Revisiting the Golden Age and Its Heroes a Historical Comparative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BATAVIA, RE-VISITED Brian Lemin. for Those of You Who Have

THE BATAVIA, RE-VISITED Brian Lemin. For those of you who have not "visited" the Batavia for the first time as yet, you should plan to read Rosemary Shepherd’s article in OIDFA 1994/1, where she not only retells the story of the Batavia, but more importantly reconstructs the lace found on this important vessel. INTRODUCTION A wonderful reconstruction of the vessel Batavia, which was wrecked off the West coast of Australia in 1629, is visiting Sydney for the Olympic year 2000, and being brought up as a seafaring man and lately a bobbin man, I wanted to see it. She belonged to the Dutch East India Company and was designed as a "return" ship. That is it was made to bring back spices, tea and other valuable products from the East Indies. The original was wrecked in 1929 some 60 kms. off the west coast of Australia, and since its discovery in 1963 it has been subject to maritime archaeological investigation and retrieval. Amongst the finds were some fragments of lace The Batavia in Darling Harbour. Sydney. and two lace bobbins. Hence and article on it in this web page. THE STORY. This story has all the ingredients for what my generation called a "Boys Own Paper" adventure. Indeed Rosemary’s article starts with the sentence, "Desertion, Mutiny and murder awaited the crew on the unfortunate ship". Frankly I think she understated the brutality of the events and even the eventual brutality of the punishments for the perpetrators of such crimes. But I go ahead of myself. It is not the purpose to of this article to retell the story of the Batavia, but rather to uses it as a stepping stone to looking at the bobbins that they found on the wreck, but having whetted your appetite I must at least précis the events for you. -

Gouverneur-Generaals Van Nederlands-Indië in Beeld

JIM VAN DER MEER MOHR Gouverneur-generaals van Nederlands-Indië in beeld In dit artikel worden de penningen beschreven die de afgelo- pen eeuwen zijn geproduceerd over de gouverneur-generaals van Nederlands-Indië. Maar liefs acht penningen zijn er geslagen over Bij het samenstellen van het overzicht heb ik de nu zo verguisde gouverneur-generaal (GG) voor de volledigheid een lijst gemaakt van alle Jan Pieterszoon Coen. In zijn tijd kreeg hij geen GG’s en daarin aangegeven met wie er penningen erepenning of eremedaille, maar wel zes in de in relatie gebracht kunnen worden. Het zijn vorige eeuw en al in 1893 werd er een penning uiteindelijk 24 van de 67 GG’s (niet meegeteld zijn uitgegeven ter gelegenheid van de onthulling van de luitenant-generaals uit de Engelse tijd), die in het standbeeld in Hoorn. In hetzelfde jaar prijkte hun tijd of ervoor of erna met één of meerdere zijn beeltenis op de keerzijde van een prijspen- penningen zijn geëerd. Bij de samenstelling van ning die is geslagen voor schietwedstrijden in dit overzicht heb ik ervoor gekozen ook pennin- Den Haag. Hoe kan het beeld dat wij van iemand gen op te nemen waarin GG’s worden genoemd, hebben kantelen. Maar tegelijkertijd is het goed zoals overlijdenspenningen van echtgenotes en erbij stil te staan dat er in andere tijden anders penningen die ter gelegenheid van een andere naar personen en functionarissen werd gekeken. functie of gelegenheid dan het GG-schap zijn Ik wil hier geen oordeel uitspreken over het al dan geslagen, zoals die over Dirck Fock. In dit artikel niet juiste perspectief dat iedere tijd op een voor- zal ik aan de hand van het overzicht stilstaan bij val of iemand kan hebben. -

