UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sl.NO. B-345/1-2, KALATHIYA INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, DIAMOND

Bank of India LIST OF BENEFICIARIES DURING 2011-12 Sl.NO. Name of the Unit ADDRESS Amount ( In Rs.) 1 A. P. CAD CAM STREET NO. 3, TIRUPATI INDUSTRIAL AREA, 150 FEET 485,000.00 RING ROAD, RAJKOT 2 AADIKASH INDUSTRIES 39/40, KESHAV INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, NEAR NAGARVEL 397,200.00 HANUMAN TEMPLE, RAKHIAL, AHMEDABAD - 380023 3 AAKRUTI INDUSTRIAL BAPU NAGAR, JILLA GARDEN ROAD, RAJKOT - 360002 184,000.00 CORPORATION 4 AARCHI TEXTILES B-345/1-2, KALATHIYA INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, DIAMOND 227,000.00 NAGAR, LASKANA, KAMREJ, SURAT 5 ABHI GEMS VILLAGE UKHARLA, TALUKA GHOGHA, BHAVNAGAR 448,500.00 6 ACME MACHINERY NO. 1, VAIBHAV INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, NEAR TELECOM 1,135,000.00 FACTORY, SION - TROMBAY ROAD, DEONAR, BOMBAY - 400088 7 ADHYASHAKTI STEELS 226, SAGAR COMPLEX, JASONATH CHOWK, BHAVNAGAR 633,150.00 - 364001 8 ADHYASHAKTI TECHNOCAST 226, SAGAR COMPLEX, JASONATH CHOWK, BHAVNAGAR 268,800.00 - 364001 9 AIRTECH INDUSTRIES 56/1, NARASIMHAIAH GARDEN, KOTTIGEPALYA, MAGADI 200,000.00 MAIN ROAD, VISHWANEEDAM POST, BANGALORE - 560091 10 AISHWARYA RICE VILLAGE MATH, TALUKA TILDA, DIST. RAIPUR - 493421 206,550.00 INDUSTRIES 11 AJAY PLASTICS PLOT NO. B/81, BILESHWAR ESTATE, ODHAV RING ROAD 94,500.00 CIRCLE, AHMEDABAD - 382415 12 AKASH FABRICATION PATEL WADI, VILLAGE JESAR, TALUKA MAHUVA, BHAVNAGAR 285,000.00 13 AKSHAR CREATION PLOT NO. 6, MARGHIWALA COMPOUND, BAMROLI, SURAT 186,380.00 14 AKSHAR EMBROIDERY PLOT NO. 71, OLD GIDC, KATARGAM, SURAT 387,300.00 15 AMBICA ART P/302, NEW G.I.D.C., KATARGAM, SURAT 730,500.00 16 ANJALI DIAMOND PLOT NO. 34, MALDHARI SOCIETY, 1ST. FLOOR, BORTALAV 295,200.00 ROAD, DIST. -

A Regional Profile of Higher Education in Gujarat

ISSN No: 2455-734X (E-Journal) An Inter-Disciplinary National Peer & Double Reviewed e-Journal of Languages, Social Sciences and Commerce The Churning Uma Arts & Nathiba Commerce Mahila College, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India A Regional Profile of Higher Education in Gujarat Dr. Jaymal Rangiya Prof. Jyoti Panchal ABSTRACT Higher education is an important development indicator of social and economic growth of a nation. The present paper attempts to examine the disparities in number of higher educational institutions, main workers employed in institutions and gender distribution of main worker at district and regional levels. The statistical study involves social and geographical factors such as areas (districts), population, literacy level that are instrumental in creating regional imbalance with regard to the growth of highe r education in the state. The study is based on data extracted from statistical abstracts of Gujarat state for 2004 and 2009. For this study the four zones of Gujarat i.e. Central Gujarat, North Gujarat, South Gujarat and Saurastra – Kutch is taken into consideration. According to population census, 2001 the population of Gujarat state was 5.07 crore which is 5.96% of total population of India. According to population census 2001, Gujarat state is 7 Th largest state of India. The growth rate has increased from 21.19% of 1981-1991 periods to 22.66% in 1991-2001. This was found highest from 1951 to 1991 era. Total Population (in ‘000) 60,000 50,000 40,000 Total 30,000 Rural 20,000 Urban 10,000 0 1981 1991 2001 Literacy Rate of Gujarat March, 2016 Issue 1 www.uancmahilacollege.org Page 19 | 78 The Churning : An Inter-Disciplinary National Peer & Double Reviewed e-Journal of Languages, Social Sciences and Commerce/Dr. -

