Researchspace@Auckland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Pacific Islands

A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS I. C. Campbell A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Thi s One l N8FG-03S-LXLD A History of the Pacific Islands I. C. CAMPBELL University of California Press Berkeley • Los Angeles Copyrighted material © 1989 I. C. Campbell Published in 1989 in the United States of America by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles All rights reserved. Apart from any fair use for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, no part whatsoever may by reproduced by any process without the express written permission of the author and the University of California Press. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Campbell, LC. (Ian C), 1947- A history of the Pacific Islands / LC. Campbell, p. cm. "First published in 1989 by the University of Canterbury Press, Christchurch, New Zealand" — T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-520-06900-5 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-520-06901-3 (pbk. alk. paper) 1. Oceania — History. I. Title DU28.3.C35 1990 990 — dc20 89-5235 CIP Typographic design: The Caxton Press, Christchurch, New Zealand Cover design: Max Hailstone Cartographer: Tony Shatford Printed by: Kyodo-Shing Loong Singapore C opy righted m ateri al 1 CONTENTS List of Maps 6 List of Tables 6 A Note on Orthography and Pronunciation 7 Preface. 1 Chapter One: The Original Inhabitants 13 Chapter Two: Austronesian Colonization 28 Chapter Three: Polynesia: the Age of European Discovery 40 Chapter Four: Polynesia: Trade and Social Change 57 Chapter Five: Polynesia: Missionaries and Kingdoms -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

Forecast 1954

. UTRIGGER CAN0E CLUB JUNE FORECAST 1954 ‘'It’s Kamehameha Day—Come Buy a Lei" (This is a scene we hope will never disappear in Hawaii.) flairaii Visitors Bureau Pic SEE PAGE 5 — ENTERTAINMENT CALENDAR Fora longer smoother ride... Enjoy summer’s coolest drink. G I V I AND Quinac The quickest way to cool contentment in a glass . Gin-and-Quinac. Just put IV2 ounces of gin in a tall glass. Plenty of ice. Thin slice of P. S. Hnjoy Q u in a c as a delicious beverage. Serve lemon or lime. Fill with it by itself in a glass with Quinac . and you have an lots of ice and a slice of easy to take, deliciously dry, lemon or lime. delightfully different drink. CANADA DRY BOTTLING CO. (HAWAII) LTD. [2] OUTRIGGER CANOE CLUB V o l. 13 N o. « Founded 190S WAIKIKI BEACH HONOLULU, HAWAII OFFICERS SAMUEL M. FULLER...............................................President H. VINCENT DANFORD............................ Vice-President MARTIN ANDERSON............................................Secretary H. BRYAN RENWICK..........................................Treasurer OIECASI DIRECTORS Issued by the Martin Andersen Leslie A. Hicks LeRoy C. Bush Henry P. Judd BOARD OF DIRECTORS H. Vincent Danford Duke P. Kahanamoku William Ewing H. Bryan Renwlck E. W. STENBERG.....................Editor Samuel M. Fuller Fred Steere Bus. Phone S-7911 Res. Phone 99-7664 W illard D. Godbold Herbert M. Taylor W. FRED KANE, Advertising.............Phone 9*4806 W. FREDERICK KANE.......................... General Manager CHARLES HEEf Adm in. Ass't COMMITTEES FINANCE—Samuel Fuller, Chairman. Members: Les CASTLE SW IM -A. E. Minvlelle, Jr., Chairman. lie Hicks, Wilford Godbold, H. V. Danford, Her bert M. -

Creating Equitable South- North Partnerships: Nurturing the Vā and Voyaging the Audacious Ocean Together

