International Conference Education and Language Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coordination and Ellipsis

Comprehensive Grammar Comprehensive Grammar Resources Resources Henk van Riemsdijk & István Kenesei, series editors Syntax of Dutch Syntax of DutchCoordination and Ellipsis Broekhuis Corver Hans Broekhuis Norbert Corver Syntax of Dutch Coordination and Ellipsis Comprehensive Grammar Resources Editors: Henk van Riemsdijk István Kenesei Hans Broekhuis Syntax of Dutch Coordination and Ellipsis Hans Broekhuis Norbert Corver With the cooperation of: Hans Bennis Frits Beukema Crit Cremers Henk van Riemsdijk Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants and financial support from: Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) Center for Language Studies University of Tilburg Truus und Gerrit van Riemsdijk-Stiftung Meertens Institute (KNAW) Utrecht University This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org). OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Cover design: Studio Jan de Boer, Amsterdam Layout: Hans Broekhuis ISBN 978 94 6372 050 2 e-ISBN 978 90 4854 289 5 DOI 10.5117/9789463720502 NUR 624 Creative Commons License CC BY NC (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) Hans Broekhuis & Norbert Corver/Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

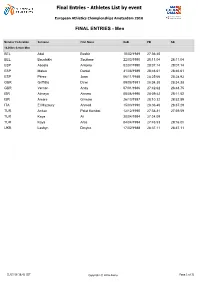

Final Entries - Athletes List by Event

Final Entries - Athletes List by event European Athletics Championships Amsterdam 2016 FINAL ENTRIES - Men Member Federation Surname First Name DoB PB SB 10,000m Senior Men BEL Abdi Bashir 10/02/1989 27:36.40 BEL Bouchikhi Soufiane 22/03/1990 28:11.04 28:11.04 ESP Abadía Antonio 02/07/1990 28:07.14 28:07.14 ESP Mateo Daniel 31/08/1989 28:46.61 28:46.61 ESP Pérez Juan 06/11/1988 28:25.66 28:28.93 GBR Griffiths Dewi 09/08/1991 28:34.38 28:34.38 GBR Vernon Andy 07/01/1986 27:42.62 28:48.75 ISR Almeya Aimeru 08/06/1990 28:09.42 28:11.52 ISR Amare Girmaw 26/10/1987 28:10.32 28:52.89 ITA El Mazoury Ahmed 15/03/1990 28:36.40 28:37.29 TUR $UÕNDQ Polat Kemboi 12/12/1990 27:38.81 27:59.59 TUR Kaya Ali 20/04/1994 27:24.09 TUR Kaya Aras 04/04/1994 27:48.53 29:16.0h UKR Lashyn Dmytro 17/02/1988 28:37.11 28:37.11 01/07/16 16:42 CET Copyright © 2016 Arena Page 1 of 32 Final Entries - Athletes List by event European Athletics Championships Amsterdam 2016 FINAL ENTRIES - Men Member Federation Surname First Name DoB PB SB 100m Senior Men AUT Fuchs Markus 14/11/1995 10.36 10.36 BUL Dimitrov Denis 10/02/1994 10.16 10.18 CZE Veleba Jan 06/12/1986 10.23 10.28 ESP Hortelano Bruno 18/09/1991 10.06 10.06 ESP Rodríguez Ángel David 25/04/1980 10.14 10.24 EST Niit Marek 09/08/1987 10.19 10.30 FRA Dutamby Stuart 24/04/1994 10.12 10.12 FRA Lemaitre Christophe 11/06/1990 9.92 10.09 FRA Vicaut Jimmy 27/02/1992 9.86 9.86 FRA Zeze Mickael-Meba 19/05/1994 10.21 10.21 GBR Edoburun Ojie 02/06/1996 10.16 10.19 GBR Ellington James 06/09/1985 10.11 10.11 GBR Gemili Adam 06/10/1993 -

