PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of the Italian Motorway Network (1924-1974)

pavese.qxp 01/09/2006 12:45 PÆgina 96 Transportes, Servicios y Telecomunicaciones, número 10 [96] Resumen CLAUDIO PAVESE, born in 1944, Laurea magistralis in ste trabajo analiza cómo se ha implementado la red italiana Economic History, University of Ede autopistas en dos fases diferentes (1922-1935 y 1958- Milan (Italy). 1974), con características originales, y en cierto modo inno- Current possition: Professor of vadoras, a nivel europeo. En esos dos períodos, la precocidad de Economic History and la realización italiana debe atribuirse a razones de orden geográ- Technology and Enterprise fico, histórico y económico. La falta de adecuación de la red de History, Faculty of Political carreteras ordinarias (a causa de la orografía de gran parte del Sciences, Università degli Studi di territorio y de la escasez de inversiones previas) indujo a la clase Milano. política (convencida de que, en un país todavía atrasado, una red Current oficies: Scientific viaria eficiente constituiría un poderoso factor de moder- Committee: “Associazione ASSI nización) a tomar en consideración la presión ejercida por las di storia e studi sull’impresa” grandes empresas interesadas en el desarrollo de la automoción (Milan) and ISEC (Instituto per lo (fabricantes de coches, de neumáticos, productores de cemento studio della Storia contempo- y empresas petroleras). La ejecución y financiación se llevaron ranea) (Sesto S.G.). Editorial a cabo principalmente a través de los instrumentos de interven- Board: Annali di storia dell’im- ción en la economía de que el Estado italiano se había dotado a presa; Archivi e imprese. sí mismo a partir de la década de 1930 (IRI). -

A Challenge for the Meuse-Rhine Euregio

No. 42 - June/July 2008 The Meuse-Rhine Euregio wishes to improve its competitiveness while remaining close to its citizens Wim Weijnen ”Togetherness in diversity”, a challenge for the Director General of the Province of Euregio Limburg (Netherlands) The Meuse-Rhine Euregio (EMR), formed in 1976, represents one of the oldest partnerships in Europe. With its 3.9 million Meuse-Rhine Euregio (EMR) was one of inhabitants and shared by three countries the first Euregions formed in Europe. and five cultures, it is now and more than What do you make of these past thirty ever before looking to the future. years of activity? The Meuse-Rhine Euregio, with a surface area First of all I would like to point out the of 10,700km², consists of five partner regions: specificity of EMR in relation to other the south of the Province of Limburg Euroregions: it incorporates not only three (Netherlands), the Province of Limburg countries but also five different cultures. (Belgium), the Province of Liège (Belgium), the Maastricht in the Netherlands - Headquarters Cross-border cooperation is therefore more Regio Aachen (Germany) and the German- of the EMR Stichting delicate and the projects which have been speaking community of Belgium. implemented over these thirty years have The objective of the Euregio at its formation in been mostly of an irregular and temporary technology, training, qualification and labour 1976 was to re-establish the relations within nature, notably in the areas of culture and market” commission, a second “nature, its territory unified by Charlemagne, only to be tourism, although nowadays things are environment and transport” commission, a third somewhat randomly separated in the 19th tending to change. -

Maps -- by Region Or Country -- Eastern Hemisphere -- Europe

G5702 EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5702 Alps see G6035+ .B3 Baltic Sea .B4 Baltic Shield .C3 Carpathian Mountains .C6 Coasts/Continental shelf .G4 Genoa, Gulf of .G7 Great Alföld .P9 Pyrenees .R5 Rhine River .S3 Scheldt River .T5 Tisza River 1971 G5722 WESTERN EUROPE. REGIONS, NATURAL G5722 FEATURES, ETC. .A7 Ardennes .A9 Autoroute E10 .F5 Flanders .G3 Gaul .M3 Meuse River 1972 G5741.S BRITISH ISLES. HISTORY G5741.S .S1 General .S2 To 1066 .S3 Medieval period, 1066-1485 .S33 Norman period, 1066-1154 .S35 Plantagenets, 1154-1399 .S37 15th century .S4 Modern period, 1485- .S45 16th century: Tudors, 1485-1603 .S5 17th century: Stuarts, 1603-1714 .S53 Commonwealth and protectorate, 1660-1688 .S54 18th century .S55 19th century .S6 20th century .S65 World War I .S7 World War II 1973 G5742 BRITISH ISLES. GREAT BRITAIN. REGIONS, G5742 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .C6 Continental shelf .I6 Irish Sea .N3 National Cycle Network 1974 G5752 ENGLAND. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G5752 .A3 Aire River .A42 Akeman Street .A43 Alde River .A7 Arun River .A75 Ashby Canal .A77 Ashdown Forest .A83 Avon, River [Gloucestershire-Avon] .A85 Avon, River [Leicestershire-Gloucestershire] .A87 Axholme, Isle of .A9 Aylesbury, Vale of .B3 Barnstaple Bay .B35 Basingstoke Canal .B36 Bassenthwaite Lake .B38 Baugh Fell .B385 Beachy Head .B386 Belvoir, Vale of .B387 Bere, Forest of .B39 Berkeley, Vale of .B4 Berkshire Downs .B42 Beult, River .B43 Bignor Hill .B44 Birmingham and Fazeley Canal .B45 Black Country .B48 Black Hill .B49 Blackdown Hills .B493 Blackmoor [Moor] .B495 Blackmoor Vale .B5 Bleaklow Hill .B54 Blenheim Park .B6 Bodmin Moor .B64 Border Forest Park .B66 Bourne Valley .B68 Bowland, Forest of .B7 Breckland .B715 Bredon Hill .B717 Brendon Hills .B72 Bridgewater Canal .B723 Bridgwater Bay .B724 Bridlington Bay .B725 Bristol Channel .B73 Broads, The .B76 Brown Clee Hill .B8 Burnham Beeches .B84 Burntwick Island .C34 Cam, River .C37 Cannock Chase .C38 Canvey Island [Island] 1975 G5752 ENGLAND. -

Report on the State of the Alps. Alpine Signals – Special Edition 1. Transport

ALPINE CONVENTION Report on the State of the Alps Alpine Signals – Special edition 1 Transport and Mobility in the Alps Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention www.alpconv.org [email protected] Office: Herzog-Friedrich-Straße 15 A-6020 Innsbruck Austria Branche office: Drususallee 1 I-39100 Bozen Italy Imprint Editor: Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention Herzog-Friedrich-Straße 15 A-6020 Innsbruck Austria Responsible for the publication series: Dr. Igor Roblek, Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention Graphical design: Ingenhaeff-Beerenkamp, Absam (Austria) Ifuplan, Munich (Germany) Cover photo: Marco Onida © Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention, Innsbruck, 2007 (if not indicated different). ALPINE CONVENTION Report on the State of the Alps Alpine Signals – Special edition 1 Transport and Mobility in the Alps The present document has been established under the coordination of the Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention involving an “Integration Group” composed by experts from different Member Countries of the Alpine Convention. Based on discussions in this group, the different chapters have been drafted by different authors. The Working Group “RSA/SOIA” and the Working Group “Transport” have accompanied the drafting process. National delegations have provided extensive comments on previous drafts. The Permanent Secretariat thanks all persons involved for their intensive cooperation. The Integration Group was composed by: • Austria: Bernhard Schwarzl (UBA Wien), he was helped by several collaborators: -

