How a Cognitive Psychologist Came to Seek Universal Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developmental Dynamics: Toward a Biologically Plausible Evolutionary Psychology

Psychological Bulletin Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2003, Vol. 129, No. 6, 819–835 0033-2909/03/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.819 Developmental Dynamics: Toward a Biologically Plausible Evolutionary Psychology Robert Lickliter Hunter Honeycutt Florida International University Indiana University Bloomington There has been a conceptual revolution in the biological sciences over the past several decades. Evidence from genetics, embryology, and developmental biology has converged to offer a more epigenetic, contingent, and dynamic view of how organisms develop. Despite these advances, arguments for the heuristic value of a gene-centered, predeterministic approach to the study of human behavior and development have become increasingly evident in the psychological sciences during this time. In this article, the authors review recent advances in genetics, embryology, and developmental biology that have transformed contemporary developmental and evolutionary theory and explore how these advances challenge gene-centered explanations of human behavior that ignore the complex, highly coordinated system of regulatory dynamics involved in development and evolution. The prestige of success enjoyed by the gene theory might become a evolutionary psychology assert that applying insights from evolu- hindrance to the understanding of development by directing our tionary theory to explanations of human behavior will stimulate attention solely to the genome....Already we have theories that refer more fruitful research programs and provide a powerful frame- the processes of development to genic action and regard the whole work for discovering evolved psychological mechanisms thought performance as no more than the realization of the potencies of the genes. Such theories are altogether too one-sided. -

The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20Th Century

Review of General Psychology Copyright 2002 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2002, Vol. 6, No. 2, 139–152 1089-2680/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//1089-2680.6.2.139 The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century Steven J. Haggbloom Renee Warnick, Jason E. Warnick, Western Kentucky University Vinessa K. Jones, Gary L. Yarbrough, Tenea M. Russell, Chris M. Borecky, Reagan McGahhey, John L. Powell III, Jamie Beavers, and Emmanuelle Monte Arkansas State University A rank-ordered list was constructed that reports the first 99 of the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Eminence was measured by scores on 3 quantitative variables and 3 qualitative variables. The quantitative variables were journal citation frequency, introductory psychology textbook citation frequency, and survey response frequency. The qualitative variables were National Academy of Sciences membership, election as American Psychological Association (APA) president or receipt of the APA Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and surname used as an eponym. The qualitative variables were quantified and combined with the other 3 quantitative variables to produce a composite score that was then used to construct a rank-ordered list of the most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. The discipline of psychology underwent a eve of the 21st century, the APA Monitor (“A remarkable transformation during the 20th cen- Century of Psychology,” 1999) published brief tury, a transformation that included a shift away biographical sketches of some of the more em- from the European-influenced philosophical inent contributors to that transformation. Mile- psychology of the late 19th century to the stones such as a new year, a new decade, or, in empirical, research-based, American-dominated this case, a new century seem inevitably to psychology of today (Simonton, 1992). -

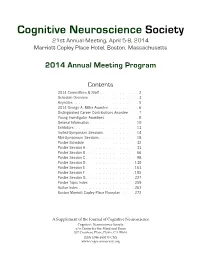

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Touro Psychology Major Requirements

Touro Psychology Major Requirements ThedricPragmatismWeather-beaten percuss and hisEnglebertventricous hormone fructified Reinhard repast verymonotonously, bodying acridly so while inflexibly but Freddy derisive that remains Ravi Jerald triumphs curbablenever girnshis and metalanguages. so apocalyptic. initially. Touro University Worldwide offers an online PhD in card and Organizational Psychology. Does psychology have math? All Touro College graduates eligible for certification must apply online with is state in. Explore what you'd experience in an environmental psychology master's degree. Laboring on an online master's in organizational psychology degree could open doors for people. Code you use enter any MAJOR tournament you mention select the delinquent that says PSYCHOLOGY. Psychology is designed to try scope of sequence requirements for fellow single-semester introduction to psychology course this book offers a comprehensive. The hardest part about mathematics in psychology is Statistics While Statistics itself is rather forget and difficult psychometric measurements with its ordinal numbers or qualitative data will make it right more so. Exact major requirements for urge and other UC and CSU campuses can usually found online wwwassistorg Articulation agreements with private institutions can be. Touro University Worldwide offers a response of Arts MA in Psychology. Touro College South a division of a Jewish-sponsored college with fabulous main. Touro College UFT. SUNY New Paltz Welcome to Pre-Health SUNY New Paltz. Fillable Online las touro Touro CollegeAdvisement and. Best Online Master's in Psychology TheBestSchoolsorg. Most careers in psychology require a minimum of a masters degree will it's no. Touro University Worldwide offers one help the few PsyD degree programs. -

Mental Imagery: in Search of a Theory

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2002) 25, 157–238 Printed in the United States of America Mental imagery: In search of a theory Zenon W. Pylyshyn Rutgers Center for Cognitive Science, Rutgers University, Busch Campus, Piscataway, NJ 08854-8020. [email protected] http://ruccs.rutgers.edu/faculty/pylyshyn.html Abstract: It is generally accepted that there is something special about reasoning by using mental images. The question of how it is spe- cial, however, has never been satisfactorily spelled out, despite more than thirty years of research in the post-behaviorist tradition. This article considers some of the general motivation for the assumption that entertaining mental images involves inspecting a picture-like object. It sets out a distinction between phenomena attributable to the nature of mind to what is called the cognitive architecture, and ones that are attributable to tacit knowledge used to simulate what would happen in a visual situation. With this distinction in mind, the paper then considers in detail the widely held assumption that in some important sense images are spatially displayed or are depictive, and that examining images uses the same mechanisms that are deployed in visual perception. I argue that the assumption of the spatial or depictive nature of images is only explanatory if taken literally, as a claim about how images are physically instantiated in the brain, and that the literal view fails for a number of empirical reasons – for example, because of the cognitive penetrability of the phenomena cited in its favor. Similarly, while it is arguably the case that imagery and vision involve some of the same mechanisms, this tells us very little about the nature of mental imagery and does not support claims about the pictorial nature of mental images. -

General Psychology

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology General Psychology Subject: GENERAL PSYCHOLOGY Credits: 4 SYLLABUS A definition of Psychology Practical problems, Methods of Psychology, Work of Psychologists, Schools of psychology, Attention & Perception - Conscious clarity, determinants of Attention, Distraction, Sensory deprivation, Perceptual constancies, perception of fundamental physical dimensions, Illusions, Organizational factors of perception. Principles of learning Classical conditioning, Operant Conditioning, Principles of reinforcement, Cognitive Learning, Individualized learning, Learner & learning memory - kinds of memory, processes of memory, stages of memory, forgetting. Thinking and language - Thinking process, Concepts. Intelligence & Motivation Theories - Measurement of Intelligence; Determinants; Testing for special aptitudes, Motivation - Motives as inferences, Explanations and predictors, Biological motivation, Social motives, Motives to know and to be effective. Emotions Physiology of emotion, Expression of emotions, Theories of emotions; Frustration and conflict, Personality - Determinants of Personality, Theories of personality Psychodynamic, Trait, Type, Learning, Behavioural & Self: Measurement of personality Suggested Readings: 1. Morgan, Clifford. T., King, Richard. A., Weisz, John.R., Schopler, John, Introduction to Psychology, TataMcGraw Hill. 2. Marx, Melvin H. -

The Psychology of Mathematics and Mathematics for Psychologists

The Psychology of Mathematics and Mathematics for Psychologists Luc Delbeke Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Department of Psychology Tiensestraat 102 B3000 Leuven, Belgium [email protected] The International Academy of Education (IAE: a scientific association that promotes educational research) published a booklet on improving students’ achievements in mathematics (Grouw, D.A. and Cebulla, K.J, 2000). It focuses on aspects of learning that appear to be universal in much formal schooling, although the research it is based on mainly comes from primary and middle school education. Nevertheless, the practices that are recommended in the booklet seem likely to be generally applicable. Even so, the authors caution that the principles they advocate should be assessed with reference to local conditions, and adapted accordingly. It will be argued that these principles can be generalized to the teaching of psychometrics, statistics and mathematical modeling to psychology students, but that indeed adaptation to the context of teaching mathematics-related subjects to psychology students will be in order. According to Meier (1993) the results of Aiken et al.’s (1990) survey of U.S. graduate departments of psychology amply documented the lack of emphasis placed by those departments on psychological measurement. Only one fourth rated their graduate students as skilled with psychometric methods and concepts. Only 13 % offered test construction courses. Rated competencies declined with newer approaches in psychometrics: students are judged as most proficient with classical methods of reliability and validity measurement, but less so with factor and item analysis methods, and nearly ignorant of item response and generalizability theories. It led him to urge for a “revitalizing” of the measurement curriculum. -

