TTC SUBWAY MAP (AND HOW IT RUINS YOUR MOOD and MOVEMENT in the CITY) a Case Study and Redesign MPC MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geometric Distortion of Schematic Network Maps

Geometric distortion of schematic network maps Bernhard Jenny The London Underground map is one of the most popular maps of modern times, depicting the lines and stations of London’s rail system as a schematic diagram. Its present design is still very similar to Harry Beck’s original layout of 1933. The geometry is deliberately distorted to improve readability and facilitate way finding in the network. This short paper presents the visual results of a cartometric analysis of the current London Underground map. The analysis was carried out using MapAnalyst, a specialized program for computing distortion grids and other types of visualizations that illustrate the geometric accuracy and distortion of maps. The described method could help designers of schematic maps to verify their design against the “geometric truth”, and guide their choice among different design options. The London Underground map the globe, but also had an enduring influence on other areas of graphic information design. London Transport, of The famous London Underground map shows the Thames course, continues improving and extending the diagram and named metro stations with railway tracks as straight map, while still following Harry Beck’s initial design. line segments. Strictly speaking, it is not a map that aims at a metrically accurate depiction of the network, but it is Besides the ingenious layout of the railway lines at rather a diagram that accentuates the topological relations 45- and 90-degree angles, a purposeful enlargement of the of Underground stations. Henry “Harry” C. Beck produced central portion of the network is the main characteristic of the first sketch for the famous diagram in 1931. -

Toronto Subway System, ON

Canadian Geotechnical Society Canadian Geotechnical Achievements 2017 Toronto Subway System Geotechnical Investigation and Design of Tunnels Geographical location Key References Wong, JW. 1981. Geotechnical/ Toronto, Ontario geological aspects of the Toronto subway system. Toronto Transit Commission. When it began or was completed Walters, DL, Main, A, Palmer, S, Construction began in 1949 and continues today. Westland, J, and Bihendi, H. 2011. Managing subsurface risk for Toronto- York Spadina Subway extension project. Why a Canadian geotechnical achievement? 2011 Pan-Am and CGS Geotechnical Conference. Construction of the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) subway system, the first in Canada, began in 1949 and currently consists Photograph and Map of four subway lines. In total there are currently approximately 68 km of subway tracks and 69 stations. Over one million trips are taken daily on the TTC during weekdays. The subway system has been expanded in several stages, from 1954, when the first line (the Yonge Line) was opened, to 2002, when the most recently completed line (the Sheppard Line) was opened. Currently the Toronto-York Spadina Subway Extension is under construction. The subway tunnels have been constructed using a number of different technologies over the years including: open cut excavation, open/closed shield tunneling under ambient air pressure and compressed air, hand mining and earth pressurized tunnel boring machines. The subway tunnels range in design from reinforced concrete box structures to approximately 6 m diameter precast concrete segmental liners or cast iron segmental liners. Looking east inside newly constructed TTC subway The tunnels have been advanced through various geological tunnel, 1968. (City of Toronto Archives) formations: from hard glacial tills to saturated alluvial sands and silts, and from glaciolacustrine clays to shale bedrock. -

Rapid Transit in Toronto Levyrapidtransit.Ca TABLE of CONTENTS

The Neptis Foundation has collaborated with Edward J. Levy to publish this history of rapid transit proposals for the City of Toronto. Given Neptis’s focus on regional issues, we have supported Levy’s work because it demon- strates clearly that regional rapid transit cannot function eff ectively without a well-designed network at the core of the region. Toronto does not yet have such a network, as you will discover through the maps and historical photographs in this interactive web-book. We hope the material will contribute to ongoing debates on the need to create such a network. This web-book would not been produced without the vital eff orts of Philippa Campsie and Brent Gilliard, who have worked with Mr. Levy over two years to organize, edit, and present the volumes of text and illustrations. 1 Rapid Transit in Toronto levyrapidtransit.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 About this Book 9 Edward J. Levy 11 A Note from the Neptis Foundation 13 Author’s Note 16 Author’s Guiding Principle: The Need for a Network 18 Executive Summary 24 PART ONE: EARLY PLANNING FOR RAPID TRANSIT 1909 – 1945 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNING OF RAPID TRANSIT PLANNING IN TORONTO 25 1.0 Summary 26 1.1 The Story Begins 29 1.2 The First Subway Proposal 32 1.3 The Jacobs & Davies Report: Prescient but Premature 34 1.4 Putting the Proposal in Context CHAPTER 2: “The Rapid Transit System of the Future” and a Look Ahead, 1911 – 1913 36 2.0 Summary 37 2.1 The Evolving Vision, 1911 40 2.2 The Arnold Report: The Subway Alternative, 1912 44 2.3 Crossing the Valley CHAPTER 3: R.C. -

