Conservation and the Crosstown: Exploring the Intersection of Retail Heritage and Transportation Infrastructure in Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

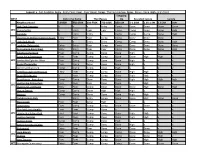

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Fixer Upper, Comp

Legend: x - Not Available, Entry - Entry Point, Fixer - Fixer Upper, Comp - The Compromise, Done - Done + Done, High - High Point Stepping WEST Get in the Game The Masses Up So-called Luxury Luxury Neighbourhood <$550K 550-650K 650-750K 750-850K 850-1M 1-1.25M 1.25-1.5M 1.5-2M 2M+ High Park-Swansea x x x Entry Comp Done Done Done Done W1 Roncesvalles x Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High Parkdale x Entry Entry x Comp Comp Comp Done High Dovercourt Wallace Junction South Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done Done x High Park North x x Entry Entry Comp Comp Done Done High W2 Lambton-Baby point Entry Entry Fixer Comp Comp Done Done Done Done Runnymede-Bloor West Entry Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Done Done Done High Caledonia-Fairbank Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High x x x Corso Italia-Davenport Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High High x W3 Keelesdale-Eglinton West Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High x x x Rockcliffe-Smythe Fixer Comp Done Done Done High x x x Weston-Pellam Park Comp Comp Comp Done High x x x x Beechborough-Greenbrook Entry Fixer Comp Comp Done High High x x BriarHill-Belgravia x Fixer Comp Comp Done High High x x Brookhaven--Amesbury Comp Comp Done Done Done High High High high Humberlea-Pelmo Park Fixer Fixer Fixer Done Done x High x x W4 Maple Leaf and Rustic Entry Fixer Comp Done Done Done High Done High Mount Dennis Comp Comp Done High High High x x x Weston Comp Comp Done Done Done High High x x Yorkdale-Glen Park x Entry Entry Comp Done Done High Done Done Black Creek Fixer Fixer Done High x x x x x Downsview Fixer Comp -

Round 2 Consultation Report 2020-2021, TO360

Consultation Report TO360 Wayfinding Strategy 2020-2021 Public Consultation Round Two March 2021 Table of Contents Background .................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of the local map consultation ................................................................................... 2 Outreach and notification ........................................................................................................... 5 Summary of engagement statistics ........................................................................................... 9 Detailed feedback by local map area....................................................................................... 10 Other feedback about TO360 maps, in general ..................................................................... 19 Next steps ................................................................................................................................... 19 Attachment A: List of organizations invited to participate Attachment B: Round Two Draft Wayfinding Maps Background The Toronto 360 (“TO360”) Wayfinding project is a pedestrian wayfinding system which is a central component of the City’s ambition to make Toronto a more walkable, welcoming and understandable place for visitors and residents alike. TO360 provides consistent wayfinding information through a unified signage and mapping system delivered by the City and project partners. Following the successful completion of -

752 Vaughan Rd 416.291.7372 York, on Christinecowernteam.Com HOODQ HIGHLIGHTS

The Christine Cowern Team 752 Vaughan Rd 416.291.7372 York, ON ChristineCowernTeam.com HOODQ HIGHLIGHTS ELEMENTARY TRANSIT SAFETY SCHOOLS 7.4 8.5 8.5 HIGH PARKS CONVENIENCE SCHOOLS 8.2 9.3 7.5 PUBLIC SCHOOLS (ASSIGNED) Your neighbourhood is part of a community of Public Schools offering Elementary, Middle, and High School programming. See the closest Public Schools near you below: Fairbank Public School about a 3 minute walk - 0.19 KM away Pre-Kindergarten, Kindergarten, Elementary and Middle 2335 Dufferin St, York, ON M6E 3S5, Canada Fairbank Public School serves a very diverse community of families that belong to many races, languages and cultures, which gives the school a social richness that we cultivate and cherish. Our staff is dedicated to creating opportunities for learning that ensure success for all our students. We are constantly learning new concepts and strategies, and challenging ourselves to do the best job possible for our students. We believe that all students can and want to learn, so we emphasize the development of literacy, mathematics, and computer technology skills in all subject areas. Fairbank provides specialized programming in Science, French, Health and Physical Education, Music and Visual Arts. http://www.tdsb.on.ca... Address 2335 Dufferin St, York, ON M6E 3S5, Canada Language English Grade Level Pre-Kindergarten, Kindergarten, Elementary and Middle School Code 6225 School Type Public Phone Number 416-394-2323 School Board Toronto DSB School Number 190918 Grades Offered PK to 8 School Board Number B66052 7.2 SCHOOLQ É Élém Pierre-Elliott-Trudeau SCORE 5.42 KM away Pre-Kindergarten, Kindergarten and Elementary 65 Grace St, Toronto, ON M6J 2S4, Canada / Nous sommes heureux d’accueillir environ 360 élèves de la maternelle à la 6e année dans un milieu sécuritaire où il fait bon apprendre. -

