Appendix 3 REGIONAL CENTERS of the KLEZMORIM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Działalność Polityczno-Wojskowa Chorążego Koronnego I Wojewody Kijowskiego Andrzeja Potockiego W Latach 1667–1673*

143 WSCHODNI ROCZNIK HUMANISTYCZNY TOM XVI (2019), No 2 s. 143-167 doi: 10.36121/zhundert.16.2019.2.143 Zbigniew Hundert (Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum) ORCID 0000-0002-5088-2465 Działalność polityczno-wojskowa chorążego koronnego i wojewody kijowskiego Andrzeja Potockiego w latach 1667–1673* Streszczenie: Andrzej Potocki był najstarszym synem wojewody krakowskiego i hetmana wielkiego koronnego Stanisława „Rewery”. Związany był ze swoją rodzimą ziemią halicką, w której zaczynał karierę wojskową, jako rotmistrz jazdy w 1648 r., oraz karierę polityczną. Od 1646 r. był starosta sądowym w Haliczu, co wpływało na jego polityczną pozycję w regionie oraz nakładało na niego obowiązek zapewnienia pogranicznej ziemi halickiej bezpieczeństwa. W latach 1647–1668, jako poseł, aż 15 razy reprezentował swoją ziemię na sejmach walnych. W 1667 r. był już doświadczonym pułkownikiem wojsk koronnych. Posiadał kilka jednostek wojskowych w ramach koronnej armii zaciężnej oraz blisko tysiąc wojsk nadwornych na potrzeby obrony pogranicza. Po śmierci ojca w 1667 r. faktycznie stał się głową rodu Potockich. Związany był już wtedy politycznie z dworem Jana Kazimierza i z osobą marszałka wielkiego i hetmana polnego – a od 1668 r. wielkiego koronnego Jana Sobieskiego. W związku z tym jeszcze w 1665 r. otrzymał urząd chorążego koronnego. W 1667 r. bezskutecznie starał się też o buławę polną w przypadku awansu Sobieskiego na hetmaństwo wielkie. Potem brał udział w kampanii podhajeckiej, dowodząc grupą wojsk koronnych, swoich nadwornych i pospolitego ruszenia. W 1668 r. wszedł do senatu w randze wojewody kijowskiego, próbując oddziaływać na życie polityczne Kijowszczyzny i angażować się w sprawę odzyskania z rąk rosyjskich Kijowa. W okresie panowania Michała Korybuta (1669–1673) był jednym z najbardziej aktywnych liderów opozycji i jednym z najbliższych współpracowników politycznych i wojskowych Sobieskiego. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2012, No.27-28

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: l Guilty verdict for killer of abusive police chief – page 3 l Ukrainian Journalists of North America meet – page 4 l A preview: Soyuzivka’s Ukrainian Cultural Festival – page 5 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXX No. 27-28 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JULY 1-JULY 8, 2012 $1/$2 in Ukraine Ukraine at Euro 2012: Yushchenko announces plans for new political party Another near miss by Zenon Zawada Special to The Ukrainian Weekly and Sheva’s next move KYIV – Former Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko was known for repeatedly saying that he hates politics, cre- by Ihor N. Stelmach ating the impression that he was doing it for a higher cause in spite of its dirtier moments. SOUTH WINSOR, Conn. – Ukrainian soccer fans Yet even at his political nadir, Mr. Yushchenko still can’t got that sinking feeling all over again when the game seem to tear away from what he hates so much. At a June 26 officials ruled Marko Devic’s shot against England did not cross the goal line. The goal would have press conference, he announced that he is launching a new evened their final Euro 2012 Group D match at 1-1 political party to compete in the October 28 parliamentary and possibly inspired a comeback win for the co- elections, defying polls that indicate it has no chance to qualify. hosts, resulting in a quarterfinal match versus Italy. “One thing burns my soul – looking at the political mosa- After all, it had happened before, when Andriy ic, it may happen that a Ukrainian national democratic party Shevchenko’s double header brought Ukraine back won’t emerge in Ukrainian politics for the first time in 20 from the seemingly dead to grab a come-from- years. -