Cuneo Caraglio Dronero Demonte Borgo San Dalmazzo Barcelonnette

Cima del Pelvo Punta Vergia Scalenghe La Grande Roche du Lauzon Monte Cialmetta San Bernardo Pointe du Sélé Saint-Antoine 1260 262 La Rouya Cervières 3264 2992 Punta Gardetta Malanaggio L’Olan Mont Gioberney 3556 274-578 1831 Pointe Guyard Villar-Saint-Pancrace 2335 2737 Monte Servin Rif. Vaccera a 3350 B 1468 in A B 2751C D n ria F G H I Monte Freidour L M Monte Craviale N O P m Q R 35646°12’E Cime du Vallon Ref. du6°18’E Pigeonnier 3461 6°24’E 6°30’E o n 6°48’ECima Dormillouse 6°54’E 7°00’E 7°06’E 7°12’E 7°18’E 7°24’E 7°30’Ee 7°36’E 7°42’E Pointe du Rascrouset La Blanche ç ço Turge de Peyron 1756 Gaido L Aiguille des Saffres an n 2571 Rif. Jumarre 787 Miradolo 376 3418 ri 2908 Buriasco 1 3135 3082 2954 B Bric Froid 301 Sommet Sud des Bans Puy Aillaud 2791 Lem Pic du Lauzon Tête d’Amont ina Ref. de l’Olan Ref. de Chalance 4 Cime de la Charvie Monte Terra Nera Prarostino Osasio 2344 2560 Chalet Ref. 3669 3302 Punta Cialancia Punta Rognosa Pinerolo 245 413 241 2949 du Globerney 2814 Rif. Alpino 738 San Luigi 2881 3100 ai Sap Virle Piemonte Piton de la Viaclose Vallouise 2855 1321 San Secondo Lem o Le villard ina SP 663 P l a S e 1200 Punta Merciantaria Cima Frappier Baudenasca nd D 904 di Pinerolo 3010 Ref. des Bans L’O d e é Le Petit Peygu Cercenasco l é e 2083 Pic Charbonnel 3003 Punta Cornour Rif. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Frejusvr

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Master in Computer Engineering Master Thesis FrejusVR On the Use of Virtual Reality for Studying Human Behaviors During Emergencies Supervised by Calandra Davide Prof. Fabrizio Lamberti Prof. Andrea Sanna Prof. Romano Borchiellini October 2017 FrejusVR On the Use of Virtual Reality for Studying Human Behaviors During Emergencies Calandra Davide Supervised by: Prof. Fabrizio Lamberti Prof. Andrea Sanna Prof. Romano Borchiellini Abstract Virtual Reality (VR), since its appearance, played a big part in the development of more and more effective training tools in comparison with the past. Training simulators could provide the inexperienced user a realistic, immersive and safe Vir- tual Environment (VE) designed to accurately reproduce a given scenario with the purposes of information, training and evaluation. This work aims at providing a beneficial VR tool with the purpose of the communicating to the general user the emergency procedures concerning a particular scenario, a fire developing from an heavy vehicle inside the Fr´ejus road tunnel. Taking advantage of the collaboration with the tunnel Authority and undergoing a tailored testing plan, the work also provides an in-depth data analysis with the purpose of assessing the developed platform. 3 Acknowledgements First of all, I want to thank a lot my supervisors, Prof. Lamberti Fabrizio, Prof. Andrea Sanna and Prof. Romano Borchiellini, for the constant support, guidance and availability they provided through the whole development of the work. Then, I wank to thank a lot SiTI, in the person of Sergio Olivero and his staff Mas- simo Migliorini, Alessandra Filieri, Valentina Dolci and Francesco Moretti, along with all the other people met over there, for the constant organizational, technolog- ical, technical and moral support provided during the months spent with them. -

Aberystwyth University Permafrost Conditions in the Mediterranean Region Since the Last Glaciation

Aberystwyth University Permafrost conditions in the Mediterranean region since the Last Glaciation Oliva, M.; Žebre, M.; Guglielmin, M.; Hughes, P. D.; Çiner, A.; Vieira, G.; Bodin, X.; Andrés, N.; Colucci, R. R.; García-Hernández, C.; Mora, C.; Nofre, J.; Palacios, D.; Pérez-Alberti, A.; Ribolini, A.; Ruiz-Fernández, J.; Sarkaya, M. A.; Serrano, E.; Urdea, P.; Valcárcel, M. Published in: Earth-Science Reviews DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.06.018 Publication date: 2018 Citation for published version (APA): Oliva, M., Žebre, M., Guglielmin, M., Hughes, P. D., Çiner, A., Vieira, G., Bodin, X., Andrés, N., Colucci, R. R., García-Hernández, C., Mora, C., Nofre, J., Palacios, D., Pérez-Alberti, A., Ribolini, A., Ruiz-Fernández, J., Sarkaya, M. A., Serrano, E., Urdea, P., ... Yldrm, C. (2018). Permafrost conditions in the Mediterranean region since the Last Glaciation. Earth-Science Reviews, 185, 397-436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.06.018 Document License CC BY-NC-ND General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

