Some Effects of Conversion from Streetcar to Subway Transit Lines in Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Canada Railway Society the Cover

Upper Canada Railway Society The Cover Rapid transit comes to tbe suburbs I A westbound TTC Bloor-Danforth train is sbown bere on tbe newly-opened eastern extension of tbe subway, between Warden and Victoria Park Stations. It is skirting Bell's Busb Park and tbe Massey Creek Ravine — scenery wbicb no doubt newsletter comes as a pleasant surprise to many commuters formerly used to traffic jams on their way to work. See page 55. Number 268 May, 1968 — Ted Wickson Published monthly by the Upper Canada Railway Society, Inc., Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto, Ont. Coming Events James A. Brown, Editor ^xo:OT•^x•:•x•>x•:•>^>^^^^:•:•^^^^:^^ Regular meetings of the Society are held on the third Friday of each month (except July and August) at 589 Mt. Pleasant Road, Authorized as Second Class Matter by the Post Office Department, Toronto, Ontario. 8.00 p.m. Ottawa, Ont. and for payment of postage In cash. Members are asked to give the Society at least five weeks notice June 1: Steam excursion to Stratford, leaves Toronto of address changes. (Sat) at 0815 EDT. FARES: Adult S9.75; Child S5.00; Infant $1.00. June 9: A visit to tbe OERHA property at Rockwood is (Sun) being arranged. Write tbe Entertainment Com• Please address NEWSLETTER contributions to the Editor at mittee for details. 3 Bromley Crescent, Bramalea, Ontario. No responsibility is June 13: NOTE CHANGE OF DATE! assumed for loss or nonreturn of material. (Tburs) Outdoor meeting: A visit to CN's new Express Terminal at Toronto Yard, Keele Street at Hwy All other Society business, including membership Inquiries, should 7. -

Toronto Subway System, ON

Canadian Geotechnical Society Canadian Geotechnical Achievements 2017 Toronto Subway System Geotechnical Investigation and Design of Tunnels Geographical location Key References Wong, JW. 1981. Geotechnical/ Toronto, Ontario geological aspects of the Toronto subway system. Toronto Transit Commission. When it began or was completed Walters, DL, Main, A, Palmer, S, Construction began in 1949 and continues today. Westland, J, and Bihendi, H. 2011. Managing subsurface risk for Toronto- York Spadina Subway extension project. Why a Canadian geotechnical achievement? 2011 Pan-Am and CGS Geotechnical Conference. Construction of the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) subway system, the first in Canada, began in 1949 and currently consists Photograph and Map of four subway lines. In total there are currently approximately 68 km of subway tracks and 69 stations. Over one million trips are taken daily on the TTC during weekdays. The subway system has been expanded in several stages, from 1954, when the first line (the Yonge Line) was opened, to 2002, when the most recently completed line (the Sheppard Line) was opened. Currently the Toronto-York Spadina Subway Extension is under construction. The subway tunnels have been constructed using a number of different technologies over the years including: open cut excavation, open/closed shield tunneling under ambient air pressure and compressed air, hand mining and earth pressurized tunnel boring machines. The subway tunnels range in design from reinforced concrete box structures to approximately 6 m diameter precast concrete segmental liners or cast iron segmental liners. Looking east inside newly constructed TTC subway The tunnels have been advanced through various geological tunnel, 1968. (City of Toronto Archives) formations: from hard glacial tills to saturated alluvial sands and silts, and from glaciolacustrine clays to shale bedrock. -

Rapid Transit in Toronto Levyrapidtransit.Ca TABLE of CONTENTS

The Neptis Foundation has collaborated with Edward J. Levy to publish this history of rapid transit proposals for the City of Toronto. Given Neptis’s focus on regional issues, we have supported Levy’s work because it demon- strates clearly that regional rapid transit cannot function eff ectively without a well-designed network at the core of the region. Toronto does not yet have such a network, as you will discover through the maps and historical photographs in this interactive web-book. We hope the material will contribute to ongoing debates on the need to create such a network. This web-book would not been produced without the vital eff orts of Philippa Campsie and Brent Gilliard, who have worked with Mr. Levy over two years to organize, edit, and present the volumes of text and illustrations. 1 Rapid Transit in Toronto levyrapidtransit.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 About this Book 9 Edward J. Levy 11 A Note from the Neptis Foundation 13 Author’s Note 16 Author’s Guiding Principle: The Need for a Network 18 Executive Summary 24 PART ONE: EARLY PLANNING FOR RAPID TRANSIT 1909 – 1945 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNING OF RAPID TRANSIT PLANNING IN TORONTO 25 1.0 Summary 26 1.1 The Story Begins 29 1.2 The First Subway Proposal 32 1.3 The Jacobs & Davies Report: Prescient but Premature 34 1.4 Putting the Proposal in Context CHAPTER 2: “The Rapid Transit System of the Future” and a Look Ahead, 1911 – 1913 36 2.0 Summary 37 2.1 The Evolving Vision, 1911 40 2.2 The Arnold Report: The Subway Alternative, 1912 44 2.3 Crossing the Valley CHAPTER 3: R.C. -