Connecting the Region

EGLINTON CROSSTOWN CONSTRUCTION UPDATE EASTERN WORKS OPEN HOUSE | APRIL 9, 2020 WELCOME Our Eastern Works Open House will feature the following stations and stops: • Science Centre • Aga Khan Park & Museum, Wynford, Sloane, O’Connor • Pharmacy , Hakimi Lebovic, Golden Mile, Birchmount, Ionview • and Kennedy. 2 COVID-19 MANAGEMENT • Crosslinx Transit Solutions (CTS) has been exercising all safety protocols on-site including social distancing. • For more information on CTS’ COVID-19 Management, please visit their website: http://www.crosslinxtransit.ca/wp-content/uploads/CTS_COVID- 19_mobile_v2.png EGLINTON CROSSTOWN LRT PROJECT • A 19-kilometre route separated from regular traffic • 10-kilometres underground; 9-kilometres at surface in east • 15 underground stations and 10 surface stops • A maintenance and storage facility • Transit communications system • Links to 54 bus routes, 3 subway stations, GO Transit, UP Express station PROJECT PROGRESS Maintenance and Storage Facility complete 12 vehicles received 50% of track installed Mining complete at Laird and Oakwood stations Deep excavation underway or complete at all stations 2019 PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS FIRST LIGHT RAIL VEHICLE ON MAINLINE 8 9 10 SCIENCE CENTRE STATION RENDERINGS AERIAL VIEW MAIN ENTRANCE WEST PORTAL LOBBY BUS TERMINAL SCIENCE CENTRE STATION: WHAT TO EXPECT Year What to Expect • Completion of all structural concrete works 2019 Milestones • Completion of support of excavation • Completion of excavation • Interior works at Station Box • Interior and exterior finishes as Main Entrance • Track work and rail installation Remaining Work • Waterproofing and backfill for 2020 • Permanent road restoration • Substantial completion late 2020 SCIENCE CENTRE STATION PROGRESS PHOTOS WALL TILING AT THE MAIN ENTRANCE GLAZING AT THE BUS TERMINAL Aga Khan & Museum Stop to O’Connor Stop (Don Valley Parkway to Victoria Park Ave) Brentcliffe Portal AGA KHAN PARK & MUSEUM STOP RENDERINGS SIDEWALK PLATFORM AERIAL VIEW WYNFORD STOP RENDERINGS SIDEWALK PLATFORM . -

Systems & Track: What to Expect

IT’S HAPPENING, TODAY Forum Eglinton Crosstown LRT Metrolinx’s Core Business – Providing Better, Faster, Easier Service We have a strong connection with our Adding More Service Today Making It Easier for Our customers, and a Customers to Access Our great understanding Service of who they are and Building More to Improve Service where they are going. Planning for New Connections Investing in Our Future MISSION: VISION: WE CONNECT GETTING YOU THERE COMMUNITIES BETTER, FASTER, EASIER 3 WELCOME Our Central Open House will feature the following stations: • Forest Hill • Chaplin • Avenue (Eglinton Connects) • Eglinton • Mount Pleasant Station • Leaside PROJECT QUANTITIES 273.5 km 111 escalators 15.2 million job hours medium voltage/ 38 two-vehicle trains direct current cable 208 overhead 60 elevators 6000 tons of rail 5 new bridges catenary system poles 60 KM/H street level MODEL: Bombardier Flexity Freedom POWER SUPPLY: Overhead Catenary Read more about how Eglinton Crosstown will change Toronto’s cityscape here. Train Testing Video: Click Here Eglinton Crosstown PROJECT UPDATE • The Eglinton Crosstown project is now over 75% complete • Three stations – Mount Dennis, Keelesdale and Science Centre – are largely complete • Over 85% of track has been installed • 45 LRVs have arrived at the EMSF to date • Vehicle testing is now underway Eglinton Crosstown What to Expect: Systems & Track 2020 Progress to-date Remaining Work in 2020 Remaining Work for 2021 • Track installed between Mount Dennis Station • Track installation between Wynford Stop to -

