Race, Rebellion, and Arab Muslim Slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Menu-Glendale-Dine-In--Dinner.Pdf

SCENES OF LEBANON 304 North Brand Boulevard Glendale, California 91203 818.246.7775 (phone) 818.246.6627 (fax) www.carouselrestaurant.com City of Lebanon Carousel Restaurant is designed with the intent to recreate the dining and entertainment atmosphere of the Middle East with its extensive variety of appetizers, authentic kebabs and specialties. You will be enticed with our Authentic Middle Eastern delicious blend of flavors and spices specific to the Cuisine Middle East. We cater to the pickiest of palates and provide vegetarian menus as well to make all our guests feel welcome. In the evenings, you will be enchanted Live Band with our award-winning entertainment of both singers and and Dance Show Friday & Saturday specialty dancers. Please join us for your business Evenings luncheons, family occasions or just an evening out. 9:30 pm - 1:30 am We hope you enjoy your experience here. TAKE-OUT & CATERING AVAILABLE 1 C A R O U sel S P ec I al TY M E Z as APPETIZERS Mantee (Shish Barak) Mini meat pies, oven baked and topped with a tomato yogurt sauce. 12 VG Vegan Mantee Mushrooms, spinach, quinoa topped with vegan tomato sauce & cashew milk yogurt. 13 Frri (Quail) Pan-fried quail sautéed with sumac pepper and citrus sauce. 15 Frog Legs Provençal Pan-fried frog legs with lemon juice, garlic and cilantro. 15 Filet Mignon Sautée Filet mignon diced, sautéed with onions in tomato & pepper paste. 15 Hammos Filet Sautée Hammos topped with our sautéed filet mignon. 14 Shrimp Kebab Marinated with lemon juice, garlic, cilantro and spices. -

Profesor Mualaf Jerman Sekarang Sudah Μmurtad¶

Profesor Mualaf Jerman Sudah Murtad PROFESOR MUALAF JERMAN SEKARANG SUDAH µMURTAD¶ Oleh Dr. Sami Alrabaa (penulis Kuwait Times) 05 Oct, 2008 Murtad disini maksudnya secara de facto. Sang Profesor hanya menyatakan tidak lagi percaya Muhammad eksis, tapi belum menyatakan diri murtad. Anehnya, bgm ia bisa mengucapkan Surat Fatihah 5x sehari sambil mengucapkan 'Muhamad rasulullah' kalau ia tidak pe rcaya bahwa Muhamad eksis? Surah-surah yang mengandung ajakan melakukan kekerasan, kebencian, dan diskriminasi terhadap wanita dalam Qur¶an dan Sunnah harus dilenyapkan atau dipandang sebagai hal yang hanya cocok untuk sejarah masa lampau saja jika Islam dan Muslim ingin diterima dalam masyarakat modern. Di awal bulan September 2008, media Jerman melaporkan pendapat dari Profesor Jerman ahli Islam bernama Sven (Muhammad) Kalisch, seorang mualaf yg mengajar ilmu agama Islam di Universitas Munster di Jerman. Prof. Kalisch menyatakan bahwa dia merasa sangat ragu bahwa Muhammad sang Nabi Islam itu pernah benar-benar ada. Dia juga menduga kemungkinan bahwa Muhammad dianggap Nabi hanya setelah dia mati. Prof. Sven (Muhammad) Kalisch Keberanian ahli Islam seperti Prof. Kalisch mengungkapkan pendapat patut diacungkan jempol, mengingat banyak orang lain ketakutan mengritik Islam karena segala macam intimidasi Muslim. Hampir dua tahun yang lalu, pemikiran dan kuliah Prof. Kalisch sangatlah berbeda dengan sekarang. Contohnya, pada kuliah umumnya di tanggal 16 Maret 2006, dia membela Syariah sebagai hukum Tuhan. Sewaktu aku menentang pendapatnya sambil menunjukkan ayat -ayat keji Qur¶an yang membujuk Muslim utk melakukan kekerasan, kebencian, dan diskrimina si atas wanita (silakan periksa Islam is a violent Faith / Islam adalah Agama Penuh Kekerasan. Click-Link), dia mulai gelagapan dan tidak tahu harus menjawab apa. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Contents 1 The Archaeology of Medieval Islamic Frontiers: An Introduction A. Asa Eger 3 Part I. The Western Frontiers: The Maghrib and The Mediterranean Sea 2 Ibāḍī Boundaries and Defense in the Jabal Nafūsa (Libya) Anthony J. Lauricella 31 3 Guarding a Well- Ordered Space on a Mediterranean Island Renata Holod and Tarek Kahlaoui 47 4 Conceptualizing the Islamic- Byzantine Maritime Frontier Ian Randall 80 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Part II. The SouthernNOT FOR Frontiers: DISTRIBUTION Egypt and Nubia 5 Monetization across the Nubian Border: A Hypothetical Model Giovanni R. Ruffini 105 6 The Land of Ṭarī’ and Some New Thoughts on Its Location Jana Eger 119 Part III. The Eastern Frontiers: The Caucasus and Central Asia 7 Overlapping Social and Political Boundaries: Borders of the Sasanian Empire and the Muslim Caliphate in the Caucasus Karim Alizadeh 139 8 Buddhism on the Shores of the Black Sea: The North Caucasus Frontier between the Muslims, Byzantines, and Khazars Tasha Vorderstrasse 168 9 Making Worlds at the Edge of Everywhere: Politics of Place in Medieval Armenia Kathryn J. Franklin 195 About the Authors 225 Index 229 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION vi Contents 1 In the last decade, archaeologists have increasingly The Archaeology of focused their attention on the frontiers of the Islamic Medieval Islamic Frontiers world, partly as a response to the political conflicts in central Middle Eastern lands. In response to this trend, An Introduction a session on “Islamic Frontiers and Borders in the Near East and Mediterranean” was held at the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) Annual Meet- A. Asa Eger ings, from 2011 through 2013. -