Western Australian Museum - Maritime

WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM - MARITIME Ephemera PR9931/MAR To view items in Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia. CALL NO. DESCRIPTION R9931/MAR/1 S.S. Xantho: Western Australia's first coastal steamer. Information pamphlet. c1986 D PR9931/MAR/2 Sailing ships. Information pamphlet. 1986. D PR9931/MAR/3 Your Museum. The Western Australian Maritime Museum. Pamphlet. c1981 PR9931/MAR/4 Shipwrecks and the Maritime Museum. Public Lecture. November 1986 PR9931/MAR/5 Western Australian Maritime Museum. Pamphlet. c1987 PR9931/MAR/6 The Batavia Timbers Project. Brochure. c1987 PR9931/MAR/7 The Batavia Timbers Project. Brochure. c1987 PR9931/MAR/8 Western Australian Maritime Museum. Pamphlet. c1982 PR9931/MAR/9 Wrecks in the Houtman Abrolhos Islands. Pamphlet. 1993 PR9931/MAR/10 Wrecks of the Coral Coast. Pamphlet. 1993 PR9931/MAR/11 A Different Art-Trade Union Banners September 5-October 4, 1981. Pamphlet. D PR9931/MAR/12 The Trustees of the Western Australian Museum would be delighted if…could attend a “Twilight Preview” to celebrate the completion of construction and official hand over of the spectacular… Card. 2002. PR9931/MAR/13 Telling Stories. 1p. Undated. PR9931/MAR/14 Western Australian Maritime Museum. Fold-out leaflet. 2003. PR9931/MAR/15 Living on the edge : the coastal experience. Fold-out leaflet. 2003. PR9931/MAR/16 Let’s piece together our history. Celebrate your heritage with Welcome Walls! A4 Poster. Undated. PR9931/MAR/17 Commemorate your family’s migrant heritage. The WA Maritime Museum Welcome Walls. Stage 3. Fold-out leaflet. Undated. PR9931/MAR/18 Voyages of grand discovery. Lecture series 2007. -

Australia's First Criminal Prosecutions in 1629

Australia’s First Criminal Prosecutions in 1629 Rupert Gerritsen Batavia Online Publishing Australia’s First Criminal Prosecutions in 1629 Batavia Online Publishing Canberra, Australia http://rupertgerritsen.tripod.com Published by Batavia Online Publishing 2011 Copyright © Rupert Gerritsen National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Author: Gerritsen, Rupert, 1953- Title: Australia’s First Criminal Prosecutions in 1629 ISBN: 978-0-9872141-2-6 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographic references Subjects: Batavia (Ship) Prosecution--Western Australia--Houtman Abrolhos Island.s Mutiny--Western Australia--Houtman Abrolhos Islands--History. Houtman Abrolhos Islands (W.A.) --History. Dewey Number: 345.941025 CONTENTS Introduction 1 The Batavia Mutiny 1 The Judicial Context 5 Judicial Proceedings Following 7 The Mutiny The Trials 9 The Executions 11 Other Legal Proceedings and Issues - 12 Their Outcomes and Implications Bibliography 16 Notes 19 Australia’s First Criminal Prosecutions in 1629 Rupert Gerritsen Introduction The first criminal proceedings in Australian history are usually identified as being the prosecution of Samuel Barsley, or Barsby, Thomas Hill and William Cole in the newly-established colony of New South Wales on 11 February 1788. Barsley was accused of abusing Benjamin Cook, Drum-Major in the marines, and striking John West, a drummer in the marines. It was alleged Hill had stolen bread valued at twopence, while Cole was charged with stealing two deal planks valued at ten pence. The men appeared before the Court of Criminal Judicature, the bench being made up of Judge-Advocate Collins and a number of naval and military officers - Captains Hunter, Meredith and Shea, and Lieutenants Ball, Bradley and Creswell.1,2 However, the first criminal prosecutions to take place on what is now Australian soil actually occurred in more dramatic circumstances in 1629. -

Islam in Christian Tolerance

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘Let the Muslim be my Master in Outward Things’. References to Islam in the Promotion of Religious Tolerance in Christian Europe AUTHORS Abdul Haq Compier JOURNAL Al-Islam eGazette DEPOSITED IN ORE 01 February 2010 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/90953 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Abdul Haq Compier ‘Let the Muslim be my Master in Outward Things’ Al-Islam eGazette, January 2010 ‘Let the Muslim be my Master in Outward Things’. References to Islam in the Promotion of Religious Tolerance in Christian Europe ABDUL HAQ COMPIER 1 SUMMARY................................................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 TOLERANCE IN ISLAM ................................................................................................................................................ 4 CHRISTIAN REFERENCES TO MUSLIM POLICY .......................................................................................................... 6 From Jerusalem to Constantinople .................................................................................................................... -

Jan Pieterszoon Coen Op School Historisch Besef En Geschiedenisonderwijs in Nederland, 1857 – 2011