Ebook As Diasporas Dos Judeus E Cristaos.Pdf

As Diásporas dos Judeus e Cristãos- -Novos de Origem Ibérica entre o Mar Mediterrâneo e o Oceano Atlântico. Estudos ORGANIZAÇÃO : José Alberto R. Silva Tavim Hugo Martins Ana Pereira Ferreira Ângela Sofia Benoliel Coutinho Miguel Andrade Lisboa Centro de História da Universidade de Lisboa 2020 Título As Diásporas dos Judeus e Cristãos-Novos de Origem Ibérica entre o Mar Mediterrâneo e o Oceano Atlântico. Estudos Organização José Alberto R. Silva Tavim, Hugo Martins, Ana Pereira Ferreira, Ângela Sofia Benoliel Coutinho e Miguel Andrade Revisão André Morgado Comissão científica Ana Isabel Lopez-Salazar Codes (U. Complutense de Madrid), Anat Falbel (U. Federal do Rio de Janeiro), Ângela Domingues (U. Lisboa), Beatriz Kushnir (Directora, Arq. Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro), Blanca de Lima (U. Francisco de Miranda, Coro; Acad. Nac. de la Historia-Capítulo Falcón, Venezuela), Claude B. Stuczynski (Bar-Ilan U.), Cynthia Michelle Seton-Rogers (U. of Texas-Dallas), Daniel Strum (U. São Paulo), Daniela Levy (U. São Paulo), Edite Alberto (Dep. Património Cultural/C. M. Lisboa; CHAM, FCSH-UNL), Elvira Azevedo Mea (U. Porto), Eugénia Rodrigues (U. Lisboa), Hernán Matzkevich (U. Purdue), Joelle Rachel Rouchou (Fund. Casa de Rui Barbosa, Rio de Janeiro), Jorun Poettering (Harvard U.), Maria Augusta Lima Cruz (ICS-U. do Minho; CHAM, FCSH, UNL), Maria Manuel Torrão (U. Lisboa), Moisés Orfali (Bar-Ilan U.), Nancy Rozenchan (U. de São Paulo), Palmira Fontes da Costa (U. Nova de Lisboa), Timothy D. Walker (U. Massachusetts Dartmouth) e Zelinda Cohen (Inst. do Património Cultural, Cabo Verde) Capa Belmonte, com Sinagoga Bet Eliahu. Fotografia de José Alberto R. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Brigid Guides Our Way Through the Light and Darkness of Our Time

y ISSUE 27 VOLUME 2 Proudly Serving Celts in North America Since 1991 FEBRUARY 2018 Brigid Guides our Way Through the Light and Darkness of our Time By CYNTHIA WALLENTINE HETHER we are ready or not, no season W arrives without AS BREXIT ‘cliff-edge’ fears grow, a forecast prepared for the change of some kind. The British Government and leaked by news website BuzzFeed re- portedly says the economy will be worse off after the country real question is whether leaves the European Union, regardless of what trade deal is the change is welcomed as struck with the bloc. It is scheduled to depart at 11 PM UK time growth or blunt require- on Friday, March, 29, 2019. [Read more inside on page 8] ment. With the passage of the Festi- val of Imbolg in early Febru- ary, we are now in the season of light, the territory of the great Celtic goddess Brigid. With a legacy that stretches from the prehistoric tribes of Europe to refined Christian cathedrals cen- turies later, the goddess withstands time. In his work, The Festival of Brigit, Irish author Seamus O’ Cathain writes “that Brigit, whose very name embod- ies the concept of growth, should have remained such a constant icon of ven- IMAGE: Brigid by tattereddreams on DeviantArt. eration for heathen and Christian Celt March 1 is St. David’s Day, the national day of Wales, and alike.” way, others turn to the vague leanings new energy. Whether your tool is a pen, celebrated by Welsh around the world. [Read more page 6] At Imbolg, the load of winter lightens. -

Notes on Proto-Mansi Word-Final Vocalism

Juho Pystynen Helsinki Notes on Proto-Mansi word-final vocalism 1. Introduction The history of the Mansi vocalism has been a subject of research already for more than a century. However, all three monographs published on the topic thus far (Hazay 1907, Kannisto 1919, Steinitz 1955) only treat first-syllable vocalism. Slightly more detail is found in Honti (1982 = GOV), who presents full Proto-Mansi (PMs) reconstructions in his comparative Ob-Ugric lexicon, but he still gives no overview of either the PMs second-syllable vocalism, its development from Proto-Ob-Ugric, or its development into the attested Mansi varieties. In this paper I attempt to take a first step towards this goal, focusing on word-final vowels in nominal stems. As research material, the 724 Proto-Mansi reconstructions and 105 additional etymological cognate sets presented in GOV would seem to cover the bulk of the old inherited vocabulary of Mansi, and they provide a relatively comprehensive basis for probing the historical development of the Mansi varieties. To this could be still added a number of words of old Uralic heritage not covered by Honti due to the absence of cognates in Khanty (e.g. the reflexes of Proto-Uralic kojwa* ‘birch’, *lämə ‘broth’, *wetə ‘water’). Such examples are however not numerous, and they do not seem to change the emerging big picture. Substantially more additional data can be found in the Mansi dialect dictionaries based on the collections of Munkácsi and Kannisto, but their analy- sis would first require further etymological work; they certainly contain much newer vocabulary from various other sources (e.g. -

Reference Grammar & Lexicon (Incomplete)

Bwangxùd Reference Grammar and Lexicon Andrew Ray Revised: July 6, 2018 Contents 1 Foreword ...................................................... 3 2 Overview ...................................................... 4 2.1 Dialects....................................................... 4 3 Phonology ...................................................... 5 3.1 Inventory...................................................... 5 3.2 Tones and sandhi ................................................. 5 3.3 Morphosyntax................................................... 6 3.4 Phonological processes.............................................. 6 3.5 Vowel allophony.................................................. 7 3.6 Consonant allophony............................................... 7 3.7 Dialectal variations in phonology ........................................ 8 3.7.1 Western coastal dialect............................................. 8 3.7.2 Northern interior dialect............................................ 8 3.7.3 Southern coastal dialect............................................. 8 3.7.4 Southern interior dialect............................................ 8 4 Simple morphology and syntax ......................................... 9 4.1 Word classes.................................................... 9 4.2 Word order..................................................... 9 4.3 Deniteness and surprise............................................. 9 4.4 Noun roles..................................................... 10 4.5 Proximity..................................................... -

Winter in the Urals 7 Mountain Ski Resort “Stozhok” Mountain Ski Resort “Stozhok” Is a Quiet and Comfortable Place for Winter Holidays

WinterIN THE URALS The Government of Sverdlovsk Region mountain ski resorts The Ministry of Investment and Development of Sverdlovsk Region ecotourism “Tourism Development Centre of Sverdlovsk Region” 13, 8 Marta Str., entrance 3, 2nd fl oor Ekaterinburg, 620014 active tourism phone +7 (343) 350-05-25 leisure base wellness winter fi shing gotoural.соm ice rinks ski resort FREE TABLE OF CONTENTS MOUNTAIN SKI RESORTS 6-21 GORA BELAYA 6-7 STOZHOK 8 ISET 9 GORA VOLCHIHA 10-11 GORA PYLNAYA 12 GORA TYEPLAYA 13 GORA DOLGAYA 14-15 GORA LISTVENNAYA 16 SPORTCOMPLEX “UKTUS” 17 GORA YEZHOVAYA 18-19 GORA VORONINA 20 FLUS 21 ACTIVE TOURISM 22-23 ECOTOURISM 24-27 ACTIVE LEISURE 28-33 LEISURE BASE 34-35 WELLNESS 36-37 WINTER FISHING 38-39 NEW YEAR’S FESTIVITIES 40-41 ICE RINKS, SKI RESORT 42-43 WINTER EVENT CALENDAR 44-46 LEGEND address chair lift GPS coordinates surface lift website trail for mountain skis phone trail for running skis snowtubing MAP OF TOURIST SITES Losva 1 Severouralsk Khanty-Mansi Sosnovka Autonomous Okrug Krasnoturyinsk Karpinsk 18 Borovoy 31 Serov Kytlym Gari 2 Pavda Sosva Andryushino Tavda Novoselovo Verkhoturye Alexandrovskaya Raskat Kachkanar Tura Iksa 3 Verhnyaya Tura Tabory Perm Region Niznyaya Tura Kumaryinskoe Basyanovskiy Kushva Tagil Niznyaya Salda Turinsk 27 29 Verkhnyaya Salda Nitza 4 Nizhny Tagil 26 1 Niznyaya Sinyachikha Chernoistochinsk Visimo-Utkinsk Alapaevsk 7 Verkhnie Tavolgi Irbit Turinskaya Sloboda Ust-Utka Chusovaya Visim Aramashevo Artemovskiy Verkhniy Tagil Nevyansk Rezh 10 25 Chusovoe 2 Shalya 23 Novouralsk -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Party Organisation and Party Adaptation: Western European Communist and Successor Parties Daniel James Keith UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, April, 2010 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature :……………………………………… iii Acknowledgements My colleagues at the Sussex European Institute (SEI) and the Department of Politics and Contemporary European Studies have contributed a wealth of ideas that contributed to this study of Communist parties in Western Europe. Their support, generosity, assistance and wealth of knowledge about political parties made the SEI a fantastic place to conduct my doctoral research. I would like to thank all those at SEI who have given me so many opportunities and who helped to make this research possible including: Paul Webb, Paul Taggart, Aleks Szczerbiak, Francis McGowan, James Hampshire, Lucia Quaglia, Pontus Odmalm and Sally Marthaler. -

