View of Sales Tax, Per a Synchronized Reading of the Sindh Sales Tax on Services Act 2011 (“Act”) with the Doctrine of Mutuality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronologica Dictionary of Sind Chronologial Dictionary of Sind

CHRONOLOGICA DICTIONARY OF SIND CHRONOLOGIAL DICTIONARY OF SIND (From Geological Times to 1539 A.D.) By M. H. Panhwar Institute of Sindhology University of Sind, Jamshoro Sind-Pakistan All rights reserved. Copyright (c) M. H. Panhwar 1983. Institute of Sindhology Publication No. 99 > First printed — 1983 No. of Copies 2000 40 0-0 Price ^Pt&AW&Q Published By Institute of Sindhlogy, University of Sind Jamshoro, in collabortion with Academy of letters Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Education Islamabad. Printed at Educational Press Dr. Ziauddin Ahmad Road, Karachi. • PUBLISHER'S NOTE Institute of Sindhology is engaged in publishing informative material on - Sind under its scheme of "Documentation, Information and Source material on Sind". The present work is part of this scheme, and is being presented for benefit of all those interested in Sindhological Studies. The Institute has already pulished the following informative material on Sind, which has received due recognition in literary circles. 1. Catalogue of religious literature. 2. Catalogue of Sindhi Magazines and Journals. 3. Directory of Sindhi writers 1943-1973. 4. Source material on Sind. 5. Linguist geography of Sind. 6. Historical geography of Sind. The "Chronological Dictionary of Sind" containing 531 pages, 46 maps 14 charts and 130 figures is one of such publications. The text is arranged year by year, giving incidents, sources and analytical discussions. An elaborate bibliography and index: increases the usefulness of the book. The maps and photographs give pictographic history of Sind and have their own place. Sindhology has also published a number of articles of Mr. M.H. Panhwar, referred in the introduction in the journal Sindhology, to make available to the reader all new information collected, while the book was in press. -

OICCI CSR Report 2018-2019

COMBINING THE POWER OF SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2018-19 03 Foreword CONTENTS 05 OICCI Members’ CSR Impact 06 CSR Footprint – Members’ Participation In Focus Areas 07 CSR Footprint – Geographic Spread of CSR Activities 90 Snapshot of Participants’ CSR Activities 96 Social Sector Partners DISCLAIMER The report has been prepared by the Overseas Investors Chamber of Commerce and Industry (OICCI) based on data/information provided by participating companies. The OICCI is not liable for incorrect representation, if any, relating to a company or its activities. 02 | OICCI FOREWORD The landscape of CSR initiatives and activities is actively supported health and nutrition related initiatives We are pleased to present improving rapidly as the corporate sector in Pakistan has through donations to reputable hospitals, medical care been widely adopting the CSR and Sustainability camps and health awareness campaigns. Infrastructure OICCI members practices and making them permanent feature of the Development was also one of the growing areas of consolidated 2018-19 businesses. The social areas such as education, human interest for 65% of the members who assisted communi- capital development, healthcare, nutrition, environment ties in the vicinity of their respective major operating Corporate Social and infrastructure development are the main focus of the facilities. businesses to reach out to the underprivileged sections of Responsibility (CSR) the population. The readers will be pleased to note that 79% of our member companies also promoted the “OICCI Women” Report, highlighting the We, at OICCI, are privileged to have about 200 leading initiative towards increasing level of Women Empower- foreign investors among our membership who besides ment/Gender Equality. -