CREATING EQUITABLE SOUTH- NORTH PARTNERSHIPS: NURTURING THE VĀ AND VOYAGING THE AUDACIOUS OCEAN TOGETHER A Case Study in the Oceanic Pacific ‘Ofa-Ki-Levuka Louise Guttenbeil-Likiliki 35 women leaders from the Global South OCTOBER 2020 courageously share their perspectives of engagement with Global North organisations 1990-2020 2 we sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood Teaiwa (2008) 3 CREATING EQUITABLE SOUTH-NORTH PARTNERSHIPS: NURTURING THE VĀ AND VOYAGING THE AUDACIOUS OCEAN TOGETHER This report was written by ‘Ofa-Ki-Levuka Guttenbeil-Likiliki. Artwork concept and illustrations by IVI Designs. Design and layout by Gregory Ravoi. Copyright © IWDA 2020. ‘Ofa-Ki-Levuka Guttenbeil-Likiliki, the artists and IWDA give permission for excerpts from the report to be used and reproduced provided that the author, artists and source are properly and clearly acknowledged. Suggested citation: Guttenbeil-Likiliki, ‘Ofa-Ki-Levuka (2020), Creating Equitable South-North Partnerships: Nurturing the Vā and Voyaging the Audacious Ocean Together, Melbourne: IWDA. ISBN: 978-0-6450082-0-3 4 A CASE STUDY IN THE OCEANIC PACIFIC TABLE OF CONTENTS Greeting from the author 7 Executive Summary 10 Introduction 18 Key Findings 24 Recommendations 54 Conclusion 58 References 60 Annexes: 1. Guidance Literature Review 64 2. Talanoa Research Methodology: Decolonizing Knowledge 72 3. Focus on Three Organisations and One Regional Network 76 4. Participant Information and Consent Form 86 5. Research Guiding Questions 89 Each section of this report commences with a quote from conversations with Oceanic researchers, academics, feminists, activists and research participants. Each quote represents a wave of Oceania in its diversity and audacity. -

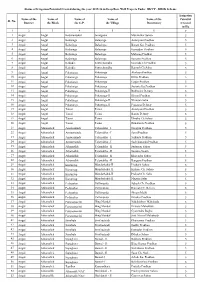

Sl. No. Name of the District Name of the Block Name of the G.P. Name Of

Status of Irrigation Potential Created during the year 2015-16 in Deep Bore Well Projects Under BKVY - DBSK Scheme Irrigation Name of the Name of Name of Name of Name of the Potential Sl. No. District the Block the G.P. the Village Beneficiary Created in Ha. 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Angul Angul Badakantakul Jamugadia Muralidhar Sahoo 5 2 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Antaryami Pradhan 5 3 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Basant Ku. Pradhan 5 4 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Kumudini Pradhan 5 5 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Maharag Pradhan 5 6 Angul Angul Balasinga Balasinga Santanu Pradhan 5 7 Angul Angul Kakudia Santarabandha Govinda Ch.Pradhan 5 8 Angul Angul Kakudia Santarabandha Ramesh Ch.Sahu 5 9 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga Akshaya Pradhan 5 10 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga Dillip Pradhan 5 11 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga Gagan Pradhan 5 12 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga Susanta Ku.Pradhan 5 13 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga-II Budhadev Dehury 5 14 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga-II Khirod Pradhan 5 15 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga-II Niranjan Sahu 5 16 Angul Angul Pokatunga Pokatunga-II Prasanna Dehury 5 17 Angul Angul Tainsi Tainsi Antaryami Pradhan 5 18 Angul Angul Tainsi Tainsi Banita Dehury 5 19 Angul Angul Tainsi Tainsi Dhruba Ch.Sahoo 5 20 Angul Angul Tainsi Tainsi Runakanta Pradhan 5 21 Angul Athamalick Amsarmunda Talamaliha - I Narayan Pradhan 5 22 Angul Athamalick Amsarmunda Talamaliha - I Saroj Pradhan 5 23 Angul Athamalick Amsarmunda Talamaliha - I Srikanta Pradhan 5 24 Angul Athamalick Amsarmunda Talamaliha - I Sachidananda Pradhan 5 25 Angul Athamalick Athamallik Talamaliha - II Sudarsan Sahoo 5 26 Angul Athamalick Athamallik Talamaliha - II Susanta Swain 5 27 Angul Athamalick Athamallik Talamaliha - II Khirendra Sahoo 5 28 Angul Athamalick Athamallik Talamaliha - II Banguru Pradhan 5 29 Angul Athamalick Kurumtap Mandarbahal-II Pitabash Sahoo 5 30 Angul Athamalick Kurumtap Mandarbahal-II Kishore Ch. -