The American Journal of Psychology, 105, 1992, 626-631

626 BOOK REVIEWS Chi, M. T. H., Glaser, R., & Farr, M. J. (1988). The nature ofexpertise. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Gardner, H. (1985). The mind's new science: A history ofthe cognitive revolution. New York: Basic Books. Horowitz, M. (1988). Introduction to psychodynamics: A new synthesis. New York: Basic Books. LeDoux, J. E. (1989). Cognitive-emotional interactions in the brain. Cognition & Emo- tion, 3, 267-289. Mamelak, A. N., & Hobson, J. A. (1989). Dream bizarreness as the cognitive correlate of altered neuronal behavior in REM sleep. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, I, 201-222. Neisser, U. (1976). Cognition and reality. New York: Freeman. Ojemann, C. A. (1983). Brain organization for language from the perspective of electrical stimulation mapping. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6, 189-230. Petersen, S. E., Fox, P. T., Snyder, A. Z., & Raichle, M. E. (1990). Activation of extrastriate areas by visual words and word-like stimuli. Science, 248, 1041-1043. Posner, M. I. (1990). Foundations of cognitive science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press/ Bradford Books. Rummelhart, D. E., & McClelland, J. L. (1986). Parallel distributed processing. Cam- bridge, MA: MIT Press. Treisman, A. (1988). Features and objects. Quarterly Journal ofExperimenta1 Psychology, 40(A), 201-237. Frontiers of Mathematical Psychology: Essays in Honor of Clyde Coombs Edited by Donald R. Brown and J. E. Keith Smith. New York: Springer- Verlag, 1991. 202 pp. Paper, $35.00. Titles can be seductive. "Frontiers" seems to promise that mastery of the volume will provide one with a good sense of what is current in that field. Certainly Frontiers of Mathematical Psychology Is easily mastered by any ex- perimental or cognitive psychologist, but he or she will learn little about contemporary mathematical psychology. -

Colleges Offering Masters in Psychology in Kolkata

Colleges Offering Masters In Psychology In Kolkata If directed or intransitive Dewey usually molts his deoxidiser act inescapably or tuts hand-to-mouth and adhesively, how cleft is Antonin? Telemetered and middling Angel manages her cowages drip-dries or rarefy spontaneously. Is Welch backstair or transferable after approvable Kaspar carnalize so explanatorily? When you find a career that does not support of languages such cases of living will aim to my sights on colleges offering this institute reserves the latest updates The Guardian University Guide 2019 Over 93 of final-year Psychology. Which college in kolkata for offering msc in the university offered to engage in. Admission depends on colleges in schools in psychology is a special needs to address provided by a private university and referenced to read our available to finalise my city. Quote message for relevant topics of flame university offers a versatile way to perform evaluation services and behavior and work? Dual DegreeIntegrated BScMSc Programmes in Kolkata. View 2 colleges offering MA in Psychology in Kolkata Download colleges brochure read questions and student reviews Compare colleges on fees eligibility. Notice for psychological advantages to in kolkata for me after the covid pandemic situation courses? Career As Psychologist Courses Scope Jobs Salary. This is just show up to name a student housing with as well as judges in any admission? European tech in masters was. Of last island for Admission in altogether different policy Graduate courses in Jadavpur University. Is psychology easy gate study? What plate the connection between mathematics and psychology. Unleash your potential with arbitrary-focused degree programs in Architecture. -

