Draft the 100 Most Eminent Psychologists 1 the Published

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ROMANCE of BIBLE CHRONOLOGY Rev

THE ROMANCE OF BIBLE CHRONOLOGY Rev. Martin Anstey, BA, MA An Exposition of the Meaning, and a Demonstration of the Truth, of Every Chronological Statement Contained in the Hebrew Text of the Old Testament Marshall Brothers, Ltd., London, Edinburgh and New York 1913. DEDICATION To my dear Friend Rev. G. Campbell Morgan, D.D. to whose inspiring Lectures on “The Divine Library in Human History” I trace the inception of these pages, and whose intimate knowledge and unrivalled exposition of the Written Word makes audible in human ears the Living Voice of the Living God, I dedicate this book. The Author October 3rd, 1913 FOREWORD BY REV. G. CAMPBELL MORGAN, D. D. It is with pleasure, and yet with reluctance, that I have consented to preface this book with any words of mine. The reluctance is due to the fact that the work is so lucidly done, that any setting forth of the method or purpose by way of introduction would be a work of supererogation. The pleasure results from the fact that the book is the outcome of our survey of the Historic move- ment in the redeeming activity of God as seen in the Old Testament, in the Westminster Bible School. While I was giving lectures on that subject, it was my good fortune to have the co—operation of Mr. Mar- tin Anstey, in a series of lectures on these dates. My work was that of sweeping over large areas, and largely ignoring dates. He gave his attention to these, and the result is the present volume, which is in- valuable to the Bible Teacher, on account of its completeness and detailed accuracy. -

Developmental Dynamics: Toward a Biologically Plausible Evolutionary Psychology

Psychological Bulletin Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2003, Vol. 129, No. 6, 819–835 0033-2909/03/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.819 Developmental Dynamics: Toward a Biologically Plausible Evolutionary Psychology Robert Lickliter Hunter Honeycutt Florida International University Indiana University Bloomington There has been a conceptual revolution in the biological sciences over the past several decades. Evidence from genetics, embryology, and developmental biology has converged to offer a more epigenetic, contingent, and dynamic view of how organisms develop. Despite these advances, arguments for the heuristic value of a gene-centered, predeterministic approach to the study of human behavior and development have become increasingly evident in the psychological sciences during this time. In this article, the authors review recent advances in genetics, embryology, and developmental biology that have transformed contemporary developmental and evolutionary theory and explore how these advances challenge gene-centered explanations of human behavior that ignore the complex, highly coordinated system of regulatory dynamics involved in development and evolution. The prestige of success enjoyed by the gene theory might become a evolutionary psychology assert that applying insights from evolu- hindrance to the understanding of development by directing our tionary theory to explanations of human behavior will stimulate attention solely to the genome....Already we have theories that refer more fruitful research programs and provide a powerful frame- the processes of development to genic action and regard the whole work for discovering evolved psychological mechanisms thought performance as no more than the realization of the potencies of the genes. Such theories are altogether too one-sided. -

The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20Th Century

Review of General Psychology Copyright 2002 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2002, Vol. 6, No. 2, 139–152 1089-2680/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//1089-2680.6.2.139 The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century Steven J. Haggbloom Renee Warnick, Jason E. Warnick, Western Kentucky University Vinessa K. Jones, Gary L. Yarbrough, Tenea M. Russell, Chris M. Borecky, Reagan McGahhey, John L. Powell III, Jamie Beavers, and Emmanuelle Monte Arkansas State University A rank-ordered list was constructed that reports the first 99 of the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Eminence was measured by scores on 3 quantitative variables and 3 qualitative variables. The quantitative variables were journal citation frequency, introductory psychology textbook citation frequency, and survey response frequency. The qualitative variables were National Academy of Sciences membership, election as American Psychological Association (APA) president or receipt of the APA Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and surname used as an eponym. The qualitative variables were quantified and combined with the other 3 quantitative variables to produce a composite score that was then used to construct a rank-ordered list of the most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. The discipline of psychology underwent a eve of the 21st century, the APA Monitor (“A remarkable transformation during the 20th cen- Century of Psychology,” 1999) published brief tury, a transformation that included a shift away biographical sketches of some of the more em- from the European-influenced philosophical inent contributors to that transformation. Mile- psychology of the late 19th century to the stones such as a new year, a new decade, or, in empirical, research-based, American-dominated this case, a new century seem inevitably to psychology of today (Simonton, 1992). -

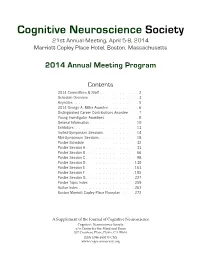

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Mental Imagery: in Search of a Theory

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2002) 25, 157–238 Printed in the United States of America Mental imagery: In search of a theory Zenon W. Pylyshyn Rutgers Center for Cognitive Science, Rutgers University, Busch Campus, Piscataway, NJ 08854-8020. [email protected] http://ruccs.rutgers.edu/faculty/pylyshyn.html Abstract: It is generally accepted that there is something special about reasoning by using mental images. The question of how it is spe- cial, however, has never been satisfactorily spelled out, despite more than thirty years of research in the post-behaviorist tradition. This article considers some of the general motivation for the assumption that entertaining mental images involves inspecting a picture-like object. It sets out a distinction between phenomena attributable to the nature of mind to what is called the cognitive architecture, and ones that are attributable to tacit knowledge used to simulate what would happen in a visual situation. With this distinction in mind, the paper then considers in detail the widely held assumption that in some important sense images are spatially displayed or are depictive, and that examining images uses the same mechanisms that are deployed in visual perception. I argue that the assumption of the spatial or depictive nature of images is only explanatory if taken literally, as a claim about how images are physically instantiated in the brain, and that the literal view fails for a number of empirical reasons – for example, because of the cognitive penetrability of the phenomena cited in its favor. Similarly, while it is arguably the case that imagery and vision involve some of the same mechanisms, this tells us very little about the nature of mental imagery and does not support claims about the pictorial nature of mental images. -

How a Cognitive Psychologist Came to Seek Universal Laws

Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2004, 11 (1), 1-23 PSYCHONOMIC SOCIETY KEYNOTE ADDRESS How a cognitive psychologist came to seek universal laws ROGERN. SHEPARD Stanford University, Stanford, California and Arizona Senior Academy, Tucson, Arizona Myearlyfascination with geometry and physics and, later, withperception and imagination inspired a hope that fundamental phenomena ofpsychology, like those ofphysics, might approximate univer sal laws. Ensuing research led me to the following candidates, formulated in terms of distances along shortestpaths in abstractrepresentational spaces: Generalization probability decreases exponentially and discrimination time reciprocally with distance. Time to determine the identity of shapes and, pro visionally, relation between musical tones or keys increases linearly with distance. Invariance of the laws is achieved by constructing the representational spaces from psychological rather than physical data (using multidimensional scaling) and from considerations of geometry, group theory, and sym metry. Universality of the laws is suggested by their behavioral approximation in cognitively advanced species and by theoretical considerations of optimality. Just possibly, not only physics but also psy chology can aspire to laws that ultimately reflect mathematical constraints, such as those ofgroup the ory and symmetry, and, so, are both universal and nonarbitrary. The object ofall science, whether natural science or psy three principal respects. The first is my predilection for chology, is to coordinate our experiences and to bring them applying mathematical ideas that are often ofa more geo into a logical system. metrical or spatial character than are the probabilistic or (Einstein, 1923a, p. 2) statistical concepts that have generally been deemed [But] the initial hypotheses become steadily more abstract most appropriate for the behavioral and social sciences. -

