The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland—An Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We All Know, the Emancipation Was a Great Turning Point in the History Of

PROGRESSIVE LITURGIES OF GERMANY AND AMERICA 585 p- John D. Rayner Introduction As we all know, the Emancipation was a great turning point in the history of Judaism, although ‘point' is hardly the right word, since it was a long-drawn- out process extending from the eighteenth century into the twentieth. Nevertheless the initial impact of it was often felt by a single generation, and in Germany by the generation of those born during the Napoleonic era. As we all know; too, the initial impact was for many of the newly emancipated German Jews a negative one so far as their Jewish religious life was concerned because the revolutionary educational, linguistic, cultural and social changes they experienced caused them to feel uncomfortable in the old- style synagogues. And as we all know as well, it is to this problem, of the alienation of emancipated Jewry from the traditional synagogue that the Reformers first and foremost addressed themselves. They believed that if only the synagogue services could be made more attractive, that would halt and perhaps reverse w the drift. 0 . _ {:1 j N In retrospect we can see that they were only partly right. There are other 8E}; factors besides the nature of synagogue worship which determine or influence the extent to which individuals will affirm their Jewish identity \ :8 " and adhere to their Jewish faith, and subsequent generations of Reformers 13E came to recognise that and to address themselves to these other issues also. (3 ‘1‘: Nevertheless the nature of synagogue worship is clearly a factor, and a big one. -

Geographischer Index

2 Gerhard-Mercator-Universität Duisburg FB 1 – Jüdische Studien DFG-Projekt "Rabbinat" Prof. Dr. Michael Brocke Carsten Wilke Geographischer und quellenkundlicher Index zur Geschichte der Rabbinate im deutschen Sprachgebiet 1780-1918 mit Beiträgen von Andreas Brämer Duisburg, im Juni 1999 3 Als Dokumente zur äußeren Organisation des Rabbinats besitzen wir aus den meisten deutschen Staaten des 19. Jahrhunderts weder statistische Aufstellungen noch ein zusammenhängendes offizielles Aktenkorpus, wie es für Frankreich etwa in den Archiven des Zentralkonsistoriums vorliegt; die For- schungslage stellt sich als ein fragmentarisches Mosaik von Lokalgeschichten dar. Es braucht nun nicht eigens betont zu werden, daß in Ermangelung einer auch nur ungefähren Vorstellung von Anzahl, geo- graphischer Verteilung und Rechtstatus der Rabbinate das historische Wissen schwerlich über isolierte Detailkenntnisse hinausgelangen kann. Für die im Rahmen des DFG-Projekts durchgeführten Studien erwies es sich deswegen als erforderlich, zur Rabbinatsgeschichte im umfassenden deutschen Kontext einen Index zu erstellen, der möglichst vielfältige Daten zu den folgenden Rubriken erfassen soll: 1. gesetzliche, administrative und organisatorische Rahmenbedingungen der rabbinischen Amts- ausübung in den Einzelstaaten, 2. Anzahl, Sitz und territoriale Zuständigkeit der Rabbinate unter Berücksichtigung der histori- schen Veränderungen, 3. Reihenfolge der jeweiligen Titulare mit Lebens- und Amtsdaten, 4. juristische und historische Sekundärliteratur, 5. erhaltenes Aktenmaterial -

Chief Rabbi Joseph Herman Hertz

A Bridge across the Tigris: Chief Rabbi Joseph Herman Hertz Our Rabbis tell us that on the death of Abaye the bridge across the Tigris collapsed. A bridge serves to unite opposite shores; and so Abaye had united the opposing groups and conflicting parties of his time. Likewise Dr. Hertz’s personality was the bridge which served to unite different communities and bodies in this country and the Dominions into one common Jewish loyalty. —Dayan Yechezkel Abramsky: Eulogy for Chief Rabbi Hertz.[1] I At his death in 1946, Joseph Herman Hertz was the most celebrated rabbi in the world. He had been Chief Rabbi of the British Empire for 33 years, author or editor of several successful books, and champion of Jewish causes national and international. Even today, his edition of the Pentateuch, known as the Hertz Chumash, can be found in most centrist Orthodox synagogues, though it is often now outnumbered by other editions. His remarkable career grew out of three factors: a unique personality and capabilities; a particular background and education; and extraordinary times. Hertz was no superman; he had plenty of flaws and failings, but he made a massive contribution to Judaism and the Jewish People. Above all, Dayan Abramsky was right. Hertz was a bridge, who showed that a combination of old and new, tradition and modernity, Torah and worldly wisdom could generate a vibrant, authentic and enduring Judaism. Hertz was born in Rubrin, in what is now Slovakia on September 25, 1872.[2] His father, Simon, had studied with Rabbi Esriel Hisldesheimer at his seminary at Eisenstadt and was a teacher and grammarian as well as a plum farmer. -

