Andrew University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ROMANCE of BIBLE CHRONOLOGY Rev

THE ROMANCE OF BIBLE CHRONOLOGY Rev. Martin Anstey, BA, MA An Exposition of the Meaning, and a Demonstration of the Truth, of Every Chronological Statement Contained in the Hebrew Text of the Old Testament Marshall Brothers, Ltd., London, Edinburgh and New York 1913. DEDICATION To my dear Friend Rev. G. Campbell Morgan, D.D. to whose inspiring Lectures on “The Divine Library in Human History” I trace the inception of these pages, and whose intimate knowledge and unrivalled exposition of the Written Word makes audible in human ears the Living Voice of the Living God, I dedicate this book. The Author October 3rd, 1913 FOREWORD BY REV. G. CAMPBELL MORGAN, D. D. It is with pleasure, and yet with reluctance, that I have consented to preface this book with any words of mine. The reluctance is due to the fact that the work is so lucidly done, that any setting forth of the method or purpose by way of introduction would be a work of supererogation. The pleasure results from the fact that the book is the outcome of our survey of the Historic move- ment in the redeeming activity of God as seen in the Old Testament, in the Westminster Bible School. While I was giving lectures on that subject, it was my good fortune to have the co—operation of Mr. Mar- tin Anstey, in a series of lectures on these dates. My work was that of sweeping over large areas, and largely ignoring dates. He gave his attention to these, and the result is the present volume, which is in- valuable to the Bible Teacher, on account of its completeness and detailed accuracy. -

The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20Th Century

Review of General Psychology Copyright 2002 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2002, Vol. 6, No. 2, 139–152 1089-2680/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//1089-2680.6.2.139 The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century Steven J. Haggbloom Renee Warnick, Jason E. Warnick, Western Kentucky University Vinessa K. Jones, Gary L. Yarbrough, Tenea M. Russell, Chris M. Borecky, Reagan McGahhey, John L. Powell III, Jamie Beavers, and Emmanuelle Monte Arkansas State University A rank-ordered list was constructed that reports the first 99 of the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Eminence was measured by scores on 3 quantitative variables and 3 qualitative variables. The quantitative variables were journal citation frequency, introductory psychology textbook citation frequency, and survey response frequency. The qualitative variables were National Academy of Sciences membership, election as American Psychological Association (APA) president or receipt of the APA Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and surname used as an eponym. The qualitative variables were quantified and combined with the other 3 quantitative variables to produce a composite score that was then used to construct a rank-ordered list of the most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. The discipline of psychology underwent a eve of the 21st century, the APA Monitor (“A remarkable transformation during the 20th cen- Century of Psychology,” 1999) published brief tury, a transformation that included a shift away biographical sketches of some of the more em- from the European-influenced philosophical inent contributors to that transformation. Mile- psychology of the late 19th century to the stones such as a new year, a new decade, or, in empirical, research-based, American-dominated this case, a new century seem inevitably to psychology of today (Simonton, 1992). -

The Third Epistle of John

The Third Epistle Of John A Study Guide With Introductory Comments, Summaries, And Review Questions Student Edition This material is from ExecutableOutlines.com, a web site containing sermon outlines and Bible studies by Mark A. Copeland. Visit the web site to browse or download additional material for church or personal use. The outlines were developed in the course of my ministry as a preacher of the gospel. Feel free to use them as they are, or adapt them to suit your own personal style. To God Be The Glory! Executable Outlines, Copyright © Mark A. Copeland, 2011 2 The Third Epistle Of John Table Of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter One 5 This study guide was designed for adult Bible classes, though it might be suitable for junior and senior high classes as well. Some have used it for personal devotions, and others in small study groups. In whatever way it can be used to the glory of God, I am grateful. • Points to ponder for each chapter are things I emphasize during the class. • Review questions are intended to reinforce key thoughts in each chapter. There is a “teacher’s edition” available with answers included. ExecutableOutlines.com 3 The Third Epistle Of John Introduction What was the early church like? We know a lot about its early leaders, such as apostles Paul and Peter; but what about the average Christians themselves? Were they more spiritual than Christians today? Did they experience the kind of problems seen so often in churches today? Several books of the New Testament reflect the life of the early church, and this is especially true of The Third Epistle of John. -