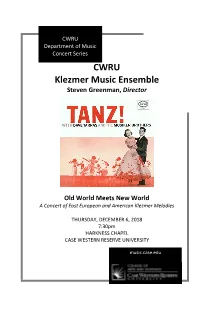

Klezmer Program 12.06.18

CWRU DepArtment oF MusIc Concert SerIes CWRU Klezmer Music Ensemble Steven Greenman, Director Old World Meets New World A Concert of East European and American Klezmer Melodies THURSDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2018 7:30pm HARKNESS CHAPEL CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY musIc.cAse.edu Welcome to Florence-Harkness Memorial Chapel RESTROOMS Women’s And men’s restrooms Are locAted on the mAIn level oF the buildIng. PAGERS, CELL PHONES, COMPUTERS, IPADS AND LISTENING DEVICES As A courtesy to the perFormers And AttendIng AudIence members, pleAse power oFF All electronic And mechanicAl devIces, Including pagers, cellulAr telephones, computers IPAds, wrIst wAtch AlArms, etc. prIor to the stArt oF the concert. PHOTOGRAPHY, VIDEO AND RECORDING DEVICES As A courtesy to the perFormers And AudIence members, photogrAphy And vIdeogrAphy Is strIctly prohibIted durIng the perFormAnce. FACILITY GUIDELINES In order to preserve the beAuty And cleAnlIness oF the hAll, no Food or beverAge, Including wAter, Is permItted. A DrInkIng FountAIn Is locAted neAr the restrooms beside the classroom. IN THE EVENT OF AN EMERGENCY ContAct An usher or A member oF the house stAFF IF you requIre medIcAl AssIstAnce. Emergency exIts Are cleArly marked throughout the buIldIng. Ushers And house staFF wIll provIde Instruction In the event oF An emergency. musIc.cAse.edu/FAcIlItIes/Florence-harkness-memorIAl-chApel/ Program “Rumania” Bulgar AlexAnder OlshAnetsky -from the recordIng Tanz! With Dave Tarras and the Musiker Brothers - 1955 Chused’l #10 from International HeBrew Wedding Music (“HAsIdIc DAnce #10) by W. KostAkowsky - 1916 Dem Trisker Rebn’s Khosid TrAdItIonAl/DAve TArrAs (“The TrIsker Rebbe’s DAnce”) Recorded - 1925 Yiddish Bulgar Max EpsteIn (“JewIsh BulgAr”) Recorded wIth the HymIe JAcobson OrchestrA - 1947 Romanian Fantasy Pt. -

Polish Battles and Campaigns in 13Th–19Th Centuries

POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 Scientific editors: Ph. D. Grzegorz Jasiński, Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Reviewers: Ph. D. hab. Marek Dutkiewicz, Ph. D. hab. Halina Łach Scientific Council: Prof. Piotr Matusak – chairman Prof. Tadeusz Panecki – vice-chairman Prof. Adam Dobroński Ph. D. Janusz Gmitruk Prof. Danuta Kisielewicz Prof. Antoni Komorowski Col. Prof. Dariusz S. Kozerawski Prof. Mirosław Nagielski Prof. Zbigniew Pilarczyk Ph. D. hab. Dariusz Radziwiłłowicz Prof. Waldemar Rezmer Ph. D. hab. Aleksandra Skrabacz Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Prof. Lech Wyszczelski Sketch maps: Jan Rutkowski Design and layout: Janusz Świnarski Front cover: Battle against Theutonic Knights, XVI century drawing from Marcin Bielski’s Kronika Polski Translation: Summalinguæ © Copyright by Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita, 2016 © Copyright by Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości, 2016 ISBN 978-83-65409-12-6 Publisher: Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości Contents 7 Introduction Karol Olejnik 9 The Mongol Invasion of Poland in 1241 and the battle of Legnica Karol Olejnik 17 ‘The Great War’ of 1409–1410 and the Battle of Grunwald Zbigniew Grabowski 29 The Battle of Ukmergė, the 1st of September 1435 Marek Plewczyński 41 The -