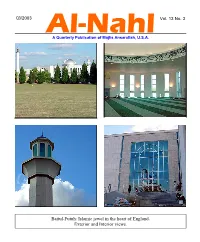

Al-Nahl Volume 13 Number 3

Q3/2003 Vol. 13 No. 3 Al-Nahl A Quarterly Publication of Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. Baitul-Futuh: Islamic jewel in the heart of England. Exterior and Interior views. Special Issue of the Al-Nahl on the Life of Hadrat Dr. Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, radiyallahu ‘anhu. 60 pages, $2. Special Issue on Dr. Abdus Salam. 220 pages, 42 color and B&W pictures, $3. Ansar Ansar (Ansarullah News) is published monthly by Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. and is sent free of charge to all Ansar in the U.S. Ordering Information: Send a check or money order in the indicated amount along with your order to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905. Price includes shipping and handling within the continental U.S. Conditions of Bai‘at, Pocket-Size Edition Majlis Ansarullah, U.S.A. has published the ten conditions of initiation into the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in pocket size brochure. Contact your local officials for a free copy or write to Ansar Publications, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring MD 20905. Razzaq and Farida A story for children written by Dr. Yusef A. Lateef. Children and new Muslims, all can read and enjoy this story. It makes a great gift for the children of Ahmadi, Non-Ahmadi and Non- Muslim relatives, friends and acquaintances. The book contains colorful drawings. Please send $1.50 per copy to Chaudhary Mushtaq Ahmad, 15000 Good Hope Rd, Silver Spring, MD 20905 with your mailing address and phone number. Majlis Ansarullah U.S.A. will pay the postage and handling within the continental U.S. -