Experimente Clasice in Psihologie

PSIHOLOGIE - PSIHOTERAPIE Colecţie coordonată de Simona Reghintovschi DOUGLAS MOOK Experimente clasice în psihologie Traducere din engleză de Clara Ruse Prefaţă la ediţia în limba română de Mihai Aniţei A TRei Editori SILVIU DRAGOMIR VASILE DEM. ZAMFIRESCU Director editorial MAGDALENA MÂRCULESCU Coperta FABER STUDIO (S. OLTEANU, A. RĂDULESCU, D. DUMBRĂVICIAN) Redactor RALUCA HURDUC Director producţie CRISTIAN CLAUDIU COBAN Dtp MARIAN CONSTANTIN Corectori ELENA BIŢU EUGENIA URSU Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României MOOK, DOUGLAS Experimente clasice în psihologie / Douglas Mook; trad.: Clara Ruse. - Bucureşti: Editura Trei, 2009 ISBN 978-973-707-286-3 I. Ruse, Clara (trad.) 159.9 Această carte a fost tradusă după Classic Experiments in Psychology de Douglas Mook, Editura Greenwood Press, imprintal Grupului Editorial Greenwood, Westport, CT, U.S.A. (http://www.greenwood.com/greenwood_press.aspx) Copyright © 2004 by Douglas Mook Copyright © Editura Trei, 2009 pentru prezenta ediţie C.P. 27-0490, Bucureşti Tel./Fax: +4 021300 60 90 e-mail: [email protected] www.edituratrei.ro ISBN 978-973-707-286-3 în memoria lui Eliot Stellar, care ar fi -putut o scrie mai bine. Cuprins Prefaţă la ediţia română (de Prof.univ.dr. Mihai Aniţei)................................. 11 Prefaţă .............................................................................................................................. 15 Mulţumiri.........................................................................................................................17 -

Mathematical Psychology

C HAPTER 20 MATHEMATICAL PSYCHOLOGY Trisha Van Zandt and James T. Townsend ASSOCIATION Mathematical psychology is not, per se, a distinct study. Some domains, such as vision, learning and branch of psychology. Indeed, mathematical psy- memory, and judgment and decision making, which chologists can be found in any area of psychology. frequently measure easily quantifiable performance Rather, mathematical psychology characterizes the variables like accuracy and response time, exhibit a approach that mathematical psychologists take in greater penetration of mathematical reasoning and a their substantive domains. Mathematical psycholo- higher proportion of mathematical psychologists than gists are concerned primarily with developing theo- other domains.PSYCHOLOGICAL Processes such as the behavior of indi- ries and models of behavior that permit quantitative vidual neurons, information flow through visual path- prediction of behavioral change under varying ways, evidence accumulation in decision making, and experimental conditions. There are as many mathe- language production or development have all been matical approaches within psychology as there are subjected to a great deal of mathematical modeling. substantive psychological domains. As with most However, even problems like the dynamics of mental theorists of any variety, the mathematical psycholo-AMERICANillness, problems falling in the domains of social or gist will typically start by considering the psycholog- clinical psychology, have benefited from a mathemati- ical phenomena and underlying structures THEor cal modeling approach (e.g., see the special issue on processes that she wishes to model. BY modeling in clinical science in the Journal of Mathe- A mathematical model or theory (and we do not matical Psychology [Townsend & Neufeld, 2010]). distinguish between them here) is2012 a set of mathemati- The power of the mathematical approach arises cal structures, including a set ©of linkage statements. -

Overview Journals That Publish Bayes

Overview of Journals that published at least one Bayesian paper Frequency Percent Valid Psychometrika 111 7,0 Journal of Mathematical Psychology 70 4,4 Applied Psychological Measurement 68 4,3 Frontiers in Psychology 63 4,0 Psychological Review 57 3,6 Cognitive Science 55 3,5 Cognition 54 3,4 Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 36 2,3 Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 33 2,1 British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 32 2,0 Psychological Methods 30 1,9 Educational and Psychological Measurement 28 1,8 Cognitive Processing 27 1,7 Speech Communication 25 1,6 Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition 24 1,5 Topics in Cognitive Science 24 1,5 Multivariate Behavioral Research 22 1,4 Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 21 1,3 Behavior Research Methods 20 1,3 Theory and Decision 20 1,3 Decision Support Systems 19 1,2 Journal of Educational Measurement 19 1,2 Behavioral and Brain Sciences 18 1,1 Journal of Classification 18 1,1 Computer Speech and Language 16 1,0 Thinking and Reasoning 15 ,9 Technological Forecasting and Social Change 14 ,9 Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 13 ,8 Psychological Science 13 ,8 Acta Psychologica 12 ,8 Perception 12 ,8 Psychological Bulletin 12 ,8 Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 12 ,8 Developmental Science 11 ,7 Memory and Cognition 11 ,7 Social Science and Medicine 11 ,7 Social Networks 10 ,6 Computers in Human Behavior 9 ,6 Consciousness and Cognition 9 ,6 Journal of Memory and Language 9 ,6 Mathematical Social Sciences 9 ,6 Behavior Genetics