Labour's Lost Legions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand's Efforts to Eliminate Violence Against Women

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Crowley Mission Reports Leitner Center for International Law and Justice 2008 "It's Not OK": New Zealand's Efforts to Eliminate Violence Against Women Jeanmarie Fenrich Exectutive Director, Leitner Center for International Law and Justice, [email protected] Jorge Contesse Crowley Fellow 2007-2008 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/crowley_reports Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Fenrich, Jeanmarie and Contesse, Jorge, ""It's Not OK": New Zealand's Efforts to Eliminate Violence Against Women" (2008). Crowley Mission Reports. 1. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/crowley_reports/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Leitner Center for International Law and Justice at FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Crowley Mission Reports by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leitner Center for International Law and Justice “It’s not OK”: Fordham Law School New Zealand’s Efforts to Eliminate Violence Against Women 33 West 60th Street Second Floor New York, NY 10023 NEW ZEALAND REPPORT 212.636.6862 www.leitnercenter.org “IT’S NOT OK” “IT’S NOT OK”: New Zealand’s Efforts to Eliminate Violence Against Women Jeanmarie Fenrich Jorge Contesse Executive Director, Crowley Fellow 2007-08 Leitner Center for International Leitner Center for International Law and Justice Law and Justice Fordham Law School Fordham Law School Cover: Mural image usage by courtesy of Bream Bay Community Support Trust, Ruakaka, Northland. -

South & East Auckland

G A p R D D Paremoremo O N R Sunnynook Course EM Y P R 18 U ParemoremoA O H N R D E M Schnapper Rock W S Y W R D O L R SUNSET RD E R L ABERDEEN T I A Castor Bay H H TARGE SUNNYNOOK S Unsworth T T T S Forrest C Heights E O South & East Auckland R G Hill R L Totara Vale R D E A D R 1 R N AIRA O S Matapihi Point F W F U I T Motutapu E U R RD Stony Batter D L Milford Waitemata THE R B O D Island Thompsons Point Historic HI D EN AR KITCHENER RD Waihihi Harbour RE H Hakaimango Point Reserve G Greenhithe R R TRISTRAM Bayview D Kauri Point TAUHINU E Wairau P Korakorahi Point P DIANA DR Valley U IPATIKI CHIVALRY RD HILLSIDERD 1 A R CHARTWELL NZAF Herald K D Lake Takapuna SUNNYBRAE RD SHAKESPEARE RD ase RNZAF T Pupuke t Island 18 Glenfield AVE Takapuna A Auckland nle H Takapuna OCEAN VIEW RD kland a I Golf Course A hi R Beach Golf Course ro O ia PT T a E O Holiday Palm Beach L R HURSTMERE RD W IL D Park D V BEACH HAVEN RD NORTHCOTE R BAY RD R N Beach ARCHERS RD Rangitoto B S P I O B E K A S D A O D Island Haven I R R B R A I R K O L N U R CORONATION RD O E Blackpool H E Hillcrest R D A A K R T N Church Bay Y O B A SM K N D E N R S Birkdale I R G Surfdale MAN O’WA Hobsonville G A D R North Shore A D L K A D E Rangitawhiri Point D E Holiday Park LAK T R R N OCEANRALEIGH VIEW RD I R H E A R E PUPUKE Northcote Hauraki A 18 Y D EXMOUTH RD 2 E Scott Pt D RD L R JUTLAND RD E D A E ORAPIU RD RD S Birkenhead V I W K D E A Belmont W A R R K ONEWA L HaurakiMotorway . -

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola. "South - the Endurance of the Old, the Shock of the New." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 60-75. Roger, W. "Six Months in Another Town." Auckland Metro 40 (1984): 155-70. ———. "West - in Struggle Country, Battlers Still Triumph." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 88-99. Young, C. "Newmarket." Auckland Metro 38 (1984): 118-27. 1 General works (21) "Auckland in the 80s." Metro 100 (1989): 106-211. "City of the Commonwealth: Auckland." New Commonwealth 46 (1968): 117-19. "In Suburbia: Objectively Speaking - and Subjectively - the Best Suburbs in Auckland - the Verdict." Metro 81 (1988): 60-75. "Joshua Thorp's Impressions of the Town of Auckland in 1857." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 35 (1979): 1-8. "Photogeography: The Growth of a City: Auckland 1840-1950." New Zealand Geographer 6, no. 2 (1950): 190-97. "What’s Really Going On." Metro 79 (1988): 61-95. Armstrong, Richard Warwick. "Auckland in 1896: An Urban Geography." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1958. Elphick, J. "Culture in a Colonial Setting: Auckland in the Early 1870s." New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1974): 1-14. Elphick, Judith Mary. "Auckland, 1870-74: A Social Portrait." M.A. thesis (History), University of Auckland, 1974. Fowlds, George M. "Historical Oddments." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 4 (1964): 35. Halstead, E.H. "Greater Auckland." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1934. Le Roy, A.E. "A Little Boy's Memory of Auckland, 1895 to Early 1900." Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal 51 (1987): 1-6. Morton, Harry. -

Route N10 - City to Otara Via Manukau Rd, Onehunga, Mangere and Papatoetoe

ROUTE N10 - CITY TO OTARA VIA MANUKAU RD, ONEHUNGA, MANGERE AND PAPATOETOE Britomart t S Mission F t an t r t sh e S e S Bay St Marys aw Qua College lb n A y S e t A n Vector Okahu Bay St Heliers Vi e z ct t a o u T r S c Arena a Kelly ia Kohimarama Bay s m A S Q Tarltons W t e ak T v a e c i m ll e a Dr Beach es n ki le i D y S Albert r r t P M Park R Mission Bay i d a Auckland t Dr St Heliers d y D S aki r Tama ki o University y m e e Ta l r l l R a n Parnell l r a d D AUT t S t t S S s Myers n d P Ngap e n a ip Park e r i o Auckland Kohimarama n R u m e y d Domain d Q l hape R S R l ga d an R Kar n to d f a N10 r Auckland Hobson Bay G Hospital Orakei P Rid a d de rk Auckland ll R R R d d Museum l d l Kepa Rd R Glendowie e Orakei y College Grafton rn Selwyn a K a B 16 hyb P College rs Glendowie Eden er ie Pass d l Rd Grafton e R d e Terrace r R H Sho t i S d Baradene e R k h K College a Meadowbank rt hyb r No er P Newmarket O Orakei ew ass R Sacred N d We Heart Mt Eden Basin s t Newmarket T College y a Auckland a m w a ki Rd Grammar d a d Mercy o Meadowbank R r s Hospital B St Johns n Theological h o St John College J s R t R d S em Remuera Va u Glen ll d e ey G ra R R d r R Innes e d d St Johns u a Tamaki R a t 1 i College k S o e e u V u k a v lle n th A a ra y R R d s O ra M d e Rd e u Glen Innes i em l R l i Remuera G Pt England Mt Eden UOA Mt St John L College of a Auckland Education d t University s i e d Ak Normal Int Ea Tamaki s R Kohia School e Epsom M Campus S an n L o e i u n l t e e d h re Ascot Ba E e s Way l St Cuthberts -

