Ebook As Diasporas Dos Judeus E Cristaos.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cihannüma TARİH VE COĞRAFYA ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL of HISTORY and GEOGRAPHY STUDIES

Cihannüma TARİH VE COĞRAFYA ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL OF HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY STUDIES CİLT / VOLUME II SAYI / ISSUE 2 Aralık / December 2016 İZMİR KÂTİP ÇELEBİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL VE BEŞERİ BİLİMLER FAKÜLTESİ Cihannüma TARİH VE COĞRAFYA ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL OF HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY STUDIES Sahibi/Owner İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi Sosyal ve Beşeri Bilimler Fakültesi adına Prof. Dr. Turan GÖKÇE Editörler / Editors Doç. Dr. Cahit TELCİ Yrd. Doç. Dr. Beycan HOCAOĞLU Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü / Responsible Editor Yrd. Doç. Dr. Beycan HOCAOĞLU Yayın Kurulu / Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Turan GÖKÇE Prof. Dr. Levent KAYAPINAR Prof. Dr. Çiğdem ÜNAL Prof. Dr. Ayşe KAYAPINAR Prof. Dr. Yusuf AYÖNÜ Doç. Dr. Özer KÜPELİ Yrd. Doç. Dr. İrfan KOKDAŞ Yrd. Doç. Dr. Nilgün Nurhan KARA Yrd. Doç. Dr. Beycan HOCAOĞLU Yrd. Doç. Dr. Haydar YALÇIN Yayın Türü / Publication Type Hakemli Süreli yayın / Peer-reviewed Periodicals Yazışma Adresi / CorrespondingAddress İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi Sosyal ve Beşeri Bilimler Fakültesi, Balatçık-Çiğli/İzmir Tel: +90(232) 329 35 35-8508 Faks: +90(232) 329 35 19 Basımevi / Publishing House Meta Basım Matbaacılık Hizmetleri 87 sk. No:4/A Bornova/İzmir ISSN 2149-0678 Basım Tarihi / Publication Date Aralık / December 2016 Yılda iki sayı yayımlanan hakemli bir dergidir / Peer-reviewed journal published twice a year Yazıların yayın hakkı İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi’nindir / Copyright © by Izmir Katip Celebi University Cihannüma TARİH VE COĞRAFYA ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ JOURNAL OF HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY STUDIES Danışma – Hakem Kurulu / Advisory – Referee Board Prof. Dr. Kezban ACAR Manisa Celal Bayar Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Muhsin AKBAŞ İzmir Kâtip Çelebi Üniversitesi Prof. Dr. Kemal BEYDİLLİ 29 Mayıs Üniversitesi Prof. -

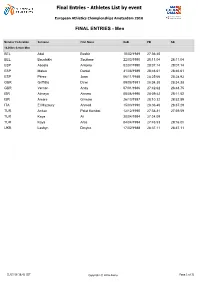

Final Entries - Athletes List by Event

Final Entries - Athletes List by event European Athletics Championships Amsterdam 2016 FINAL ENTRIES - Men Member Federation Surname First Name DoB PB SB 10,000m Senior Men BEL Abdi Bashir 10/02/1989 27:36.40 BEL Bouchikhi Soufiane 22/03/1990 28:11.04 28:11.04 ESP Abadía Antonio 02/07/1990 28:07.14 28:07.14 ESP Mateo Daniel 31/08/1989 28:46.61 28:46.61 ESP Pérez Juan 06/11/1988 28:25.66 28:28.93 GBR Griffiths Dewi 09/08/1991 28:34.38 28:34.38 GBR Vernon Andy 07/01/1986 27:42.62 28:48.75 ISR Almeya Aimeru 08/06/1990 28:09.42 28:11.52 ISR Amare Girmaw 26/10/1987 28:10.32 28:52.89 ITA El Mazoury Ahmed 15/03/1990 28:36.40 28:37.29 TUR $UÕNDQ Polat Kemboi 12/12/1990 27:38.81 27:59.59 TUR Kaya Ali 20/04/1994 27:24.09 TUR Kaya Aras 04/04/1994 27:48.53 29:16.0h UKR Lashyn Dmytro 17/02/1988 28:37.11 28:37.11 01/07/16 16:42 CET Copyright © 2016 Arena Page 1 of 32 Final Entries - Athletes List by event European Athletics Championships Amsterdam 2016 FINAL ENTRIES - Men Member Federation Surname First Name DoB PB SB 100m Senior Men AUT Fuchs Markus 14/11/1995 10.36 10.36 BUL Dimitrov Denis 10/02/1994 10.16 10.18 CZE Veleba Jan 06/12/1986 10.23 10.28 ESP Hortelano Bruno 18/09/1991 10.06 10.06 ESP Rodríguez Ángel David 25/04/1980 10.14 10.24 EST Niit Marek 09/08/1987 10.19 10.30 FRA Dutamby Stuart 24/04/1994 10.12 10.12 FRA Lemaitre Christophe 11/06/1990 9.92 10.09 FRA Vicaut Jimmy 27/02/1992 9.86 9.86 FRA Zeze Mickael-Meba 19/05/1994 10.21 10.21 GBR Edoburun Ojie 02/06/1996 10.16 10.19 GBR Ellington James 06/09/1985 10.11 10.11 GBR Gemili Adam 06/10/1993 -

The Portuguese Inquisition, a Inquisição Portuguesa, The

THE PORTUGUESE INQUISITION, The Portuguese Inquisition remains THE PORTUGUESE INQUISITION The case of Maria Lopes, burned at the stake in 1576 largely obscure. This book provides A INQUISIÇÃO PORTUGUESA, context and presents the tragic case of O caso de Maria Lopes, queimada na fogueira em 1576 !"#$"%&'()*+%,-)%.#*,%/'0"1%2#'0% the Azores burned at the stake. Ladinabooks NONFICTION Cover image by Kriszta Hernadi Porto, Portugal ISBN 978-0-9919946-0-1 Ladinabooks 90000 > Porto, Portugal www.ladinabooks.com www.ladinabooks.blogspot.ca [email protected] 9 780991 994601 Manuel Azevedo Fernanda Guimarães IV THE PORTUGUESE INQUISITION A INQUISIÇÃO PORTUGUESA Ladinabooks I 3$#*,%(456$*-)7%$1%89:;+%.#*,%(#$1,$1< =66%#$<-,*%#)*)#>)7%)?@)(,%2'#%,-)%A4',",$'1%'2%*-'#,%("**"<)*%2'#%,-)% (4#('*)*%'2%*,47B+%@#$,$@$*0%'#%#)>$)/C D'(B#$<-,%E%89:;%!"14)6%=F)>)7'%"17%3)#1"17"%G4$0"#H)* Ladinabooks I'#,'+%I'#,4<"6 ///C6"7$1"5''J*C@'0%% ///C6"7$1"5''J*C56'<*(',C@" 6"7$1"5''J*K<0"$6C@'0 3#'1,%@'>)#%"#,$*,L%M#$*F,"%N)#1"7$ D'>)#%7)*$<1%"17%,)?,%6"B'4,L%O"1B"%P"1,-'4#1'4, O#"1*6",'#*L%!"14)6%=F)>)7'+%=7)6$1"%I)#)$#"+%Q'H'%R)6<"7' I'#,4<4)*)%,#"1*@#$5)#L%3)#1"17"%G4$0"#H)* S7$,'#L%!"14)6%=F)>)7' Printed and bound in Canada ISBN 9780991994601 (pbk) 9780991994618 (ebook) 3'#,-@'0$1<%2#'0%&"7$1"5''J*L% The Portuguese Inquisition, the case of 12 yearold Violante Francesa, 1606. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Three Ways to Be Alien: Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World

three ways to be alien Travails & Encounters in the Early Modern World Sanjay Subrahmanyam Subrahmanyam_coverfront7.indd 1 2/9/11 9:28:33 AM Three Ways to Be Alien • The Menahem Stern Jerusalem Lectures Sponsored by the Historical Society of Israel and published for Brandeis University Press by University Press of New England Editorial Board: Prof. Yosef Kaplan, Senior Editor, Department of the History of the Jewish People, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, former Chairman of the Historical Society of Israel Prof. Michael Heyd, Department of History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, former Chairman of the Historical Society of Israel Prof. Shulamit Shahar, professor emeritus, Department of History, Tel-Aviv University, member of the Board of Directors of the Historical Society of Israel For a complete list of books in this series, please visit www.upne.com Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Three Ways to Be Alien: Travails and Encounters in the Early Modern World Jürgen Kocka, Civil Society and Dictatorship in Modern German History Heinz Schilling, Early Modern European Civilization and Its Political and Cultural Dynamism Brian Stock, Ethics through Literature: Ascetic and Aesthetic Reading in Western Culture Fergus Millar, The Roman Republic in Political Thought Peter Brown, Poverty and Leadership in the Later Roman Empire Anthony D. Smith, The Nation in History: Historiographical Debates about Ethnicity and Nationalism Carlo Ginzburg, History Rhetoric, and Proof Three Ways to Be Alien Travails & Encounters • in the Early Modern World Sanjay Subrahmanyam Brandeis The University Menahem Press Stern Jerusalem Lectures Historical Society of Israel Brandeis University Press Waltham, Massachusetts For Ashok Yeshwant Kotwal Brandeis University Press / Historical Society of Israel An imprint of University Press of New England www.upne.com © 2011 Historical Society of Israel All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Designed and typeset in Arno Pro by Michelle Grald University Press of New England is a member of the Green Press Initiative. -

Annual Report 1938

THE LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (FOUNDED IN 1760) GENERALLY KNOWN AS THE BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 1938 3 e o . -?-z & WOBURN HOUSE UPPER WOBURN PLACE LONDON, W.C.I 1939 3* 0. V2. £ FORM OF BEQUEST I bequeath to the LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF THE BRITISH JEWS (generally known as the Board of Deputies of British Jews) the sum of £ free of duty, to be applied to the general purposes of the said Board and the receipt of the Treasurer for the time being of the said Board shall be a sufficient discharge for the same. • * CONTENTS PAGE List of Officers of the Board 4 List of former Presidents ... ... ... ... 5 Alphabetical List of Deputies ... ... ... ... & List of Congregations and Institutions represented on the Board 18 Committees ... ... ... ... ... ... ••• 25 Annual Report—Introduction ... ... ... ... 29 Law, Parliamentary and General Purposes Committee 34 Aliens Committee ... ... ... ... 44 Education Committee ... ... ... ... ... 46 Finance Committee ... ... ... ... ... 47 Foreign Appeals Committee ... ... ... 48 Palestine Committee ... ... ... ... ... 49 Shechita Committee ... ... ... ... ... 52 ־... ... ... Jewish Defence Committee -!53 Joint Foreign Committee ••• ••• 56 Accounts ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 73 Secretaries for Marriages ... ... ... ... 79 «MRY 10 1939 AMERICAN. COMJMttl _ LIBRARY Officers of ffje President: NEVILLE J. LASKI, K.C. Vice-Presidents : SIR ROBERT WALEY COHEN, K.B.E. Br. ISRAEL FELDMAN. Treasurer : M. GORDON LIVERMAN, J.P. Hon. Auditors : M. CASH. JOSEPH MELLER, O.B.E. Solicitor : CHARLES H. L. EMANUEL, M.A. Auditors : Messrs. JEFFREYS, HENRY, MARKS & DIAMOND Secretary : A. G. BROTMAN, B.Sc. All Communications should be addressed to THE SECRETARY at :— Woburn House, Upper Woburn Place, London, W.C.I. -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

Museums, Monuments and Sites

Accommodation Alentejo Castro Verde Hotel A Esteva Hotel accommodation / Hotel / *** Address: Rua das Orquídeas,17780-000 Castro Verde Telephone: +351 286320110/8 Fax: +351 286320119 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.aesteva.pt Estremoz Pousada Rainha Santa Isabel Hotel accommodation / Pousada Address: Largo D. Dinis - Apartado 88 7100-509 Estremoz Telephone: +351 268 332 075 Fax: +351 268 332 079 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.pousadas.pt Évora Casa de SãoTiago Vitória Stone Hotel Tourism in a Manor House Hotel accommodation / Hotel / *** Address: Largo Alexandre Herculano, 2 - 7000 - 501 Address: Rua Diana de Liz, 5 7005-413 Évora ÉVORA Telephone: +351 266 707 174 Fax: +351 266 700 974 Telephone: 266702686 Fax: 226000357 E-mail: lui.cabeç[email protected] Website: http://www.albergariavitoria.com Golegã Casa do Adro da Golegã Tourism in the Country / Country Houses Address: Largo da Imaculada Conceição, 582150-125 Golegã Telephone: +351 96 679 83 32 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.casadoadrodagolega.pt 2013 Turismo de Portugal. All rights reserved. 1/232 [email protected] Grândola Santa Barbara dos Mineiros Hotel Rural Tourism in the Country / Rural Hotels Address: Aldeia Mineira do Lousal - Av. Frédéric Vélge 7570-006 Lousal Telephone: +351 269 508 630 Fax: +351 269 508 638 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.hotelruralsantabarbara.com Portalegre Rossio Hotel Hotel accommodation / Hotel / **** Address: Rua 31 de Janeiro nº 6 7300-211 Portalegre -

The Afro-Portuguese Maritime World and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations THE AFRO-PORTUGUESE MARITIME WORLD AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF SPANISH CARIBBEAN SOCIETY, 1570-1640 By David Wheat Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2009 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Jane G. Landers Marshall C. Eakin Daniel H. Usner, Jr. David J. Wasserstein William R. Fowler Copyright © 2009 by John David Wheat All Rights Reserved For Sheila iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been completed without support from a variety of institutions over the past eight years. As a graduate student assistant for the preservation project “Ecclesiastical Sources for Slave Societies,” I traveled to Cuba twice, in Summer 2004 and in Spring 2005. In addition to digitizing late-sixteenth-century sacramental records housed in the Cathedral of Havana during these trips, I was fortunate to visit the Archivo Nacional de Cuba. The bulk of my dissertation research was conducted in Seville, Spain, primarily in the Archivo General de Indias, over a period of twenty months in 2005 and 2006. This extended research stay was made possible by three generous sources of funding: a Summer Research Award from Vanderbilt’s College of Arts and Sciences in 2005, a Fulbright-IIE fellowship for the academic year 2005-2006, and the Conference on Latin American History’s Lydia Cabrera Award for Cuban Historical Studies in Fall 2006. Vanderbilt’s Department of History contributed to my research in Seville by allowing me one semester of service-free funding. -

Compras Fado Tours

Leisure | Ocio | Lazer | Loisir WINERIES | BODEGAS| PRODUTORES DE VINHO |CHAIS 10% RENT A BIKE VIEGUINI BIKES & SCOOTERS RENTAL 20% TOMAZ DO DOURO Pç. Ribeira, 5 T. +351 222 081 935 2G P 10% MARINHO’S R. Alegria, 695 4H CHOCOLATES | CHOCOLATS R. Nova da Alfandega, T. +351 914 306 838 2G 20% 2G P 10% 3G 40% Nov-Mar; 10% Apr-Oct | Abr-Out | Avr-Oct QUINTA DO SEIXO Tabuaço, TURISDOURO R. Canastreiros, 40-42 T. +351 222 006 418 O CAÇULA Praça Carlos Alberto, 473 10% CHOCOLATARIA EQUADOR R. Sá Bandeira, 637 3H | R. Flores 298 2G 10% RENT A SCOOTER VIEGUINI BIKES & SCOOTERS RENTAL 10% 3G MUSEUMS AND MONUMENTS | MUSEOS Y MONUMENTOS | Valença do Douro Reservar visita | book visit | reserver visite - [email protected] O CÃO QUE FUMA R. Almada, 405 5% Bonbons / Sweets, sugar almonds | bombones, almendras de azúcar | bombons, R. Nova da Alfandega,7 T. +351 914 306 838 2G CRUISE | CRUCERO | CRUZEIRO | CROISIÈRE - DOURO MUSEUS E MONUMENTOS | MUSÉES ET MONUMENTS T. +351 254 732 800 Visita à adega | Visita a la bodega | Visit to the winery | Visite au chai 10% O ESCONDIDINHO R. Passos Manuel, 152 3H amêndoas | bombons, amandes couvertes de sucre CONFEITARIA ARCÁDIA 10% THE GETAWAY VAN Lowcost Motorhome rental, includes airport transfer | Alquiler de 20% ROTA DO DOURO Av. Diogo Leite, 438 | V.N. Gaia T. +351 223 759 042 D 1 FREE Gratis | Grátis | Gratuit ARQUEOSSÍTIO R. D. Hugo, 5 2G 10% QUINTA DE SANTA CRISTINA R. Santa Cristina, 80 Veade, Celorico de Basto 10% Cash | dinero | dinheiro | espèces 5% Card | tarjeta | cartão | carte R. -