Jan Pieterszoon Coen op school Historisch besef en geschiedenisonderwijs in Nederland, 1857 – 2011 Jasper Rijpma 0618047 Blasiusstraat 55D 1091CL Amsterdam 0618047 [email protected] Masterscriptie geschiedenis Universiteit van Amsterdam Scriptiebegeleider: dr. C.M. Lesger Januari 2012 De prent in de linker bovenzijde is afkomstig uit het tweede deeltje van de katholieke geschiedenismethode voor het lager onderwijs Rood, wit en blauw uit 1956. Het onderschrift luidt: „In 1619 werd Jacatra verbrand. Op de puinhopen stichtte Jan Pietersz. Coen Batavia. Een inlander houdt een pajong boven het hoofd van Coen. Een landmeter laat Coen een kaart zien, waarop hij het plan van de nieuwe stad heeft getekend.‟ (Met dank aan Lucia Hogervorst) De prent in de rechter onderzijde is afkomstig uit de historische stripserie Van nul tot nu uit 1985. De tekst in het ingevoegde gele kader luidt: „Een van de bekendste gouverneurs-generaal was Jan Pieterszoon Coen. Hij verdreef de Engelsen van het eiland Java en stichtte er de stad Batavia. Batavia heet nu Djakarta en is de hoofdstad van Indonesië. Batavia werd al gauw het middelpunt van alle Nederlandse koloniën in het Oosten‟. De tekst in het grootste kader luidt: „De bezetting van Oost-Indie lukte beter. Men benoemde een gouverneur-generaal in Indië die de opdracht had de boel daar goed te besturen en alle zaken “eerlijk” te regelen… Dat daar wel enige dwang aan te pas kwam, vond iedereen toen normaal: blanken stonden immers boven gekleurde mensen?‟ Op het plaatje is Jan Pieterszoon Coen te herkennen. Hij zegt tegen een aantal Indiërs: “Wij hebben specerijen nodig en geen rijst! Neemt allen dus een schop en spit uw dessa om!. -

Oriel College Record

Oriel College Record 2020 Oriel College Record 2020 A portrait of Saint John Henry Newman by Walter William Ouless Contents COLLEGE RECORD FEATURES The Provost, Fellows, Lecturers 6 Commemoration of Benefactors, Provost’s Notes 13 Sermon preached by the Treasurer 86 Treasurer’s Notes 19 The Canonisation of Chaplain’s Notes 22 John Henry Newman 90 Chapel Services 24 ‘Observing Narrowly’ – Preachers at Evensong 25 The Eighteenth Century World Development Director’s Notes 27 of Revd Gilbert White 92 Junior Common Room 28 How Does a Historian Start Middle Common Room 30 a New Book? She Goes Cycling! 95 New Members 2019-2020 32 Eugene Lee-Hamilton Prize 2020 100 Academic Record 2019-2020 40 Degrees and Examination Results 40 BOOK REVIEWS Awards and Prizes 48 Gonzalo Rodriguez-Pereyra, Leibniz: Graduate Scholars 48 Discourse on Metaphysics 104 Sports and Other Achievements 49 Robert Wainwright, Early Reformation College Library 51 Covenant Theology: English Outreach 53 Reception of Swiss Reformed Oriel Alumni Advisory Committee 55 Thought, 1520-1555 106 CLUBS, SOCIETIES NEWS AND ACTIVITIES Honours and Awards 110 Chapel Music 60 Fellows’ and Lecturers’ News 111 College Sports 63 Orielenses’ News 114 Tortoise Club 78 Obituaries 116 Oriel Women’s Network 80 Other Deaths notified since Oriel Alumni Golf 82 August 2019 135 DONORS TO ORIEL Provost’s Court 138 Raleigh Society 138 1326 Society 141 Tortoise Club Donors 143 Donors to Oriel During the Year 145 Diary 154 Notes 156 College Record 6 Oriel College Record 2020 VISITOR Her Majesty the Queen -

Houtman Abrolhos Islands National Park Draft Management Plan 2021

Houtman Abrolhos Islands National Park draft management plan 2021 Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Conservation and Parks Commission Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions 17 Dick Perry Avenue KENSINGTON WA 6151 Phone: (08) 9219 9000 Fax: (08) 9334 0498 dbca.wa.gov.au © State of Western Australia 2021 2021 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). ISBN 978-1-925978-16-2 (online) ISBN 978-1-925978-15-5 (print) This management plan was prepared by the Conservation and Parks Commission through the agency of the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. Questions regarding this management plan should be directed to: Aboriginal Engagement, Planning and Lands Branch Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 Phone: (08) 9219 9000 The recommended reference for this publication is: Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (2021) Houtman Abrolhos Islands National Park draft management plan, 2021. Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Perth. This document is available in alternative formats on request. Front -

