUR SHIKARPUR 343283.35 1012051 ZEESHAN ALI HYDERI MUHALLA SHIKA RPUR SHIKARPUR PK SHIKARPUR 409988.71 1008854 NANIK RAM VILLAGE JARWAR PSOT OFFICE JARWAR GHOTKI 65110 PAK SITAN GHOTKI 608446.89 999474 DARYA KHAN THENDA PO HABIB KOT TALUKA LAKHI DISTRICT SHIKARPU R 781000 SHIKARPUR PAKISTAN SHIKARPUR 361156.69 352105 ABDUL JABBAR FAZALEELAHI ESTATE S HOP NO C12 BLOCK 3 SAADI TOWN -

Pdf (Accessed: 3 June, 2014) 17

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 The Production and Reception of gender- based content in Pakistani Television Culture Munira Cheema DPhil Thesis University of Sussex (June 2015) 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted, either in the same or in a different form, to this or any other university for a degree. Signature:………………….. 3 Acknowledgements Special thanks to: My supervisors, Dr Kate Lacey and Dr Kate O’Riordan, for their infinite patience as they answered my endless queries in the course of this thesis. Their open-door policy and expert guidance ensured that I always stayed on track. This PhD was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. My mother, for providing me with profound counselling, perpetual support and for tirelessly watching over my daughter as I scrambled to meet deadlines. This thesis could not have been completed without her. My husband Nauman, and daughter Zara, who learnt to stay out of the way during my ‘study time’. -

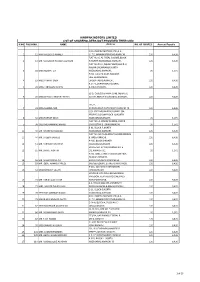

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR.