Experimente Clasice in Psihologie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All in the Mind Psychology for the Curious

All in the Mind Psychology for the Curious Third Edition Adrian Furnham and Dimitrios Tsivrikos www.ebook3000.com This third edition first published 2017 © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd Edition history: Whurr Publishers Ltd (1e, 1996); Whurr Publishers Ltd (2e, 2001) Registered Office John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148‐5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley‐blackwell. The right of Adrian Furnham and Dimitrios Tsivrikos to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

The Lived Economics of Love and a Spirituality for Every Day: Wealth Inequality, Anthropology, and Motivational Theory After Harlow’S Monkeys

The Lived Economics of Love and a Spirituality for Every Day: Wealth Inequality, Anthropology, and Motivational Theory after Harlow’s Monkeys Christian Early Introduction The current inequality of wealth is at an all-time high, and the best estimates indicate that inequality will only increase in future. This is true not only in North America but globally as well. A recent Global Wealth Report states that less than one percent of the world’s adult population own just below forty percent of global household wealth.1 In America, the top quintile own eighty-four percent of the country’s wealth, while the lower two quintiles combined own less than one percent of it.2 What are we to make of the widening gap between rich and poor? What, if anything, does it say about who we are as human beings? In The Heart of L’Arche: A Spirituality for Every Day, Jean Vanier proposes a spirituality centered on what he calls “the mystery of the poor.”3 All human beings carry a burden of brokenness and deep needs, he argues, which cries out for healing through friendship. The real difference between the rich and the poor, aside from their financial status which is in plain sight, is that the rich are capable of hiding their brokenness from others and from themselves. It is difficult for them to own their own (true) poverty. The poor, by contrast, cannot hide it; they know too well that they are trapped in a broken self-image and stand in need of others. The acknowledgment of their situation—their inability to hide their predicament from themselves—is their gift. -

Concepts As Correlates of Lexical Labels. a Cognitivist Perspective

This is a submitted manuscript version. The publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form. Final published version, copyright Peter Lang: https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-05287-9 Sławomir Wacewicz Concepts as Correlates of Lexical Labels. A Cognitivist Perspective. This is a submitted manuscript version. The publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form. Final published version, copyright Peter Lang: https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-05287-9 CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………... 6 PART I INTERNALISTIC PERSPECTIVE ON LANGUAGE IN COGNITIVE SCIENCE Preliminary remarks………………………………………………………… 17 1. History and profile of Cognitive Science……………………………….. 18 1.1. Introduction…………………………………………………………. 18 1.2. Cognitive Science: definitions and basic assumptions ……………. 19 1.3. Basic tenets of Cognitive 22 Science…………………………………… 1.3.1. Cognition……………………………………………………... 23 1.3.2. Representationism and presentationism…………………….... 25 1.3.3. Naturalism and physical character of mind…………………... 28 1.3.4. Levels of description…………………………………………. 30 1.3.5. Internalism (Individualism) ………………………………….. 31 1.4. History……………………………………………………………... 34 1.4.1. Prehistory…………………………………………………….. 35 1.4.2. Germination…………………………………………………... 36 1.4.3. Beginnings……………………………………………………. 37 1.4.4. Early and classical Cognitive Science………………………… 40 1.4.5. Contemporary Cognitive Science……………………………... 42 1.4.6. Methodological notes on interdisciplinarity………………….. 52 1.5. Summary…………………………………………………………. 59 2. Intrasystemic and extrasystemic principles of concept individuation 60 2.1. Existential status of concepts ……………………………………… 60 2 This is a submitted manuscript version. The publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form. Final published version, copyright Peter Lang: https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-05287-9 2.1.1. -

Developmental Dynamics: Toward a Biologically Plausible Evolutionary Psychology

Psychological Bulletin Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2003, Vol. 129, No. 6, 819–835 0033-2909/03/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.819 Developmental Dynamics: Toward a Biologically Plausible Evolutionary Psychology Robert Lickliter Hunter Honeycutt Florida International University Indiana University Bloomington There has been a conceptual revolution in the biological sciences over the past several decades. Evidence from genetics, embryology, and developmental biology has converged to offer a more epigenetic, contingent, and dynamic view of how organisms develop. Despite these advances, arguments for the heuristic value of a gene-centered, predeterministic approach to the study of human behavior and development have become increasingly evident in the psychological sciences during this time. In this article, the authors review recent advances in genetics, embryology, and developmental biology that have transformed contemporary developmental and evolutionary theory and explore how these advances challenge gene-centered explanations of human behavior that ignore the complex, highly coordinated system of regulatory dynamics involved in development and evolution. The prestige of success enjoyed by the gene theory might become a evolutionary psychology assert that applying insights from evolu- hindrance to the understanding of development by directing our tionary theory to explanations of human behavior will stimulate attention solely to the genome....Already we have theories that refer more fruitful research programs and provide a powerful frame- the processes of development to genic action and regard the whole work for discovering evolved psychological mechanisms thought performance as no more than the realization of the potencies of the genes. Such theories are altogether too one-sided. -