Klezmer Dances

Klezmer Dances Alexandrovsky Valts (all around the circle of fifths, Mazel Tov Mekhutonim (congratulations for the in-law trad., Arr. WU), tutti, 1st performance 9.2.10 people, rather slow, Abe Schwartz, transcr. Jacobs) (2:39) [Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, Chicago. Publ. Araber tants (Naftule Brandwein 1889-1963, arr. WU, Tara Music] extremely polyphonic), soloist Daniëlle de Jong, sopra- no sax; five clarinets, 1st performance 11.5.12 Moritzpolka (trad. Polish-Jewish, arr. WU), soloist Mo- ritz Brößler, bass clarinet / clarinet, Anke Saeger, Bulgar-Trilogy (trad., Arr. WU, unfinished), tutti Tenor sax, tutti, 3:30, 1st performance 9.11.14 Varshaver freylekhs (trad., arr. WU), soloist Claudia Oy tate / Ot azoy (Lt. Joseph Frankel‘s Orchestra 1919 Schumann, clarinet / Der heyser bulgar (the hot B., / Shloimke Beckerman and Abe Schwartz Orchestra Naftule Brandwein, Arr. WU), soloist Carsten Fette, 1923, arr. WU – two pieces during which the band sang clarinet, 1st performances 11.3.12 / 9.11.14 unexpectedly…), soloists Katharina Müller and Sabine Freylakhs-Trilogy (three dances with temperament, Pelzer, soprano recorders; tutti, 1st perf. 28.4.13 (3:51) trad., Arr. WU), tutti (4:00) Patsh Tantz (trad., arr. KlezPO), tutti, 1st perf. 10.11.09 Freylekhs fun der khupe (dance under the wedding Serba din New York (Romaneasca Orch. = Abe canopee, Kandel‘s Orchestra ca. 1920, transcr. Koff- Schwartz‘s Orchestra, transcr. Jacobs, arr. Juri Bo- man) / Kolomeike (dance from the West Ukraine, kov) / Ruski Sher (trad., arr. Yoelin) / Lebedik un trad., arr. Margolis), solo Howard Schultens, banjo freylekh (Abe Schwartz, arr. Juri Bokov / Koffman) (4:36) [Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, Chicago. -

To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Marissa Gogan Thesis Submitted to the Faculty Of

To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Marissa Gogan Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History David P. Cline, Co-Chair Brett L. Shadle, Co-Chair Rachel B. Gross 4 May 2016 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Identity, Klezmer, Jewish, 20th Century, Folk Revival Copyright 2016 by Claire M. Gogan To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Gogan ABSTRACT Klezmer, a type of Eastern European Jewish secular music brought to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century, originally functioned as accompaniment to Jewish wedding ritual celebrations. In the late 1970s, a group of primarily Jewish musicians sought inspiration for a renewal of this early 20th century American klezmer by mining 78 rpm records for influence, and also by seeking out living klezmer musicians as mentors. Why did a group of Jewish musicians in the 1970s through 1990s want to connect with artists and recordings from the early 20th century in order to “revive” this music? What did the music “do” for them and how did it contribute to their senses of both individual and collective identity? How did these musicians perceive the relationship between klezmer, Jewish culture, and Jewish religion? Finally, how was the genesis for the klezmer revival related to the social and cultural climate of its time? I argue that Jewish folk musicians revived klezmer music in the 1970s as a manifestation of both an existential search for authenticity, carrying over from the 1960s counterculture, and a manifestation of a 1970s trend toward ethnic cultural revival. -

Regional Social and Cultural Benefits of The

Aleksandra Ćwik POLISHING THE PEARL: REGIONAL SOCIAL AND CULTURAL BENEFITS OF THE REVITALIZATION OF THE POTOCKI PALACE IN RADZYŃ PODLASKI, POLAND MA Thesis in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Central European University Budapest May 2018 CEU eTD Collection POLISHING THE PEARL: REGIONAL SOCIAL AND CULTURAL BENEFITS OF THE REVITALIZATION OF THE POTOCKI PALACE IN RADZYŃ PODLASKI, POLAND by Aleksandra Ćwik (Poland) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2018 POLISHING THE PEARL: REGIONAL SOCIAL AND CULTURAL BENEFITS OF THE REVITALIZATION OF THE POTOCKI PALACE IN RADZYŃ PODLASKI, POLAND by Aleksandra Ćwik (Poland) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader Budapest May 2018 CEU eTD Collection -