Street Name Street# Range Pickup Day(S)

County of Maui - Refuse Pickup Days (Maui Island-Central, Upcountry, West, South) Street name Street# Range Pickup Day(s) Pickup Method AA PL TueFri Automated AA ST TueFri Automated AALA PL MonThu Automated AE PL Mon Manual AEA PL TueFri Automated AELOA RD Thu Manual AEWA PL MonThu Automated AHAAINA WAY MonThu Automated AHAIKI ST MonThu Automated AHEAHE PL MonThu Automated AHINA PL MonThu Automated AHINAHINA PL TueFri Automated AHOLO RD MonThu Automated AHONUI PL Fri Manual AHUALANI PL MonThu Automated AHULUA PL Wed Manual AHUWALE PL MonThu Automated AI ST Tue Manual AIA PL Fri Manual AIAI ST MonThu Automated AIKANE PL Mon Manual AILANA PL MonThu Automated AINA LANI DR MonThu Automated AINA MANU PL Tue Manual AINA PL MonThu Automated AINAHOU PL Mon Manual AINAKEA PL TueFri Automated AINAKEA RD 41 - 1431 TueFri Automated AINAKEA RD 1486 - 1684 TueFri Automated AINAKULA RD TueFri Automated AINAOLA ST Mon Manual W AIPUNI PL 2 - 45 TueFri Automated E AIPUNI PL 156 - 162 TueFri Automated AIPUNI ST 48 - 155 TueFri Automated AKAAKA ST Thu Manual AKAHAI PL Mon Manual AKAHELE ST TueFri Automated AKAI ST MonThu Automated AKAIKI PL TueFri Automated AKAKE ST MonThu Automated AKAKUU ST MonThu Automated AKALA DR TueFri Automated AKALANI LP MonThu Automated AKALEI PL MonThu Automated AKEA PL TueFri Automated AKEKE PL TueFri Automated Page 1 of 35 County of Maui - Refuse Pickup Days (Maui Island-Central, Upcountry, West, South) Street name Street# Range Pickup Day(s) Pickup Method AKEU PL TueFri Automated AKI ST Wed Manual AKINA ST MonThu Automated AKOA -

Primary Urban Center Development Plan Area

i)EvEIoPMENT PLANS PRIMARY URBAN CENTER DEVELOPMENT PLAN Exhibit A4, May 2004 Department of Planning and Permitting City and County of Honolulu Jeremy Harris, Mayor City Clerk, Eff. Date: 6-21-04 \. 24-23 ( k)I1OI1I Iii S[I1p. 5. 8—04) . a . I)[:vFL,opMENr PLx’cs PUC DE\E:LoP\IENT PL.N TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 24-29 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 24-30.2 THE ROLE OF THE PRIMARY URBAN CENTER IN OAHU’S DEVELOPMENT PATTERN 24-30.8 2. THE VISION FOR THE PUC’S FUTIJRF 24-30.10 2.1 Honolulu’s Natural, Cultural and Scenic Resources are Protected and Enhanced 24-30.10 2.2 Livable Neighborhoods Have Business Districts, Parks and Plazas, and Walkable Streets 24-30.10 2.3 The PUC Offers In-Town Housing Choices for People of All Ages and Incomes 24-30.12 2.4 Honolulu is the Pacific’s Leading City and Travel Destination 24-30.12 2.5 A Balanced Transportation System Provides Mobility 24-30.14 3. LAND USE AND TRANSPORTATION 24-30.15 3.1 Protecting and Enhancing Natural, Cultural, and Scenic Resources 24-30.15 3.1.1 Existing Conditions, Issues and Trends 24-30.15 3.1.2 Policies 24-30.23 3.1.3 Guidelines 24-30.23 24-30.26 3.1 .4 Relation to Views and Open Space Map (A. I and A.2) 3.2 Neighborhood Planning and Improvement 24-30.26 3.2.! Existing Conditions. Issues and Trends 24-30.27 3.2.2 Policies 24-30.33 3.2.3 Relation to Land Use Maps (A.4-A.6) and Zoning 24-30.36 3.3 In-Town Housing Choices 24-30.39 3.3.1 Existing (‘onditions. -