To Wear the Dust of War This Page Intentionally Left Blank to Wear the Dust of War

To Wear the Dust of War This page intentionally left blank To Wear the Dust of War From Bialystok to Shanghai to the Promised Land An Oral History by Samuel Iwry Edited by L. J. H. Kelley TO WEAR THE DUST OF WAR Copyright © Samuel Iwry, 2004. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2004 978-1-4039-6575-2 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published 2004 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin's Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-4039-6576-9 ISBN 978-1-4039-8120-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9781403981202 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Iwry, Samuel. To wear the dust of war : from Bialystok to Shanghai to the Promised Land : an oral history / by Samuel Iwry ; edited by L.J.H. Kelley. p. cm. -- (Palgrave studies in oral history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4039-6576-9 (pbk.) 1. Iwry, Samuel. 2. Jews--Poland--Biography. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939- 1945)--Poland--Personal narratives. 4. Refugees, Jewish--China--Shanghai- -Biography. -

Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/8027,The-IPN-paid-tribute-to-the-insurgents-from-the-Warsaw-Ghetto.html 2021-09-30, 23:04 19.04.2021 The IPN paid tribute to the insurgents from the Warsaw Ghetto The IPN paid tribute to the insurgents from the Warsaw Ghetto on the occasion of the 78th anniversary of the Uprising. The Deputy President of the Institute, Mateusz Szpytma Ph.D., and the Director of the IPN Archive, Marzena Kruk laid flowers in front of the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes in Warsaw on 19 April 2021. On 19 April 1943, fighters from the Jewish Fighting Organization (ŻOB) and the Jewish Military Union (ŻZW) mounted armed resistance against German troops who liquidated the ghetto. It was the last act of the tragedy of Warsaw Jews, mass-deported to Treblinka German death camp. The Uprising lasted less than a month, and its tragic epilogue was the blowing up of the Great Synagogue in Tłomackie Street by the Germans. It was then that SS general Jürgen Stroop, commanding the suppression of the Uprising, who authored the report documenting the course of fighting in the Ghetto (now in the resources of the Institute of National Remembrance) could proclaim that "the Jewish district in Warsaw no longer exists." On the 78th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Institute of National Remembrance would like to encourage everyone to learn more about the history of the uprising through numerous publications, articles and educational materials which are available on the Institute's website and the IPN’s History Point website: https://ipn.gov.pl/en https://przystanekhistoria.pl/pa2/tematy/english-content The IPN has been researching the history of the Holocaust and Polish- Jewish relations for many years. -

Coming to America…

Exploring Judaism’s Denominational Divide Coming to America… Rabbi Brett R. Isserow OLLI Winter 2020 A very brief early history of Jews in America • September 1654 a small group of Sephardic refugees arrived aboard the Ste. Catherine from Brazil and disembarked at New Amsterdam, part of the Dutch colony of New Netherland. • The Governor, Peter Stuyvesant, petitioned the Dutch West India Company for permission to expel them but for financial reasons they overruled him. • Soon other Jews from Amsterdam joined this small community. • After the British took over in 1664, more Jews arrived and by the beginning of the 1700’s had established the first synagogue in New York. • Officially named K.K. Shearith Israel, it soon became the hub of the community, and membership soon included a number of Ashkenazi Jews as well. • Lay leadership controlled the community with properly trained Rabbis only arriving in the 1840’s. • Communities proliferated throughout the colonies e.g. Savannah (1733), Charleston (1740’s), Philadelphia (1740’s), Newport (1750’s). • During the American Revolution the Jews, like everyone else, were split between those who were Loyalists (apparently a distinct minority) and those who supported independence. • There was a migration from places like Newport to Philadelphia and New York. • The Constitution etc. guaranteed Jewish freedom of worship but no specific “Jew Bill” was needed. • By the 1820’s there were about 3000-6000 Jews in America and although they were spread across the country New York and Charleston were the main centers. • In both of these, younger American born Jews pushed for revitalization and change, forming B’nai Jeshurun in New York and a splinter group in Charleston. -

The Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street

The Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street “There is no trace of Warsaw’s largest synagogue in The Bank Square. It was a symbol of Reform Judaism in the capital and one of the greatest Polish buildings built in the 19th century”. So says of the Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street Hanna Dzielińska (Hanka Warszawianka), journalist and tourist guide. The eighth episode of ‘Remnants of the Warsaw Ghetto’ also tells the story of the adjacent building of the Main Judaic Library, the Oneg Shabbat group operating next to it, and the largest project of its participants – the Ringelblum archive. ‘Remnants of the Warsaw Ghetto’ is a film series of 16 short guided tours presenting the history of places and people associated with them. The following places will be presented: Umschlagplatz; Anielewicz Mound; Szmul Zygielbojm Monument; Monument of the Ghetto Heroes; Grzybowski Square; Mariańska Street and the Nursing School; Nożyk Synagogue; Great Synagogue at Tłomackie Street; Nalewki Street; Femina Cinema Theater; Courts at Leszno Street; Chłodna Street; Waliców Street; The Jewish Cemetery at Okopowa Street, and the Bersohn and Bauman Hospital – the place where the permanent exhibition of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum will be created. The series presentation accompanies the commemoration of 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto borders closing, organized by the Warsaw Ghetto Museum in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and TSKŻ – the Social and Cultural Society of Jews in Poland. The main events took place on November 16, 2020. Publication date: 2021-08-19 Print date: 2021-09-18 11:46 Source: http://1943.pl/en/artykul/the-great-synagogue-on-tlomackie-street/. -

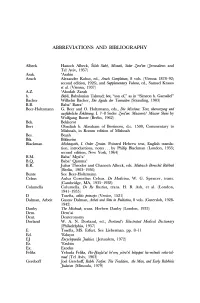

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

JEWISH STATISTICS the Statistics of Jews in the World Rests Largely Upon Estimates

306 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rests largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the numbers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. In spite of the unsatisfactor- iness of the method, it may be assumed that the numbers given are approximately correct. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1904, the English " Jewish Year Book" for 5664, the " Jewish Ency- clopedia," and the Alliance Israelite Universelle reports. Some of the statements rest upon the authority of competent individ- uals. A comparison with last year's statistics will show that for several countries the figures have been changed. In most of the cases, the change i6 due to the fact that the results of the census of 1900 and 1901 have only now become available. THE UNITED STATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the reli- gious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or naturalized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimate, though several of the estimates have been most conscientiously made. The Jewish population was estimated In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. -

Sfifficy1emooismel

.. ------.,~ SfiffiCy1emooIsmel NOVEMBER,2004/CHESHVAN-KISLEV,5765 What do Andrew & Lauren Amsterdam Randi-Ellen & Steven Lehrhoff Steve & Alison Auerbach Fred & Lizzy Leighton Jess & Amelia Berkowitz all these Scott & Nancy Levy Ronald & Judith Bickart Ibrahim Medawar & Carla Edelstein George & ~auren Blair wonderful Mark Mos'kbvitz & Marilyn Harris Robert & Diane Blumenfeld Igor & Elina Nachevnik Andrea & Daniel Cohen Andrew Nadel & Wendy Ferber Ronald & Joanne Doades people Nora Patrone Ron Fastov & Laurie Levine Staci Pereira Jeffrey & Katherine Feld Bruce & Arianna Pleat Evan & Sherri Fischer have in Lance & Margaret Podell Stephen & Joanne Fisher Douglas & Susan Present Elaine Gaidemak Paula Radding Scott & Nina Gallin common RhodaRaff Craig & Pamela Garretson Eric & Kathy Reinstein Daniel & Joanne Goldberg with Michael & Wendy Sachs Leonard & Rita Goldschmidt Lewis & Phyllis Sank Edward & Debbie Goodman David & Lois Schilling David & Glori Graziano Sharey Nancy Schwartz & Sean Bailey Jason & Lorie Grebin Tom Singer & Lisa Chenofsky Mark & Deborah Hager Beth Sklar-Baker James Hamant & Barbara Rosen Tefilo Stuart & Hannah Slavin Peter & Kelly Heinze David & Robin Siavit Syma & Sumner Herzog Israel Mario & Wily Solodkin Steven & Janet Hess David & Joanne Strauss Philip & Sue Hoch Richard & Wendy Straussman Jonathan & Jamie James and each William & Jenifer Strugger Jeff & -Ellen Kagan Terrence Sullivan & Miranda Aaron Michael & Gail Kanef Stephen & Susan Thomas Michael & Barbara Kanefsky other? Matthew & Stacy White Adam & Kacey Karp David & Jill Williams Dean & Elisabeth Kravitz John & Karen Williams William Kritzberg & Ruth Landa T Karl & Roberta Wolfe David & Mara Lateiner urn th e page Judith Wolochow-Kisch Richard & Claudia Lechtman Philippe & Adrienne Zimmerman to find out! Page 2 Temple Sharey Tefilo-Israel Bulletin Schedule of Services Friday, November 5 Friday, November 19 Clergy Rabbi Daniel M. -