The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20Th Century

Review of General Psychology Copyright 2002 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2002, Vol. 6, No. 2, 139–152 1089-2680/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//1089-2680.6.2.139 The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century Steven J. Haggbloom Renee Warnick, Jason E. Warnick, Western Kentucky University Vinessa K. Jones, Gary L. Yarbrough, Tenea M. Russell, Chris M. Borecky, Reagan McGahhey, John L. Powell III, Jamie Beavers, and Emmanuelle Monte Arkansas State University A rank-ordered list was constructed that reports the first 99 of the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Eminence was measured by scores on 3 quantitative variables and 3 qualitative variables. The quantitative variables were journal citation frequency, introductory psychology textbook citation frequency, and survey response frequency. The qualitative variables were National Academy of Sciences membership, election as American Psychological Association (APA) president or receipt of the APA Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and surname used as an eponym. The qualitative variables were quantified and combined with the other 3 quantitative variables to produce a composite score that was then used to construct a rank-ordered list of the most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. The discipline of psychology underwent a eve of the 21st century, the APA Monitor (“A remarkable transformation during the 20th cen- Century of Psychology,” 1999) published brief tury, a transformation that included a shift away biographical sketches of some of the more em- from the European-influenced philosophical inent contributors to that transformation. Mile- psychology of the late 19th century to the stones such as a new year, a new decade, or, in empirical, research-based, American-dominated this case, a new century seem inevitably to psychology of today (Simonton, 1992). -

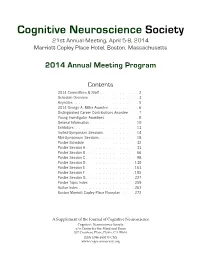

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Mental Imagery: in Search of a Theory

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2002) 25, 157–238 Printed in the United States of America Mental imagery: In search of a theory Zenon W. Pylyshyn Rutgers Center for Cognitive Science, Rutgers University, Busch Campus, Piscataway, NJ 08854-8020. [email protected] http://ruccs.rutgers.edu/faculty/pylyshyn.html Abstract: It is generally accepted that there is something special about reasoning by using mental images. The question of how it is spe- cial, however, has never been satisfactorily spelled out, despite more than thirty years of research in the post-behaviorist tradition. This article considers some of the general motivation for the assumption that entertaining mental images involves inspecting a picture-like object. It sets out a distinction between phenomena attributable to the nature of mind to what is called the cognitive architecture, and ones that are attributable to tacit knowledge used to simulate what would happen in a visual situation. With this distinction in mind, the paper then considers in detail the widely held assumption that in some important sense images are spatially displayed or are depictive, and that examining images uses the same mechanisms that are deployed in visual perception. I argue that the assumption of the spatial or depictive nature of images is only explanatory if taken literally, as a claim about how images are physically instantiated in the brain, and that the literal view fails for a number of empirical reasons – for example, because of the cognitive penetrability of the phenomena cited in its favor. Similarly, while it is arguably the case that imagery and vision involve some of the same mechanisms, this tells us very little about the nature of mental imagery and does not support claims about the pictorial nature of mental images. -

How a Cognitive Psychologist Came to Seek Universal Laws

Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2004, 11 (1), 1-23 PSYCHONOMIC SOCIETY KEYNOTE ADDRESS How a cognitive psychologist came to seek universal laws ROGERN. SHEPARD Stanford University, Stanford, California and Arizona Senior Academy, Tucson, Arizona Myearlyfascination with geometry and physics and, later, withperception and imagination inspired a hope that fundamental phenomena ofpsychology, like those ofphysics, might approximate univer sal laws. Ensuing research led me to the following candidates, formulated in terms of distances along shortestpaths in abstractrepresentational spaces: Generalization probability decreases exponentially and discrimination time reciprocally with distance. Time to determine the identity of shapes and, pro visionally, relation between musical tones or keys increases linearly with distance. Invariance of the laws is achieved by constructing the representational spaces from psychological rather than physical data (using multidimensional scaling) and from considerations of geometry, group theory, and sym metry. Universality of the laws is suggested by their behavioral approximation in cognitively advanced species and by theoretical considerations of optimality. Just possibly, not only physics but also psy chology can aspire to laws that ultimately reflect mathematical constraints, such as those ofgroup the ory and symmetry, and, so, are both universal and nonarbitrary. The object ofall science, whether natural science or psy three principal respects. The first is my predilection for chology, is to coordinate our experiences and to bring them applying mathematical ideas that are often ofa more geo into a logical system. metrical or spatial character than are the probabilistic or (Einstein, 1923a, p. 2) statistical concepts that have generally been deemed [But] the initial hypotheses become steadily more abstract most appropriate for the behavioral and social sciences. -

