Porcelain from the Emma Budge Estate P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

– Der Zwischen Dem Anschluss Expressionistischer Ausdrucksformen an Zeitgenössische 100

200 유럽사회문화 제5호 Der literarische Expressionismus und und den Reihungsstil thematisiert werden, seine Medien - zweitens soll die Rolle von Cabaret, Variété und die ihnen entsprechende Revueform in ihrer Bedeutung für die performative Präsentation des Expressionismus betrachtet werden, wobei ebenfalls - drittens die Bedeutung der Geste und der Pose für das expressionistische Andreas Anglet (Köln Uni.) Drama mit dem Stummfilm als Fluchtpunkt zu erörtern ist. Eine abschließende Überlegung soll den Aporien gelten, die sich hieraus für die Auflösung des Expressionismus zu Beginn der zwanziger Jahre des letzten Jahrhunderts ergeben. Dieser Titel bedarf der Erläuterung. Im Folgenden soll nicht der Zuvor soll jedoch kurz bestimmt werden, was hier als ,Expressionismus‘ Expressionismus in seiner Rezeption und Diskussion als „Medienereignis“ bezeichnet wird. Trotz aller Probleme solcher begrifflichen Festlegungen ist ein thematisiert werden. Vielmehr wird die sich wandelnde Medienwelt zwischen Großteil der Vertreter der expressionistischen Dichtergenerationen im 1910 und 1920 als Ort der Bemühung einer jungen Generation von Dichtern deutschsprachigen Raum leicht institutionell und auch in ihren grundlegenden um Publizität, der Selbstdarstellung und entsprechend als Bezugspunkt für ihre ästhetischen Bindungen an Gruppen und Publikationsforen festzumachen.1) Innovationen betrachtet werden. Im Zentrum der folgenden Überlegungen und Neben oft einseitigen und teilweise problematischen Versuchen der Analysen sollen dabei sowohl die prägnante Thematisierung -

200 Da-Oz Medal

200 Da-Oz medal. 1933 forbidden to work due to "half-Jewish" status. dir. of Collegium Musicum. Concurr: 1945-58 dir. of orch; 1933 emigr. to U.K. with Jooss-ensemble, with which L.C. 1949 mem. fac. of Middlebury Composers' Conf, Middlebury, toured Eur. and U.S. 1934-37 prima ballerina, Teatro Com- Vt; summers 1952-56(7) fdr. and head, Tanglewood Study munale and Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Florence. 1937-39 Group, Berkshire Music Cent, Tanglewood, Mass. 1961-62 resid. in Paris. 1937-38 tours of Switz. and It. in Igor Stravin- presented concerts in Fed. Repub. Ger. 1964-67 mus. dir. of sky's L'histoire du saldai, choreographed by — Hermann Scher- Ojai Fests; 1965-68 mem. nat. policy comm, Ford Found. Con- chen and Jean Cocteau. 1940-44 solo dancer, Munic. Theater, temp. Music Proj; guest lect. at major music and acad. cents, Bern. 1945-46 tours in Switz, Neth, and U.S. with Trudy incl. Eastman Sch. of Music, Univs. Hawaii, Indiana. Oregon, Schoop. 1946-47 engagement with Heinz Rosen at Munic. also Stanford Univ. and Tanglewood. I.D.'s early dissonant, Theater, Basel. 1947 to U.S. 1947-48 dance teacher. 1949 re- polyphonic style evolved into style with clear diatonic ele- turned to Fed. Repub. Ger. 1949- mem. G.D.B.A. 1949-51 solo ments. Fel: Guggenheim (1952 and 1960); Huntington Hart- dancer, Munic. Theater, Heidelberg. 1951-56 at opera house, ford (1954-58). Mem: A.S.C.A.P; Am. Musicol. Soc; Intl. Soc. Cologne: Solo dancer, 1952 choreographer for the première of for Contemp. -

Monthly for the Promotion of Jewish Culture

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 16 09.00/09.30 Registration 09.30/10.00 Opening Notes Vice Rector Peter Riedler Dean of Studies of the Faculty of Humanities Margit Reitbauer Heads of the Institutes of Slavic Studies and Jewish Studies, Organizers 10.00/11.30 I IMPERIAL EXPERIENCES, ENTANGLEMENTS AND ENCOUNTERS KNOWLEDGE AND CULTURE THROUGH HISTORY Chair: Mirjam Rajner KARKASON, TAMIR The “Entangled Histories” of the Jewish Enlightenment in Ottoman Southeastern Europe ŠMID, KATJA Amarachi’s and Sasson’s Musar Ladino Work Sefer Darkhe ha-Adam. Between Reality and Intertextuality KEREM, YITZCHAK Albertos Nar, from Historian to Author and Ethnographer. Crossing from Salonikan Sephardic Historian to Greek Prose, Fiction, Social Commentary and Tracing Greek Influences on Salonikan and Izmir Sephardic Culture 11.30/12.00 Break 12.00/13.00 PERCEIVING THE SELF AND THE OTHER Chair: Željka Oparnica GRAZI, ALESSANDRO On the Road to Emancipation. Isacco Samuele Reggio’s Jewish and Italian Identity in 19th-century Gorizia Milovanovič, Stevan The Images of Sephardim in the Travel Book Oriente by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez 13.00/15.00 Lunch 15.00/16.30 POSTIMPERIAL EXPERIENCES Chair: Sonja Koroliov OSTAJMER, BRANKO Mavro Špicer (1862—1936) and His Views on the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy JURLINA, PETRA Small Town Elegy: Shaping and Guarding Memory in Rural Croatia. The Case of Vinica, Lepavina and Slatinski Drenovac SELVELLI, GIUSTINA The Multicultural Cities of Plovdiv and Ruse Through the Eyes of Elias Canetti and Angel Wagenstein. Two “Post-Ottoman” Jewish Writers 16.30/17.00 -

Porträts Von Tilla Durieux

© 2016, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847106340 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847006343 © 2016, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847106340 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847006343 Hannah Ripperger Porträts vonTilla Durieux Bildnerische Inszenierung einesTheaterstars Mit 24 Abbildungen V&Runipress © 2016, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847106340 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847006343 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet þber http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-8470-0634-3 Weitere Ausgaben und Online-Angebote sind erhÐltlich unter: www.v-r.de Die Arbeit wurde im Jahr 2015 von der FakultÐt fþr Philosophie-, Kunst-, Geschichts- und Gesellschaftswissenschaften der UniversitÐt Regensburg als Dissertation angenommen. D355 Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstþtzung der Richard Stury Stiftung und der Frauenbeauftragten der FakultÐt fþr Philosophie, Kunst-, Geschichts- und Gesellschaftswissenschaften im Rahmen des Finanziellen Anreizsystems zur Fçrderung der Gleichstellung an der UniversitÐt Regensburg. 2016, V&R unipress GmbH, Robert-Bosch-Breite 6, D-37079 Gçttingen / www.v-r.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschþtzt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen FÐllen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Titelbild: Emil Orlik, Tilla Durieux als Potiphar, Bl. 6 aus der Mappe »Spielen und TrÐumen«, 1922, Radierung, 24,7 x 18,8/31,6 x 23 cm, Kunstforum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg, Inv.Nr. 19270. Foto: Kunstforum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg. © 2016, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847106340 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847006343 Inhalt Danksagung ................................. 9 I. Einleitung ............................... 11 I.1 Die »meistgemalte Frauihrer Epoche« ............. 11 I.2 Vorgehen und Fragestellung ................. -

Tilla Durieux

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Melanie Ruff Tilla Durieux Selbstbilder und Images der Schauspielerin 1 Danksagung Ich möchte an dieser Stelle folgenden Personen, die mir bei der Entstehung dieser Arbeit in unterschiedlichster Form behilflich waren, meinen Dank aussprechen. Allen voran danke ich meinen Eltern Sissi und Hubert, meinen Großeltern Angela und Franz und meinen beiden Tanten Elfi und Gabi, deren persönliche und finanzielle Unterstützung mir mein Studium erst ermöglicht haben. Für die professionelle und engagierte Betreuung meiner Arbeit danke ich Univ. Prof.in Dr.in Johanna Gehmacher, in deren DiplomandInnen- und DissertantInnenseminar ich viele Anregungen und wertvolle Hilfestellungen erfahren habe. Daran anknüpfend möchte ich mich auch bei meinen KollegInnen aus dem Seminar bedanken. Die Anregungen und Ideen haben mich immer wieder zum weiterdenken angeregt und mir neue Wege aufgezeigt. Meinen besonderen Dank möchte ich meinen Freunden aussprechen, die mir mit aufmundernten Worten und fachlichen Diskussionen eine große Unterstützung waren. Bei Sabine, Simone und Elfi möchte ich nochmals für die unermüdliche und engagierte Korrektur meiner Arbeit bedanken. 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung - „Ein Leben der Überschreitungen“ 2 Tilla Durieux` Lebensdaten 3 Autobiografien als Quelle 4 Tilla Durieux` Erziehung und ihre Ausbildung zur Schauspielerin 4.1 Mädchenbildung 4.2 Mädchenschulen 4.3 Bildungsmöglichkeiten für Mädchen nach der Grundschule 4. 4 Vom Backfisch -

Information Issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain 8 Fairfax Mansions

Vol. XVII No. 1 January, 1962 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN 8 FAIRFAX MANSIONS. FiNCHLEY RD. (corner Fairlax Rd.). London, N.W.S 0//ice and Consulting Hours: Telephone: MAIda Vale 9096/7 (General Ollice and Welfare for the Aged) Mondav to Thursdav 10 am—I a m 3—6 o m MAIda Vale 4449 (Employment Agency, annually licensed by the L.C.C.. monaay lo i luirsaay lu a.m. i p.m. J o p.m. and Social Services Dept.) Friday 10 a.m.—1 p.m. ACROSS THE CHANNEL THE EICHMANN VERDICT From our Jerusalem Correspondent German Jews in France In the trial against Adolf Eichmann on 15 counts for crimes against the Jewish people, A visitor to the Central Synagogue in Paris will one hour's drive from Paris. The former dining- crimes against humanity and war crimes, the court notice in the entrance hall the memorial tablets room and lounge are now used as communal handed down its verdict: guilty on all 15 counts. where the names are inscribed of those who rooms. Most of the residents no longer work. The court arrived at its judgment after hearinis lost their lives during the Second World War as It seems that the distance from Paris does not which opened on April llth, 1961, and concluded members of the fighting forces or of the Resistance matter to them too much. They are compensated on August Mth, after 114 sessions over a period movement. Inside the synagogue the eye is drawn by the wonderful country in which they live. -

Resolved Stolen Art Claims

RESOLVED STOLEN ART CLAIMS CLAIMS FOR ART STOLEN DURING THE NAZI ERA AND WORLD WAR II, INCLUDING NAZI-LOOTED ART AND TROPHY ART* DATE OF RETURN/ CLAIM CLAIM COUNTRY† RESOLUTION MADE BY RECEIVED BY ARTWORK(S) MODE ‡ Australia 2000 Heirs of Johnny van Painting No Litigation Federico Gentili Haeften, British by Cornelius Bega - Monetary di Giuseppe gallery owner settlement1 who sold the painting to Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide Australia 05/29/2014 Heirs of The National Painting No Litigation - Richard Gallery of “Head of a Man” Return - Semmel Victoria previously attributed Painting to Vincent van Gogh remains in museum on 12- month loan2 * This chart was compiled by the law firm of Herrick, Feinstein LLP from information derived from published news articles and services available mainly in the United States or on the Internet, as well as law journal articles, press releases, and other sources, consulted as of August 6, 2015. As a result, Herrick, Feinstein LLP makes no representations as to the accuracy of any of the information contained in the chart, and the chart necessarily omits resolved claims about which information is not readily available from these sources. Information about any additional claims or corrections to the material presented here would be greatly appreciated and may be sent to the Art Law Group, Herrick, Feinstein LLP, 2 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10016, USA, by fax to +1 (212) 592- 1500, or via email to: [email protected]. Please be sure to include a copy of or reference to the source material from which the information is derived. -

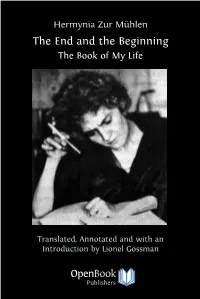

The End and the Beginning the Book of My Life

Hermynia Zur Mühlen The End and the Beginning The Book of My Life Translated, Annotated and with an Introduction by Lionel Gossman OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/65 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Hermynia Zur Mühlen in the garden of the estate at Eigstfer, Estonia, c. 1910. The End and the Beginning The Book of My Life by Hermynia Zur Mühlen with Notes and a Tribute by Lionel Gossman ORIGINALLY TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY FRANK BARNES AS THE RUNAWAY COUNTESS (NEW YORK: JONATHAN CAPE & HARRISON SMITH, 1930). TRANSLATION EXTENSIVELY CORRECTED AND REVISED FOR THIS NEW EDITION BY LIONEL GOSSMAN. Cambridge 2010 Open Book Publishers CIC Ltd., 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com @ 2010 Lionel Gossman Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Details of allowances and restrictions are available at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website: http://www.openbookpublishers.com ISBN Hardback: 978-1-906924-28-7 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-906924-27-0 ISBN Digital (pdf): 978-1-906924-29-4 Acknowledgment is made to the following for generously permitting use of material in their possession: Princeton University Library, Michael Stumpp, Director of the Emil Stumpp Archiv, Gelnausen, Louise Pettus Archives and Special Collections, Winthrop University Germany and Dr. -