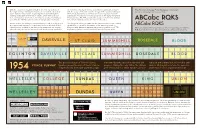

TTC Typography History

With the exception of Eglinton Station, 11 of the 12 stations of The intention of using Helvetica and Univers is unknown, however The Toronto Subway Font (Designer Unknown) the original Yonge Subway line have been renovated extensively. with the usage of the latter on the design of the Spadina Subway in Based on Futura by Paul Renner (1928) Some stations retained the original typefaces but with tighter 1978, it may have been an internal decision to try and assimilate tracking and subtle differences in weight, while other stations subsequent renovations of existing stations in the aging Yonge and were renovated so poorly there no longer is a sense of simplicity University lines. The TTC avoided the usage of the Toronto Subway seen with the 1954 designs in terms of typographical harmony. font on new subway stations for over two decades. ABCabc RQKS Queen Station, for example, used Helvetica (LT Std 75 Bold) in such The Sheppard Subway in 2002 saw the return of the Toronto Subway an irresponsible manner; it is repulsively inconsistent with all the typeface as it is used for the names of the stations posted on ABCabc RQKS other stations, and due to the renovators preserving the original platfrom level. Helvetica became the primary typeface for all TTC There are subtle differences between the two typefaces, notably the glass tile trim, the font weight itself looks botched and unsuitable. wayfinding signages and informational material system-wide. R, Q, K, and S; most have different terminals, spines, and junctions. ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL BLOOR DANGER DA N GER Danger DO NOT ENTER Do Not Enter Do Not Enter DAVISVILLE ST CL AIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR EGLINTON DAVISVILLE ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR EGLINTON DAVISVILLE ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR The specially-designed Toronto Subway that embodied the spirit of modernism and replaced with a brutal mix of Helvetica and YONGE SUBWAY typeface graced the walls of the 12 stations, progress. -

Relief Line Update

Relief Line Update Mathieu Goetzke, Vice-President, Planning David Phalp, Manager, Rapid Transit Planning FEBRUARY 7, 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Relief Line South alignment identified by the City of Toronto as preferred, has a Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR) above 1.0, demonstrating the project’s value; however, since it is close to 1.0, it is highly sensitive to costs, so more detailed design work and procurement method choice will be of importance to maintain or improve this initial BCR. • Forecasts suggest that Relief Line South will attract ridership to unequivocally justify subway-level service; transit-oriented development opportunities can further boost ridership. • Transit network forecasts show that Relief Line South needs to be in operation before the Yonge North Subway Extension. Relief Line North provides further crowding relief for Line 1. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 2 SUBWAY EXPANSION - PROJECT STATUS Both Relief Line North and South and the Yonge North Subway Extension are priority projects included in the 2041 Regional Transportation Plan. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 3 RELIEF LINE SOUTH: Initial Business Case Alignments Evaluated • Metrolinx is developing an Initial Business Case on Relief Line South, evaluating six alignments according to the Metrolinx Business Case Guidance and the Auditor General’s 2018 recommendations • Toronto City Council approved the advancement of alignment “A” (Pape- Queen via Carlaw & Eastern) • Statement of Completion of the Transit Project Assessment Process (TPAP) received October 24, 2018. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 4 RELIEF -

Service Improvements for 2002

SERVICE IMPROVEMENTS FOR 2002 Subway Streetcars Buses RT October 2001 Service Improvements for 2002 - 2 - Table of contents Table of contents Summary................................................................................................................................................................4 Recommendations ..............................................................................................................................................5 1. Planning transit service ...............................................................................................................................6 2. Recommended new and revised services for the Sheppard Subway .......................................10 Sheppard Subway.................................................................................................................................................................................10 11 BAYVIEW – Service to Bayview Station...........................................................................................................................................10 25 DON MILLS – Service to Don Mills Station ....................................................................................................................................11 Don Mills/Scarborough Centre – New limited-stop rocket route ....................................................................................................11 Finch East – Service to Don Mills Station...........................................................................................................................................11 -

