Hersh Gross and His Boiberiker Kapelye (1927-1932)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rokdim-Nirkoda” #99 Is Before You in the Customary Printed Format

Dear Readers, “Rokdim-Nirkoda” #99 is before you in the customary printed format. We are making great strides in our efforts to transition to digital media while simultaneously working to obtain the funding מגזין לריקודי עם ומחול .to continue publishing printed issues With all due respect to the internet age – there is still a cultural and historical value to publishing a printed edition and having the presence of a printed publication in libraries and on your shelves. עמותת ארגון המדריכים Yaron Meishar We are grateful to those individuals who have donated funds to enable והיוצרים לריקודי עם financial the encourage We editions. printed recent of publication the support of our readers to help ensure the printing of future issues. This summer there will be two major dance festivals taking place Magazine No. 99 | July 2018 | 30 NIS in Israel: the Karmiel Festival and the Ashdod Festival. For both, we wish and hope for their great success, cooperation and mutual YOAV ASHRIEL: Rebellious, Innovative, enrichment. Breaks New Ground Thank you Avi Levy and the Ashdod Festival for your cooperation 44 David Ben-Asher and your use of “Rokdim-Nirkoda” as a platform to reach you – the Translation: readers. Thank you very much! Ruth Schoenberg and Shani Karni Aduculesi Ruth Goodman Israeli folk dances are danced all over the world; it is important for us to know and read about what is happening in this field in every The Light Within DanCE place and country and we are inviting you, the readers and instructors, 39 The “Hora Or” Group to submit articles about the background, past and present, of Israeli folk Eti Arieli dance as it is reflected in the city and country in which you are active. -

Notes from New York: Names, Networks, and Connectors in Art History

ISSN: 2471-6839 Notes from New York: Names, Networks, and Connectors in Art History Susan Greenberg Fisher Chaim Gross Foundation The Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation, located in Greenwich Village, is the historic home and studio of American sculptor Chaim Gross (1904–1991) (fig. 1). The foundation is housed in a four story townhouse, with the artist's dramatic sculpture studio on the ground floor (fig. 2). Gross built the studio in 1963 when he purchased the building. It was his final workspace after a long history of studios he had in the Village beginning in the 1930s.1 He and his wife Renee rented the second floor, and in the third floor living space, Gross installed a portion of what had grown to Fig. 1. Home and studio of sculptor Chaim Gross at 526 LaGuardia Place, be an extensive art collection of over one thousand works by Greenwich Village, New York City, built circa 1830 and purchased by Gross 2 his American and European contemporaries (fig. 3). Gross and his wife Renee Gross in 1963. This photograph is circa 1970. The building admired artist house museums that he had seen during his is now The Renee & Chaim Gross Foundation. Archives, The Renee & travels in Europe after World War II, such as the Delacroix Chaim Gross Foundation, New York. museum in Paris, and it was his dream to have a house museum similar to the European models. He incorporated the foundation as a nonprofit organization in 1989, shortly before his death in 1991. Susan Greenberg Fisher. “Notes from New York: Names, Networks, and Connectors in Art History.” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 2 no. -

Contemporary Jewish Music and Culture Spring 2013 Judaic Studies Special Topics 563:225:01 Tuesday and Thursdays 6:10-7:30Pm Dr

Contemporary Jewish Music and Culture Spring 2013 Judaic Studies Special Topics 563:225:01 Tuesday and Thursdays 6:10-7:30pm Dr. Mark Kligman ([email protected]) Office Hours Tuesday 5:00-6:00, Room 203 12 College Ave, Rm 107 Course Description This course will look at Contemporary Jewish Music. “Contemporary” for this class is defined as music created from the 1950s to the present. The thrust of this investigation will be Jewish music in America and Israel since the 1970s. In order to contextualize Jewish music in America the music prior to this period, the music of Jews with roots in Europe, will begin our discussion. Issues such as Jewish identity, authenticity, religion and culture will be ongoing in our discussion. One overarching topic is the ongoing nature of tradition and innovation. An ethnographic approach will inform the issues to see your culture plays a role in shaping, informing and intrinsically a part of music in Jewish life. Contemporary music in Israel will also be examined and will highlight some similarities to music in America as well as illustrate key differences. The course will be divided into three almost equal sections: contemporary Jewish music in America in Religious contexts (Orthodox, Conservative and Reform); klezmer music; and, Israeli music. The readings assigned for each course will provide a good deal of historical and contextual information as related to musicians and musical genres. At each class sessionsmusical examples (both audio and video) will demonstrate key musical selections. Historical, informational and cultural background of Jewish life will be part of the readings for each session. -