Judicial Law-Making: an Analysis of Case Law on Khul' in Pakistan

Judicial Law-Making: An Analysis of Case Law on Khul‘ in Pakistan Muhammad Munir* Abstract This work analyses case law regarding khul‘ in Pakistan. It is argued that Balqis Fatima and Khurshid Bibi cases are the best examples of judicial law- making for protecting the rights of women in the domain of personal law in Pakistan. The Courts have established that when the husband is the cause of marital discord, then he should not be given any compensation; and that the mere filing of a suit for khul‘ by the wife means that hatred and aversion have reached a degree sufficient for courts to grant her the separation she is seeking by resorting to her right of khul‘. The new interpretation of section 10(4) of the West Pakistan Family Courts Act, 1964 by Courts in Pakistan is highly commendable. Key words: khul‘, Pakistan, Muslim personal law, judicial khul‘, case law. * [email protected] The author, is Associate Professor at Faculty of Shari‘a & Law, International Islamic University, Islamabad, and Visiting Professor of Jurisprudence and Islamic Law at the University College, Islamabad. He wishes to thank Yaser Aman Khan and Hafiz Muhammad Usman for their help. He is very thankful to Professor Brady Coleman and Muhammad Zaheer Abbas for editing this work. The quotations from the Qur’an in this work are taken, unless otherwise indicated, from the English translation by Muhammad Asad, The Message of the Qur’an (Wiltshire: Dar Al-Andalus, 1984, reprinted 1997). Islamabad Law Review Introduction The superior Courts in Pakistan have pioneered judicial activism1 regarding khul‘. -

View November Edition 2015 This Edition's Theme Is Based on the Evolution of Our Banking Industry

2015 NOVEMBER 2015 The Art of The Art of Evolution Evolution Fulfilling Promises Soneri Mehnat Wasool 06 in the year 2015 Soneri Roshni, Published by Marketing Department, COK, Karachi. Email us your feedback/comments at: [email protected] Turning Miles into Smiles 19 Soneri Car Finance Launch Sonerians Celebrate 26 Independence Day Enabling The Future: 24/7 Phone Banking: 021-111-SONERI (766374) Soneri Graduate Over 240 branches & 262 ATMs www.soneribank.com 37 SoneriBankPK @SoneriBank_Pk Training Program 03 Editor’s Note 04 Sub-Editor’s Note 05 A Numbers Game 06 Fulfilling Promises - Soneri Mehnat Wasool in the year 2015 18 New Branch Brightens Soneri’s Presence in Lahore 19 Turning Miles into Smiles - Soneri Car Finance Launch 21 In Focus: Soneri Car Finance 22 Flying Colors - Deposit Mobilization 2015 Campaign Results 24 Contingency – Soneri Bank’s Business Continuity Plan (BCP) 26 Sonerians Celebrate Independence Day 34 Risk Minds Asia 2015 35 Credit Administration Department - The Milestone 37 Enabling The Future: Soneri Graduate Training Program 38 Iftar in the Name of Mustaqeem 39 Revolutionizing Banking through Technology 40 The Soneri Sportsmanship 41 Latest in Technology 43 Celebrating Summers: Mango Fiesta 2015 44 PTCL & Soneri Bank IT Department Signing Ceremony 45 Soneri Meets C-Square 46 Lighting the Path to Mobile Banking 47 The 2nd Term Finance Certificates Listed at Karachi Stock Exchange 48 Keeping Up with the Soneri High Moral Standards Code 49 Setting a Footprint in Golf 50 Enlightening Lives with Easy Banking 55 A Helping Hand for the Youth - Prime Minister’s Youth Business Loan Scheme 56 Soneri Winnings at Jeeto Pakistan 57 Digital Matters Editor’s Note Dear Sonerians, The year of 2015 has almost come to a close, with the announcement of our third quarter profit results of Rs.2,622.22 million before tax and profit after tax of Rs.1,589.87 million for the nine months period ended 30 September 2015. -