Hospitality Versus Patronage: an Investigation of Social Dynamics in the Third Epistle of John

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2007 Hospitality Versus Patronage: an Investigation of Social Dynamics in the Third Epistle of John Igor Lorencin Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lorencin, Igor, "Hospitality Versus Patronage: an Investigation of Social Dynamics in the Third Epistle of John" (2007). Dissertations. 87. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/87 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT HOSPITALITY VERSUS PATRONAGE: AN INVESTIGATION OF SOCIAL DYNAMICS IN THE THIRD EPISTLE OF JOHN by Igor Lorencin Adviser: Robert M. Johnston Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: HOSPITALITY VERSUS PATRONAGE: AN INVESTIGATION OF SOCIAL DYNAMICS IN THE THIRD EPISTLE OF JOHN Name of researcher: Igor Lorencin Name and degree of faculty adviser: Robert M. Johnston, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2007 Problem This investigation focuses on social dynamics in the third epistle of John. -

Ordines Militares Conference

ORDINES◆ MILITARES COLLOQUIA TORUNENSIA HISTORICA Yearbook for the Study of the Military Orders vol. XIX (2014) Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika Towarzystwo Naukowe w Toruniu Toruń 2014 Editorial Board Roman Czaja, Editor in Chief, Nicolaus Copernicus University Toruń Jürgen Sarnowsky, Editor in Chief, University of Hamburg Jochen Burgtorf, California State University Sylvain Gouguenheim, École Normale Supérieure Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Lyon Hubert Houben, Università del Salento Lecce Alan V. Murray, University of Leeds Krzysztof Kwiatkowski, Assistant Editor, Nicolaus Copernicus University Toruń Reviewers: Udo Arnold, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn (retired) Karl Borchardt, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, München Jochen Burgtorf, Department of History, California State University Wiesław Długokęcki, Institute of History, University of Gdańsk Marie-Luise Favreau-Lilie, Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut, Freie Universität Berlin Alan Forey, Durham University (retired) Mario Glauert, Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv in Potsdam Sylvain Gouguenheim, Ecole Normale Supérieure Lettres et Sciences Humaines de Lyon Dieter Heckmann, Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin-Dahlem Ilgvars Misāns, Faculty of History and Philosophy, University of Latvia, Riga Maria Starnawska, Institute of History, Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa Sławomir Zonenberg, Institute of History and International Relationships, Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz Janusz Tandecki, Institut of History and Archival Sciences, Nicolaus -

John Ashbery 125 Part Twelve the Voyages of John Matthias 133

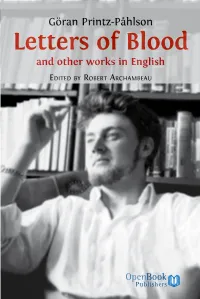

Göran Printz-Påhlson Letters of Blood and other works in English EDITED BY ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/86 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Edited by Robert Archambeau https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2011 Robert Archambeau; Foreword © 2011 Elinor Shaffer; ‘The Overall Wandering of Mirroring Mind’: Some Notes on Göran Printz-Påhlson © 2011 Lars-Håkan Svensson; Göran Printz-Påhlson’s original texts © 2011 Ulla Printz-Påhlson. Version 1.2. Minor edits made, May 2016. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Göran Printz-Påhlson, Robert Archambeau (ed.), Letters of Blood. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0017 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. openbookpublishers.com/product/86#copyright Further details about CC BY-NC-ND licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/ All the external links were active on 02/5/2016 unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume can be found at https://www. -

GRE Vocabulary

Table of Contents Introduction About Us What is Magoosh? Featured in Why Our Students Love Us How to Use Vocabulary Lists Timmy’s Vocabulary Lists Shirley’s Vocabulary Lists Timmy’s Triumph Takeway Making Words Stick: Memorizing GRE Vocabulary Come up with Clever (and Wacky) Associations Use It or Lose It Do Not Bite Off More Than You Can Chew Read to Be Surprised Takeaways Most Common GRE Words Top 10 GRE Words of 2012 Top 5 Basic GRE Words Common Words that Students Always Get Wrong Tricky “Easy” GRE Words with Multiple Meanings Commonly Confused Sets Interesting (and International) Word Origins Around the World French Words Eponyms Words with Strange Origins Themed Lists Vocab from Within People You Wouldn’t Want To Meet Religious Words Words from Political Scandals Money Matters: How Much Can You Spend? Money Matters: Can’t Spend it Fast Enough Money Matters: A Helping (or Thieving!) Hand Vocabulary from up on High Preposterous Prepositions Them’s Fighting Words gre.magoosh.com 1 Animal Mnemonics Webster’s Favorites “Occupy” Vocabulary Compound Words Halloween Vocabulary Talkative Words By the Letter A-Words C-Words Easily Confusable F-Words Vicious Pairs of V’s “X” words High-Difficulty Words Negation Words: Misleading Roots Difficult Words that the GRE Loves to Use Re- Doesn’t Always Mean Again GRE Vocabulary Books: Recommended Fiction and Non-Fiction The Best American Series The Classics Takeaway Vocabulary in Context: Articles from Magazines and Newspapers The Atlantic Monthly The New Yorker New York Times Book Review The New York Times Practice Questions Sentence Equivalence Text Completion Reading Comprehension GRE Vocabulary: Free Resources on the Internet gre.magoosh.com 2 Introduction This eBook is a compilation of the most popular Revised GRE vocabulary word list posts from the Magoosh GRE blog. -

Magooshgrevocabebook.Pdf

Updated 1/15/13 1 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 About Us ................................................................................................................... 4 What is Magoosh? ...................................................................................................... 4 Featured in ............................................................................................................. 4 Why Our Students Love Us ........................................................................................... 5 How to Use Vocabulary Lists ........................................................................................... 7 Timmy’s Vocabulary Lists ............................................................................................ 7 Shirley’s Vocabulary Lists ............................................................................................ 7 Timmy’s Triumph ...................................................................................................... 8 Takeway ................................................................................................................. 8 Making Words Stick: Memorizing GRE Vocabulary................................................................... 9 Come up with Clever (and Wacky) Associations .................................................................. 9 Use It or Lose It ....................................................................................................... -

The Apostolic Scriptures Practical Messianic Edition

THE APOSTOLIC SCRIPTURES PRACTICAL MESSIANIC EDITION FOR THE PRACTICAL MESSIANIC COMMENTARY SERIES by J.K. McKee A Survey of the Tanach for the Practical Messianic A Survey of the Apostolic Scriptures for the Practical Messianic The Apostolic Scriptures Practical Messianic Edition Acts 15 for the Practical Messianic James for the Practical Messianic Romans for the Practical Messianic 1 Corinthians for the Practical Messianic 2 Corinthians for the Practical Messianic Galatians for the Practical Messianic Ephesians for the Practical Messianic Philippians for the Practical Messianic Colossians and Philemon for the Practical Messianic 1&2 Thessalonians for the Practical Messianic The Pastoral Epistles for the Practical Messianic Hebrews for the Practical Messianic THE APOSTOLIC SCRIPTURES PRACTICAL MESSIANIC EDITION ADAPTED FROM THE 1901 AMERICAN STANDARD VERSION A SPECIALTY MESSIANIC EDITION OF THE NEW TESTAMENT MESSIANIC APOLOGETICS messianicapologetics.net THE APOSTOLIC SCRIPTURES PRACTICAL MESSIANIC EDITION 2015, 2018, 2021 Messianic Apologetics edited by J.K. McKee All rights reserved. With the exception of quotations for academic purposes, no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission of the publisher. Cover imagery: PapaBear/Istockphoto ISBN 978-1493502745 (paperback) ISBN 979-8738759369 (hardcover) ASIN B011WNE1JY (eBook) Published by Messianic Apologetics, a division of Outreach Israel Ministries P.O. Box 516 McKinney, Texas 75070 (407) 933-2002 www.outreachisrael.net www.messianicapologetics.net THE APOSTOLIC -