Toronto Subway Air Quality Health Impact Assessment

Toronto Subway Air Quality Health Impact Assessment Prepared for: Toronto Public Health City of Toronto November 15, 2019 Toronto Subway Air Quality Health Impact Assessment Project Summary Introduction Toronto’s subway is a critical part of the Toronto Transit Commission’s (TTC) public transportation network. First opened in 1954, it spans over 77 km of track and 75 stations across the city. On an average weekday over 1,400,000 customer-trips are taken on the subway. In 2017, Health Canada reported levels of air pollution in the TTC subway system that were elevated compared with outdoor air. The Toronto Board of Health requested that Toronto Public Health (TPH) oversee an independent study to understand the potential health impacts of air quality issues for passengers in the Toronto subway system - The Toronto Subway Air Quality Health Impact Assessment (TSAQ HIA). The TSAQ HIA takes a holistic approach to assessing how subway use may positively and/or negatively impact the health and well-being of Torontonians. The HIA used a human health risk assessment (HHRA) approach to calculate the potential health risks from exposure to air pollutants in the subway, and the results of the HHRA were incorporated into the HIA. The TSAQ HIA sought to answer three overarching questions: 1. What is the potential health risk to current passengers from air pollutants in the subway system? 2. What are the potential health benefits to mitigation measures that could be implemented to improve air quality in the TTC subway system? 3. What is the overall impact of the TTC’s subway system on the health and well-being of Torontonians? Results of the Toronto Subway Air Qualty Health Impact Assessment The TSAQ HIA assessed the overall impact of subway use on the health and well-being of Torontonians. -

July 2018 Activity Calendar

Activity Calendar July 2017 You must sign up for all activities www.studyquest.net/studentarea.htm Day Date Name Description Cost Meeting place Sun 1 ! Happy Canada Day!! ! Celebrate Canada's birthday at Downsview Park with live entertainment, games, face painting, Sun 1 Canada Day Celebration! FREE College Station @ 5PM and an incredible fireworks display! Mon 2 No Class today! See you on Tuesday! Kensington Market and Check out the delicious (and cheap!) food selection, art, crafts, live performances, and more! An Tu e s 3 FREE/ PYOW Quest Lounge @ 4PM China Town awesome place to pick up souvenirs! Watch the Toronto Blue Jays face off against the New York Mets! Experience the excitement of Wed 4 Blue Jays Game $30 Union Station @ 6:30PM watching a baseball game in Canada! Have a blast as you cheer for your favourite team! Come out to Quest’s first ever Karaoke event! Have fun and sing your heart out while your friends Thurs 5 Karaoke at Quest! FREE Quest Lounge @3PM cheer you on! Taste hamburgers from the best burger chefs in Toronto! Located on West Island! Come and enjoy Fri 6 BurgerMania on West Island! FREE/ PYOW Quest Lounge @3PM the live music, desserts, beer (19+), and of course, BURGERS! Vegetarian options also available. Come out to this Award winning event! Enjoy the non-stop Salsa dancing and latin music in the Sat 7 Salsa on Saint Clair Street FREE St. Clair Station @6PM streets alongside some of the best local and international entertainers! Afrofest Is the Largest Free African Music Festival In North America! Enjoy the incredible diversity Sun 8 Afrofest 2018 FREE Woodbine Station @4PM of African music while celebrating and learning about African culture. -

Modernizing the Ttc – a New Approach to Communications, Community Relations and Property Coordination for Construction Projects Action Item

Form Revised: February 2005 TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION REPORT NO. Resubmitted December 19,2012 MEETING DATE: November 21, 2012 SUBJECT: MODERNIZING THE TTC – A NEW APPROACH TO COMMUNICATIONS, COMMUNITY RELATIONS AND PROPERTY COORDINATION FOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS ACTION ITEM RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Commission: 1. Endorse the initiatives outlined in this report establishing the TTC’s new approach for public consultation, community relationships of property coordination for construction projects. 2. Note the actions that have already been implemented to address issues noted in the Ombudsman’s report to Council dated October 31, 2012. FUNDING The recommendations in this report do not have any financial implications. BACKGROUND In January 2012, the Engineering and Construction Branch and the former Transit Expansion Department (Transit City) were amalgamated and renamed the Engineering, Construction and Expansion Group (ECE). The new ECE Group includes the establishment of a separate dedicated department, Strategic Partnerships, responsible for managing communications, community relations and third party, including property requirements for TTC construction projects. This report provides an overview of the Strategic Partnerships activities. DISCUSSION The TTC Capital Program includes about 500 contracts over the next five years. Most of these projects involve maintenance and rehabilitation work related to the state of good repair within TTC facilities (carhouses and garages) that have little or no impact on the MODERNIZING THE TTC – A NEW APPROACH TO COMMUNICATIONS, COMMUNITY RELATIONS AND PROPERTY COORDINATION FOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS Page 2 public. Over the past several years there are an increasing number of construction projects that involve upgrades and enhancements to existing subway stations with more impact on adjacent communities and the 1.6 million people that use the TTC on a daily basis. -