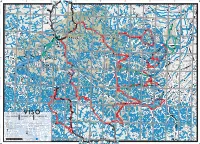

Pilot Profile

Project number: 639 Project acronym: trAILs Project title: Alpine Industrial Landscapes Transformation DELIVERABLE D.T1.3.3 Pilot profile WPT1 Map AILs: data collection, harmonization and transfer into Work package: webGIS Activity: Activity A.T1.3 Organization: LAMORO Development Agency – Project Partner 6 Deliverable date: November 2018 Version: 1 Dissemination level: Regional and Local stakeholders Dissemination target: Regional and Local This project is co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund through the Interreg Alpine Space programme CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 REGIONAL PP S AND LOCAL STAKEHOLDER NETWORK ................................................................................................ 3 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THE REGION............................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2.1 VALLE GESSO – GESSO VALLEY ....................................................................................................................... 9 1.2.2 VALLE VERMENAGNA.......................................................................................................................................... 9 2 REGIONAL PROFILE ............................................................................................................................ 10 2.1 NATURAL CONDITIONS AND LANDSCAPE ................................................................................................................. -

The Italian Occupation of Southeastern France in the Second World War, 1940–1943

Italiani Brava Gente? The Italian occupation of southeastern France in the Second World War, 1940-1943 by Emanuele Sica A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Emanuele Sica 2011 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Many academic works have focused on the German occupation of France in the Second World War, both from the perspective of the occupiers and the occupied. Only a few monographs however had dealt so far with the Italian military occupation of southeastern France between 1940 and 1943. My dissertation strives to fill this historiographical gap, by analyzing the Italian occupation policy established by both Italian civilian and military authorities. Compared to the German occupation policy, the Italian occupation was considerably more lenient, as no massacres were perpetrated and wanton violence was rare. In fact, the Italian occupation of France contrasts sharply with the occupation in the Balkans, where Italians resorted to brutal retaliation in response to guerilla activities. Indeed, softer measures in France stemmed from pragmatic reasons, as the Italian army had not the manpower to implement a draconian occupation, but also due to an humanitarian mindset, especially with regards to the Jewish population in southeastern France. This work endeavors to examine the occupation and its impact on southeastern France, especially at a grassroots level, with a particular emphasis on the relations between the Italian soldiers and the Italian immigrants in the area. -

Pag Chr Prova

2 12.00 % MAX GRADIENT 7.00 % GRADIENT AVERAGE m 1406 DIFFERENCE AL km 20.550 LENGTH Pian delRe(2020m) ARRIVAL (614m) Paesana DEPARTURE 4 TITUDE VALLE PO monviso - pian del re fauniera a n 2511 n o o i r A n 1 2365 . a i g 2301 S 2291 a u a p a t r o - n p e t n i i e o M t a a l i t i a t l . h e t l o n s a S S c e 2020 h l o r r s n i u o O i C o i l e a h i a s c f r C o 1761 F n E C n s e o e ' r 1661 r u s p i R O e e d s 1600 T a l r . p l 1526 l r e o f F e C i i l e e v o l o v s 1420 R i p i e d o C a l v i a B at uphillstretches,long andpanoramic wearrive tively respec- Massimiliano LelliandMarcoGiovannetti here twice, in1991and1992, ithasbeenwonby Stone”Valley. Girod’Italiahasbeen The inthePo Crissolo Oncino areunder We PIAN DEL RE MONVISO- is aseriesofhairpinbendsuntilthejunctionfor mean sealevel), theroadclimbseasily.Then there ter knownas to analtitudeof1715metresatPianMeltzè, difficult stretchoftheroutehastobetackledup other villagesofSerreandBorgo. Nowthe most Shrine;Chiaffredo’s thenitgoesthroughthe tion leadstothetowncentrewherethereisSan bends andalonguphillstretchbeforereaching withafewdemandinghairpin climbs upwards altitude of2020metres. 1318 i C o n d i n G B v a a o a i i 1130 i r s v B P P i Pian delRe 1105 e 1000 B a 890 P 862 822 788 . -