Klezmer Music, History, and Memory 1St Edition Ebook Free Download

KLEZMER MUSIC, HISTORY, AND MEMORY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Zev Feldman | 9780190244514 | | | | | Klezmer Music, History, and Memory 1st edition PDF Book Its primary venue was the multi-day Jewish wedding, with its many ritual and processional melodies, its table music for listening, and its varied forms of Jewish dance. The second part of the collection examines the klezmer "revival" that began in the s. Krakow is not far from Auschwitz and each year, a March of the Living, which takes visitors on a walk from Auschwitz to the nearby Birkenau death camp, draws tens of thousands of participants. Its organizers did not shy from the topic. But, I continued, we don't celebrate the military victory. Some aspects of these Klezmer- feeling Cohen compositions, as rendered, were surely modern in some of the instruments used, but the distinctive Jewish Klezmer feel shines through, and arguably, these numbers by Cohen are the most widely-heard examples of Klezmer music in the modern era due to Cohen's prolific multi-generational appeal and status as a popular poet-songwriter-singer who was very popular on several continents in the Western World from the s until his death in Ornstein, the director of the Jewish Community Center, said that while the festival celebrates the past, he wants to help restore Jewish life to the city today. All About Jazz needs your support Donate. Until this can be accessed, Feldman's detailed study will remain the go-to work for anyone wishing to understand or explore this endlessly suggestive subject. With Chanukah now past, and the solstice just slipped, I am running out of time to post some thoughts about the holiday. -

The Internationally Acclaimed Festival of Yiddish/Jewish Culture and the Arts KLEZKANADA

The Internationally Acclaimed Festival of Yiddish/Jewish Culture and the Arts KLEZKANADA August 22- 28, 2011 Founders From the KlezKanada Board of Directors Hy and Sandy Goldman Again we are so privileged to welcome you (and welcome you back) to KlezKanada on behalf of the Board, our faculty and artistic staff. As we arrive at Camp B’nai Brith, we marvel when our Artistic Coordinator, Summer Festival gem of Jewish culture comes alive, in its sounds, songs, language, dance and performance. It Frank London binds us as a community committed to connect, not to a lost past, but to a living present. We are grounded in our contact with our treasured giants, such as Flory Jagoda and Theodore Bikel, and Artistic Coordinator, Local Programming and Montreal Jewish Music Festival nourished and realized in the work of our faculty who created the renaissance and the generation Jason Rosenblatt of younger leaders who carry it to new places. Our pride, our nakhes, knows no limit when we see artists who came of age in our scholarship and fellowship programs, now take the world Founding Artistic Director and Senior Artistic Advisor stage. Jeff Warschauer We are also extremely gratified that KlezKanada has now linked up with the McGill University Board of Directors Schulich School of Music through the Department of Jewish Studies and will be hosting a group of McGill students for the week. This sets a precedent and augers well for future academic Bob Blacksberg, Stan Cytrynbaum (legal consultant), Tzipie Freedman (secretary), Hy associations. Goldman (chair), Sandra Goldman (registrar), Adriana Kotler, Robin Mader, Sandra Mintz, Bernard Rosenblatt, Roslyn Rosenblatt, Herschel Segal, David Sela, Robert Smolkin, Eric Now 16 years strong, we feel we have just begun. -

Folklife Festival Tjgjtm Smithsms Folklife Festival

Smithsonian Folklife Festival tjgJtm SmithsMS Folklife Festival On the National Mall Washington, D.C. June 24-28 & July 1-5 Cosponsored by the National Park Service 19 98 SMITHSONIAN ^ On the Cover General Festival LEFT Hardanger fiddle made by Ron Poast of Black Information 101 Earth, Wisconsin. Photo © Jim Wildeman Services & Hours BELOW, LEFT Participants Amber, Baltic Gold. Photo by Antanas Sutl(us Daily Schedules BELOW, CENTER Pmi lace Contributors & Sponsors from the Philippines. Staff Photo by Ernesto Caballero, courtesy Cultural Special Concerts & Events Center of the Philippines Educational Offerings BELOW, RIGHT Friends of the Festival Dried peppers from the Snnithsonian Folkways Recordings Rio Grande/ Rio Bravo Basin. Photo by Kenn Shrader Contents ^ I.Michael Heyman 2 Inside Front Cover The festival: On the Mall and Back Home Bruce Babbitt Cebu Islanders process as part of the Santo Nino (Holy 3 Child) celebrations in Manila, the Philippines, in 1997. Celebrating Our Cultural Heritage Photo by Richard Kennedy Diana Parker 4 Table of Contents Image Jhe festival As Community .^^hb The Petroglyph National Monument, on the outskirts Richard Kurin 5 ofAlbuquerque, New Mexico, is a culturally significant Jhe festival and folkways — space for many and a sacred site for Pueblo peoples. Ralph Rinzler's Living Cultural Archives Photo by Charlie Weber Jffc Site Map on the Back Cover i FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL Wisconsin Pahiyas: The Rio Grande/ Richard March 10 A Philippine Harvest Rio Bravo Basin Wisconsin Folldife Marian Pastor Roces 38 Lucy Bates, Olivia Cadaval, 79 Robert T.Teske 14 Rethinking Categories: Heidi McKinnon, Diana Robertson, Cheeseheads, Tailgating, and the The Making of the ?di\\\yas and Cynthia Vidaurri Lambeau Leap: Tiie Green Bay Packers Culture and Environment in the Rio Richard Kennedy 41 and Wisconsin Folldife Grande/Rio Bravo Basin: A Preview Rethinking the Philippine Exhibit GinaGrumke 17 at the 1904 St. -