Information to Users

The political ecology of a Tongan village Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Stevens, Charles John, 1950- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 00:11:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290684 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper lefr-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

The Union and Journal: Vol. 17, No. 51

gflfllt & fob f rmthi0[ or AU. K1HM. »cca At it romiro itvbt rauur bob* PiapUiti, Town Rtporti, School BT L #. COWU EDITOR 1311) PBOMCTOI. Posters and HandbllU for Thoatroo. Oon- Office- Jlrick 11 look. llooper'a o«rU, Ao., Waddinc Carda. Vlaitin# Carda, BoilnM Carda, Duetotlla, TKKMX — Two Dallas* Pbb WW-hOm Uviubii* Pirrr Cr*.,irp«t«l w*U«t«3 ■oath* Blank Btempta, Bank Chaoka, r»«<u Um ol MbMrtbiBf. mm*!* i wuu. tinO ZjabaU of ntry da*orlptlon, XA> K A4t«rtWaf Union aurano* (TRKMH)r«DVRRTI!IINO-lHMrr«r PoUelN, Forwardln* Oarda, 0«b or Iwrtl"®*) • • |l-®> tqaBW 1»«i,(3 • wlikli I over the Mind or 3 ioMrtloiu. |1| rack we«li alWr. Die. BUlaof In Col* ■ TCRMMt rru^-M. H>>0 J It**. Lading, Ao., to., iBMrtMO. • • • • • • fl "Eternal to piloted 1Mb SUlMMJUtBt 3 ■miIm frrnrnt ilwftfMkwrikliit. I Hostility every form of Oppression Body+of Man"~-Jej[crsonx oraor with Bronaa,—airoutad attblaOffloo A squar* la IJ lin»« .Noop*r»U tvp*. Rpeetal XotlfM not w*«k—«li IIbm or leu, $0 WITH 1BITIBM AND DltfATM, Hnlti ri«M«tii>K lis line*, t or 11U • lln«. And on tha Y*»rlr •J*Brt»»»r« will t*«har<v<l IliiU, (papar EDITOR A5D IK HOOPER'S BRICK. LIBERTY STREET, moat Bnaaonabla Tanna. 1 PROPRIETOR.—OFFICE BLOCK, IboIm'Ic*! «im1 1iiu.i<m1 lu «»rrmir» <>m> r.1) LOUIS 0. COWAN, Kj»»r«. wMkly, «te*M W> b* jr*M for la pn.p..rtl..r .No uutK« Uku of uuiyflwil •uBiuauiOAtiuo* grpaaaaa mFwimw miMMLr aa. -

Midpacific Volume41 Issue5.Pdf

Vol. XLI. No. 5 25 Cent s a Copy May, 1931 MID-PACIFIC MAGAZINE, lion. Dn.ight F. Davis, Governor-General of the Philippines. ggyeoac -4.- -fa;I niirauconT a nom-, Arni yuyulcvlii----vii---vrT-iirnfi , • • •Vestrirm •• 1 • • •• 4. I 1 Tlirr filth -tlarttir Maga3ittr CONDUCTED BY ALEXANDER HUME FORD I Volume XLI Number 5 • CONTENTS FOR MAY, 1931 • Art Section—Food Crops in Pacific Lands r■ 402 4, Hon. Dwight F. Davis, Governor-General of the 4,. Philippine Islands 417 i By Cayetano Ligot • Development of Travel on the Pacific 418 • By James King Steele 1 Hawaii as It Relates to the Travel Industry - - - 421 I i By Harry N. Burhans VI Russia and Beyond 423 By Hireschi Saito The Director of the Pan-Pacific Union Visits Tokyo - - 427 Fire Walkers in Fiji 429 1. By Keith E. Cullum 4 • iT Thhe Story of Port Arthur 431 By Clive Lord • The Turkestan-Siberian Railroad 434 1! . I Wonders of the Forbidden City 437 • f., By Hon. Wallace R. Farrington • 1 Modern Transportation in the Netherlands East Indies - - 440 . In Modern Korea 447 1 By Mary Dillingham Frear 4' Some Colonization Problems: A Canadian View - - - 451 • By Major E. J. Ashton .1 .1 The Development of Radio in Australia 457 .1 By E. T. Fisk t 4 The Canterbury Pilgrims in New Zealand 461 .1 42 By N. E. Goad • i In Japanese Toyland 465 • • By Alexander Hume Ford . A Bit About Siam 469 4 Celebes, the Vast and Little Known 475 P t By Marc T. Greene • • • General Economic Data on Mexico 479 -, P. -

