The Cases of Ła ´Ncut and Włodawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland—An Outline

The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland ♦ 1 The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland—an Outline Michał Galas Jagiellonian University In the historiography of Judaism in the Polish lands the influence of Reform Judaism is often overlooked. he opinion is frequently cited that the Polish Jews were tied to tradition and did not accept ideas of religious reform coming from the West. his paper fills the gap in historiography by giving some examples of activities of progressive communities and their leaders. It focuses mainly on eminent rabbis and preachers such as Abraham Goldschmidt, Markus Jastrow, and Izaak Cylkow. Supporters of progressive Judaism in Poland did not have as strong a position as representatives of the Reform or Conservative Judaism in Germany or the United States. Religious reforms introduced by them were for a number of reasons moderate or limited. However, one cannot ignore this move- ment in the history of Judaism in Poland, since that trend was significant for the history of Jews in Poland and Polish-Jewish relations. In the historiography of Judaism in the Polish lands, the history of the influ- ence of Reform Judaism is often overlooked. he opinion is frequently cited that the Polish Jews were tied to tradition and did not accept ideas of religious reform coming from the West. his opinion is perhaps correct in terms of the number of “progressive” Jews, often so-called proponents of reform, on Polish soil, in comparison to the total number of Polish Jews. However, the influence of “progressives” went much further and deeper, in both the Jewish and Polish community. -

Arquitectas Polacas Del S.XX Y Su Huella En La Ciudad De Varsovia

Arquitectas polacas del S.XX y su huella en la ciudad de Varsovia ALUMNA: Nuria Milvaques Casadó TUTORES: Eva Álvarez Isidro Carlos Gómez TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO Grado en Fundamentos de la Arquitectura Universitat Politécnica de Valencia Escuela Superior de Arquitectura de Valencia Septiembre 2019 Arquitectas polacas del S.XX y su huella en la ciudad de Varsovia Nuria Milvaques Casadó “Reconocer nuestra propia invisibilidad significa encontrar por fin el camino hacia la visibilidad” Mitsuye Yamada 3 · RESUMEN Y PALABRAS CLAVE Con este trabajo, pretendo dar visibilidad a algunas arquitectas y a sus obras, creando una guía de proyectos hechos por mujeres polacas en la ciudad de Varsovia. Esta ciudad fue una de las más destruidas durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Se han necesitado muchos años para reconstruirla. Se necesitaron, y se siguen necesitando muchos profesionales para llevar a cabo todos los proyectos, tanto de reconstrucción como de obra nueva. Entre todos estos profesionales hay muchas mujeres, que a lo largo de todo el Siglo XX han participado en la reurbanización de esta gran capital. Muchas de ellas fueron fundadoras o formaron parte de grandes grupos de diseño y arquitectura, diseñando distritos completos y trabajando en la Oficina de Reconstrucción de Varsovia. El objetivo final del trabajo es crear un blog abierto donde poder recoger más información que en este TFG no se haya podido abarcar. Palabras clave: Polonia; Varsovia; género; arquitectura; visibilidad · RESUM I PARAULES CLAU Amb aquest treball, pretenc donar visibilitat a algunes arquitectes i les seues obres, creant una guia de projectes fets per dones poloneses en la ciutat de Varsòvia. -