Marcia Hermansen, and Elif Medeni

CURRICULUM VITAE Marcia K. Hermansen October 2020 Theology Dept. Loyola University Crown Center 301 Tel. (773)-508-2345 (work) 1032 W. Sheridan Rd., Chicago Il 60660 E-mail [email protected] I. EDUCATION A. Institution Dates Degree Field University of Chicago 1974-1982 Ph.D. Near East Languages and Civilization (Arabic & Islamic Studies) University of Toronto 1973-1974 Special Student University of Waterloo 1970-1972 B.A. General Arts B. Dissertation Topic: The Theory of Religion of Shah Wali Allah of Delhi (1702-1762) C. Language Competency: Arabic, Persian, Urdu, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch, Turkish II. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY A. Teaching and Other Positions Held 2006- Director, Islamic World Studies Program, Loyola 1997- Professor, Theology Dept., Loyola University, Chicago 2003 Visiting Professor, Summer School, Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium 1982-1997 Professor, Religious Studies, San Diego State University 1985-1986 Visiting Professor, Institute of Islamic Studies McGill University, Montreal, Canada 1980-1981 Foreign Service, Canadian Department of External Affairs: Postings to the United Nations General Assembly, Canadian Delegation; Vice-Consul, Canadian Embassy, Caracas, Venezuela 1979-1980 Lecturer, Religion Department, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario M. K. Hermansen—2 B.Courses Taught Religious Studies World Religions: Major concepts from eastern and western religious traditions. Religions of India Myth and Symbol: Psychological, anthropological, and religious approaches Religion and Psychology Sacred Biography Dynamics of Religious Experience Comparative Spiritualities Scripture in Comparative Perspective Ways of Understanding Religion (Theory and Methodology in the Study of Religion) Comparative Mysticism Introduction to Religious Studies Myth, Magic, and Mysticism Islamic Studies Introduction to Islam. Islamic Mysticism: A seminar based on discussion of readings from Sufi texts. -

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

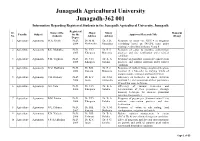

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

Year 2011-2012, 550 Scholars Had Visited the Library

ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 INTRODUCTION The Centre for Social Studies (CSS) is an autonomous social science research institute. Founded by late Professor I.P. Desai in 1969, as the Centre for Regional Development Studies, CSS receives grants for its recurring and non-recurring expenditure from the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi, and the Department of Higher and Technical Education, Government of Gujarat. Along with multi-disciplinary research, the Centre also provides guidance to Ph.D. students, organises training programmes and undertakes evaluations. With Gujarat as its core research area, the Centre also carries out studies related to other parts of the country for purposes of comparative analysis and to help develop a pan- Indian perspective. Research activities at the Centre are informed by a reflexive awareness of the social role of the researcher and the nature of social science research. Though the expression ‘social science research’ is of a relatively recent origin, the process of acquiring knowledge about society has a much longer and complex history. There have always been different approaches to the understanding of social reality and to the application of such knowledge to social transformation. For some, it has been an enterprise aimed at enabling the seeker of knowledge to transcend the social reality around him/her for personal salvation. Other analysts of social processes have claimed to be ‘value free’ even in their concern for an improved social order. In our view, researchers are always a part of the social reality and their concern must emanate from that reality. Their response cannot be only to try and change themselves in order to transcend the world within which they live. -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