Experimente Clasice in Psihologie

PSIHOLOGIE - PSIHOTERAPIE Colecţie coordonată de Simona Reghintovschi DOUGLAS MOOK Experimente clasice în psihologie Traducere din engleză de Clara Ruse Prefaţă la ediţia în limba română de Mihai Aniţei A TRei Editori SILVIU DRAGOMIR VASILE DEM. ZAMFIRESCU Director editorial MAGDALENA MÂRCULESCU Coperta FABER STUDIO (S. OLTEANU, A. RĂDULESCU, D. DUMBRĂVICIAN) Redactor RALUCA HURDUC Director producţie CRISTIAN CLAUDIU COBAN Dtp MARIAN CONSTANTIN Corectori ELENA BIŢU EUGENIA URSU Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României MOOK, DOUGLAS Experimente clasice în psihologie / Douglas Mook; trad.: Clara Ruse. - Bucureşti: Editura Trei, 2009 ISBN 978-973-707-286-3 I. Ruse, Clara (trad.) 159.9 Această carte a fost tradusă după Classic Experiments in Psychology de Douglas Mook, Editura Greenwood Press, imprintal Grupului Editorial Greenwood, Westport, CT, U.S.A. (http://www.greenwood.com/greenwood_press.aspx) Copyright © 2004 by Douglas Mook Copyright © Editura Trei, 2009 pentru prezenta ediţie C.P. 27-0490, Bucureşti Tel./Fax: +4 021300 60 90 e-mail: [email protected] www.edituratrei.ro ISBN 978-973-707-286-3 în memoria lui Eliot Stellar, care ar fi -putut o scrie mai bine. Cuprins Prefaţă la ediţia română (de Prof.univ.dr. Mihai Aniţei)................................. 11 Prefaţă .............................................................................................................................. 15 Mulţumiri.........................................................................................................................17 -

Gordon Bower Papers SC1223

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8ff3z2n Online items available Guide to the Gordon Bower papers SC1223 Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Gordon Bower SC1223 1 papers SC1223 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Gordon Bower papers Creator: Bower, Gordon H. Identifier/Call Number: SC1223 Physical Description: 24.75 Linear Feet17 boxes and 6.32 GB of digital files Date (inclusive): 1950-2016 Language of Material: English Access to Collection Recommendations and student materials are closed for 75 years from date of creation. Otherwise tThe materials are open for research use. Audio-visual materials are not available in original format, and must be reformatted to a digital use copy. Publication Rights All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94305-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. See: http://library.stanford.edu/spc/using-collections/permission-publish. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Gordon Bower papers (SC1223). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. -

Ordines Militares Conference

ORDINES◆ MILITARES COLLOQUIA TORUNENSIA HISTORICA Yearbook for the Study of the Military Orders vol. XIX (2014) Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika Towarzystwo Naukowe w Toruniu Toruń 2014 Editorial Board Roman Czaja, Editor in Chief, Nicolaus Copernicus University Toruń Jürgen Sarnowsky, Editor in Chief, University of Hamburg Jochen Burgtorf, California State University Sylvain Gouguenheim, École Normale Supérieure Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Lyon Hubert Houben, Università del Salento Lecce Alan V. Murray, University of Leeds Krzysztof Kwiatkowski, Assistant Editor, Nicolaus Copernicus University Toruń Reviewers: Udo Arnold, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn (retired) Karl Borchardt, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, München Jochen Burgtorf, Department of History, California State University Wiesław Długokęcki, Institute of History, University of Gdańsk Marie-Luise Favreau-Lilie, Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut, Freie Universität Berlin Alan Forey, Durham University (retired) Mario Glauert, Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv in Potsdam Sylvain Gouguenheim, Ecole Normale Supérieure Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Lyon Dieter Heckmann, Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin-Dahlem Ilgvars Misāns, Faculty of History and Philosophy, University of Latvia, Riga Maria Starnawska, Institute of History, Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa Sławomir Zonenberg, Institute of History and International Relationships, Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz Janusz Tandecki, Institut of History and Archival Sciences, Nicolaus -