Midpacific Volume24 Issue3.Pdf

VOL. XXIV. No. 3. 25 Cents a Copy. SEPTEMBER. 1922 011111111111111MME1111111111316111111111111111113MIMIIIII L .191e MID-PACIFIC MAGAZINE and the ra" BULLETIN OF THE PAN -PACIFIC UNION Hon. Yeh Kung Cho, Minister of Communications in China, and an officer of the Pan-Pacific Union. sIIIIIIIIIIIIIIiiat%r.11111111111111111Ca1teIIIIIIIIIIIl01L IIIIIIIIIIIInIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIC IIIIIIIIIIIIIIICaleIIIIIIIIIIIIIIne UNITED STATES AUSTRALASIA HAWAII ORIENT JAVA Am. News Co. Gordon & Gotch Pan-Pacific Union Kelly & Walsh Javasche Boekhandel ' • ' ' • ' • ' • ' ' ' •i ztlattlAttAtttatts.v Pan-Parifir Tinian Central Offices, Honolulu, Hawaii, at the Ocean's Crossroads. PRESIDENT, HON. WALLACE R. FARRINGTON, Governor of Hawaii. ALEXANDER HUME FORD, Director. DE. FRANK F. BUNKER, Executive Secretary and Treasurer The Pan-Pacific Union, representing the lands about the greatest of oceans, is partly supported by appropriations from Pacific governments. It works chiefly through the calling of conferences, for the greater advancement of, and cooperation among, all the races and peoples of the Pacific. HONORARY PRESIDENTS Warren G. Harding President of the United States William M. Hughes Prime Minister of Australia W. F. Massey Prime Minister of New Zealand Hsu Shih-Chang.... President of China Arthur Meighen Premier of Canada Prince I. Tokugawa President, House of Peers, Tokyo His Majesty, Rama VI King of Siam HONORARY VICE-PRESIDENTS Charles Evans Hughes Secretary of State, U. S. A. Woodrow Wilson Ex-President of United States Dr. L. S. Rowe Director-General Pan-American Union Yeh Rung Cho Minister of Communication, China Leonard Wood Governor-General of the Philippines The Governor-Generals of Alaska and Java. The Premiers of Australian States. John Oliver The Premier of British Columbia The Pan-Pacific Union is incorporated with an International Board of Trustees, representing races and nations of the Pacific. -

The Outrigger Story

The Outrigger Story Outrigger Waikiki on the Beach, 2012 I discovered an island™. I discovered Outrigger. A people steeped in tradition. Nurtured by the land. With gentle respect for the beauty that frames every day. I wasn’t the first to step onto its soil. But I feel I’ve found this island. At the heart of Outrigger Hotels & Resorts lies the spirit of discovery. For more than 60 years, we have shared a warm island welcome with our guests: today we strive to also bring them meaningful experiences; ones that will touch their hearts and create lifetime memories. Welcome to Outrigger. The Outrigger Story In 2012, Outrigger Enterprises Group celebrates 65 years of hospitality. What is today a top multi-branded, multi-faceted hotel management company in the Asia-Pacific region began as the dream of Roy C. Kelley, who pioneered the concept of family-style hotel rooms in Waikiki. Together with his wife, Estelle, he helped bring the dream of a vacation in paradise within the reach of the everyday traveler. In so doing, he forever changed the face of Hawaii’s visitor industry. Boulevard, Montegue Hall at Punahou School, the old The Kelley Family Halekulani Hotel, and the former Waikiki Theater. Entrepreneurs at heart, in 1932 the Kelleys went into part-time business for themselves by constructing a six-room apartment building in Waikiki. Other apartment buildings soon followed. During this time, however, the only hotels available to visitors in Waikiki were the Royal Hawaiian, the Halekulani and the Moana – all catering to the wealthy and well to do.