Islam in Christian Tolerance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Rebellion, and Arab Muslim Slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Race, rebellion, and Arab Muslim slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E. Nicholas C. McLeod University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, History of Religion Commons, Islamic Studies Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation McLeod, Nicholas C., "Race, rebellion, and Arab Muslim slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2381. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2381 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, REBELLION, AND ARAB MUSLIM SLAVERY: THE ZANJ REBELLION IN IRAQ, 869 - 883 C.E. By Nicholas C. McLeod B.A., Bucknell University, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In Pan-African Studies Department of Pan-African Studies University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Nicholas C. -

Al-Nahl Volume 13 Number 3

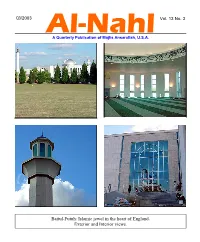

Q3/2003 Vol. 13 No. 3 Al-Nahl A Quarterly Publication of Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. Baitul-Futuh: Islamic jewel in the heart of England. Exterior and Interior views. Special Issue of the Al-Nahl on the Life of Hadrat Dr. Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, radiyallahu ‘anhu. 60 pages, $2. Special Issue on Dr. Abdus Salam. 220 pages, 42 color and B&W pictures, $3. Ansar Ansar (Ansarullah News) is published monthly by Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. and is sent free of charge to all Ansar in the U.S. Ordering Information: Send a check or money order in the indicated amount along with your order to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905. Price includes shipping and handling within the continental U.S. Conditions of Bai‘at, Pocket-Size Edition Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. has published the ten conditions of initiation into the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in pocket size brochure. Contact your local officials for a free copy or write to Ansar Publications, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring MD 20905. Razzaq and Farida A story for children written by Dr. Yusef A. Lateef. Children and new Muslims, all can read and enjoy this story. It makes a great gift for the children of Ahmadi, Non-Ahmadi and Non- Muslim relatives, friends and acquaintances. The book contains colorful drawings. Please send $1.50 per copy to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905 with your mailing address and phone number. Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. will pay the postage and handling within the continental U.S. -

The Review of Religions, May 1988

THE REVIEW of RELIGIONS VOL LXXXIII NO. 5 MAY 1988 IN THIS ISSUE EDITORIAL GUIDE POSTS • SOURCES OF SIRAT • PRESS RELEASE • PERSECUTION IN PAKISTAN • ISLAM AND RUSSIA • BLISS OF KHILAFAT > EIGHTY YEARS AGO MASJID AL-AQSA THE AHMADIYYA MOVEMENT The Ahmadiyya Movement was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the expected world reformer and the Promissed Messiah whose advent had been foretold by the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be on him). The Movement is an embodiment of true and real Islam. It seeks to unite mankind with its Creator and to establish peace throughout the world. The present head of the Movement is Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. The Ahm-adiyya Movement has its headquarters at Rabwah, Pakistan, and is actively engaged in missionary work. EDITOR: BASHIR AHMAD ORCHARD ASSISTANT EDITOR: NAEEM OSMAN MEMON MANAGING EDITOR: AMATUL M. CHAUDHARY EDITORIAL BOARD B. A. RAFIQ (Chairman) A. M. RASHED M. A. SAQI The REVIEW of RELIGIONS A monthly magazine devoted to the dissemination of the teachings of Islam, the discussion of Islamic affairs and religion in general. \f The Review of Religions is an organ of the Ahmadiyya CONTENTS Page Movement which represents the pure and true Islam. It is open to all for discussing 1. Editorial 2 problems connected with the religious and spiritual 2. Guide Posts 3 growth of man, but it does (Bashir Ahmad Orchard) not accept responsibility for views expressed by 3. Sources of Sirat contributors. (Hazrat Mirza Bashir Ahmad) 4. Press Release 15 All correspondence should (Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry)' be forwarded directly to: 5. Persecution in Pakistan 16 The Editor, (Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry) The London Mosque, 16 Gressenhall Road, 6. -

Review of Religions Centenary Message from Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih IV

Contents November 2002, Vol.97, No.11 Centenary Message from Hadhrat Ameerul Momineen . 2 Editorial – Mansoor Shah . 3 Review of Religions: A 100 Year History of the Magazine . 7 A yearning to propogate the truth on an interntional scale. 7 Revelation concerning a great revolution in western countries . 8 A magazine for Europe and America . 9 The decision to publish the Review of Religions . 11 Ciculation of the magazine . 14 A unique sign of the holy spirit and spiritual guidance of the Messiah of the age. 14 Promised Messiah’s(as) moving message to the faithful members of the Community . 15 The First Golden Phase: January 1902-May 1908. 19 The Second Phase; May 1908-March 1914 . 28 Third Phase: March 1914-1947 . 32 The Fourth Phase: December 1951-November 1965. 46 The Fifth Phase: November 1965- June 1982 . 48 The Sixth Phase: June 1982-2002 . 48 Management and Board of Editors. 52 The Revolutionary articles by Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. 56 Bright Future. 58 Unity v. Trinity – part II - The Divinity of Jesus (as) considered with reference to the extent of his mission - Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as) . 60 Chief Editor and Manager Chairman of the Management Board Mansoor Ahmed Shah Naseer Ahmad Qamar Basit Ahmad. Bockarie Tommy Kallon Special contributors: All correspondence should Daud Mahmood Khan Amatul-Hadi Ahmad be forwarded directly to: Farina Qureshi Fareed Ahmad The Editor Fazal Ahmad Proof-reader: Review of Religions Shaukia Mir Fauzia Bajwa The London Mosque Mansoor Saqi Design and layout: 16 Gressenhall Road Mahmood Hanif Tanveer Khokhar London, SW18 5QL Mansoora Hyder-Muneeb United Kingdom Navida Shahid Publisher: Al Shirkatul Islamiyyah © Islamic Publications, 2002 Sarah Waseem ISSN No: 0034-6721 Saleem Ahmad Malik Distribution: Tanveer Khokhar Muhammad Hanif Views expressed in this publication are not necessarily the opinions of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. -

Truth About the Split

Truth about the Split By Hadrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad Khalifatul Masih IIra ISLAM INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATIONS LTD. Truth about the Split by Hadrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra © Islam International Publications Ltd. First English Edition 1924 Second English Edition 1938 Third English Edition 1965 Present Edition 2007 Published by: Islam International Publications Ltd. 'Islamabad' Sheephatch Lane, Tilford, Surrey GU10 2AQ, United Kingdom. Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc ISBN: 1 85372 972 8 ABOUT THE AUTHOR The Promised sonra of the Promised Messiah and Mahdias; the manifest Sign of Allah, the Almighty; the Word of God whose advent was prophesied by the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa and the Promised Messiahas as well as the past Prophets; a Star in the spiritual firmament for the like of which the world has to wait for hundreds of years to appear; the man of God, crowned with a spiritual hallo from which radiated such scintillating rays of light as would instil spiritual life into his followers and captivate and enthral those who were not fortunate to follow him; an orator of such phenomenal quality that his speeches would make his audience stay put for hours on end, come rain or shine, deep into the late hours of the evenings while words flowed from his tongue like honey dripping into their ears to reach the depths of their soul to fill them with knowledge and invigorate their faith; the ocean of Divine and secular knowledge; the Voice Articulate of the age; without doubt the greatest genius of the 20th century; a man of phenomenal intelligence and memory; an epitome of the qualities of leadership; the one whose versatility cannot be comprehended—Hadrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra (1889-1965), Muslih Ma‘ud (the Promised Reformer) was the eldest son and the second successor (Khalifa) of the Promised Messiahas. -

Mr Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen I Deem It an Honour to Be Addressing the Jalsa Salana on a Subject That Will Give a Glimpse In

Mr Chairman, ladies and gentlemen I deem it an honour to be addressing the Jalsa Salana on a subject that will give a glimpse into the pure character of the Imam of this age. A life modelled on the example of his master the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw). The translation of the 9th verse of Sura Maidah that I recited is; ‘O ye who believe! Be steadfast in the cause of Allah, bearing witness in equity and let not a peoples’ enmity incite you to act otherwise than with justice. Be always just, that is nearer to righteousness. And fear Allah. Surely Allah is well aware of what you do.’ The other is from sura Yasin verse 31; ‘Alas for My servants! There comes not a Messenger but they mock at him’. History bears witness that this indeed forms part of the life of every Messenger of God The Holy Prophet (saw), was known as Al Ameen by the Meccans but as soon as he made his claim, he was met with ridicule and persecution from those very same people. The Promised Messiah (as) , prior to his claim was championed as the saviour of Islam, but no sooner under Divine command had he made his claim that he too faced bitter opposition. He always displayed patience, sympathy and kindness to those who opposed him, this is the subject I must speak on today. Today we live in a world filled with hate, violence and rancour. The incidents of the Promised Messiah (as) kindness even to his opponents are a lesson for humanity. -

Jul-Sep 2013

From the Editor... uly 25th 1913 was that memorable date in which Jama’at Ahmadiyya Meet the Team... Jwas first brought to the UK by Missionary Hazrat Chadhry Fateh Muhammad Sial Sahibra. 2013 marks the centenary of that joyous MARYAM EDITOR occasion. Munazza Khan EDITORIAL BOARD A historic address by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaba at the Houses of Hibba-Tul Mussawir Parliament is a key celebration that recently took place in the UK Hina Rehman to mark the successful 100 years of the establishment of Jama’at Maleeha Mansur Ahmadiyya in the UK. Among other celebrations that have been Meliha Hayat taking place across the country are charity walks and family picnics. Ramsha Hassan Salma Manahil Tahir A section of this magazine has been devoted to mark this special and joyous occasion. Readers can join in with the celebrations as we share MANAGER an exclusive article by respected Sadr Sahiba Lajna Imaillah UK, along Zanubia Ahmad with the Jama’at’s history in a timeline of major events. ASSISTANT MANAGER Alhamdolillah, the Jama’at has seen much progress in the propogation Dure Jamal Mala of Ahmadiyyat, the true Islam, since 1913. Last year, almost half a COVER DESIGN million poeple entered into the folds of Ahmadiyyat at the hands of our Atiyya Wasee beloved Huzur, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaba, at the 46th International Jalsa Salana UK. With the next Annual Convention coming up in PAGE DESIGN August, we all anticipate this number to rise with the help of Allah. Soumbal Qureshi Nabila Sosan Thus, God’s promise to all Muslims through the founder of Islam, The Holy Prophetsaw, of safeguarding the message of Islam through Khilafat ARABIC TYPING continues to be fulfilled, presently through unity at the hands of the Safina Nabeel Maham Khalifa-e-Waqt, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaba, who has repeatedly stated to world leaders that it is only at the hands of Khilafat that PRINTED BY Raqeem Press, Tilford UK humanity can be united. -

Light and ISLAMIC REVIEW Exponent of Islam and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for Over Eighty Years April – June 2005

“Call to the path of thy Lord with wisdom and goodly exhortation, and argue with people in the best manner.” (Holy Quran, 16:125) The Light AND ISLAMIC REVIEW Exponent of Islam and the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for over eighty years April – June 2005 In the spirit of the above-cited verse, this periodical attempts to dispel misunderstandings about the religion of Islam and endeavors to facilitate inter-faith dialogue based on reason and rationality. Vol. 82 CONTENTS No. 2 Dutch Holy Quran Opening Speech . .3 By Dr. Noman Malik Human Rights in Islam . .7 By Dr. Ayesha Saliha Khan A Commentary on Mirza Masroor Ahmad’s khutba dealing with the “ever-lasting” Qadiani khilafat . .13 By Dr. Zahid Aziz Certainty In Faith . .17 By Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Published on the World-Wide Web at: www.muslim.org ◆ Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam Lahore Inc., U.S.A. ◆ P.O. Box 3370, Dublin, Ohio 43016, U.S.A. 2 THE LIGHT AND ISLAMIC REVIEW ■ APRIL – JUNE 2005 The Light was founded in 1921 as the organ of the AHMADIYYA ANJUMAN ISHA‘AT ISLAM (Ahmadiyya Association for the Propagation of Islam) of About ourselves Lahore, Pakistan. The Islamic Review was published in England from 1913 for over 50 years, and in the U.S.A. from 1980 to 1991. The present Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam Lahore periodical represents the beliefs of the worldwide branches of the has branches in many countries including: Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam, Lahore. U.S.A. Australia ISSN: 1060–4596 U.K. Canada Holland Fiji Editorial Board: Directors of AAIIL, Inc., USA Indonesia Germany Suriname India Circulation: Mrs. -

Masterscriptie Tycho Hofstra Master Cultuurgeschiedenis Faculteit Der

Masterscriptie Tycho Hofstra Master Cultuurgeschiedenis Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen, Universiteit van Amsterdam Begeleider: dr. J.C. van Zanten Tweede lezer: dr. J.J.B. Turpijn Amsterdam, juni 2016 Afbeelding omgslag v.l.n.r: R. Fruin, J. Huizinga, A.A. van Schelven, E.H. Kossmann Tweede rij v.l.n.r: G.W. Kernkamp, J.M. Romein, C.H.Th. Bussemaker, J.C. Boogman Derde rij v.l.n.r: G.J. Presser, P.J Blok, P.C.A. Geyl, A. Goslinga Inhoudsopgave Inleiding ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1. De grondslag van Fruin (1860-1894) .................................................................................. 7 1.1 Fruin .................................................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Blok ................................................................................................................................ 11 2. De crisis van de hulpwetenschappen (1865-1890) ........................................................... 16 2.1 Jorissen ........................................................................................................................... 16 2.2 Wijnne ............................................................................................................................ 17 2.3 Rogge .............................................................................................................................. 19 3. Stabilisatie in staatsgeschiedenis -