Before a Board of Inquiry East West Link Proposal

BEFORE A BOARD OF INQUIRY EAST WEST LINK PROPOSAL Under the Resource Management Act 1991 In the matter of a Board of Inquiry appointed under s149J of the Resource Management Act 1991 to consider notices of requirement and applications for resource consent made by the New Zealand Transport Agency in relation to the East West Link roading proposal in Auckland Statement of Evidence in Chief of Anthony David Cross on behalf of Auckland Transport dated 10 May 2017 BARRISTERS AND SOLICITORS A J L BEATSON SOLICITOR FOR THE SUBMITTER AUCKLAND LEVEL 22, VERO CENTRE, 48 SHORTLAND STREET PO BOX 4199, AUCKLAND 1140, DX CP20509, NEW ZEALAND TEL 64 9 916 8800 FAX 64 9 916 8801 EMAIL [email protected] Introduction 1. My full name is Anthony David Cross. I currently hold the position of Network Development Manager in the AT Metro (public transport) division of Auckland Transport (AT). 2. I hold a Bachelor of Regional Planning degree from Massey University. 3. I have 31 years’ experience in public transport planning. I worked at Wellington Regional Council between 1986 and 2006, and the Auckland Regional Transport Authority between 2006 and 2010. I have held my current role since AT was established in 2010. 4. In this role, I am responsible for specifying the routes and service levels (timetables) for all of Auckland’s bus services. Since 2012, I have led the AT project known as the New Network, which by the end of 2018 will result in a completely restructured network of simple, connected and more frequent bus routes across all of Auckland. -

Life Stories of Robert Semple

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. From Coal Pit to Leather Pit: Life Stories of Robert Semple A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of a PhD in History at Massey University Carina Hickey 2010 ii Abstract In the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Len Richardson described Robert Semple as one of the most colourful leaders of the New Zealand labour movement in the first half of the twentieth century. Semple was a national figure in his time and, although historians had outlined some aspects of his public career, there has been no full-length biography written on him. In New Zealand history his characterisation is dominated by two public personas. Firstly, he is remembered as the radical organiser for the New Zealand Federation of Labour (colloquially known as the Red Feds), during 1910-1913. Semple’s second image is as the flamboyant Minister of Public Works in the first New Zealand Labour government from 1935-49. This thesis is not organised in a chronological structure as may be expected of a biography but is centred on a series of themes which have appeared most prominently and which reflect the patterns most prevalent in Semple’s life. The themes were based on activities which were of perceived value to Semple. Thus, the thematic selection was a complex interaction between an author’s role shaping and forming Semple’s life and perceived real patterns visible in the sources. -

South & East Auckland Auckland Airport

G A p R D D Paremoremo O N R Sunnynook Course EM Y P R 18 U ParemoremoA O H N R D E M Schnapper Rock W S Y W R D O L R SUNSET RD E R L ABERDEEN T I A Castor Bay H H TARGE SUNNYNOOK S Unsworth T T T S Forrest C Heights E O South & East Auckland R G Hill R L Totara Vale R D E A D R 1 R N AIRA O S Matapihi Point F W F U I T Motutapu E U R RD Stony Batter D L Milford Waitemata THE R B O D Island Thompsons Point Historic HI D EN AR KITCHENER RD Waihihi Harbour RE H Hakaimango Point Reserve G Greenhithe R R TRISTRAM Bayview D Kauri Point TAUHINU E Wairau P Korakorahi Point P DIANA DR Valley U IPATIKI CHIVALRY RD HILLSIDERD 1 A R CHARTWELL NZAF Herald K D Lake Takapuna SUNNYBRAE RD SHAKESPEARE RD ase RNZAF T Pupuke t Island 18 Glenfield AVE Takapuna A Auckland nle H Takapuna OCEAN VIEW RD kland a I Golf Course A hi R Beach Golf Course ro O ia PT T a E O Holiday Palm Beach L R HURSTMERE RD W IL D Park D V BEACH HAVEN RD NORTHCOTE R N Beach ARCHERS RD Rangitoto B S P I O B E K A S D A O Island Haven I RD R B R A I R K O L N U R CORONATION RD O E Blackpool H E Hillcrest R D A A K R T N Church Bay Y O B A SM K N D E N R S Birkdale I R G Surfdale MAN O’WAR BAY RD Hobsonville G A D R North Shore A D L K A D E Rangitawhiri Point D E Holiday Park LAK T R R N OCEANRALEIGH VIEW RD I R H E A R E PUPUKE Northcote Hauraki A 18 Y D EXMOUTH RD 2 E Scott Pt D RD L R JUTLAND RD E D A E ORAPIU RD RD S Birkenhead V I W K D E A Belmont W R A L R Hauraki Gulf I MOKO ONEWA R P IA RD D D Waitemata A HINEMOA ST Waiheke LLE RK Taniwhanui Point W PA West Harbour OLD LAKE Golf Course Pakatoa Point L E ST Chatswood BAYSWATER VAUXHALL RD U 1 Harbour QUEEN ST Bayswater RD Narrow C D Motuihe KE NS R Luckens Point Waitemata Neck Island AWAROA RD Chelsea Bay Golf Course Park Point Omiha Motorway . -