The Review of Religions, May 1988

THE REVIEW of RELIGIONS VOL LXXXIII NO. 5 MAY 1988 IN THIS ISSUE EDITORIAL GUIDE POSTS • SOURCES OF SIRAT • PRESS RELEASE • PERSECUTION IN PAKISTAN • ISLAM AND RUSSIA • BLISS OF KHILAFAT > EIGHTY YEARS AGO MASJID AL-AQSA THE AHMADIYYA MOVEMENT The Ahmadiyya Movement was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the expected world reformer and the Promissed Messiah whose advent had been foretold by the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be on him). The Movement is an embodiment of true and real Islam. It seeks to unite mankind with its Creator and to establish peace throughout the world. The present head of the Movement is Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. The Ahm-adiyya Movement has its headquarters at Rabwah, Pakistan, and is actively engaged in missionary work. EDITOR: BASHIR AHMAD ORCHARD ASSISTANT EDITOR: NAEEM OSMAN MEMON MANAGING EDITOR: AMATUL M. CHAUDHARY EDITORIAL BOARD B. A. RAFIQ (Chairman) A. M. RASHED M. A. SAQI The REVIEW of RELIGIONS A monthly magazine devoted to the dissemination of the teachings of Islam, the discussion of Islamic affairs and religion in general. \f The Review of Religions is an organ of the Ahmadiyya CONTENTS Page Movement which represents the pure and true Islam. It is open to all for discussing 1. Editorial 2 problems connected with the religious and spiritual 2. Guide Posts 3 growth of man, but it does (Bashir Ahmad Orchard) not accept responsibility for views expressed by 3. Sources of Sirat contributors. (Hazrat Mirza Bashir Ahmad) 4. Press Release 15 All correspondence should (Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry)' be forwarded directly to: 5. Persecution in Pakistan 16 The Editor, (Rashid Ahmad Chaudhry) The London Mosque, 16 Gressenhall Road, 6. -

Kassatly Chtaura

KASSATLY CHTAURA SPIRITS & BEVERAGE SECTOR Kassatly Chtaura Nahr el Mott, Beirut, Lebanon 2 Shrinkwrappers SMIFLEXI SK 350T GEO LOCATION INSTALLATION / Kassatly Chtaura 24 KASSATLY ften the combination of family tradition and strong CHTAURA O entrepreneurship is the basis for creating great opportunities for development in industry. If, then, the traditions handed down from generation to generation become real passions, success of the business is assured. An example of how true this is may be seen at the Lebanese company Kassatly Chtaura, which owes its success in the market to a clever fusion of family tradition, technological innovation and entrepreneurial know-how. The company’s historical roots date back raw materials and a systematic use of to 1974, when the current CEO Akram technological innovation. As for the Kassatly founded a small company latter, since 1997 the Lebanese company dedicated to the production of wine, has relied on the expertise of SMI that following the footsteps of his father since then has become a trusted partner Nicolas who worked in this field since of Kassatly Chtaura for the provision of 1919. Today, after almost forty years, a wide variety of high-tech packaging the name Kassatly Chtaura is linked to machines for the packaging of the BUZZ a wide and diverse range of drinks, in and FREEZ branded products. Recently, addition to wine, capable of satisfying the Lebanese company acquired two a growing number of consumers in all new Smiflexi SK 350T packers from SMI areas of the Middle East. designed to package in shrink film up The reason for this success is easily to 35 packs per minute with or without explained: behind Kassatly Chtaura tray. -

A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries

History in the Making Volume 1 Article 7 2008 A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries Adam D. Wilsey CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Wilsey, Adam D. (2008) "A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries," History in the Making: Vol. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol1/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 78 CSUSB Journal of History A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries Adam D. Wiltsey Linschoten, South and West Africa, Copper engraving (Amsterdam, 1596.) Accompanying the dawn of the twenty‐first century, there has emerged a new era of historical thinking that has created the need to reexamine the history of slavery and slave resistance. Slavery has become a controversial topic that historians and scholars throughout the world are reevaluating. In this modern period, which is finally beginning to honor the ideas and ideals of equality, slavery is the black mark of our past; and the task now lies History in the Making 79 before the world to derive a better understanding of slavery. In order to better understand slavery, it is crucial to have a more acute awareness of those that endured it. -

The Life of Imam Muhammad Al Jawad

Chapter 1 Dedication To the inspiring mind that has encouraged scientific and in- tellectual life on the earth, To the creative intellect that has initiated revival and cre- ation for Muslims, To the great Imam, Ja’far as-Sadiq, peace be upon him, I offer, with humbleness and reverence, this work, in which I have received the honor of researching the biography of his grandson Imam Muhammad al-Jawad, the miracle of intellect and knowledge in Islam, hoping it will be accepted… 2 Chapter 2 Introduction One of the most wonderful pictures of intellect and know- ledge in Islam is Imam Abu Ja’far Muhammad al-Jawad (a.s), who possessed the virtues and nobilities of the world, made springs of wisdom and knowledge flow in the earth and was the teacher and pioneer of the scientific and cultural revival of his age. Scholars, jurisprudents, narrators of traditions and learners of wisdom and sciences came to him to drink from the pure fount of his sciences and cultures. Jurisprudents have re- ported much from him concerning the verdicts of the Islamic Sharia, worships, mu’amalat[1] and other branches of jurispru- dence, and all have been recorded in the encyclopedias of jur- isprudence and Hadith. This great Imam was one of the founders of the jurispru- dence of the Ahlul Bayt[2] (a.s) that represented creation, ori- ginality and progress of intellect. [1] Ritual observances, social customs and ethical rules. [2] Ahlul Bayt is a term referring to the honored family of the Prophet (s), namely his daughter Fatima, Imam Ali, Imam Has- an, Imam Husayn and the other nine infallible imams descend- ing from Imam Husayn (peace be upon them all). -