Q2 2019 Inside This Edition

Special Travel EditionQ2 2019 inside this edition... TRAVEL & LEISURE 04 William Burris’ Chinese Adventure BY WILLIAM BURRIS 20 Berkeley Burris’ Chinese Adventure BY BERKELEY BURRIS Special Travel Edition 38 BUSINESS PRACTICE A Quest for a 10 Pound Bonefish TRAVEL & LEISURE BY DR. LARRY SCARBOROUGH & DEVELOPMENT 41 61 84 Traveling to the Greek Islands Pro Travel Tips The Future Of An Orthodontist: BY DR. DANIELA LOEBL BY PROORTHO STAFF Closing The Loop On Virtual Treatments 45 64 BY NICK DUNCAN Russia in The Dead of Winter! Traveling to Europe 86 BY DR. BEN & BRIDGET BURRIS BY DR. BEN & BRIDGET BURRIS I Complained Loudly About the 49 70 AAO and This Happened Traveling to Peru Traveling to Spain BY DR. COURTNEY DUNN BY DR. DAVID WALKER BY DR. DAVID MAJERONI MARKETING/ 51 75 SOCIAL MEDIA Krakow: A Polish Jewel Croatia: Jewel of the Adriatic 89 BY DR. ANDREA FONT RYTZNER BY DR. PAYAM ZAMANI How to Compete with DIY Teeth-Straightening Companies by 57 78 Offering Teleorthodontic Services Traveling Through Brazil and Peru Family Fun in Europe Yourself BY DR. BEN & BRIDGET BURRIS BY DR. BEN & BRIDGET BURRIS BY DR. KEITH DRESSLER The ideas, views and opinions in each article are the opinion of the named author. They do not necessarily reflect the views Theof Progressive Orthodontist, its publisher, or editors. The Progressive Orthodontist® (“Publication”) DOES NOT provide any legal or accounting advice and the individuals reading this Publication should consult with their own lawyer for legal advice and accountant for accounting advice. The Publication is a general service that provides general information and may contain information of a legal or accounting nature. -

Zał. 5. P. Winskowski, Summary. Autoreferat

SUMMARY OF PROFESSIONAL ACCOMPLISHMENTS AUTOREFERAT W JĘZYKU ANGIELSKIM Załącznik nr 5 do wniosku o przeprowadzenie postępowania habilitacyjnego Piotr Winskowski Summary of Professional Accopmlishments Summary of Professional Accomplishments 1. First name and Surname Piotr Winskowski 2. Diplomas, certificates and academic degrees possessed – with application of names, places and years they were issued as well as title of doctoral dissertation 1. Master of Engineering (M.Sc. Eng.), graduated with distinction from the Faculty of Architecture of the Cracow University of Technology on December 11, 1992, based on the defence of the following thesis: A Student services centre and small theatre in Krakow. Advisor Prof. Witold Korski Eng. Arch. Diploma no. 3119/A. 2. PhD in technical sciences, academic degree conferred by resolution of the Council of the Faculty of Architecture, Cracow University of Technology on 1 July 1998 based on the defence of the following PhD dissertation: Technical inspirations in formal solutions employed in modern architecture Advisor: Prof. J. Tadeusz Gawłowski. PhD Eng. Arch. Diploma no. 1205. 3. Diploma awarded on completion of training course for academic teachers at the Centre for Pedagogy and Psychology, Cracow University of Technology, 1999. 3. Information regarding employment history in scientific/artistic institutions and organisations 1. Technical clerk, Independent Chair of Industrial Architecture Design, Faculty of Architecture, Cracow University of Technology, 21.01.1993‒30.11.1995. 2. Teaching-research -

Działalność Polityczno-Wojskowa Chorążego Koronnego I Wojewody Kijowskiego Andrzeja Potockiego W Latach 1667–1673*

143 WSCHODNI ROCZNIK HUMANISTYCZNY TOM XVI (2019), No 2 s. 143-167 doi: 10.36121/zhundert.16.2019.2.143 Zbigniew Hundert (Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum) ORCID 0000-0002-5088-2465 Działalność polityczno-wojskowa chorążego koronnego i wojewody kijowskiego Andrzeja Potockiego w latach 1667–1673* Streszczenie: Andrzej Potocki był najstarszym synem wojewody krakowskiego i hetmana wielkiego koronnego Stanisława „Rewery”. Związany był ze swoją rodzimą ziemią halicką, w której zaczynał karierę wojskową, jako rotmistrz jazdy w 1648 r., oraz karierę polityczną. Od 1646 r. był starosta sądowym w Haliczu, co wpływało na jego polityczną pozycję w regionie oraz nakładało na niego obowiązek zapewnienia pogranicznej ziemi halickiej bezpieczeństwa. W latach 1647–1668, jako poseł, aż 15 razy reprezentował swoją ziemię na sejmach walnych. W 1667 r. był już doświadczonym pułkownikiem wojsk koronnych. Posiadał kilka jednostek wojskowych w ramach koronnej armii zaciężnej oraz blisko tysiąc wojsk nadwornych na potrzeby obrony pogranicza. Po śmierci ojca w 1667 r. faktycznie stał się głową rodu Potockich. Związany był już wtedy politycznie z dworem Jana Kazimierza i z osobą marszałka wielkiego i hetmana polnego – a od 1668 r. wielkiego koronnego Jana Sobieskiego. W związku z tym jeszcze w 1665 r. otrzymał urząd chorążego koronnego. W 1667 r. bezskutecznie starał się też o buławę polną w przypadku awansu Sobieskiego na hetmaństwo wielkie. Potem brał udział w kampanii podhajeckiej, dowodząc grupą wojsk koronnych, swoich nadwornych i pospolitego ruszenia. W 1668 r. wszedł do senatu w randze wojewody kijowskiego, próbując oddziaływać na życie polityczne Kijowszczyzny i angażować się w sprawę odzyskania z rąk rosyjskich Kijowa. W okresie panowania Michała Korybuta (1669–1673) był jednym z najbardziej aktywnych liderów opozycji i jednym z najbliższych współpracowników politycznych i wojskowych Sobieskiego. -