C.A. 1095 2018 13092019

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) PRESENT: MR. JUSTICE ASIF SAEED KHAN KHOSA, CJ MR. JUSTICE FAISAL ARAB MR. JUSTICE IJAZ UL AHSAN CIVIL APPEALS NO. 1095-1097 and 1021-1026 OF 2018 (against the judgment dated 05.03.2018 passed in C.P. No. D-5812/2015, etc. by the High Court of Sindh, Karachi) AND CIVIL APPEAL NO. 134-L OF 2018 AND CIVIL PETITION NO. 1362 OF 2019 (against the judgments dated 05.04.2018 passed in W.P. No. 29724/2015, etc. and 30822/2015, respectively, by the Lahore High Court, Lahore) AND CIVIL APPEALS NO. 1138, 1154-1158, 1486 AND 1487 OF 2018 (against the judgment dated 03.09.2018 passed in C.P. No. D-6274/2017, etc. by the High Court of Sindh, Karachi) AND CIVIL PETITIONS NO. 4475 AND 4476 OF 2018 (against the order dated 19.11.2018 passed in C.M.A. No. 33322/2018 by the High Court of Sindh, Karachi AND CRIMINAL ORIGINAL PETITIONS NO. 14 AND 18 OF 2019 (Non-compliance of this Court’s order dated 10.01.2019 passed in C.A. No. 1095/2018) CRIMINAL ORIGINAL PETITIONS NO. 25 AND 26 OF 2019 (Non-compliance of this Court’s order dated 01.10.2018 passed in C.P. No.3620 and 3623/2018) AND CIVIL REVIEW PETITIONS NO. 20, 37 TO 49 AND 77 OF 2019 (Review against this Court’s order dated 13.12.2018 passed in C.A. No. 1023- 1025, 1138, 1154-1158, 1486-1487, 134-L/2018 and C.P. -

Law Review Islamabad

Islamabad Law Review ISSN 1992-5018 Volume 1, Number 1 January – March 2017 Title Quarterly Research Journal of the Faculty of Shariah & Law International Islamic University, Islamabad ISSN 1992-5018 Islamabad Law Review Quarterly Research Journal of Faculty of Shariah& Law, International Islamic University, Islamabad Volume 1, Number 1, January – March 2017 Islamabad Law Review ISSN 1992-5018 Volume 1, Number 1 January – March 2017 The Islamabad Law Review (ISSN 1992-5018) is a high quality open access peer reviewed quarterly research journal of the Faculty of Shariah & Law, International Islamic University Islamabad. The Law Review provides a platform for the researchers, academicians, professionals, practitioners and students of law and allied fields from all over the world to impart and share knowledge in the form of high quality empirical and theoretical research papers, essays, short notes/case comments, and book reviews. The Law Review also seeks to improve the law and its administration by providing a forum that identifies contemporary issues, proposes concrete means to accomplish change, and evaluates the impact of law reform, especially within the context of Islamic law. The Islamabad Law Review publishes research in the field of law and allied fields like political science, international relations, policy studies, and gender studies. Local and foreign writers are welcomed to write on Islamic law, international law, criminal law, administrative law, constitutional law, human rights law, intellectual property law, corporate law, competition law, consumer protection law, cyber law, trade law, investment law, family law, comparative law, conflict of laws, jurisprudence, environmental law, tax law, media law or any other issues that interest lawyers the world over. -