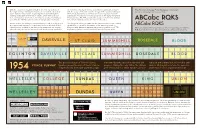

TTC Typography History

With the exception of Eglinton Station, 11 of the 12 stations of The intention of using Helvetica and Univers is unknown, however The Toronto Subway Font (Designer Unknown) the original Yonge Subway line have been renovated extensively. with the usage of the latter on the design of the Spadina Subway in Based on Futura by Paul Renner (1928) Some stations retained the original typefaces but with tighter 1978, it may have been an internal decision to try and assimilate tracking and subtle differences in weight, while other stations subsequent renovations of existing stations in the aging Yonge and were renovated so poorly there no longer is a sense of simplicity University lines. The TTC avoided the usage of the Toronto Subway seen with the 1954 designs in terms of typographical harmony. font on new subway stations for over two decades. ABCabc RQKS Queen Station, for example, used Helvetica (LT Std 75 Bold) in such The Sheppard Subway in 2002 saw the return of the Toronto Subway an irresponsible manner; it is repulsively inconsistent with all the typeface as it is used for the names of the stations posted on ABCabc RQKS other stations, and due to the renovators preserving the original platfrom level. Helvetica became the primary typeface for all TTC There are subtle differences between the two typefaces, notably the glass tile trim, the font weight itself looks botched and unsuitable. wayfinding signages and informational material system-wide. R, Q, K, and S; most have different terminals, spines, and junctions. ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL BLOOR DANGER DA N GER Danger DO NOT ENTER Do Not Enter Do Not Enter DAVISVILLE ST CL AIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR EGLINTON DAVISVILLE ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR EGLINTON DAVISVILLE ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR The specially-designed Toronto Subway that embodied the spirit of modernism and replaced with a brutal mix of Helvetica and YONGE SUBWAY typeface graced the walls of the 12 stations, progress. -

Relief Line Update

Relief Line Update Mathieu Goetzke, Vice-President, Planning David Phalp, Manager, Rapid Transit Planning FEBRUARY 7, 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Relief Line South alignment identified by the City of Toronto as preferred, has a Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR) above 1.0, demonstrating the project’s value; however, since it is close to 1.0, it is highly sensitive to costs, so more detailed design work and procurement method choice will be of importance to maintain or improve this initial BCR. • Forecasts suggest that Relief Line South will attract ridership to unequivocally justify subway-level service; transit-oriented development opportunities can further boost ridership. • Transit network forecasts show that Relief Line South needs to be in operation before the Yonge North Subway Extension. Relief Line North provides further crowding relief for Line 1. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 2 SUBWAY EXPANSION - PROJECT STATUS Both Relief Line North and South and the Yonge North Subway Extension are priority projects included in the 2041 Regional Transportation Plan. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 3 RELIEF LINE SOUTH: Initial Business Case Alignments Evaluated • Metrolinx is developing an Initial Business Case on Relief Line South, evaluating six alignments according to the Metrolinx Business Case Guidance and the Auditor General’s 2018 recommendations • Toronto City Council approved the advancement of alignment “A” (Pape- Queen via Carlaw & Eastern) • Statement of Completion of the Transit Project Assessment Process (TPAP) received October 24, 2018. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 4 RELIEF -

Toronto Subway Air Quality Health Impact Assessment

Toronto Subway Air Quality Health Impact Assessment Prepared for: Toronto Public Health City of Toronto November 15, 2019 Toronto Subway Air Quality Health Impact Assessment Project Summary Introduction Toronto’s subway is a critical part of the Toronto Transit Commission’s (TTC) public transportation network. First opened in 1954, it spans over 77 km of track and 75 stations across the city. On an average weekday over 1,400,000 customer-trips are taken on the subway. In 2017, Health Canada reported levels of air pollution in the TTC subway system that were elevated compared with outdoor air. The Toronto Board of Health requested that Toronto Public Health (TPH) oversee an independent study to understand the potential health impacts of air quality issues for passengers in the Toronto subway system - The Toronto Subway Air Quality Health Impact Assessment (TSAQ HIA). The TSAQ HIA takes a holistic approach to assessing how subway use may positively and/or negatively impact the health and well-being of Torontonians. The HIA used a human health risk assessment (HHRA) approach to calculate the potential health risks from exposure to air pollutants in the subway, and the results of the HHRA were incorporated into the HIA. The TSAQ HIA sought to answer three overarching questions: 1. What is the potential health risk to current passengers from air pollutants in the subway system? 2. What are the potential health benefits to mitigation measures that could be implemented to improve air quality in the TTC subway system? 3. What is the overall impact of the TTC’s subway system on the health and well-being of Torontonians? Results of the Toronto Subway Air Qualty Health Impact Assessment The TSAQ HIA assessed the overall impact of subway use on the health and well-being of Torontonians. -