Biografia Lexikon Österreichischer Frauen

Ilse Korotin (Hg.) biografiA. Lexikon österreichischer Frauen Band 4 Register 2016 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Veröffentlicht mit der Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund ( FWF ): PUB 162-V15 sowie durch das Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Wirtschaft und das Bundesministerium für Bildung und Frauen Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://portal.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2016 by Böhlau Verlag Ges. m. b. H & Co. KG , Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Layout: Carolin Noack, Ulrike Dietmayer Einbandgestaltung: Michael Haderer und Anne Michalek , Wien Druck und Bindung: baltoprint, Litauen Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in the EU ISBN 978-3-205-79590 -2 Inhalt Einleitung: Frauen sichtbar machen. Das Projekt biografiA. Biografische Datenbank und Lexikon österreichischer Frauen . 7 Band 1 Biografien A – H ........................................ 19 – 1420 Band 2 Biografien I – O ......................................... 1421 – 2438 Band 3 Biografien P – Z ........................................ 2439 – 3666 Band 4 Register................................................... 3667– 4 24 8 Personen.............................................. -

I. Abstract J

J. Steven Schumacher Resolving Nazi-era Art Repatriation Claims in the Twenty-First Century A Note to the Reader To protect the anonymity of this project’s subject, certain details including some names, dates, locations, etc. have been altered. Additionally, subject-specific citations have been omitted. I. Abstract J. Steven Schumacher, “Resolving Nazi-era Art Repatriation Claims in the Twenty-First Century,” Legal Studies Senior Honors Thesis (2013) When the Nazi government came to power in 1933, a cataclysmic chain of events were set into motion that would eventually generate global turmoil and leave millions dead. An unexpected casualty of this horrific era was the displacement of huge volumes of art seized from European Jews that were either sold to enrich Nazi coffers or handed to Nazi elites. After Germany’s surrender in 1945, Europe was in ruins and among those rebuilding their lives were Jews who escaped Hitler’s Final Solution. For some of these individuals and their families, this process eventually included asserting their rights to property stolen from them. Among those property claims, arguably the most complex, high stakes, and rigorously contested have pertained to fine art. Even in the twenty-first century, art-based repatriation claims continue to be waged by the next generation of Holocaust survivors on behalf of deceased relatives. Often such claims present current owners – both private collectors and public institutions – with huge financial liabilities and the potential diminution of esteemed collections. This project explores the legal complexities and psychological dynamics experienced by Nazi-era art repatriation claimants and their attorneys through both scholarly and field research. -

Flucht Durch Europa. Schauspielerinnen Im Exil 1933-1945

Flucht durch Europa Schauspielerinnen im Exil 1933-1945 Augen-Blick 33 Marburg 2002 AUGEN-BLICK MARBURGER HEFTE ZUR MEDIENWISSENSCHAFT Eine Veröffentlichung des Instituts für Neuere deutsche Literatur und Medien im Fachbereich 09 der Philipps-Universität-Marburg Heft 33 November 2002 Herausgegeben von Jürgen Felix Günter Giesenfeld Heinz-B. Heller Knut Hickethier Thomas Koebner Karl Prümm Wilhelm Solms Guntram Vogt Redaktion: Günter Giesenfeld Redaktionsanschrift: Institut für Neuere deutsche Literatur und Medien Wilhelm-Röpke-Straße 6A, 35039 Marburg, Tel. 06421/284657 Verlag: Schüren-Presseverlag, Deutschhausstraße 31, 35037 Marburg Einzelheft DM 10.00 (ÖS 77/SFr 8.50); Jahresabonnement (2 Hefte) DM 20.-- (ÖS 136/SFr 16.--) Bestellungen an den Verlag. Anzeigenverwaltung: Schüren Presseverlag © Schüren Presseverlag, alle Rechte vorbehalten Umschlaggestaltung: Uli Prugger, Gruppe GUT Druck: WB-Druck, Rieden ISSN 0179-2555 ISBN 3-89472-036-0 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort..........................................................................................5 Christina Jung Moskau mit einem Lächeln. Annäherung an die Schauspielerin Lotte Loebinger und das sowjetische Exil ................................9 Sandra Zimmermann Fluchtpunkt England ..............................................................39 Astrid Pohl Salomé auf der Flucht. Tilla Durieux und das Exil deutschsprachiger Schauspielerinnen in der Schweiz ..........................................71 Gaby Styn Auf dem weißen Rößl zum Alexanderplatz Camilla Spira und ihre Schwester -

Salomé Auf Der Flucht. Tilla Durieux Und Das Exil Deutschsprachiger Schauspielerinnen in Der Schweiz 2002

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Astrid Pohl Salomé auf der Flucht. Tilla Durieux und das Exil deutschsprachiger Schauspielerinnen in der Schweiz 2002 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1514 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Pohl, Astrid: Salomé auf der Flucht. Tilla Durieux und das Exil deutschsprachiger Schauspielerinnen in der Schweiz. In: Augen-Blick. Marburger Hefte zur Medienwissenschaft. Heft 33: Flucht durch Europa. Schauspielerinnen im Exil 1933-1945 (2002), S. 71–107. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1514. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above.