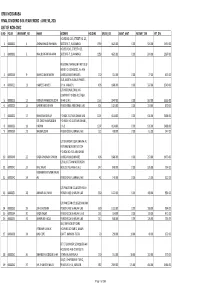

List of Non-CNIC Certificate Holders Final Dividend 2016 31102016.Xlsx

ORIX MODARABA FINAL DIVIDEND 34% YEAR ENDED : JUNE 30, 2016 LIST OF NON-CNIC S.NO FOLIO WARRANT_NO NAME ADDRESS HOLDING GROSS_DIV ZAKAT_AMT INCOME_TAX NET_DIV HOUSE NO. 243, STREET NO. 23, 1 0000002 1 AYSHA KHALID RAHMAN SECTOR E-7, ISLAMABAD. 1359 4621.00 0.00 924.00 3697.00 HOUSE # 243, STREET # 23, 2 0000003 2 KHALID IRFAN RAHMAN SECTOR E-7, ISLAMABAD. 1359 4621.00 0.00 924.00 3697.00 REGIONAL MANAGER FIRST GULF BANK P.O. BOX 18781, AL-AIN 3 0000016 9 SHAHID AMIN SHEIKH UNITED ARAB EMIRATES. 150 510.00 0.00 77.00 433.00 15-B, NORTH AVENUE PHASE I, 4 0000021 11 HAMEED AHMED D.H.A. KARACHI. 496 1686.00 0.00 337.00 1349.00 C/O NATIONAL DRILLING COMPANY P O BOX 4017 ABU 5 0000023 12 MOHSIN HAMEEDDUDDIN DHABI U.A.E. 1161 3947.00 0.00 592.00 3355.00 6 0000025 13 BABER SAEED KHAN PO BOX 3865 ABU DHABI UAE 301 1023.00 0.00 153.00 870.00 7 0000032 17 SHAKEELA BEGUM P.O BOX 2157 ABU DHABI UAE 1207 4104.00 0.00 616.00 3488.00 DR. SYED SHAMSUDDIN P.O. BOX. NO.2157 ABU DHABI., 8 0000033 18 HASHMI U.A.E. 1207 4104.00 0.00 616.00 3488.00 9 0000039 21 NAEEMUDDIN PO BOX 293 FUJAIRAH U.A.E. 120 408.00 0.00 61.00 347.00 C/O SIKANDER IQBAL SHAIKH AL FUTTAIM MOTORS TOYOTA P.O.BOX NO. 555 ABU DHABI 10 0000040 22 RAZIA SHABNAM SHAIKH UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 496 1686.00 0.00 253.00 1433.00 C/O AL FUTTAIM MOTORS PO 11 0000041 23 RIAZ JAVAID BOX 293 FUJAIRAH U.A.E. -

Balkanisation and Political Economy of Pakistan by Yousuf Nazar

BALKANISATION AND POLITICAL ECONOMY OF PAKISTAN YOUSUF NAZAR FOREWORD DR MUBASHIR HASAN @ Copyrights reserved with the author First published in 2008 Revised edition 2011 Published by National News Agency 164 A.M Asad Chamber, Ground Floor, Near Passport Office, Saddar, Karachi, Pakistan. Tel: 021-3568828, 35681520 Fax: 021-35682391 web: www.nnagency.com Email: [email protected] Official Correspondence 4-C, 14th Commercial Street, D.H.A., Phase II Ext., Karachi, Pakistan. Tel: 021-35805391-3 Email: [email protected] Produced and design by Mirador Printed by Elliya Printers This book is dedicated to those 60%-70% Pakistanis who live in poverty and survive on less than 2 Dollars a day About the author Yousuf Nazar is an international finance professional with specialisation in emerging economies. As the head of Citigroup’s emerging markets public equity investments unit based in London from 2001 to 2005, he helped Citigroup manage its over US $2 billion proprietary equity portfolio in the emerging markets of Asia, Latin America, Central/Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa. Before this assignment, he also served as a Director of Citibank’s strategic planning group during the 1990s. Since 2006, he has written many articles on Pakistan’s political and economic issues with a particular focus on the developments in an international context. His interest in politics dates back to his student days as a political activist when he worked against General Zia-ul Haq’s martial law in 1977. His experience in the developing countries spanned across several areas of international finance. He did his Bachelor's degree in administrative studies and an MBA in international finance and economics from York University in Toronto. -

Kurrachee (Karachi) Past: Present and Future

KURRACHEE (KARACHI) PAST: PRESENT AND FUTURE ALEXANDER F. BAILLIE, F.R.G.S., 1880 BIRD'S EYE VIEW OF VICTORIA ROAD CLERK STREET, SADDAR BAZAR KARACHI REPRODUCED BY SANI H. PANHWAR (2019) KUR R A CH EE: PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. KUR R A CH EE: (KA R A CH I) PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. BY A LEXA NDER F.B A ILLIE,F.R.G.S., A uthor of"A PA RA GUA YA N TREA SURE,"etc. W ith M a ps,Pla ns & Photogra phs 1890. Reproduced by Sa niH .Panhw a r (2019) TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE GRANT-DUFF, P.C., G.C.S.I., C.I.E., F.R.S., M.R.A.S., PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, FORMERLY UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA, AND GOVERNOR OF THE PROVINCE OF MADRAS, ETC., ETC., THIS ACCOUNT OF KURRACHEE: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE, IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. INTRODUCTION. THE main objects that I have had in view in publishing a Treatise on Kurrachee are, in the first place, to submit to the Public a succinct collection of facts relating to that City and Port which, at a future period, it might be difficult to retrieve from the records of the Past ; and secondly, to advocate the construction of a Railway system connecting the GateofCentralAsiaand the Valley of the Indus, with the Native Capital of India. I have elsewhere mentioned the authorities to whom I am indebted, and have gratefully acknowledged the valuable assistance that, from numerous sources, has been afforded to me in the compilation of this Work; but an apology is due to my Readers for the comments and discursions that have been interpolated, and which I find, on revisal, occupy a considerable number of the following pages. -