Studies in Uralic Vocalism III*

Mikhail Zhivlov Russian State University for the Humanities; School for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, RANEPA (Moscow); [email protected] Studies in Uralic vocalism III* The paper discusses three issues in the history of Uralic vocalism: the change of Proto-Uralic vowel combination *ä-ä to Proto-Finnic *a-e, the fate of Proto-Uralic * before velar consonants in Finnic, Saami and Mordvin, and the possibility of reconstructing two distinct vowels in PU non-initial syllables instead of *a of the traditional reconstruction. It is argued that the development of Uralic vocalism must be described in terms of strict sound laws, and not of “sporadic developments”. Keywords: Uralic languages, Finno-Ugric languages, historical phonetics, proto-language re- construction, Proto-Uralic vocalism. “It was customary to vindicate this unpredictability of the PU reconstruction either by claiming that phonetic development is not governed by laws, but only follows certain trends of limited influence … , or by stating that law-abiding development is accompanied by numerous changes of a sporadic nature. Lately, however, in Uralic studies (as well as in other branches of linguistics) the ideas of classical comparative linguistics — among them the Neo-grammarian-type notion of strict phonetic laws — have gained momentum again. This at once creates a dilemma: to find the lacking laws — or to reconsider the reconstruction itself” [Helimski 1984: 242]. 0. Introduction The present article is based on the following assumption: the historical development of the Uralic languages follows the same principles as the historical development of any other lan- guage family in the world. Therefore, we must apply in Uralic studies the same Neo- grammarian methodology that was successfully applied in the study of other language fami- lies, notably Indo-European, but also Algonquian, Austronesian, Bantu and many others. -

Angol-Magyar Nyelvészeti Szakszótár

PORKOLÁB - FEKETE ANGOL- MAGYAR NYELVÉSZETI SZAKSZÓTÁR SZERZŐI KIADÁS, PÉCS 2021 Porkoláb Ádám - Fekete Tamás Angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótár Szerzői kiadás Pécs, 2021 Összeállították, szerkesztették és tördelték: Porkoláb Ádám Fekete Tamás Borítóterv: Porkoláb Ádám A tördelés LaTeX rendszer szerint, az Overleaf online tördelőrendszerével készült. A felhasznált sablon Vel ([email protected]) munkája. https://www.latextemplates.com/template/dictionary A szótárhoz nyújtott segítő szándékú megjegyzéseket, hibajelentéseket, javaslatokat, illetve felajánlásokat a szótár hagyományos, nyomdai úton történő előállítására vonatkozóan az [email protected] illetve a [email protected] e-mail címekre várjuk. Köszönjük szépen! 1. kiadás Szerzői, elektronikus kiadás ISBN 978-615-01-1075-2 El˝oszóaz els˝okiadáshoz Üdvözöljük az Olvasót! Magyar nyelven már az érdekl˝od˝oközönség hozzáférhet német–magyar, orosz–magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakhoz, ám a modern id˝ok tudományos világnyelvéhez, az angolhoz még nem készült nyelvészeti célú szak- szótár. Ennek a több évtizedes hiánynak a leküzdésére vállalkoztunk. A nyelvtudo- mány rohamos fejl˝odéseés differenciálódása tovább sürgette, hogy elkészítsük az els˝omagyar-angol és angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakat. Jelen kötetben a kétnyelv˝unyelvészeti szakszótárunk angol-magyar részét veheti kezébe az Olvasó. Tervünk azonban nem el˝odöknélküli vállalkozás: tudomásunk szerint két nyelvészeti csoport kísérelt meg a miénkhez hasonló angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárat létrehozni. Az els˝opróbálkozás