Tfl Corporate Archives

TfL Corporate Archives ‘MAPPING LONDON’ TfL C orporate Archives is part of Information Governance, General C ounsel TfL Corporate Archives The TfL Corporate Archives acts as the custodian of the corporate memory of TfL and its predecessors, with responsibility for collecting, conserving, maintaining and providing access to the historical archives of the organisation. These archives chart the development of the organisation and the decision making processes. The Archives provides advice and assistance to researchers from both within and outside of the business and seeks to promote the archive to as wide an audience as possible, while actively collecting both physical and digital material and adding personal stories to the archive. The Archives are part of Information Governance, within General Counsel. • “Mapping London” is intended as an introduction to the development and use of maps and mapping techniques by TfL and its predecessors. • The following pages highlight key documents arranged according to theme, as well as providing further brief information. These can be used as a starting point for further research if desired • This document is adapted from a guide that originally accompanied an internal exhibition Tube Map Development: Individual Companies • Prior to 1906, the individual railway companies produced their own maps and there was no combined map of the various lines. • The companies were effectively all in competition with each other and so the focus was steadfastly on the route of the individual line, where it went, and why it was of particular use to you. • Even when combined maps of a sort began to appear, following the establishment of the Underground Electric Railways Group, the emphasis often fell upon a particular line. -

Labyrinth Teacher Pack Part 1: Introduction Key Stages 1–5

Labyrinth Teacher Pack Part 1: Introduction Key Stages 1–5 Visit http://art.gov.uk/labyrinth/learning to download Part 2: Classroom Activities, Cover Lessons & Resources 1 Foreword This two-part resource, produced in partnership with A New Direction, has been devised for primary- and secondary-school teachers, with particular relevance to those in reach of the Tube, as an introduction to Labyrinth, a project commissioned from artist Mark Wallinger by Art on the Underground to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the London Tube. The aim is to inform and inspire teachers about this Visit http://art.gov.uk/labyrinth/learning to special project, for which Wallinger has designed a download the Teacher Pack, Part 2: Classroom unique artwork, each bearing a labyrinth design, for Activities, Cover Lesson & Resources This pack all 270 stations on the Tube network. We hope that contains a variety of classroom-activity suggestions the resource will promote knowledge and for different subjects that can be used as a springboard enthusiasm that will then be imparted to the children for teachers to devise their own projects. Key stage and their families throughout the capital and beyond, suggestions are given, although many of these and will encourage them to explore the Underground activities can be adapted for a variety of year groups, network on an exciting hunt for labyrinths. depending upon the ability of the students involved. This Teacher Pack, Part 1 of the resource, provides Details are also given about the Labyrinth Schools introductory information about the project Labyrinth Poster Competition, the winners of which will have and gives background details about the artist. -

Mathematical Aspects of Public Transportation Networks

Mathematical Aspects of Public Transportation Networks Niels Lindner July 9, 2018 July 9, 2018 1 / 48 Reminder Dates I July 12: no tutorial (excursion) I July 16: evaluation of Problem Set 10 and Test Exam I July 19: no tutorial I July 19/20: block seminar on shortest paths I August 7 (Tuesday): 1st exam I October 8 (Monday): 2nd exam Exams I location: ZIB seminar room I start time: 10.00am I duration: 60 minutes I permitted aids: one A4 sheet with notes July 9, 2018 2 / 48 Chapter 6 Metro Map Drawing x6.1 Metro Maps July 9, 2018 3 / 48 x6.1 Metro Maps Berlin, 1921 (Pharus-Plan) alt-berlin.info July 9, 2018 4 / 48 x6.1 Metro Maps Berlin, 1913 (Hochbahngesellschaft) Sammlung Mauruszat, u-bahn-archiv.de July 9, 2018 5 / 48 x6.1 Metro Maps Berlin, 1933 (BVG) Sammlung Mauruszat, u-bahn-archiv.de July 9, 2018 6 / 48 x6.1 Metro Maps London, 1926 (London Underground) commons.wikimedia.org July 9, 2018 7 / 48 x6.1 Metro Maps London, 1933 (Harry Beck) July 9, 2018 8 / 48 x6.1 Metro Maps Plaque at Finchley Central station Nick Cooper, commons.wikimedia.org July 9, 2018 9 / 48 x6.1 Metro Maps Berlin, 1968 (BVG-West) Sammlung Mauruszat, u-bahn-archiv.de July 9, 2018 10 / 48 x6.1 Metro Maps Berlin, 2018 (BVG) Wittenberge RE6 RB55 Kremmen Stralsund/Rostock RE5 RB12 Templin Stadt Groß Schönebeck (Schorfheide) RB27 Stralsund/Schwedt (Oder) RE3 RE66 Szczecin (Stettin) RB24 Eberswalde Legende Barrierefrei durch Berlin Key to symbols Step-free access Sachsenhausen (Nordb) RB27 Schmachtenhagen 7 6 S-Bahn-/U-Bahn : Aufzug Oranienburg 1 RB20 : Wandlitzsee -