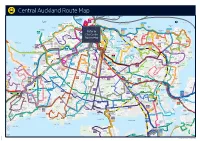

Central Auckland Route

Ferries to Central Auckland Route MapWest Harbour, Beach Haven and Devonport Hobsonville Wharf Devonport Auckland Ferry to Bayswater Ferry to Harbour Bridge Stanley Bay Westhaven Ferry to CityLink Devonport J S North Shore ellic h oe S e t ll Waitemata y t Harbourview C S B St Marys t u Beach Reserve Harbour e n rr a Ferries to Auckland o a c Ponsonby h Bay t n S m S R Ferries to Waiheke, Half Moon Bay, TāmakiLink Herne Bay t u S Britomart y Sch. d M a t e e Gulf Harbour & Pine Harbour a s B l r a y St H Te Atatu s we R ansha St Heliers d F Qua OuterLink Peninsula Jervois Rd y St Mission Bay K St Marys Bayfield Sch. e Bay l College Coxs Bay m Ponsonby Int. a r Spark Okahu Bay n a Arena TāmakiLink Kelly T TāmakiLink d Glover am R Pt Chevalier d A MJ Savage aki Dr Park Tarltons R v InnerLink i d l n e Albert Parnell Memorial Park Kohimarama C E P t Hukanui Park G Wes o d Beach Ponsonby R n l Karaka n Parnell Rose Coxs Bay Reserve Auckland ra a d t V St Heliers i s S D T ale R d R Refer to d Gardens i r a d Park ill St o W University e k m d e St Pauls O'Ne e h a Ronaki R Bay e n ll T s d aki Dr v v n li in am e k gt t T Eastclie v A A K o o College er St b d e y i Summ an n S U A l n n P l r n y r t olyg R e n g F n P Retirement n on R B Churchill R s i e a Orakei y d a l d d d e o S y l l le R a Pr R D t w d u nt S n Village t e ermo i l Park a y V R t Domain R d S r a St H F m S n a Matatu e d a t T i d i r t H Cante M l Parnell rbury Pl S e d Sch. -

Auckland Unitary Plan Operative in Part 1 6300 North Auckland Railway Line

Designation Schedule – KiwiRail Holdings Ltd Number Purpose Location 6300 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, North Auckland Railway Line from Portage railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... Road, Otahuhu to Ross Road, Topuni 6301 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Newmarket Branch Railway Line from Remuera railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... Road, Newmarket to The Strand, Parnell 6302 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, North Island Main Trunk Railway Line railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... from Buckland to Britomart Station, Auckland Central 6303 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Avondale Southdown Railway Line from Soljak railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... Place, Mount Albert to Bond Place, Onehunga 6304 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Onehunga Branch Railway Line railway infrastructure, and railway premises from Onehunga Harbour Road, Onehunga to ... Station Road, Penrose and Neilson Street, Tepapa 6305 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Southdown Freight Terminal at Neilson Street railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... (adjoins No. 345), Onehunga 6306 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Mission Bush Branch Railway Line railway infrastructure, and railway premises ... from Mission Bush Road, Glenbrook to Paerata Road, Pukekohe 6307 Develop, operate and maintain railways, railway lines, Manukau Rail Link from Lambie Drive (off- railway -