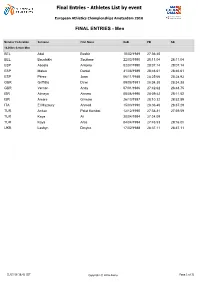

Final Entries - Athletes List by Event

Final Entries - Athletes List by event European Athletics Championships Amsterdam 2016 FINAL ENTRIES - Men Member Federation Surname First Name DoB PB SB 10,000m Senior Men BEL Abdi Bashir 10/02/1989 27:36.40 BEL Bouchikhi Soufiane 22/03/1990 28:11.04 28:11.04 ESP Abadía Antonio 02/07/1990 28:07.14 28:07.14 ESP Mateo Daniel 31/08/1989 28:46.61 28:46.61 ESP Pérez Juan 06/11/1988 28:25.66 28:28.93 GBR Griffiths Dewi 09/08/1991 28:34.38 28:34.38 GBR Vernon Andy 07/01/1986 27:42.62 28:48.75 ISR Almeya Aimeru 08/06/1990 28:09.42 28:11.52 ISR Amare Girmaw 26/10/1987 28:10.32 28:52.89 ITA El Mazoury Ahmed 15/03/1990 28:36.40 28:37.29 TUR $UÕNDQ Polat Kemboi 12/12/1990 27:38.81 27:59.59 TUR Kaya Ali 20/04/1994 27:24.09 TUR Kaya Aras 04/04/1994 27:48.53 29:16.0h UKR Lashyn Dmytro 17/02/1988 28:37.11 28:37.11 01/07/16 16:42 CET Copyright © 2016 Arena Page 1 of 32 Final Entries - Athletes List by event European Athletics Championships Amsterdam 2016 FINAL ENTRIES - Men Member Federation Surname First Name DoB PB SB 100m Senior Men AUT Fuchs Markus 14/11/1995 10.36 10.36 BUL Dimitrov Denis 10/02/1994 10.16 10.18 CZE Veleba Jan 06/12/1986 10.23 10.28 ESP Hortelano Bruno 18/09/1991 10.06 10.06 ESP Rodríguez Ángel David 25/04/1980 10.14 10.24 EST Niit Marek 09/08/1987 10.19 10.30 FRA Dutamby Stuart 24/04/1994 10.12 10.12 FRA Lemaitre Christophe 11/06/1990 9.92 10.09 FRA Vicaut Jimmy 27/02/1992 9.86 9.86 FRA Zeze Mickael-Meba 19/05/1994 10.21 10.21 GBR Edoburun Ojie 02/06/1996 10.16 10.19 GBR Ellington James 06/09/1985 10.11 10.11 GBR Gemili Adam 06/10/1993 -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2012, No.27-28