General Epistles First, Second & Third John

General Epistles First, Second & Third John Transcript Book By Fred R. Coulter 2017 Fred R. Coulter Christian Biblical Church of God P. O. Box 1442 Hollister, California 95024-1442 All rights reserved. Except for brief excerpts for review purposes, no part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without the written permission of the copyright owner. This includes electronic and mechanical photocopying or recording, as well as the use of information storage and retrieval systems. DOCUMENT of COMPLETION THIS ACKNOWLEDGES THAT, I HAVE SUCCESSFULLY COMPLETED 1st, 2nd & 3rd John Series of 13 sermons by Fred R. Coulter Signature Date Epistle of First John #1 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #2 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #3 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #4 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #5 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #6 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #7 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #8 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #9 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #10 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #10a Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #11 Date completed __________________ Epistle of First John #12 Date completed __________________ Contents Booklet PAGE Epistle of First John I --------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 -

Wenstrom Bible Ministries Pastor-Teacher Bill Wenstrom Tuesday January 31, 2017

Wenstrom Bible Ministries Pastor-Teacher Bill Wenstrom Tuesday January 31, 2017 www.wenstrom.org First John: Canonicity of Johannine Epistles Lesson # 2 The term “canon” or “canonicity” in Christianity refers to a collection of many books acknowledged or recognized by the early church as inspired by God. Canonicity is actually determined by God or in other words, a book is not inspired because men determined or decreed that it was canonical but rather it is canonical because God inspired it. It was not the Jewish people who determined what should be in their Old Testament and it was not the Christian community that determined which Christian literary works would be in the New Testament canon. Therefore, inspiration determines canonization. Canonicity is determined authoritatively by God and this authority is simply recognized by His people. The biblical canon is not, of course, primarily a collection or list of literary masterpieces, like the Alexandrian lists, but one of authoritative sacred texts. Their authority is derived not from their early date, nor from their role as records of revelation (important though these characteristics were), but from the fact that they were believed to be inspired by God and thus to share the nature of revelation themselves. This belief, expressed at various points in the OT, had become a settled conviction among Jews of the intertestamental period, and is everywhere taken for granted in the NT treatment of the OT. That NT writings share this scriptural and inspired character is first stated in 1 Timothy 5:18 and 2 Peter 3:16. Pagan religion also could speak of ‘holy scriptures’ and attribute them on occasion to a deity (see J. -

The Third Epistle of John

The Third Epistle Of John Sermon Outlines This material is from ExecutableOutlines.com, a web site containing sermon outlines and Bible studies by Mark A. Copeland. Visit the web site to browse or download additional material for church or personal use. The outlines were developed in the course of my ministry as a preacher of the gospel. Feel free to use them as they are, or adapt them to suit your own personal style. To God Be The Glory! Executable Outlines, Copyright © Mark A. Copeland, 2006 Mark A. Copeland The Third Epistle Of John Table Of Contents The Three Men Of Third John (1-14) 3 Spiritual And Material Prosperity (2-4) 7 Supporting Ministers Of The Gospel (5-8) 10 The Spirit Of Diotrephes (9-10) 13 Imitating The Good (11-12) 17 Sermons From Third John 2 Mark A. Copeland The Three Men Of Third John 3 John 1-13 INTRODUCTION 1. It is not unusual for people to wonder... a. What was the early church like? b. We know a lot about its early leaders, such as apostles Paul and Peter; but what about the average Christians themselves? c. Were they more spiritual than Christians today? Did they experience the kind of problems seen so often in churches today? 2. Several books of the New Testament reflect the life of the early church, and this is especially true of the Third Epistle of John... a. It is a private letter, between the apostle John and a Christian named Gaius b. It provides portraits of three different men, and in so doing gives us a glimpse of 1st century life in a local church 3.