Area 83 Eastern Ontario International Area Committee Minutes June 2

ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AREA 83 EASTERN ONTARIO INTERNATIONAL Area 83 Eastern Ontario International Area Committee Minutes June 2, 2018 ACM – June 2, 2018 1 ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AREA 83 EASTERN ONTARIO INTERNATIONAL 1. OPENING…………………………………………………………………………….…………….…4 2. REVIEW AND ACCEPTANCE OF AGENDA………………………………….…………….…...7 3. ROLL CALL………………………………………………………………………….……………….7 4. REVIEW AND ACCEPTANCE OF MINUTES OF September 9, 2017 ACM…………………7 5. DISTRICT COMMITTEE MEMBERS’ REPORTS ……………………………………………....8 District 02 Malton……………………………………………………………………………….…….. 8 District 06 Mississauga……………………………………………………………………….…….. 8 District 10 Toronto South Central…………………………………………………………….….…. 8 District 12 Toronto South West………………………………………………………………….…. 9 District 14 Toronto North Central………………………………………………………………..….. 9 District 16 Distrito Hispano de Toronto…………………………………………………….………..9 District 18 Toronto City East……………………………………………………………………........9 District 22 Scarborough……………………………………………………………………………… 9 District 26 Lakeshore West………………………………………………………………….……….10 District 28 Lakeshore East……………………………………………………………………………11 District 30 Quinte West…………………………………………………………………………….. 11 District 34 Quinte East……………………………………………………………………………… 12 District 36 Kingston & the Islands……………………………………………………………….… 12 District 42 St. Lawrence International………………………………………………………………. 12 District 48 Seaway Valley North……………………………………………………………….……. 13 District 50 Cornwall…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 District 54 Ottawa Rideau……………………………………………………………………………. 13 District 58 Ottawa Bytown…………………………………………………………………………… -

Toronto Subway System, ON

Canadian Geotechnical Society Canadian Geotechnical Achievements 2017 Toronto Subway System Geotechnical Investigation and Design of Tunnels Geographical location Key References Wong, JW. 1981. Geotechnical/ Toronto, Ontario geological aspects of the Toronto subway system. Toronto Transit Commission. When it began or was completed Walters, DL, Main, A, Palmer, S, Construction began in 1949 and continues today. Westland, J, and Bihendi, H. 2011. Managing subsurface risk for Toronto- York Spadina Subway extension project. Why a Canadian geotechnical achievement? 2011 Pan-Am and CGS Geotechnical Conference. Construction of the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) subway system, the first in Canada, began in 1949 and currently consists Photograph and Map of four subway lines. In total there are currently approximately 68 km of subway tracks and 69 stations. Over one million trips are taken daily on the TTC during weekdays. The subway system has been expanded in several stages, from 1954, when the first line (the Yonge Line) was opened, to 2002, when the most recently completed line (the Sheppard Line) was opened. Currently the Toronto-York Spadina Subway Extension is under construction. The subway tunnels have been constructed using a number of different technologies over the years including: open cut excavation, open/closed shield tunneling under ambient air pressure and compressed air, hand mining and earth pressurized tunnel boring machines. The subway tunnels range in design from reinforced concrete box structures to approximately 6 m diameter precast concrete segmental liners or cast iron segmental liners. Looking east inside newly constructed TTC subway The tunnels have been advanced through various geological tunnel, 1968. (City of Toronto Archives) formations: from hard glacial tills to saturated alluvial sands and silts, and from glaciolacustrine clays to shale bedrock. -

Building Community Wealth Through Real Estate Investment

Building Community Wealth through Real Estate Investment Technical Assistance Panel Report | December 2020 1 Table of Contents 1. Background and Context ........................................................................................................................... 3 2. The Assignment......................................................................................................................................... 4 3. The TAP .................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Day One: Overview of Models ................................................................................................................... 5 5. Day 2: Overview of discussions ................................................................................................................. 8 6. Next Steps ............................................................................................................................................ 11 Appendix A: The Team ................................................................................................................................ 12 Appendix B: About the Urban Land Institute................................................................................................ 13 2 1. Background and Context Toronto’s soaring real estate market and affordability challenges are well-documented. These challenges are particularly pressing for renters: since the mid-1970s, little in the way -