Penrose.DOC 2

Peka Totara Penrose High School Golden Jubilee 1955 –2005 Graeme Hunt Inspiration from One Tree Hill The school crest, a totara in front of the obelisk marking the grave of ‘father of Auckland’ Sir John Logan Campbell on One Tree Hill (Maungakiekie), signals the importance of the pa and reserve to Penrose High School. It was adopted in 1955 along with the Latin motto, ‘Ad Altiora Contende’, which means ‘strive for higher things’. Foundation principal Ron Stacey, a Latin scholar, described the school in 1955 as a ‘young tree groping courageously towards the skies’. ‘We look upward towards the summit of Maungakiekie where all that is finest in both Maori and Pakeha is commemorated for ever in stone and bronze,’ he wrote. In 1999 a red border was added to the crest but the crest itself remained unchanged. In 1987 the school adopted a companion logo based on the kiekie plant which grew on One Tree Hill in pre-European times (hence the Maungakiekie name). The logo arose from a meeting of teachers debating education reform where the school’s core values were identified. The words that appear on the kiekie logo provide a basis for developing the school’s identity. The kiekie, incorporated in the school’s initial charter in 1989, does not replace the crest but rather complements it. School prayer† School hymn† Almighty God, our Heavenly Father, Go forth with God! We pray that you will bless this school, Go forth with God! the day is now Guide and help those who teach, and those who learn, That thou must meet the test of youth: That together, we may seek the truth, Salvation's helm upon thy brow, And grow in understanding of ourselves and other people Go, girded with the living truth. -

The State Provision of Medicines in New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Private Interests and Public Money: The State Provision of Medicines in New Zealand 1938-1986 A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Massey University Astrid Theresa Baker 1996 Contents Abstract Preface iii Abbreviations vii 1 Medicines, Politics and Welfare States 1 2 Setting the Rules 1936-1941 27 3 Producing the Medicines 52 4 Operating the System 1941-1960 74 5 Supplying the New Zealand Market 103 6 Paying the Price 128 7 Scrutiny and Compromise 1960-1970 153 8 Holding the Status Quo 1970-1984 185 9 Changing the Rules 1984-1986 216 10 Conclusion: Past and Present 246 Bibliography 255 ,/ Abstract Provision for free medicines was one aspect of the universal health service outlined in Part III of Labour's Social Security Act 1938. The official arrangements made dUring the next three years to supply medicines under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme were intended to benefit the ill, but also protected the interests of doctors and pharmacists. The Government's introduction of these benefits coincided with dramatic advances in organic chemistry and the subsequent development of synthetic drugs in Europe and the United States. These events transformed the pharmaceutical industry from a commodity business to a sophisticated international industry producing mainly synthetic, mass-produced medicines, well protected by patents. -

New Zealand: 2020 General Election

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 9034, 26 October 2020 New Zealand: 2020 By Nigel Walker general election Antonia Garraway Contents: 1. Background 2. 2020 General Election www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 New Zealand: 2020 general election Contents Summary 3 1. Background 4 2. 2020 General Election 5 2.1 Political parties 5 2.2 Party leaders 7 2.3 Election campaign 10 2.4 Election results 10 2.5 The 53rd Parliament 11 Cover page image copyright: Jacinda Ardern reopens the Dunedin Courthouse by Ministry of Justice of New Zealand – justice.govt.nz – Wikimedia Commons page. Licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) / image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 26 October 2020 Summary New Zealand held a General Election on Saturday 17 October 2020, with advance voting beginning two weeks earlier, on 3 October. Originally planned for 19 September, the election was postponed due to Covid-19. As well as electing Members of Parliament, New Zealand’s electorate voted on two referendums: one to decriminalise the recreational use of marijuana; the other to allow some terminally ill people to request assisted dying. The election was commonly dubbed the “Covid election”, with the coronavirus pandemic the main issue for voters throughout the campaign. Jacinda Ardern, the incumbent Prime Minister from the Labour Party, had been widely praised for her handling of the pandemic and the “hard and early” plan introduced by her Government in the early stages. She led in the polls throughout the campaign. Preliminary results from the election show Ms Ardern won a landslide victory, securing 49.1 per cent of the votes and a projected 64 seats in the new (53rd) Parliament: a rare outright parliamentary majority.