Beck to the Future: Time to Leave It Alone

ICC2013 Dresden Beck to the Future: time to leave it alone William Cartwright1 and Kenneth Field2 1Geospatial Science, RMIT University, Melbourne Victoria 3001, Australia 2Esri Inc, 380 New York Street, Redlands, CA 92373-8100, USA Abstract When one thinks of a map depicting London, generally the image that appears is of that of the map designed by Beck. It has become a design icon. Beck’s map, designed in 1933, and first made available to London commuters in 1933, has become the image of the geography of London and, generally, the mental map that defines how London ‘works’. As a communication tool, Beck’s map does work. It is an effective communicator of the London Underground train network and the distribution of stations and connections between one line and others. Whilst it is acknowledged that the geography of London is distorted, it still retains the status of ‘the’ map of London. The paper asserts that Beck’s map is over-used. It has suffered years of abuse and that has diluted its own place in cartographic history. The first component of the paper begins by providing a brief background of Beck and his London Underground map. This is followed by an outline of the three principle ways in which Beck’s ideas have been used. It then considers if, as previously stated, this map is a design icon or classic design. This is followed by a review of the attributes that appear to make it cartographically functional. Once these elements have been established the paper further reviews how, even if the geography is depicted in a way that distorts the true geography of London, users really don’t care, and they consume the map as a tool for moving about London, underground. -

Beck's Representation of London's Underground System: Map Or Diagram?

GSR_2 RMIT University, Melbourne December, 2012 Beck's representation of London's Underground system: map or diagram? William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences, RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Prior to 1932, maps provided by London Transport clung closely to the geography above ground, irrespective of the fact that the system being represented was a different geography altogether. In 1931, Electrical Draughtsman, Harry Beck designed a completely new representation of the Underground, which ignored the geography aboveground and concentrated on ‘mapping’ the lines, stations and interchanges. His design was tested by London Transport in 1932, with a trial print run. It was an immediate success! By distorting geography Beck made the product more usable and an effective communicator about how to move about (under) London. Quite recently, many from the design community have questioned whether Beck’s representation of London’s underground rail system is a map or a diagram. The majority of articles on this topic come from the design community, and they generally support the view that Beck’s product is a diagram, rather than a map. Very little comment on this debate comes from the cartographic community. This paper considers, from a cartographic perspective, whether Beck’s representation of the London Underground is in fact a map. It provides the results of a survey, which canvassed the international cartography and design community about whether Beck's representation is a ‘map’ or a 'diagram'. The contribution is unashamedly made from the viewpoint of a cartographer. However, the analysis has been made in a rigorous and unbiased manner. -

Applying Life Cycle Assessment to Analyze the Environmental Sustainability of Public Transit Modes for the City of Toronto

Applying life cycle assessment to analyze the environmental sustainability of public transit modes for the City of Toronto by Ashton Ruby Taylor A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography & Planning in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2016 Copyright © Ashton Ruby Taylor, 2016 Abstract One challenge related to transit planning is selecting the appropriate mode: bus, light rail transit (LRT), regional express rail (RER), or subway. This project uses data from life cycle assessment to develop a tool to measure energy requirements for different modes of transit, on a per passenger-kilometer basis. For each of the four transit modes listed, a range of energy requirements associated with different vehicle models and manufacturers was developed. The tool demonstrated that there are distinct ranges where specific transit modes are the best choice. Diesel buses are the clear best choice from 7-51 passengers, LRTs make the most sense from 201-427 passengers, and subways are the best choice above 918 passengers. There are a number of other passenger loading ranges where more than one transit mode makes sense; in particular, LRT and RER represent very energy-efficient options for ridership ranging from 200 to 900 passengers. The tool developed in the thesis was used to analyze the Bloor-Danforth subway line in Toronto using estimated ridership for weekday morning peak hours. It was found that ridership across the line is for the most part actually insufficient to justify subways over LRTs or RER. This suggests that extensions to the existing Bloor-Danforth line should consider LRT options, which could service the passenger loads at the ends of the line with far greater energy efficiency.