Gadre 1943.Pdf

- Sri Pratapasimha Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantha-maia MEMOIR No. II. IMPORTANT INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE BARODA STATE. * Vol. I. Price Rs. 5-7-0 A. S. GADRE INTRODUCTION I have ranch pleasure in writing a short introduction to Memoir No, II in 'Sri Pratapsinh Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantharnala Series', Mr, Gadre has edited 12 of the most important epigraphs relating to this part of India some of which are now placed before the public for the first time. of its These throw much light on the history Western India and social and economic institutions, It is hoped that a volume containing the Persian inscriptions will be published shortly. ' ' Dilaram V. T, KRISHNAMACHARI, | Baroda, 5th July 1943. j Dewan. ii FOREWORD The importance of the parts of Gujarat and Kathiawad under the rule of His Highness the Gaekwad of Baroda has been recognised by antiquarians for a the of long time past. The antiquities of Dabhoi and architecture Northern the Archaeo- Gujarat have formed subjects of special monographs published by of India. The Government of Baroda did not however realise the logical Survey of until a necessity of establishing an Archaeological Department the State nearly decade ago. It is hoped that this Department, which has been conducting very useful work in all branches of archaeology, will continue to flourish under the the of enlightened rule of His Highness Maharaja Gaekwad Baroda. , There is limitless scope for the activities of the Archaeological Department in Baroda. The work of the first Gujarat Prehistoric Research Expedition in of the cold weather of 1941-42 has brought to light numerous remains stone age and man in the Vijapuf and Karhi tracts in the North and in Sankheda basin. -

South Zone Drawing Section -- Date: 10-10-2018

TO AHMEDABAD TO TO GODHARA NATIONAL HIGHWAY NO. 8 DUMAL TO AHMEDABAD TO GUJARAT FARTILIZER TO SAVLI NORTH DUMAD CHOWKDI CHHANI VEMALI SARDAR CHOK. NATIONALDENA HIGHWAY NO. 8 "A" TO GODHARA START POINT OF RUT-5 REFINERY TOWNSHIP RAMAKAKA GOLDAN CHOWKDI DEARI N A R M A D A C A N A L PRAMUKH SQ. RAJESHWAR HARMONY AMBIKA SOC. SUNDER VAN MOTNATH MAHADEV NAVRACHNA SOC. RAJESHWAR GOLD AKAS GANGA AKAS START POINT:-RUT-6 VEGETABLE & GRAIN MARKET N.T.S Trimurti KARODIYA AVANTISOC. HARANI 10 HANUMAN NARMADA KAILAS MAHADEV. TEMP. TALAV VASAHAT CHANAKYA SAMA UNDERA Abhilasha Sainik sport 24.0 M. JALARAM TEMPLE MOTIBHAI chhatralay complex E.M.E CIRCLE HIGH WAY BY PASS 100.0 M. METRO ROAD 24.0M. Transportnagar 24.0 M. 18.0 M. NAVARACHNA NANUBHAI TOWER SCHOOL 30.0 M. 12 MAHESANA Panchavati DARJIPURA ROAD 24.0 M. CIRCLE Mehsana nagar MANGAL PANDEY RD. D-CABIN SAYAJIPURA AIRPORT TOWN HALL TO AJWA Delux KANHA RESI 18.0 M. 7 MUKHI NGR.TRAN RASTA MANEKPARK AJWA O.H.TANK CROSS RD. Amitnagar Soc. KALPANA NEW V.I.P. ROAD CANTONMENT V.I.P. ROAD SOCIETY 40.0 M. GORWA 40.0 M. S.R.Petrol Pump LAXMI STUDIO NIZAMPURA HANUMAN START POINT:-RUT-1 Ghelani Petrol Pump TEMP. LAXMIPURA KHODIYARNAGAR 18.0 M. "T" "C" VUDA END POINT:-RUT-6 WARD NO:2 20.0M. BHAVAN 36.0 M. 20.0 M. 30.0 M. 14 HARANI ROAD WARD:7 OFFICE 9 Nagar Anand END POINT OF RUT-5 SANGAM END POINT:-RUT-1 C.K PRAJAPATI SCHOOL Fateganj Circle 36.0 CROSS RD. -

6, Admihistaation the Following Pages Aspire to Present the Picture

6 , ADMIHISTaATION The following pages aspire to present the picture of government machinery and its working in this region during the period under study. The task Is rendered easier, and the onus Is lightened by the eminent authorities on the subject who have, so far, iwltten on the administration of the various dynasties with which the present study Is con cerned. naturally It Is deemed proper to refrain from deal ing In details of the administrative machinery functioning fro® the Vakitaka period to that of the Yadavas. In the following pages, therefore, the administrative asoects, the Information about which we could deduce from the eplgraohs found In this region, are only dealt with. Our principal sources of information, in this connection, are therefore, m the statements made In the epigraphs. The information gleaned from the epigraphs found outside our academic Jurisdiction has also been made use of tw>, present a fuller and better persoective. All the data have been occasionally compared to the rules laid dovmr by the contemoorary Smrtl• writers and statements in the records of other contemporary dynasties. Accounts of the Muslim traders have also been 55 Utilized, If the picture of the administrative machinery presented below is not comoletej it does not mean that the machinery was defective or imperfect. It would simply mean that our scope is limited and we could not get adequate information to make it a complete one. Moreover it should be noted that the dynasties under study were ruling over extensive empires and this region was one of the parts of those. -