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: l Guilty verdict for killer of abusive police chief – page 3 l Ukrainian Journalists of North America meet – page 4 l A preview: Soyuzivka’s Ukrainian Cultural Festival – page 5 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXX No. 27-28 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JULY 1-JULY 8, 2012 $1/$2 in Ukraine Ukraine at Euro 2012: Yushchenko announces plans for new political party Another near miss by Zenon Zawada Special to The Ukrainian Weekly and Sheva’s next move KYIV – Former Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko was known for repeatedly saying that he hates politics, cre- by Ihor N. Stelmach ating the impression that he was doing it for a higher cause in spite of its dirtier moments. SOUTH WINSOR, Conn. – Ukrainian soccer fans Yet even at his political nadir, Mr. Yushchenko still can’t got that sinking feeling all over again when the game seem to tear away from what he hates so much. At a June 26 officials ruled Marko Devic’s shot against England did not cross the goal line. The goal would have press conference, he announced that he is launching a new evened their final Euro 2012 Group D match at 1-1 political party to compete in the October 28 parliamentary and possibly inspired a comeback win for the co- elections, defying polls that indicate it has no chance to qualify. hosts, resulting in a quarterfinal match versus Italy. “One thing burns my soul – looking at the political mosa- After all, it had happened before, when Andriy ic, it may happen that a Ukrainian national democratic party Shevchenko’s double header brought Ukraine back won’t emerge in Ukrainian politics for the first time in 20 from the seemingly dead to grab a come-from- years. -

Ebook As Diasporas Dos Judeus E Cristaos.Pdf

As Diásporas dos Judeus e Cristãos- -Novos de Origem Ibérica entre o Mar Mediterrâneo e o Oceano Atlântico. Estudos ORGANIZAÇÃO : José Alberto R. Silva Tavim Hugo Martins Ana Pereira Ferreira Ângela Sofia Benoliel Coutinho Miguel Andrade Lisboa Centro de História da Universidade de Lisboa 2020 Título As Diásporas dos Judeus e Cristãos-Novos de Origem Ibérica entre o Mar Mediterrâneo e o Oceano Atlântico. Estudos Organização José Alberto R. Silva Tavim, Hugo Martins, Ana Pereira Ferreira, Ângela Sofia Benoliel Coutinho e Miguel Andrade Revisão André Morgado Comissão científica Ana Isabel Lopez-Salazar Codes (U. Complutense de Madrid), Anat Falbel (U. Federal do Rio de Janeiro), Ângela Domingues (U. Lisboa), Beatriz Kushnir (Directora, Arq. Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro), Blanca de Lima (U. Francisco de Miranda, Coro; Acad. Nac. de la Historia-Capítulo Falcón, Venezuela), Claude B. Stuczynski (Bar-Ilan U.), Cynthia Michelle Seton-Rogers (U. of Texas-Dallas), Daniel Strum (U. São Paulo), Daniela Levy (U. São Paulo), Edite Alberto (Dep. Património Cultural/C. M. Lisboa; CHAM, FCSH-UNL), Elvira Azevedo Mea (U. Porto), Eugénia Rodrigues (U. Lisboa), Hernán Matzkevich (U. Purdue), Joelle Rachel Rouchou (Fund. Casa de Rui Barbosa, Rio de Janeiro), Jorun Poettering (Harvard U.), Maria Augusta Lima Cruz (ICS-U. do Minho; CHAM, FCSH, UNL), Maria Manuel Torrão (U. Lisboa), Moisés Orfali (Bar-Ilan U.), Nancy Rozenchan (U. de São Paulo), Palmira Fontes da Costa (U. Nova de Lisboa), Timothy D. Walker (U. Massachusetts Dartmouth) e Zelinda Cohen (Inst. do Património Cultural, Cabo Verde) Capa Belmonte, com Sinagoga Bet Eliahu. Fotografia de José Alberto R. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