Company Privateers in Asian Waters: the VOC-Trading Post at Hirado Knoest, Jurre

Company Privateers in Asian Waters: The VOC-Trading Post at Hirado Knoest, Jurre Citation Knoest, J. (2011). Company Privateers in Asian Waters: The VOC-Trading Post at Hirado. Leidschrift : Een Behouden Vaart?, 26(December), 43-57. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/72846 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/72846 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Artikel/Article: Company Privateers in Asian Waters: The VOC-Trading Post at Hirado and the Logistics of Privateering, ca. 1614-1624 Auteur/Author: Jurre Knoest Verschenen in/Appeared in: Leidschrift, 26.3 (Leiden 2011) 43-57 Titel uitgave: Een behouden vaart? De Nederlandse betrokkenheid bij kaapvaart en piraterij © 2011 Stichting Leidschrift, Leiden, The Netherlands ISSN 0923-9146 E-ISSN 2210-5298 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden No part of this publication may be gereproduceerd en/of vermenigvuldigd reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de transmitted, in any form or by any means, uitgever. electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Leidschrift is een zelfstandig wetenschappelijk Leidschrift is an independent academic journal historisch tijdschrift, verbonden aan het dealing with current historical debates and is Instituut voor geschiedenis van de Universiteit linked to the Institute for History of Leiden Leiden. Leidschrift verschijnt drie maal per jaar University. Leidschrift appears tri-annually and in de vorm van een themanummer en biedt each edition deals with a specific theme. hiermee al vijfentwintig jaar een podium voor Articles older than two years can be levendige historiografische discussie. -

Batavia" Was Wrecked on a Reef of the Houtman Abrolhos Over a Drunken Brawl at the Cape of Good Hope

(RlfflE & PUNISHTTIEMT dusnuudnby oMGinsi P. LID DY MAGISTRATE, ADELAIDE In 1629 the Dutch East India Company's merchant ship During the journey, the Skipper was reprimanded by Pelsaert "Batavia" was wrecked on a reef of the Houtman Abrolhos over a drunken brawl at the Cape of Good Hope. Jacobsz off the Western Australian Coast, about 300 miles north of began to plot mutiny and when advances made by him to Perth. The events which followed make "M utiny on the wards Lucretia Jansz were rebuffed he devised a scheme which Bounty" read like the "Teddy Bears Picnic" — drownings would kill two birds with the one stone. The idea was to seize sunken treasure chests, rape and murder. Lucretia one night, strip her and smear her with excreta and Interesting, but what causes a lawyer to write about it in a pitch and thereby provoke Pelsaert to take punitive measures journal such as this? Well, although accounts of the incident which would cause the crew (many of whom were unfavour have been published from time to time, one aspect of the ably disposed towards Lucretia, but sympathetic with the Batavia wrecking which has not received the attention it Skipper) to join forces with Jacobsz, overthrow the Comm- deserves — certainly not by legal or penal historians (to my andeur and take the ship. After killing any of the crew who knowledge there has never been so much as a mention of the remained loyal to Pelsaert, they would use the ship and chests matter in any account of Australian criminal history) — is of money as the starting point for a life of piracy along the that it produced the first crime in our country's history, our Barbary and African Coasts. -

Masterscriptie Tycho Hofstra Master Cultuurgeschiedenis Faculteit Der

Masterscriptie Tycho Hofstra Master Cultuurgeschiedenis Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen, Universiteit van Amsterdam Begeleider: dr. J.C. van Zanten Tweede lezer: dr. J.J.B. Turpijn Amsterdam, juni 2016 Afbeelding omgslag v.l.n.r: R. Fruin, J. Huizinga, A.A. van Schelven, E.H. Kossmann Tweede rij v.l.n.r: G.W. Kernkamp, J.M. Romein, C.H.Th. Bussemaker, J.C. Boogman Derde rij v.l.n.r: G.J. Presser, P.J Blok, P.C.A. Geyl, A. Goslinga Inhoudsopgave Inleiding ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1. De grondslag van Fruin (1860-1894) .................................................................................. 7 1.1 Fruin .................................................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Blok ................................................................................................................................ 11 2. De crisis van de hulpwetenschappen (1865-1890) ........................................................... 16 2.1 Jorissen ........................................................................................................................... 16 2.2 Wijnne ............................................................................................................................ 17 2.3 Rogge .............................................................................................................................. 19 3. Stabilisatie in staatsgeschiedenis -

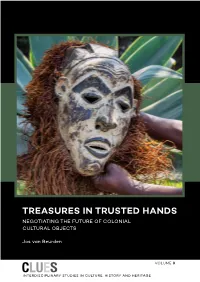

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art.