Alauddin Khalji's Conquest of Malwa

Alauddin Khalji's conquest of Malwa Alauddin Khilji: the greatest ruler of the Khilji Dynasy in India! Alauddin Khilji (d.o.b. unknown-1316) was the greatest ruler of the Khilji Dynasy in India. During his reign, he successfully invaded 6 territories, conquering all of these territories in Northern India. Khilji also conquered territories in Southern India as well. After all of the conquests of India, he took control of all of the nobility. Khilji died of edema. Alauddin Khilji was born in Delhi in 1266 CE, lived his entire life in the Indian subcontinent, and ruled as sultan of Delhi from 1296 CE â“ 1316 CE. By any definition, he would have to be called an Indian monarch, not a foreign invader. As a ruler, he would prove himself to be one of Indiaâ™s greatest warrior kings and one of the worldâ™s great military geniuses. Khilji greatly expanded the empire that he inherited from his uncle, Sultan Jalaluddin Khilji, after killing him. Many of his conquests were of kingdoms ruled by Hindu kings, including Chittor, Devgiri, Warangal (from where he acquired the famous Kohinoor diamond), Gujarat, Ranthambore, and the Hoysala and Pandya kingdoms. In 1299, the Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji sent an army to ransack the Gujarat region of India, which was ruled by the Vaghela king Karna. The Delhi forces plundered several major cities of Gujarat, including Anahilavada (Patan), Khambhat, Surat and Somnath. Karna was able to regain control of at least a part of his kingdom in the later years. However, in 1304, a second invasion by Alauddin's forces permanently ended the Vaghela dynasty, and resulted in the annexation of Gujarat to the Delhi In 1305, the Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji sent an army to capture the Paramara kingdom of Malwa in central India. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Marcia K. Hermansen September 2020

CURRICULUM VITAE Marcia K. Hermansen September 2020 Theology Dept. Loyola University Crown Center 301 Tel. (773)-508-2345 (work) 1032 W. Sheridan Rd., Chicago Il 60660 E-mail [email protected] I. EDUCATION A. Institution Dates Degree Field University of Chicago 1974-1982 Ph.D. Near East Languages and Civilization (Arabic & Islamic Studies) University of Toronto 1973-1974 Special Student University of Waterloo 1970-1972 B.A. General Arts B. Dissertation Topic: The Theory of Religion of Shah Wali Allah of Delhi (1702-1762) C. Language Competency: Arabic, Persian, Urdu, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch, Turkish II. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY A. Teaching and Other Positions Held 2006- Director, Islamic World Studies Program, Loyola 1997- Professor, Theology Dept., Loyola University, Chicago 2003 Visiting Professor, Summer School, Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium 1982-1997 Professor, Religious Studies, San Diego State University 1985-1986 Visiting Professor, Institute of Islamic Studies McGill University, Montreal, Canada 1980-1981 Foreign Service, Canadian Department of External Affairs: Postings to the United Nations General Assembly, Canadian Delegation; Vice-Consul, Canadian Embassy, Caracas, Venezuela 1979-1980 Lecturer, Religion Department, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario M. K. Hermansen—2 B.Courses Taught Religious Studies World Religions: Major concepts from eastern and western religious traditions. Religions of India Myth and Symbol: Psychological, anthropological, and religious approaches Religion and Psychology Sacred Biography Dynamics of Religious Experience Comparative Spiritualities Scripture in Comparative Perspective Ways of Understanding Religion (Theory and Methodology in the Study of Religion) Comparative Mysticism Introduction to Religious Studies Myth, Magic, and Mysticism Islamic Studies Introduction to Islam. Islamic Mysticism: A seminar based on discussion of readings from Sufi texts.