The Preservation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Our

THE PRESERVATION OF AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU OUR RESPONSIBILITY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS ‘ THERE IS ONLY ONE THING WORSE THAN AUSCHWITZ ITSELF…AND THAT IS IF THE WORLD FORGETS THERE WAS SUCH A PLACE’ Henry Appel, Auschwitz survivor WŁADYSŁAW BARTOSZEWSKI’S APPEAL THE GENEration OF AUSCHWITZ survivors IS FADING away. We, former concentration camp prisoners and eyewitnesses of the Shoah, have devoted all our lives to the mission of keeping the memory of the Holocaust alive. Today, as our mission is coming to an end, we understand better than anyone else that our whole work and toil might be in vain if we do not succeed in bequeathing the material evidence of this terrible crime to future generations. The Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp remains the most important of these testimonies: once a place of suffering and death for hundreds of thousands of Jews, Poles, Roma, Sinti and people from all over Europe, today it is a memorial site visited by millions of people from around the world. Auschwitz-Birkenau Appeal 5 WŁADYSŁAW BARTOSZEWSKI’S APPEAL The Auschwitz camp buildings were hand built by us – the camp’s prisoners. I clearly recall that back Thus far, the entire financial burden of preserving the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Site has fallen on then none of us thought about how long they would last. Today, we are not the only ones that the Republic of Poland. Since the end of World War II, Poland has made a continuous effort to preserve understand that it is in that particular place that every man can fully grasp the enormity of this particular the remnants of Auschwitz and to collect and preserve countless testimonies and documents. -

Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation Master Plan for Preservation Report 2013 Foundation.Auschwitz.Org

Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation Master Plan for Preservation Report 2013 foundation.auschwitz.org 1 Contents INTRODUCTION 5 THE MISSION TO PRESERVE THE MEMORIAL 8 THE MASTER PLAN FOR PRESERVATION 12 PROJECTS COMPLETED IN 2013 16 PROJECTS CONTINUED IN 2013 20 PROJECTS INITIATED IN 2013 24 THE WORK OF THE AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU FOUNDATION IN 2013 30 THE AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU FOUNDATION 36 SUPPORT THE FOUNDATION 42 CONTACT 46 Interior of a brick barracks on the grounds of the women’s camp at the former Auschwitz II-Birkenau camp 2 OBJECTIVE Introduction photo: Mikołaj Grynberg Almost seventy years have passed since the liberation of Auschwitz. Not long from now, on January 27, 2015, we—the postwar generations—will stand together with the last Survivors. We will tell them that we have grown into Aour role, and that we understand what they have been trying to tell us all these years. The memory has ripened within us. We will also tell them—I hope—that just as their words will always remain a powerful warning, so also the tangible remains of the hell they lived through will bear eloquent witness for future generations. The authenticity of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial, the only one of the major extermination camps preserved to this degree, is systematically maintained today by professional conservators. To meet this challenge, 29 countries have decided to join in creating a Perpetual Capital of 120 million EUR. The revenue will finance comprehensive preservation work. Thanks to this, the authenticity of this place will endure to testify about the fate of those who can no longer tell their own story. -

Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/8027,The-IPN-paid-tribute-to-the-insurgents-from-the-Warsaw-Ghetto.html 2021-09-30, 23:04 19.04.2021 The IPN paid tribute to the insurgents from the Warsaw Ghetto The IPN paid tribute to the insurgents from the Warsaw Ghetto on the occasion of the 78th anniversary of the Uprising. The Deputy President of the Institute, Mateusz Szpytma Ph.D., and the Director of the IPN Archive, Marzena Kruk laid flowers in front of the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes in Warsaw on 19 April 2021. On 19 April 1943, fighters from the Jewish Fighting Organization (ŻOB) and the Jewish Military Union (ŻZW) mounted armed resistance against German troops who liquidated the ghetto. It was the last act of the tragedy of Warsaw Jews, mass-deported to Treblinka German death camp. The Uprising lasted less than a month, and its tragic epilogue was the blowing up of the Great Synagogue in Tłomackie Street by the Germans. It was then that SS general Jürgen Stroop, commanding the suppression of the Uprising, who authored the report documenting the course of fighting in the Ghetto (now in the resources of the Institute of National Remembrance) could proclaim that "the Jewish district in Warsaw no longer exists." On the 78th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Institute of National Remembrance would like to encourage everyone to learn more about the history of the uprising through numerous publications, articles and educational materials which are available on the Institute's website and the IPN’s History Point website: https://ipn.gov.pl/en https://przystanekhistoria.pl/pa2/tematy/english-content The IPN has been researching the history of the Holocaust and Polish- Jewish relations for many years.