Geshem’ by Cantor Moshe Haschel

The Outpouring for ‘Geshem’ by Cantor Moshe Haschel The Mishna (Rosh Hashanah, chapter 1 mishna 2) tells us that on Sukkot the world is judged for rain. The Talmud (Taanit 7a) says in the name of Rav Yosef that the world’s dependence on rain for its sustenance is so total that rainfall is compared to the revival of the dead. This is the reason says Rav Yosef, why the Rabbis put the phrase – ‘ Mashiv Haruach uMorid Hageshem’ – ‘He makes the wind to blow and the rain to fall’ in the second blessing of the Amida which speaks about Divine Might and concludes with ‘Blessed are You, Lord, who revives the dead’. The Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 16a) brings Rabbi Yehuda’s view that the world is judged on all aspects already on Rosh Hashanah but the final judgment is sealed for each feature only in its specific time; for grain on Pesach, for fruits of trees on Shavuot and for rain on Sukkot. Rabbi Yehoshua Ibn Shuaib (13th century Spain) in his work ‘Derashot al haTorah’ (derasha for Shemini Atzeret) explains this notion in connection with rain that the amount of rain that will fall during the coming year is in fact determined already on Rosh Hashanah. However, on Sukkot it is decided where i.e. on which parts of the world it would fall, and how i.e. whether it would be beneficial to the world or otherwise. This idea is reflected in the Liturgical poem ‘Af Beri’ by Rabbi Eleazar haKalir recited at the Shemini Atzeret Mussaf repetition. -

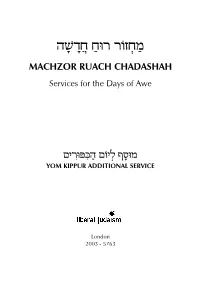

Yom Kippur Additional Service

v¨J¨s£j jUr© rIz§j©n MACHZOR RUACH CHADASHAH Services for the Days of Awe ohrUP¦ ¦ F©v oIh§k ;¨xUn YOM KIPPUR ADDITIONAL SERVICE London 2003 - 5763 /o¤f§C§r¦e§C i¥T¤t v¨J¨s£j jU© r§ «u Js¨ ¨j c¥k o¤f¨k h¦T©,¨b§u ‘I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you.’ (Ezekiel 36:26) This large print publication is extracted from Machzor Ruach Chadashah EDITORS Rabbi Dr Andrew Goldstein Rabbi Dr Charles H Middleburgh Editorial Consultants Professor Eric L Friedland Rabbi John Rayner Technical Editor Ann Kirk Origination Student Rabbi Paul Freedman assisted by Louise Freedman ©Union of Liberal & Progressive Synagogues, 2003 The Montagu Centre, 21 Maple Street, London W1T 4BE Printed by JJ Copyprint, London Yom Kippur Additional Service A REFLECTION BEFORE THE ADDITIONAL SERVICE Our ancestors acclaimed the God Whose handiwork they read In the mysterious heavens above, And in the varied scene of earth below, In the orderly march of days and nights, Of seasons and years, And in the chequered fate of humankind. Night reveals the limitless caverns of space, Hidden by the light of day, And unfolds horizonless vistas Far beyond imagination's ken. The mind is staggered, Yet soon regains its poise, And peering through the boundless dark, Orients itself anew by the light of distant suns Shrunk to glittering sparks. The soul is faint, yet soon revives, And learns to spell once more the name of God Across the newly-visioned firmament. Lift your eyes, look up; who made these stars? God is the oneness That spans the fathomless deeps of space And the measureless eons of time, Binding them together in deed, as we do in thought. -

Michael Tilson Thomas: the Maestro Inspired by Yiddishkeit the Acclaimed Conductor Reveals How the Adventure and Activism of Yiddish Theatre Influences His Work

Michael Tilson Thomas: The maestro inspired by Yiddishkeit The acclaimed conductor reveals how the adventure and activism of Yiddish theatre influences his work. By Jessica Duchen, January 19, 2012 If you ever imagined that the conductor Michael Tilson Thomas might be Welsh, think again. "Thomas" was originally "Thomashefsky": the name signals an extraordinary heritage that underpins this much-loved maestro's instinct for performance and showbusiness. He is currently in the UK to conduct the London Symphony Orchestra in a series of concerts focusing on the music of Claude Debussy, the 150th anniversary of whose birth falls this year. And though the Barbican concert hall may seem a long way from New York's Lower East Side and its Yiddish-speaking immigrants of the 1880s, perhaps Tilson Thomas brings something of their spirit with him. His grandparents, Bessie and Boris Thomashefsky, were prominent stars in the development of American Yiddish theatre in Manhattan. They went on to own theatres in the area, to publish a magazine, to encourage generations of young actors, to raise funds for many social causes and to be at the cutting edge of thespian life in general. After Boris died in 1939, it was reported that a crowd 30,000 strong lined the street on the day of his funeral. "When I was growing up I was surrounded by people who had a connection with the Yiddish theatre, which had an attitude of great adventure and of social activism," says Tilson Thomas, who is 67. "Much of its repertoire concerned issues of the time: women's rights, labour rights and concerns regarding assimilation, language and more. -

Ulrich Museum of Art

HLC Accreditation 2016-2017 Evidence Document Academic Affairs Ulrich Museum of Art Martin H. Bush Outdoor Sculpture Collection Additional information: See more information on the Ulrich Museum’s web pages: http://webs.wichita.edu/?u=ulrichmuseum&p=/art/outdoorsculpturecollection/ (Accessed May 3, 2016.) Ulrich Museum of Art - Wichita State University ABOUT US | ART | NEWS & EVENTS | VISIT | GET INVOLVED | CONTACT US MARTIN H. BUSH OUTDOOR SCULPTURE COLLECTION The Ulrich Museum of Art’s Martin H. Bush Outdoor Sculpture Collection boasts 76 works spread across the 330-acre Wichita State University campus. Public Art Review named this collection among the Top Ten campus sculpture collections in 2006. Take the online sculpture tour. Download a printable PDF map of the outdoor sculpture collection. Submit the Tour Request Form and schedule a free, guided tour of the outdoor sculpture collection for groups of 10 or more. http://webs.wichita.edu/?u=ulrichmuseum&p=/art/outdoorsculpturecollection/[2016-05-03 16:18:32] 51. Jo Davidson (American, 1883–1952) 66. Ernest Trova Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1947 (American, 1927–2009) Bronze, 20 x 20 x 10 1/2 in. Profile Canto L.L. #8, 1976 Museum Purchase with Student Government Stainless steel, 57 1/4 x 48 x 143 1/2 in. Association Funds and Gift of Pat Wallingford in Gift of Lanny Lamont in honor of Vicki Lamont memory of Sam Wallingford In Storage 67. Theodore Roszak (American, born Poland 1907–1981) 52. Aristide Maillol (French, 1861–1944) Skylark, 1950–51 Bust of Renoir, 1907 Bronze, 96 x 77 x 22 in. Bronze, 14 1/2 x 10 x 11 in. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

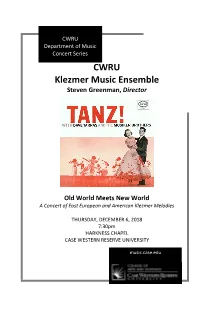

Klezmer Program 12.06.18

CWRU DepArtment oF MusIc Concert SerIes CWRU Klezmer Music Ensemble Steven Greenman, Director Old World Meets New World A Concert of East European and American Klezmer Melodies THURSDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2018 7:30pm HARKNESS CHAPEL CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY musIc.cAse.edu Welcome to Florence-Harkness Memorial Chapel RESTROOMS Women’s And men’s restrooms Are locAted on the mAIn level oF the buildIng. PAGERS, CELL PHONES, COMPUTERS, IPADS AND LISTENING DEVICES As A courtesy to the perFormers And AttendIng AudIence members, pleAse power oFF All electronic And mechanicAl devIces, Including pagers, cellulAr telephones, computers IPAds, wrIst wAtch AlArms, etc. prIor to the stArt oF the concert. PHOTOGRAPHY, VIDEO AND RECORDING DEVICES As A courtesy to the perFormers And AudIence members, photogrAphy And vIdeogrAphy Is strIctly prohibIted durIng the perFormAnce. FACILITY GUIDELINES In order to preserve the beAuty And cleAnlIness oF the hAll, no Food or beverAge, Including wAter, Is permItted. A DrInkIng FountAIn Is locAted neAr the restrooms beside the classroom. IN THE EVENT OF AN EMERGENCY ContAct An usher or A member oF the house stAFF IF you requIre medIcAl AssIstAnce. Emergency exIts Are cleArly marked throughout the buIldIng. Ushers And house staFF wIll provIde Instruction In the event oF An emergency. musIc.cAse.edu/FAcIlItIes/Florence-harkness-memorIAl-chApel/ Program “Rumania” Bulgar AlexAnder OlshAnetsky -from the recordIng Tanz! With Dave Tarras and the Musiker Brothers - 1955 Chused’l #10 from International HeBrew Wedding Music (“HAsIdIc DAnce #10) by W. KostAkowsky - 1916 Dem Trisker Rebn’s Khosid TrAdItIonAl/DAve TArrAs (“The TrIsker Rebbe’s DAnce”) Recorded - 1925 Yiddish Bulgar Max EpsteIn (“JewIsh BulgAr”) Recorded wIth the HymIe JAcobson OrchestrA - 1947 Romanian Fantasy Pt. -

American Folk Music and Folklore Recordings 1985: a Selected List

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 277 618 SO 017 762 TITLE American Folk Music and Folklore Recordings 1985: A Selected List. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. American Folklife Center. PUB DATE 86 NOTE 17p.; For the recordings lists for 1984 and 1983, see ED 271 353-354. Photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROM Selected List, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20540. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Black Culture; *Folk Culture; *Jazz; *Modernism; *Music; Popular Culture ABSTRACT Thirty outstanding records and tapes of traditional music and folklore which were released in 1985 are described in this illustrated booklet. All of these recordings are annotated with liner notes or accompanying booklets relating the recordings to the performers, their communities, genres, styles, or other pertinent information. The items are conveniently available in the United States and emphasize "root traditions" over popular adaptations of traditional materials. Also included is information about sources for folk records and tapes, publications which list and review traditional music recordings, and relevant Library of Congress Catalog card numbers. (BZ) U.111. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office or Educao onal Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) This document hes been reproduced u received from the person or o•panizahon originating it Minor changes nave been made to improve reproduction ought) Points of view or opinions stated in this docu mint do not necessarily represent Olhcrai OERI posrtio.r or policy AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC AND FOLKLORE RECORDINGS 1985 A SELECTED LIST Selection Panel Thomas A. Adler University of Kentucky; Record Review Editor, Western Folklore Ethel Raim Director, Ethnic Folk Arts Center Don L. -

Thropist, Art Festival

banker, developer ofmica, philanthropist, art Festival. • See: EJ; NAW:modern; DAB, 8; collector, NYC; fdr Jerome TaishoffFound; NYTimes, Aug 5 1966, 31:1. governor LI U; officer Air Force Historical Found.· See: NYTimes, Dec 211964, 29:1. Tamkin, Hayward; b. Koretz, Russia, Sep 121908. T Taishoff, SolJoseph; b. Minsk, Oct 81904; To Boston 1912. • BS, LLB Boston.U. • d. Aug 15 1982. Lawyer, Boston; dir Boston U Legal Aid To Washington DC 1906. • Newspaperman, Bureau; active Center for Adult Education, Tabachinsky, Benjamin; b. Bialystok, Mar Washington DC; co-fdr Broadcasting Magazine; Curry School ofExpression. • See: WWIAJ, 311895; d. Amityville, NY, Aug 6 1967. staff US Daily; bd WashingtonJournalism 1938. To US 1938/1939. • Communal exec; mem Center.· See: WWIAJ, 1938; WWWIA, 8. Bialystok Municipal Council; exec dirJewish Tananbaum, Alfred A; b. NYC, Mar 29 Labor Com; active cbmmunal education, Talalay,Joseph A; b. Russia, ca 1892; d. 1909; d.NYC, May 171971. Polish ORT,Jewish Socialist Bund;contribu New Haven, Oct 1961. Fordham Law. • Textile business exec; exec tor Yiddish press. • See:AJYB, 69:613;JTA To US 1940. • PhD U St Petersburg, Yonkers Raceway; a fdr Albert Einstein CoIl of DNB, Aug 8 1967; NYTimes, Aug 8 1967, 39:2. engineering degree Imperial Inst of Med, Heb Inst (White Plains), Garment Technology (Moscow). • Rubber technologist, Center Cong; ldr Fedn ofJewish Tabachnik, Abraham Ber (Avrohom); b. invented process to make latex foam; Philanthropies. • See:AJYB, 73:636; NYTimes, Nizhne Olitchedayer, Podalia, Aug 22 benefactor Haifa Technion; author in field. • May 181971,42:1. 19011190211903; d. NYC, June 13 1970. See: NYTimes, Oct 17 1961, 39:3.