Part 5 Sindh

Environmentalw ain Pakistan L Governing Natural Resources and the Processes and Institutions That Affect Them Part 5 Sindh Environmental Law in Pakistan Governing Natural Resources and the Processes and w in Pakistan Institutions That Affect Them Sindh Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction to the Series .................................................................................................... 6 Foreword................................................................................................................................ 7 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. 9 1. Legislative Jurisdiction ............................................................................................ 10 1.1 Natural Resources .....................................................................................................................10 1.2 Processes and Institutions.........................................................................................................12 2. Methodology.............................................................................................................. 18 3. Hierarchy of Legal Instruments ............................................................................... 19 3.1 Legislative Acts..........................................................................................................................19 -

Newsletterletter the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan

Governance, Transparency and Service to Members & Students www.icap.org.pk Volume 34 Issue 2 February 2011 NewsNewsletterletter The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan 2011 GOLDEN JUBILEE YEAR MEETINGS N EVENTS FIVE DECADES OF UPHOLDING INTEGRITY, INCULCATING PROFESSIONALISM AND ENHANCING QUALITY Inside Meetings n Events Gold Medal and Award Distribution Ceremony CFO Conferences 2011 in Karachi & Lahore Paying respect to the National Anthem Seminar on Risk Management & Basel II - Inaugural Ceremony of Golden Jubilee Deriving Value beyond Compliance Celebration Fifty years ago on the 3rd of March, the Chartered Accountants Role of Chartered Accountants in Building Ordinance 1961 received assent of the President of Pakistan which Successful Organizations set the foundation of our Institute. Keeping in mind the historic affiliation, Friday 4th of March 2011 was chosen to inaugurate the ICAP Golden Jubilee Golf Tournament celebrations of the Golden Jubilee Year at Serena Hotel Islamabad. Family Get Together The ceremony Honorable Minister of Finance, Dr. Abdul Hafeez Sheikh graced the occasion as the Chief Guest, with Vice Chancellor Beacon House National University Mr. Sartaj Aziz and the Auditor Members Section General of Reconstitution of the Quality Assurance Pakistan, Mr. Board (QAB) Tanwir Ali Agha doing Medical Insurance - Are you covered? honors as key note Technical Update speakers. More than Students Section 650 well wishers ACTEPR Education Fair 2011 including members, Computer Practical Examination The Chief Guest Dr. Abdul Hafeez Sheikh addressing the gathering diplomats NewsletterThe Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan and media personnel had assembled to witness the Inaugural Ceremony of the Golden Jubilee celebrations. The Chief Guest of the evening Dr. -

Olitical Amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of olitical amphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Parts 1-4 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA fc I A Guide to the Microfiche Collection POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Associate Editor and Guide compiled by August A. Imholtz, Jr. A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicaîion Data: Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by a printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-55655-206-8 (microfiche) 1. Political parties-India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1I527 1989<MicRR> 324.254~dc20 89-70560 CIP International Standard Book Number: 1-55655-206-8 UPA An Imprint of Congressional Information Service 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD20814 © 1989 by University Publications of America Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. TABLE ©F COMTEmn Introduction v Note from the Publisher ix Reference Bibliography Part 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups India Congress Committee. (Including All India Congress Committee): 1-282 ... 1 Communist Party of India: 283-465 17 Communist Party of India, (Marxist), and Other Communist Parties: 466-530 ... 27 Praja Socialist Party: 531-593 31 Other Socialist Parties: