Ahmadi Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musleh Maud: the Promised Reformer

PROPHECY OF MUSLEH MAUD: THE PROMISED REFORMER REF: FRIDAY SERMON (20.2.15) Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad as (1835-1908) The Promised Messiah and Imam Mahdi 1) Hadhrat Al-Haaj Maulana Hakeem Nooruddin Khalifatul Masih I (ra) 2) Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmood Ahmad First Successor to the Promised Messiah (as) “Musleh Maud“(ra) Period of Khilafat: 1908-1914 Khalifatul Masih II Second Successor to the Promised Messiah. (as) Period of Khilafat: 1914 –1965 3) Hadhrat Mirza Nasir Ahmad Khalifatul Masih III (rh) 4) Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad Third Successor to the Promised Messiah (as) Khalifatul Masih IV(rh) Period of Khilafat: 1965-1982 Fourth Successor to the Promised Messiah (as) Period of Khilafat: 1982 - 2003 5) Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad Khalifatul Masih V (aba) Fifth Successor to the Promised Messiah (as) Period of Khilafat: 2003- present day . KHALIFATUL MASIH II Name: Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmood Ahmad Musleh Maud Khalifatul Masih II Second Successor to the Promised Messiah (ra) Date of Birth: January 12th 1889 Period of Khilafat: 1914 –1965 He was 25 years of age when he became Khalifa Passed Away: On November 8, 1965 Musleh Maud: 28th Jan 1944 – claimed to be the Promised Son ‘Musleh Maud’ (The Promised Reformer) Photographs of Khalifatul Masih II (ra) PROPHECY OF MUSLEH MAUD Hadhrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmood Ahmad (ra) was the second successor of the Promised Messiah (as). He was a distinguished (great) Khalifa because his birth was foretold by a number of previous Prophets and Saints. The Promised Messiah (as) received a Divine sign for the truth of Islam as a result of his forty days of prayer at Hoshiarpur (India). -

Race, Rebellion, and Arab Muslim Slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Race, rebellion, and Arab Muslim slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E. Nicholas C. McLeod University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, History of Religion Commons, Islamic Studies Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation McLeod, Nicholas C., "Race, rebellion, and Arab Muslim slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2381. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2381 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, REBELLION, AND ARAB MUSLIM SLAVERY: THE ZANJ REBELLION IN IRAQ, 869 - 883 C.E. By Nicholas C. McLeod B.A., Bucknell University, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In Pan-African Studies Department of Pan-African Studies University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Nicholas C. -

Islamist Politics in South Asia After the Arab Spring: Parties and Their Proxies Working With—And Against—The State

RETHINKING POLITICAL ISLAM SERIES August 2015 Islamist politics in South Asia after the Arab Spring: Parties and their proxies working with—and against—the state WORKING PAPER Matthew J. Nelson, SOAS, University of London SUMMARY: Mainstream Islamist parties in Pakistan such as the Jama’at-e Islami and the Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Islam have demonstrated a tendency to combine the gradualism of Brotherhood-style electoral politics with dawa (missionary) activities and, at times, support for proxy militancy. As a result, Pakistani Islamists wield significant ideological influence in Pakistan, even as their electoral success remains limited. About this Series: The Rethinking Political Islam series is an innovative effort to understand how the developments following the Arab uprisings have shaped—and in some cases altered—the strategies, agendas, and self-conceptions of Islamist movements throughout the Muslim world. The project engages scholars of political Islam through in-depth research and dialogue to provide a systematic, cross-country comparison of the trajectory of political Islam in 12 key countries: Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Syria, Jordan, Libya, Pakistan, as well as Malaysia and Indonesia. This is accomplished through three stages: A working paper for each country, produced by an author who has conducted on-the-ground research and engaged with the relevant Islamist actors. A reaction essay in which authors reflect on and respond to the other country cases. A final draft incorporating the insights gleaned from the months of dialogue and discussion. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. -

Al-Nahl Volume 13 Number 3

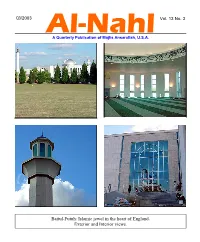

Q3/2003 Vol. 13 No. 3 Al-Nahl A Quarterly Publication of Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. Baitul-Futuh: Islamic jewel in the heart of England. Exterior and Interior views. Special Issue of the Al-Nahl on the Life of Hadrat Dr. Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, radiyallahu ‘anhu. 60 pages, $2. Special Issue on Dr. Abdus Salam. 220 pages, 42 color and B&W pictures, $3. Ansar Ansar (Ansarullah News) is published monthly by Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. and is sent free of charge to all Ansar in the U.S. Ordering Information: Send a check or money order in the indicated amount along with your order to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905. Price includes shipping and handling within the continental U.S. Conditions of Bai‘at, Pocket-Size Edition Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. has published the ten conditions of initiation into the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in pocket size brochure. Contact your local officials for a free copy or write to Ansar Publications, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring MD 20905. Razzaq and Farida A story for children written by Dr. Yusef A. Lateef. Children and new Muslims, all can read and enjoy this story. It makes a great gift for the children of Ahmadi, Non-Ahmadi and Non- Muslim relatives, friends and acquaintances. The book contains colorful drawings. Please send $1.50 per copy to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905 with your mailing address and phone number. Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. will pay the postage and handling within the continental U.S. -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

The Review of Religions, May 1988

THE REVIEW of RELIGIONS VOL LXXXIII NO. 5 MAY 1988 IN THIS ISSUE EDITORIAL GUIDE POSTS • SOURCES OF SIRAT • PRESS RELEASE • PERSECUTION IN PAKISTAN • ISLAM AND RUSSIA • BLISS OF KHILAFAT > EIGHTY YEARS AGO MASJID AL-AQSA THE AHMADIYYA MOVEMENT The Ahmadiyya Movement was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the expected world reformer and the Promissed Messiah whose advent had been foretold by the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be on him). The Movement is an embodiment of true and real Islam. It seeks to unite mankind with its Creator and to establish peace throughout the world. The present head of the Movement is Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. The Ahm-adiyya Movement has its headquarters at Rabwah, Pakistan, and is actively engaged in missionary work. EDITOR: BASHIR AHMAD ORCHARD ASSISTANT EDITOR: NAEEM OSMAN MEMON MANAGING EDITOR: AMATUL M. CHAUDHARY EDITORIAL BOARD B. A. RAFIQ (Chairman) A. M. RASHED M. A. SAQI The REVIEW of RELIGIONS A monthly magazine devoted to the dissemination of the teachings of Islam, the discussion of Islamic affairs and religion in general. \f The Review of Religions is an organ of the Ahmadiyya CONTENTS Page Movement which represents the pure and true Islam. It is open to all for discussing 1. Editorial 2 problems connected with the religious and spiritual 2. Guide Posts 3 growth of man, but it does (Bashir Ahmad Orchard) not accept responsibility for views expressed by 3. Sources of Sirat contributors. (Hazrat Mirza Bashir Ahmad) 4. Press Release 15 All correspondence should (Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry)' be forwarded directly to: 5. Persecution in Pakistan 16 The Editor, (Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry) The London Mosque, 16 Gressenhall Road, 6. -

Review of Religions Centenary Message from Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih IV

Contents November 2002, Vol.97, No.11 Centenary Message from Hadhrat Ameerul Momineen . 2 Editorial – Mansoor Shah . 3 Review of Religions: A 100 Year History of the Magazine . 7 A yearning to propogate the truth on an interntional scale. 7 Revelation concerning a great revolution in western countries . 8 A magazine for Europe and America . 9 The decision to publish the Review of Religions . 11 Ciculation of the magazine . 14 A unique sign of the holy spirit and spiritual guidance of the Messiah of the age. 14 Promised Messiah’s(as) moving message to the faithful members of the Community . 15 The First Golden Phase: January 1902-May 1908. 19 The Second Phase; May 1908-March 1914 . 28 Third Phase: March 1914-1947 . 32 The Fourth Phase: December 1951-November 1965. 46 The Fifth Phase: November 1965- June 1982 . 48 The Sixth Phase: June 1982-2002 . 48 Management and Board of Editors. 52 The Revolutionary articles by Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. 56 Bright Future. 58 Unity v. Trinity – part II - The Divinity of Jesus (as) considered with reference to the extent of his mission - Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as) . 60 Chief Editor and Manager Chairman of the Management Board Mansoor Ahmed Shah Naseer Ahmad Qamar Basit Ahmad. Bockarie Tommy Kallon Special contributors: All correspondence should Daud Mahmood Khan Amatul-Hadi Ahmad be forwarded directly to: Farina Qureshi Fareed Ahmad The Editor Fazal Ahmad Proof-reader: Review of Religions Shaukia Mir Fauzia Bajwa The London Mosque Mansoor Saqi Design and layout: 16 Gressenhall Road Mahmood Hanif Tanveer Khokhar London, SW18 5QL Mansoora Hyder-Muneeb United Kingdom Navida Shahid Publisher: Al Shirkatul Islamiyyah © Islamic Publications, 2002 Sarah Waseem ISSN No: 0034-6721 Saleem Ahmad Malik Distribution: Tanveer Khokhar Muhammad Hanif Views expressed in this publication are not necessarily the opinions of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. -

Ansar Handbook

Aims and Objectives of Majlis Responsibilities Ansārullāh Ansār Calendar of a Nāsir Responsibilities Annual Plans of Local ‘Āmila Responsibilities Responsibilities of a Regional of a Qā'id Nā'zim Responsibilities Ansar of a Za’īm Publications Ijtīma' Shūrā Information Information Contact Education Information Syllabus The 2010 Handbook of Majlis Ansārullāh USA Sadr: Dr. Wajeeh Bajwa http://www.ansarusa.org This Page Intentionally Left Blank Majlis Ansārullāh, USA 2010 Page 2 Table of Contents Aims and Objectives of Majlis Ansārullāh ................................................................................................... 5 Foreword ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Ansār Calendar 2010 ................................................................................................................................... 14 Contact Information .................................................................................................................................... 15 National ‘Āmila of Majlis Ansārullāh USA ......................................................................................... 15 Regional Nāzimeen .............................................................................................................................. 16 Zo’ama ................................................................................................................................................. 17 Plans and -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

„Marzy Mi Się Lew Boży”. Kryzys Ustrojowy W Pakistanie 1953–1955

Dzieje Najnowsze, Rocznik L – 2018, 1 PL ISSN 0419–8824 Tomasz Flasiński Instytut Historii Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Warszawie „Marzy mi się Lew Boży”. Kryzys ustrojowy w Pakistanie 1953–1955 Abstrakt: Artykuł omawia przesilenie ustrojowe w Pakistanie, które trwało w latach 1953– 1955 i zakończyło się praktyczną likwidacją ustroju demokratycznego w tym państwie. Wła- dza wykonawcza (gubernator generalny) w sojuszu z sądowniczą (Sąd Najwyższy) i wojskiem odrzuciła przejęte po Brytyjczykach niepisane zasady regulujące parlamentaryzm, a w końcu rozpędziła i sam parlament. W ostatecznym rozrachunku droga ta powiodła kraj ku autokracji. S ł owa kluczowe: Pakistan, system westminsterski, Hans Kelsen. Abstract: The article describes the crisis of Pakistani policy between 1953 and 1955, which resulted de facto in the liquidation of democracy. The executive power (Governor-General) allied with the judicial one (Supreme Court) and the army to get rid of the unwritten princi- ples, taken over from the British, regulating the parliamentary order, and fi nally dissolved the Parliament itself. Ultimately, it led the country to autocracy. Keywords: Pakistan, Westminster system, Hans Kelsen. 12 VII 1967 r. do willi Mohammada Ayuba Khana w górskim kurorcie Murree przyszedł na kolację Muhammad Munir. Pierwszy z wymienionych, od dziewięciu lat – dokładniej od 27 X 1958 r., gdy obalił swego poprzed- nika Iskandra Mirzę – sprawujący dyktatorską władzę nad Pakistanem, powoli tracił w kraju mir po niedawnej, przegranej wojnie z Indiami; drugi, w 1962 r. minister prawa w jego rządzie, a przedtem (1954–1960) prezes Sądu Najwyższego, był już politycznym emerytem, gnębionym przez choroby. Konwersacja zeszła na temat, o którym w tej sytuacji obaj panowie mogli już rozmawiać zupełnie szczerze: zamach stanu Iskandra Mirzy, który 8 X 1958 r. -

35 Ahmadiyya

Malaysian Journal of International Relations, Volume 6, 2018, 35-46 ISSN 2289-5043 (Print); ISSN 2600-8181 (Online) AHMADIYYA: GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF A PERSECUTED COMMUNITY Abdul Rashid Moten ABSTRACT Ahmadiyya, a group, founded in 19th century India, has suffered fierce persecution in various parts of the Muslim world where governments have declared them to be non-Muslims. Despite opposition from mainstream Muslims, the movement continued its proselytising efforts and currently boasts millions of followers worldwide. Based on the documentary sources and other scholarly writings, this paper judges the claims made by the movement's founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, analyses the consequences of the claims, and examines their proselytizing strategies. This paper found that the claims made by Mirza were not in accordance with the belief of mainstream Muslims, which led to their persecution. The reasons for their success in recruiting millions of members worldwide is to be found in their philanthropic activities, avoidance of violence and pursuit of peace inherent in their doctrine of jihad, exerting in the way of God, not by the sword but by the pen. Keywords: Ahmadiyya, jihad, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Pakistan, philanthropy INTRODUCTION The Qur’an categorically mentions that Muhammad is the last in the line of the Prophets and that no prophet will follow him. Yet, there arose several individuals who claimed prophethood in Islam. Among the first to claim Prophecy was Musailama al-Kazzab, followed by many others including Mirza Hussein Ali Nuri who took the name Bahaullah (glory of God) and formed a new religion, the Bahai faith. Many false prophets continued to raise their heads occasionally but failed to make much impact until the ascendance of the non-Muslim intellectual, economic and political forces particularly in the 19th century A.D. -

The HOPE Bulletin: September–October 2008 Bulletin

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful .......... The HOPE Bulletin ……….. HU ealth,U UOngoingU PU rojects,U EU ducationU (Vol. 3:3-4) Sept-October 2008 AAIIL Worldwide Edition Editor: Akbar Abdullah CALIFORNIA JAMA‘AT PROJECT: APPROVED BY THE CENTRAL ANJUMAN, LAHORE INTRODUCTIONU In this edition of The HOPE Bulletin, the segment ALL ABOUT US, which carries a bio-sketch of our venerable stalwart, the late Dr. Basharat Ahmad (1876-1943), covers a large part of this magazine. We have, therefore, decided to curtail considerable material from other sections of the Bulletin to accommodate the entire article in one issue. This year, Ramadan was marked by the passing away of two brothers, Jabir Muhammad and Imam Warith Deen Mohammad, illustrious sons of the late Honourable Elijah Muhammad. Brother Jabir Muhammad was the manager of the famous World Champion Boxer Muhammad Ali, and Imam Warith Deen Mohammad was the National Leader of the larger of the two groups of the Afro-American Muslim Community. Inna Lillahe Wa Inna Ilehi Rajeoon. During Hazrat Ameer’s visit to Chicago in 2004, Br Jabir Muhammad had invited us to a sumptuous fish luncheon at a posh Mid-East/Mediterranean restaurant in Chicago. A day before that, Hazrat Ameer had had a fruitful discussion with the late Imam Warith Deen Muhammad, who had also invited us to lunch at the conclusion of the meeting. A day later, Hazrat Ameer participated in an historic dialogue, discussing matters of mutual interest with the Honourable Minister Louis Farrakhan, National Leader of the splinter group of the Afro-American Muslim Community, which was held at the latter's mansion, a fortress-like residence that was originally built for the late Honourable Elijah Muhammad.