The Review of Religions, March 1990

VOL. LXXXV N0.3 MARCH 1990 IN THIS ISSUE • EDITORIAL • FRIDA Y SERMON • STATEMENT ON SALMAN RUSHDIE • GURU NANAK AND SIKH RELIGION • 80 YEARS AGO • ISLAM AND THE COMMUNIST WORLD • PRESS REPORT • REASON IN RELIGION > CONTACT WITH DEPARTED SOULS BELIEF IN THE UNSEEN THE AHMADIYYA MOVEMENT The Ahmadiyya Movement was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the expected world reformer and the Promissed Messiah whose advent had been foretold by the Holy Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him. The Movement is an embodiment of true and real Islam. It seeks to unite mankind with its Creator and to establish peace throughout the world. The present head of the Movement is Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. The Ahmadiyya Movement has its headquarters at Rabwah, Pakistan, and is actively engaged in missionary work. Editorial Board: B. A. Rafiq (Chairman) B. A. Orchard M. A. Shah M. A. Saqi A. M. Rushed Amtul M. Chaudhry JOINT EDITORS: BASHIR AHMAD ORCHARD MANSOOR AHMAD SHAH ASSISTANT EDITOR: NAEEM OSMAN MEMON MANAGING EDITOR: AMTUL M. CHAUDHARY The REVIEW of RELIGIONS A monthly magazine devoted to the dissemination of the teachings of Islam, the discussion of Islamic affairs and religion in general. The Review of Religions is an organ of the Ahmadiyya Movement which represents the pure and true Islam. It is open to all for discussing problems connected with the CONTENTS PAGE NO. religious and spiritual growth of man, but it does 1. Editorial. 2 not accept responsibility for views expressed by 2. Friday Sermon. 3 contributors. 3. Statement on Salman Rushdie. 7 All correspondence should 4. -

Whose Golden Age? on a Term That's Not Fit for Purpose. Tom Van Der Molen

Whose Golden Age? On A Term That's Not Fit For Purpose. Tom van der Molen In the Netherlands, the term Golden Age is widely used to refer to the period that roughly coincides with the seventeenth century. At that time the Republic of the Seven United Provinces was an economic and military world power. The term Golden Age became fashionable during the nineteenth century, when history was put into a nationalist context and the country had to unite, particularly around pride in heroes and supposed boom times. Now, two centuries later, that pride is fiercely criticized. Nineteenth-century monuments and street names that put this period and its heroes on a pedestal are being attacked. Even though it's subject to criticism, the term Golden Age is meanwhile still being used, including by the museum where I work as a curator—the Amsterdam Museum. We use that term routinely, primarily because it's become so embedded that everyone seems to understand what it's about. The term has a long history, however, and consequently a variety of associations. It's time to explore those associations and ask why we still use the term. And whether that's still a good idea. My Golden Age I'm an art historian specializing in seventeenth-century painting. My job in the Amsterdam Museum has exposed me to subjects far from art and far from that century, but my base remains Amsterdam, painting and the seventeenth century. I used the term ‘Golden Age’ all the time myself. It was the name of courses I took as a student; I came across the term in books and exhibitions and was never challenged to review it critically. -

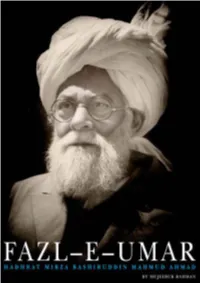

Fazl-E-Umar.Pdf

FAZL-E-UMAR The Life of Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad Khalifatul Masih II [ra] First published in the UK in 2012 by Islam International Publications Copyright © Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK 2012 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. For legal purposes the Copyright Acknowledgements constitute a continuation of this copyright page. ISBN: 978-0-85525-995-2 Designed and distributed by Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK Author: Mujeebur Rahman Printed and bound by Polestar UK Print Limited CONTENTS Letter from Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad [atba] 1 Foreword 3 Comments by Sadr Majlis Khuddamul Ahmadiyya UK 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 9 PART 1 15 Early childhood and parental training 17 Education 41 Public speaking and writing 55 Childhood interests, games and pastimes 63 Circle of contacts 75 Belief in the truth of his father and its consequences 80 Ever–growing faith in the Promised Messiah [as] 88 The death and burial of the Promised Messiah [as] 90 Historic pledge of Hadhrat Sahibzada Mirza Mahmud Ahmad 98 PART 2 103 Establishment of Khilafat in the Ahmadiyya Movement 105 Efforts to support and strengthen the institution of Khilafat 110 PART 3 143 Khilafat of Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad [ra] 144 Independence