A NSF Physics Frontier Center Annual Report 2005-2006

A NSF Physics Frontier Center Annual Report 2005-2006 June 29, 2006 i Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Research Accomplishments and Plans 4 2.a Major Research Accomplishments . 4 2.a.1 Research Highlights . 4 2.a.2 Detailed Research Activities: MRC I- Theory . 5 2.a.3 Detailed Research Activities: MRC II- Structures in the Uni- verse ..................................... 20 2.a.4 Detailed Research Activities: MRC III - Cosmic Radiation Backgrounds ................................ 24 2.a.5 Detailed Research Activities: MRC IV - Particles from Space . 28 2.a.6 References . 32 2.b Research Organizational Details . 33 2.c Plans for the Coming Year . 33 3 Publications, Awards and Technology Transfers 40 3.a List of Publications in Peer Reviewed Journals . 40 3.b List of Publications in Peer Reviewed Conference Proceedings . 48 3.c Invited Talks by Institute Members . 52 3.d Honors and Awards . 56 3.e Technology Transfer . 57 4 Education and Human Resources 58 4.a Graduate and Postdoctoral Training . 58 4.a.1 Research Training . 58 4.a.2 Curriculum Development: . 62 4.b Undergraduate Education . 63 4.b.1 Undergraduate Research Experiences: . 63 4.b.2 Undergraduate Curriculum Development: . 64 4.c Educational Outreach . 65 4.c.1 K-12 Programs: Space Explorers . 66 4.c.2 Web-Based Educational Activities: . 69 4.c.3 Other: . 69 4.d Enhancing Diversity . 72 5 Community Outreach and Knowledge Transfer 74 5.a Visitor Participation in Center . 74 5.a.1 Long term visitors . 74 5.a.2 Short term and seminar visitors . 75 5.b Workshops and Symposia . -

Adopting HIV/AIDS Policy in Russia and South Africa, 1999-2008

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Political Science - Dissertations Affairs 2011 Treatment as a Common Good: Adopting HIV/AIDS Policy in Russia and South Africa, 1999-2008 Vladislav Kravtsov Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/psc_etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Kravtsov, Vladislav, "Treatment as a Common Good: Adopting HIV/AIDS Policy in Russia and South Africa, 1999-2008" (2011). Political Science - Dissertations. 97. https://surface.syr.edu/psc_etd/97 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT The goal of this dissertation is to increase our understanding of domestic policy responses to initiatives and expertise as provided by international health organizations. Although following international recommendations often improves domestic public health, in certain circumstances resistance to adopting them persists. My core theoretical argument suggests that a strong societal agreement about what constitutes the ―common good‖ served by state (e.g., ―social purpose‖) informs how domestic policy-makers evaluate the benefits of adopting international recommendations. This agreement also affects how governments frame the provision of treatment, decide which subpopulations should benefit from the consumption of public good, and choose their partners in policy implementation. To demonstrate the impact of social purpose I examine how, why and with what consequences Russia and South Africa adopted the external best case practices, guidelines, and recommendations in regard to the HIV/AIDS treatment.