Applying Life Cycle Assessment to Analyze the Environmental Sustainability of Public Transit Modes for the City of Toronto

Applying life cycle assessment to analyze the environmental sustainability of public transit modes for the City of Toronto by Ashton Ruby Taylor A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography & Planning in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2016 Copyright © Ashton Ruby Taylor, 2016 Abstract One challenge related to transit planning is selecting the appropriate mode: bus, light rail transit (LRT), regional express rail (RER), or subway. This project uses data from life cycle assessment to develop a tool to measure energy requirements for different modes of transit, on a per passenger-kilometer basis. For each of the four transit modes listed, a range of energy requirements associated with different vehicle models and manufacturers was developed. The tool demonstrated that there are distinct ranges where specific transit modes are the best choice. Diesel buses are the clear best choice from 7-51 passengers, LRTs make the most sense from 201-427 passengers, and subways are the best choice above 918 passengers. There are a number of other passenger loading ranges where more than one transit mode makes sense; in particular, LRT and RER represent very energy-efficient options for ridership ranging from 200 to 900 passengers. The tool developed in the thesis was used to analyze the Bloor-Danforth subway line in Toronto using estimated ridership for weekday morning peak hours. It was found that ridership across the line is for the most part actually insufficient to justify subways over LRTs or RER. This suggests that extensions to the existing Bloor-Danforth line should consider LRT options, which could service the passenger loads at the ends of the line with far greater energy efficiency. -

TTC Investigation Report

Report October 2012 Tunnel Vision: An Investigation into the Toronto Transit Commission Second Exit Project at Donlands and Greenwood Stations Fiona Crean Ombudsman TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 2.0 The Complaint ........................................................................................................ 7 3.0 The Investigation .................................................................................................... 7 4.0 The Facts 8 4.1 History of the Second Exit Project .................................................................. 8 4.1.1 TTC Reports ................................................................................................... 8 4.1.2 TTC's Preferred Options ................................................................................. 9 4.1.3 TTC Policy – Property Acquisition & Notification Protocol .............................. 9 4.2 Notice to Councillor and Community ............................................................. 10 4.2.1 Community Response to Notice ................................................................... 14 4.2.2 TTC's Response to Notice ............................................................................ 16 4.2.3 Community's Request for Information ........................................................... 17 4.2.4 TTC Meeting with the Owner of Property Y .................................................. 18 4.3 Community Information -

Annual Report 1968

TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT TO THE MUNICIPALITY OF METROPOLITAN TORONTO 1968 RALPH C. DAY TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS RALPH C. DAY, Chairman FORD G. BRAND, Vice-Chairman D. F. HAMILTON J. T. FISHER, Commissioner D. F. HAMILTON, Commissioner b. C. SMYTH, Commissioner OFFICIALS JAMES H. KEARNS, General Manager of Operations W. H. PATERSON, General Manager--Subway Construction H. E. PETTETT, General Secretary R. G. WAITE, Assistant General Manager of Operations JAMES H. KEARNS L. 0. MORLEY, Treasurer 01!·· D. A. ELLIOTT, Q.C., General Counsel H. E. PETTETT . '\"'' J Wm. R. Alien, Esq., Q.C., Chairman And Members of the CGuncil of The Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto City Hall, TORONTO 100. Ladies and Gentlemen: ANNUAL REPORT- 1968 The high point of the year was the opening of the easterly and west erly extensions to the Bloor-Danforth subway. Formal opening ceremonies were held on May 10 and the extensions were opened for passenger service on Saturday, May 11. The easterly extension runs from Woodbine station to Warden station, at St. Clair and Warden Avenues in the Borough of Scarborough, a distance of 2.72 miles. The westerly extension runs from Keele station to Islington station, at Bloor Street West and Islington A venue in the Borough of Etobicoke, a distance of 3.44 miles. The two extensions increased the length of Metro's crosstown subway line to fourteen miles. Passenger response to the new subway extensions has been excellent. Subway riding increased by an estimated 7.7% over 1967. The subway extensions and the accompanying extensive surface route expansion helped to boost the total number of revenue passengers carried by the system to an all-time high, 323,481,655, an increase of 9,068,169 over the previous year.