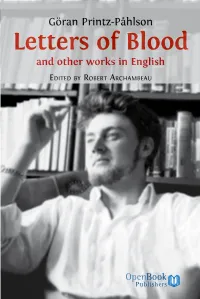

John Ashbery 125 Part Twelve the Voyages of John Matthias 133

Göran Printz-Påhlson Letters of Blood and other works in English EDITED BY ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/86 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Edited by Robert Archambeau https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2011 Robert Archambeau; Foreword © 2011 Elinor Shaffer; ‘The Overall Wandering of Mirroring Mind’: Some Notes on Göran Printz-Påhlson © 2011 Lars-Håkan Svensson; Göran Printz-Påhlson’s original texts © 2011 Ulla Printz-Påhlson. Version 1.2. Minor edits made, May 2016. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Göran Printz-Påhlson, Robert Archambeau (ed.), Letters of Blood. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0017 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. openbookpublishers.com/product/86#copyright Further details about CC BY-NC-ND licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/ All the external links were active on 02/5/2016 unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume can be found at https://www. -

GRE Vocabulary

Table of Contents Introduction About Us What is Magoosh? Featured in Why Our Students Love Us How to Use Vocabulary Lists Timmy’s Vocabulary Lists Shirley’s Vocabulary Lists Timmy’s Triumph Takeway Making Words Stick: Memorizing GRE Vocabulary Come up with Clever (and Wacky) Associations Use It or Lose It Do Not Bite Off More Than You Can Chew Read to Be Surprised Takeaways Most Common GRE Words Top 10 GRE Words of 2012 Top 5 Basic GRE Words Common Words that Students Always Get Wrong Tricky “Easy” GRE Words with Multiple Meanings Commonly Confused Sets Interesting (and International) Word Origins Around the World French Words Eponyms Words with Strange Origins Themed Lists Vocab from Within People You Wouldn’t Want To Meet Religious Words Words from Political Scandals Money Matters: How Much Can You Spend? Money Matters: Can’t Spend it Fast Enough Money Matters: A Helping (or Thieving!) Hand Vocabulary from up on High Preposterous Prepositions Them’s Fighting Words gre.magoosh.com 1 Animal Mnemonics Webster’s Favorites “Occupy” Vocabulary Compound Words Halloween Vocabulary Talkative Words By the Letter A-Words C-Words Easily Confusable F-Words Vicious Pairs of V’s “X” words High-Difficulty Words Negation Words: Misleading Roots Difficult Words that the GRE Loves to Use Re- Doesn’t Always Mean Again GRE Vocabulary Books: Recommended Fiction and Non-Fiction The Best American Series The Classics Takeaway Vocabulary in Context: Articles from Magazines and Newspapers The Atlantic Monthly The New Yorker New York Times Book Review The New York Times Practice Questions Sentence Equivalence Text Completion Reading Comprehension GRE Vocabulary: Free Resources on the Internet gre.magoosh.com 2 Introduction This eBook is a compilation of the most popular Revised GRE vocabulary word list posts from the Magoosh GRE blog. -

Magooshgrevocabebook.Pdf

Updated 1/15/13 1 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 About Us ................................................................................................................... 4 What is Magoosh? ...................................................................................................... 4 Featured in ............................................................................................................. 4 Why Our Students Love Us ........................................................................................... 5 How to Use Vocabulary Lists ........................................................................................... 7 Timmy’s Vocabulary Lists ............................................................................................ 7 Shirley’s Vocabulary Lists ............................................................................................ 7 Timmy’s Triumph ...................................................................................................... 8 Takeway ................................................................................................................. 8 Making Words Stick: Memorizing GRE Vocabulary................................................................... 9 Come up with Clever (and Wacky) Associations .................................................................. 9 Use It or Lose It .......................................................................................................