Drummer, Give Me My Sound: Frisner Augustin

Fall–Winter 2012 Volume 38: 3–4 The Journal of New York Folklore Drummer, Give Me My Sound: Frisner Augustin Andy Statman, National Heritage Fellow Dude Ranch Days in Warren County, NY Saranac Lake Winter Carnival The Making of the Adirondack Folk School From the Director The Schoharie Creek, had stood since 1855 as the longest single- From the Editor which has its origins span covered wooden bridge in the world. near Windham, NY, The Schoharie’s waters then accelerated to In the spirit of full dis- feeds the Gilboa Res- the rate of flow of Niagara Falls as its path closure, I’m the one who ervoir in Southern narrowed, uprooting houses and trees, be- asked his mom to share Schoharie County. fore bursting onto the Mohawk River, just her Gingerbread Cookie Its waters provide west of Schenectady to flood Rotterdam recipe and Christmas drinking water for Junction and the historic Stockade section story as guest contribu- New York City, turn of Schenectady. tor for our new Food- the electricity-generating turbines at the A year later, in October 2012, Hurricane ways column. And, why not? It’s really not New York Power Authority, and are then Sandy hit the metropolitan New York that we couldn’t find someone else [be in loosed again to meander up the Schoharie area, causing widespread flooding, wind, touch, if you’re interested!]. Rather, I think Valley to Schoharie Crossing, the site of and storm damage. Clean up from this it’s good practice and quite humbling to an Erie Canal Aqueduct, where the waters storm is taking place throughout the entire turn the cultural investigator glass upon of the Schoharie Creek enter the Mohawk Northeast Corridor of the United States oneself from time to time, and to partici- River. -

Naftule Brandwein, Dave Tarras and the Shifting Aesthetics in the Contemporary Klezmer Landscape

WHAT A JEW MEANS IN THIS TIME: Naftule Brandwein, Dave Tarras and the shifting aesthetics in the contemporary klezmer landscape Joel E. Rubin University of Virginia Clarinetists Naftule Brandwein (1884-1963) and Dave Tarras (1895-1989) were the two leading performers of Jewish instrumental klezmer music in New York during the first half of the 20th century. Due to their virtuosity, colorful personalities and substantial recorded legacy, it was the repertoire and style of these two musicians that served as the major influence on the American (and transnational) klezmer revival movement from its emergence in the mid-1970s at least until the mid-1990s.1 Naftule Brandwein playing a solo in a New York catering hall, ca. late 1930s. Photo courtesy of Dorothea Goldys-Bass 1 Dave Tarras playing a solo in a New York catering hall, ca. early 1940s. Photo courtesy of the Center for Traditional Music and Dance, New York. Since that time, the influence of Brandwein and Tarras on contemporary klezmer has waned to some extent as a younger generation of klezmer musicians, many born in the 1970s and 1980s, has adopted new role models and the hegemony of the Brandwein-Tarras canon has been challenged.2 In particular, beginning in the early 1990s and continuing to the present, a parallel interest has developed among many contemporary klezmer musicians in the eastern European roots of the tradition. At the same time, a tendency towards innovation and a fusing of traditional klezmer music of various historical periods and regions with a variety of styles has emerged. These include jazz, rhythm and blues, funk, Hip-Hop and Balkan music.