MINISTRY of CORRECTIONS Facilities AREA 83

MINISTRY OF CORRECTIONS Facilities AREA 83 Name of Facility Address Contact Numbers Area / District Brockville Jail 613-341-2870 10 Wall St. Fax: 613-342-0962 Area 83 Brockville, ON K6V 4R9 District 66 Golden Triangle Ontario 905-457-7050 109 McLaughlin Rd. S. Correctional Institute Fax: 905-452-8606 Area 83 Brampton, ON L6Y 2C8 District 02 Malton St. Lawrence Valley 613-341-2870 Area 83 PO Box 8000 1804 Hwy 2 Correctional & Fax: 613-345-3844 E. Treatment Centre District 66 Golden Triangle Brockville, ON K6V 7N2 Central East 705-328-6000 Area 83 Correctional Centre 541 Hwy 36 Fax: 705-328-6001 Lindsay, ON K9V 6H2 District 86 Kawartha Quinte 613-354-9701 89 Richmond Blvd. Area 83 Detention Centre Fax: 613-354-1209 Napanee, ON K7R 3S1 District 34 Quinte East Ottawa-Carleton Detention 613-824-6080 Area 83 Centre 2244 Innes Road Fax: 613-824-0732 Ottawa, ON K1B 4C4 District 54 Ottawa Rideau Toronto South Detention Center 160 Horner Ave. Area 83 Etobicoke, Ont District 6/18 Toronto Intermittent Centre 160 Horner Ave. (TIC) Etobicoke, Ont Toronto East 416-750-3513 Area 83 55 Civic Rd. Detention Centre Fax: 416-750-3345 Toronto (Scarborough), District 22 Scarborough ON M1L 2K9 1 of 1 FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL FACILITIES AREA 83 ONTARIO REGION Institutions Regional Treatment Centre (Max) Millhaven Institution (Max) 560 King Street West Highway 33 PO Box 22 PO Box 280 Kingston, Ontario K7L 4V7 Bath, Ontario K0H 1G0 (613) 536-6901 (613) 351-8000 Fax: (613) 536-4115 Fax: (613) 351-8136 A/Executive Director: Kathy Hinch Warden: Curtis Jackson District -

High-End Ground Floor Showroom/Office with Castlefield Ave Exposure

For Lease 1184 Castlefield Avenue North York, ON High-end ground floor showroom/office with Castlefield Ave exposure Get more information Tom Clancy Tessa Compagno Broker, Principal Sales Representative, Associate +1 905 283 2388 +1 905 283 2342 [email protected] [email protected] Showroom/Office 1184 Castlefield Avenue Available For Lease North York, ON CASTLEFIELD AVENUE FAIRBANK AVENUE MIRANDA AVENUE ROSELAWN AVENUE Property Overview Highlights – Recently renovated retail/showroom/office space Total Area 7,500 sf located in the heart of the Design District – Entire ground floor available with prime exposure on Office Area 90% to busy Castlefield Avenue – Prime opportunity for upscale retailers, designers, and Industrial Area 10% traditional office users – Dedicated truck level door and shared access to drive Clear Height 13’ in door 1 Truck level door – Exposed wood ceiling deck, polished concrete floors Shipping 1 Drive-in door and upgraded lighting – Plenty of large windows throughout providing tons of Asking Net Rate $30.00 psf natural light – Private washroom and kitchenette within the space T.M.I. $5.50 psf – Reserved parking is available Possession 120 days – Building brick recently painted and parking lot to be repaved and lines repainted Showroom/Office 1184 Castlefield Avenue Available For Lease North York, ON Photos Showroom/Office 1184 Castlefield Avenue Available For Lease North York, ON Toronto’s Design District DUFFERIN STREET 126 TYCOS DRIVE 117 TYCOS DRIVE 25 WINGOLD TYCOS DRIVE AVENUE 143 TYCOS DRIVE WINGOLD AVENUE 1184 CASTLEFIELD AVENUE 1330 CASTLEFIELD 95 RONALD AVENUE AVENUE CALEDONIA ROAD CASTLEFIELD AVENUE RONALD AVENUE 80 RONALD AVENUE 1381 CASTLEFIELD N AVENUE Toronto’s Design District is home to a mix of furniture showrooms, home and fashion designers and more. -

Graffiti Management Plan – Streetartoronto (Start) Partnership Programs 2015 Grant Allocation Recommendations

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Graffiti Management Plan – StreetARToronto (StART) Partnership Programs 2015 Grant Allocation Recommendations Date: March 24, 2015 To: Licensing and Standards Committee From: General Manager, Transportation Services Wards: All Reference p:\2015\ClusterB\tra\pr\ls15002pr Number: SUMMARY StreetARToronto (StART) is a partnership program launched in 2012 as a central feature of the City's Graffiti Management Plan. It is a proactive approach to both eliminating graffiti vandalism and supporting street art that adds character and visual interest to city streets. Initiated as part of the Community Partnership and Investment Program (CPIP), StART is administered by the Transportation Services, Public Realm Section, which is also responsible for coordinating and implementing all non-enforcement related components of the Graffiti Management Plan. StART engages and links residents, community groups, artists and arts organizations with each other as well as with City staff and Councillors. To expand the geographical reach of street art projects across the city, Public Realm staff conducted a broad outreach program including Information Session in all four districts. At the Information Sessions and in response to enquiries, StART staff encouraged potential applicants to develop projects for locations in wards where StART murals have not yet been installed. These priorities were also shown on the City's website. This report recommends funding for 19 mural projects to be delivered by community- based organizations under the 2015 StART Partnership Program including installations in five wards which currently do not have a StART Partnership mural. Staff are confident that mural installations will be recommended for all 44 wards within the city by 2016.