Slavery in the Sudan: a Historical Survey 23

Durham E-Theses Domestic slavery in the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century northern Sudan Sharkey, Heather Jane How to cite: Sharkey, Heather Jane (1992) Domestic slavery in the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century northern Sudan, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5741/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Domestic Slavery in the Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Northern Sudan by Heather Jane Sharkey A thesis submitted to the University of Durham in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Modem Middle Eastern Studies. Centre for Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies University of Durham 1992 ? 1 Dec 1992 Table of Contents Abstract iii Acknowledgements iv A Note on Orthography and Transliteration v Chapter 1: The Subject and the Sources 1 Chapter -

Racial Justice Through Class Solidarity Within Communities of Color

The Community-Building Project: Racial Justice Through Class Solidarity Within Communities of Color Joseph Erasto Jaramillot INTRODUCTION As people of color continue to face racial and socioeconomic subordination in this country, one wonders when, if ever, the "elusive quest for racial justice"' will end. Intellectuals dedicated to the pursuit of racial justice have focused their work on unmasking the operation of racism and white privilege and recognizing the perspectives of the oppressed. One central insight of this approach is the need to take race into account when analyzing the application of supposedly "race neutral" but so often racially discriminatory criteria. This strategy provides a theoretical basis for transforming society's view of racism and race relations. However, until the dominant culture becomes genuinely receptive to these ideas, communities of color will continue to suffer.2 Indeed, current political discourse adds fuel Copyright 0 1996 by Joseph Jaramillo. t Joseph Erasto Jaramillo received his J.D. from the University of California, Berkeley School of Law (Boalt Hall), and his B.A. from the University of California at Davis. He is currently a staff attorney at the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) in San Francisco. He completed this Comment before he joined MALDEF. He would like to thank Professor Jerome McCristal Culp, Jr., of Duke University School of Law for his insight, former La Raza Law Journal Co- Editor-in-Chief Robert Salinas for his assistance and support, and Susana Martinez and Robby Mockler for their helpful editing and feedback. This Comment is dedicated to the committed gente of La Raza Law Students Association at Boalt Hall and all other schools, who give true meaning to the word "community." 1. -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

Contested Symbolism in the Flags of New World Slave Risings

Contested Symbolism in the Flags of New World Slave Risings Steven A. Knowlton Throughout the summer of 1800, an enslaved blacksmith of Richmond, Virginia, named Gabriel conspired with fellow bondspeople to rise in arms and fight for their freedom. Among his plans was a scheme to paint a flag with the phrase “Death or Liberty” to be carried at the head of the column that would march into the city.1 Gabriel’s slogan inverted the words of his fellow Virginian Patrick Henry, whose famous oration on the eve of the American Revolution concluded, “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”2 It is a well-known irony of history that among those who fought for American independence from British rule—and couched their rhetoric in terms of “freedom” and “liberty”—were some of the largest slaveholders on the continent, including Henry.3 In popular memory, their struggle against King George III has been valorized, but so have the efforts of those who sought emancipation for slaves. For example, historical markers now stand at key locations in Gabriel’s career, and the Richmond History Center has made an artist’s conception of Gabriel’s image one of fifty key objects that define the city’s story.4 (Figure 1) As Gabriel’s adaptation of Henry’s rhetoric demonstrates, opposing parties are known to assign conflicting meanings to shared symbols; flags are among the most prominent of these, as documented throughout vexillological literature.5 Slaves who engaged in violent conflict with their masters often used flags mod- eled on those of their oppressors.