Consciousness Is a Thing, Not a Process

applied sciences Opinion Consciousness Is a Thing, Not a Process Susan Pockett School of Psychology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand; [email protected] Received: 30 October 2017; Accepted: 23 November 2017; Published: 2 December 2017 Featured Application: If the theory outlined here is correct, the construction of artificial consciousness will certainly be possible, but a fundamentally different approach from that currently used in work on artificial intelligence will be necessary. Abstract: The central dogma of cognitive psychology is ‘consciousness is a process, not a thing’. Hence, the main task of cognitive neuroscientists is generally seen as working out what kinds of neural processing are conscious and what kinds are not. I argue here that the central dogma is simply wrong. All neural processing is unconscious. The illusion that some of it is conscious results largely from a failure to separate consciousness per se from a number of unconscious processes that normally accompany it—most particularly focal attention. Conscious sensory experiences are not processes at all. They are things: specifically, spatial electromagnetic (EM) patterns, which are presently generated only by ongoing unconscious processing at certain times and places in the mammalian brain, but which in principle could be generated by hardware rather than wetware. The neurophysiological mechanisms by which putatively conscious EM patterns are generated, the features that may distinguish conscious from unconscious patterns, the general principles that distinguish the conscious patterns of different sensory modalities and the general features that distinguish the conscious patterns of different experiences within any given sensory modality are all described. Suggestions for further development of this paradigm are provided. -

AP Psychology Summer Assignment Griffin Cook Mary Ainsworth: Mary

AP Psychology Summer Assignment Griffin Cook Mary Ainsworth: Mary Ainsworth was involved in the study of attachment between a child and their caregiver. She designed an experiment called the Strange Situation to test the attachment between a baby and its caregiver. From her experiment, she determined that there are three types of attachment a baby may have with their caregiver: Mary Ainsworth’s Attachment Theory Secure Attachment, Anxious- Ambivalent Insecure Attachment, and Anxious-Avoidant Insecure Attachment. Commented [WPB1]: 4 excellent Solomon Asch: Asch worked in the field of social psychology and studied several subjects, such as prestige suggestion, impression formation, and conformity. One of his most famous experiments demonstrated conformity, and involved estimating the length of lines. In the experiment, some people would intentionally make false estimates as to the length of the lines, and usually the actual test subjects would change their estimate to more closely resemble the false estimates made by the other people. Commented [WPB2]: 4 Albert Bandura: Albert Bandura developed social learning theory. He stated that learning takes place through more than just reinforcement, and that people learn by imitation, or modeling. His famous Bobo doll study demonstrated this idea well. In his experiment he would show a video of a woman beating a doll to a group of children. He would then let the children play in a room that had that same doll, and the children consistently began beating the doll. Commented [WPB3]: 4 Walter Cannon: Canon researched the instinctual repulsion from danger on animals. He worked with laboratory animals, and noticed that when they were stressed there were changes in their digestive systems. -

Released Textbooks, Films and Other Teaching Materials. INSTITUTION National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 054 946 SE 012 377 TITLE Released Textbooks, Films and Other Teaching Materials. INSTITUTION National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Jul 68 NOTE 75p. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. EDRS PRICE BF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Bibliographies; College Programs; Elementary Education; Films; *Instructional Materials;*Science Course Improvement Project; SecondaryEducation; *Social Sciences IDENTIFIERS *National Science Foundation ABSTRACT Some course and curriculum improvementprojects funded by the National Science Foundation haveproduced definitive editions of textbooks, other printed materials, andinstructional films. This bulletin lists materials availablein 1968 through commercial or college and university sources. Thepublications include textbooks, laboratory guides, teachers'guides, supplementary readings for students and teachers, and sourcebooks.Materials are grouped by educational level (elementaryand secoudary school; college and university), and, within each level,by discipline (multidisciplinary, earth sciences, biology, chemistry,mathematics, physics, engineering, and social sciences).Citations include the project title, grantee, project director (1968),publishers of books and films, and 1968 prices. (Author/AL) US. DEPARTMENT OFHEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATIO N BEEN REPRO- i THIS DOCUMENT HAS ; DUCED EXACTLY ASRECEIVED FROM ORGANIZATION ORIG- THE PERSON OR INATING IT. POINTS OFVIEW OR OPIN- National Science Foundation -

Welcome to AP Psychology! – 2019 SUMMER ASSIGNMENT

Welcome to AP Psychology! – 2019 SUMMER ASSIGNMENT I am ecstatic that you have decided to join this class and chose to challenge yourself with the fascinating world of psychology. I am certain that you will find this course worthwhile and personally relevant. Although it is the summer, there is work to be done. Please note, AP Psychology is an elective, college-level course with higher student expectations than most courses taken by high school students. With that being said, it is imperative that we get a jump start on the AP Psychology curriculum. It is mandatory and, in your best interest to complete the summer assignment. Your summer assignment is comprised of THREE mini-assignments. Each assignment will serve a specific purpose that will assist you throughout the school year and aid in your preparations for the AP Exam in May. The following assignment is due by August 12. Please send all answers for Part 2 and 3 typed in a Word or Google document, electronically (via email) to Mrs. Schwan: [email protected]. You may also share your document via Google drive to the same email address. Part 1 will be submitted to Mrs. Schwan by 3:10 August 12. Summer Assignment #1 – “ Who’s Who?” Create Your Cards! Names to Know for the AP Psychology Exam Directions: You will create a set of baseball style cards for the 24 most influential Psychologists. Using either Wikipedia (not my favorite, but they are all there with all of the information you will need) or another search engine of your choice, look up each of the names below and complete a bit of research about each of these influential psychologists.