Cuneo M Ountain

HIKING TOURS FOR EVERYBODY CUNEO MOUNTAIN * Land of passion. Piemonte. PIEMONTE REGIONE CONTENTS 4 Welcome to the Alps of the Province of Cuneo 6 Map 8 Comunità Montana Valli Po, Bronda e Infernotto 44 Comunità Montana Valli Gesso e Vermenagna 9 Monte Bracco: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mountain 46 Via dei Teit (The Roofs Road) 10 Le vie d’Oustano (The Oustano Roads) 47 Via Romana (The Roman Road) 11 The Mèire - The Pastures 48 Tour of the Nineteenth Century Forts 12 La Via del Sale lungo la Valle Po (The“Salt Road”along the Po Valley) 52 Comunità Montana Bisalta 14 Comunità Montana Valle Varaita 53 From the Pianfei lake to the Carthusian Monastery of Pesio 16 The Old Mine Tour 54 Tour of Fontana Cappa 17 The Alevè, the Bagnour Lake and Refuge 55 “Via dei Morti” (The Dead Road) 18 The Losetta Circuit 19 The Blue Lake - Rocca Senghi 56 Parco Naturale Alta Valle Pesio e Tanaro (The Upper Pesio and Tanaro Valleys Natural Park) 20 Comunità Montana Valle Maira 58 In the Lower Valley Woodland 22 The Occitan Pathways 59 Il Vallone del Marguareis 23 The Ciciu del Villar Natural Reserve 60 Cima Marguareis (The Ligurian Alps Peak) 24 Elva: a Spas per Lou Viol 26 The Cyclamen Didactic Pathway 62 Comunità Montana Valli Monregalesi 64 At the Sources of the Ellero Stream 27 Comunità Montana Valle Grana 65 The Lakes of Brignola and Raschera 29 From the Colletto di Castelmagno Village to Colle della Margherita 66 Tour of the Community Ovens 30 From the Sanctuary “Santuario di San Magno” to Bassa di Narbona 31 From the Chiappi di Castelmagno hamlet to the Passo -

Loving It up the Ballon

Loving it up the Ballon Introduction Purely for our own amusement and reflection this travelogue revolves around a bunch of mates who enjoy motorcycling and in 2006 decided to do some touring in mainland Europe. Back then there were 5 of us and in the ensuing years riders have come and gone – 10 in all to date. With the exception of 2017 there has been a tour every year since and during that time we’ve ridden through 12 different countries over hundreds of mountain passes and clocked up 30,000 miles. 1 2006 Chamonix-Mont-Blanc For our inaugural motorcycle tour we decided to head for mainland Europe. The plan was simple, we would hop on a ferry and ride down to Chamonix-Mont-Blanc in the heart of the Western Alps and use Chalet Le Bois Rond as our base, from where we would ride some of the local Alpine roads and passes. Midway through the tour we’d ride out to Andermatt in Switzerland overnighting at Hotel Bergidyll before returning to Chamonix the following day. We figured it would take us a couple of days to get down there and a couple more days to get back and booked a stopover at Hotel du Lac de Madine in Heudicourt- sous-les-Cotes for the ride down, and at Le Clos du Montvinage in Etreaupont for the ride back. There was a twist though. It’s 800 miles from Bewdley to Chamonix of which the vast majority is very boring tyre squaring motorway. Phil had ridden it before and knew what he was in for so elected to drive and trailer his bike down a couple of days earlier.