KHM Academic Jewish Studies

Volume III, Issue 3 December 11, 2009/24 Kislev 5770 KOL HAMEVASER The Jewish Thought Magazine of the Yeshiva University Student Body Academic Interviews with, and Jewish Studies Articles by: Dr. David Berger, R. Dr. Richard Hidary, R. Dr. Joshua Berman, and Dr. Shawn-Zelig Aster p. 6, 8, 9, and 13 Jewish Responses to Wellhausen’s Docu- mentary Hypothesis AJ Berkovitz, p. 14 Tsiluta ke-Yoma de-Is- tana: Creating Clarity in the Beit Midrash Ilana Gadish, p. 18 Bible Study: Interpre- tation and Experience Ori Kanefsky, p. 19 Religious Authenticity and Historical Con- sciousness Eli Putterman on p. 20 Kol Hamevaser Contents Kol Hamevaser Volume III, Issue 3 The Student Thought Magazine of the Yeshiva December 11, 2009 24 Kislev 5770 University Student body Editorial Shlomo Zuckier 3 Academic Jewish Studies: Benefits and Staff Dangers Editors-in-Chief Letter-to-the-Editor Sarit Bendavid Shaul Seidler-Feller Mordechai Shichtman 5 Letter-to-the-Editors Associate Editor Academic Jewish Studies Shlomo Zuckier Staff 6 An Interview with Dr. David Berger Layout Editor Rabbi Dr. Richard Hidary 8 Traditional versus Academic Talmud Menachem Spira Study: “Hilkhakh Nimrinhu le-Tarvaihu” Editor Emeritus Shlomo Zuckier 9 An Interview with Rabbi Dr. Joshua Alex Ozar Berman Staff Writers Staff 13 An Interview with Dr. Shawn-Zelig Aster Yoni Brander Jake Friedman Abraham Jacob Berkovitz 14 Jewish Responses to Wellhausen’s Doc- Ilana Gadish umentary Hypothesis Nicole Grubner Nate Jaret Ilana Gadish 18 Tsiluta ke-Yoma de-Istana: Creating Clar- Ori Kanefsky ity in the Beit Midrash Alex Luxenberg Emmanuel Sanders Ori Kanefsky 19 Bible Study: Interpretation and Experi- Yossi Steinberger ence Jonathan Ziring Eli Putterman 20 Religious Authenticity and Historical Copy Editor Consciousness Benjamin Abramowitz Dovid Halpern 23 Not by Day and Not by Night: Jewish Webmaster Philosophy’s Place Reexamined Ben Kandel General Jewish Thought Cover Design Yehezkel Carl Nathaniel Jaret 24 Reality Check?: A Response to Mr. -

Study Guide REFUGE

A Guide for Educators to the Film REFUGE: Stories of the Selfhelp Home Prepared by Dr. Elliot Lefkovitz This publication was generously funded by the Selfhelp Foundation. © 2013 Bensinger Global Media. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements p. i Introduction to the study guide pp. ii-v Horst Abraham’s story Introduction-Kristallnacht pp. 1-8 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 8-9 Learning Activities pp. 9-10 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Kristallnacht pp. 11-18 Enrichment Activities Focusing on the Response of the Outside World pp. 18-24 and the Shanghai Ghetto Horst Abraham’s Timeline pp. 24-32 Maps-German and Austrian Refugees in Shanghai p. 32 Marietta Ryba’s Story Introduction-The Kindertransport pp. 33-39 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 39 Learning Activities pp. 39-40 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Sir Nicholas Winton, Other Holocaust pp. 41-46 Rescuers and Rescue Efforts During the Holocaust Marietta Ryba’s Timeline pp. 46-49 Maps-Kindertransport travel routes p. 49 2 Hannah Messinger’s Story Introduction-Theresienstadt pp. 50-58 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 58-59 Learning Activities pp. 59-62 Enrichment Activities Focusing on The Holocaust in Czechoslovakia pp. 62-64 Hannah Messinger’s Timeline pp. 65-68 Maps-The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia p. 68 Edith Stern’s Story Introduction-Auschwitz pp. 69-77 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 77 Learning Activities pp. 78-80 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Theresienstadt pp. 80-83 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Auschwitz pp. 83-86 Edith Stern’s Timeline pp.