Chinese Coin Guide - Ancient Knife and Spade Money SALES GALLERY GUIDE INDEX HOME CHINESE INDEX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Fear 2000 O Workers' [Ights O Tibetan Lmpressions Chilie Talks About His Recent Trip HIGHLIGHTS of the WEEK Back to Tibet (P

Vol. 25, No. 40 October 4, 1982 A CHINESE WEEKTY OF NEWS AND VIEWS Economic Iargels For the fear 2000 o Workers' [ights o Tibetan lmpressions chilie talks about his recent trip HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK back to Tibet (p. 22). New Central Committee Economic Targets by the China Was Top at WWVC Members Year 2000 The Chinese team was number An introduction to some of the General Secretary Hu Yao- one in the Ninth World Women's 271 middle-aged cadres who bang recently announced that Volleyball Championship in were recently elected to the Cen- China iirtends to quadruple its Pem, thus qualifying for the tral Committee of the Chinese gross annual value of industrial women's volleyball event in the Olympic Games years Communist Party (p. 5). and agricultural production by two from the year 2000. Historical, po- now (p. 28). Mrs. Thatcher in China litical and economic analyses support the conclusion that it is The first British Prime poasible to achieve this goal Minister to visit China, Mrs. (p. 16). Margaret Thatcher held talks with Chinese leaders on a numr .Workers' Congresses ber of questions, including bi- This report focuses on several lateral relations and Xianggang workers' congresses in Beijing (Hongkong) (p. 9). that ensure democratic manage- ment, through examining prod- Si no-J apanese Rerations uction plans, electing factory This September marked the leaders and supervising manage- 1Oth anniversary of the nor- ment (p. 20). malization of China-Japan rela- Today's Tibet tions. The rapid development of friendship and co-operation Oncs a Living Buddha, now between the two countries an associate professor of the during period reviewed Central Institute Nationali- An exciting moment during this is for the match between the Chi- (p. -

Airir •Orce < Flies in Ito Fla Rl I It^ Tk at 1< Learinj

' G a rme r commilission propip o s e s f e e ih i k e s f o r ' licenses, taQSt — IQ2 n : . ■ I I ChZlaasificd JJY o u r l ~ Z T teae sh**ia sm whMi. ln l ' r a v e l p C S I , p nr e p h a r r ieler ^ snrraculile, like n«w. lell- fU i RabbitsI a t fair: >ntaffwd. llB»p« 6. mmlna lI i ’at i l e r , w - atc:^^b a Sl i e i r t e r ------------ r — j,< jpwvim K i d s l o v e ’e m - Er r r — g larketplace C( 3 , < d i i v rl I iT^ f ■ I.Uglcv!^^'«^|^r*lnc. 8 4 thh year,; N o. 250 Twin Falla, Idadaho Thursday. SepilepJember 7. 1989 B jRepiK)rt ■ criticicizes H ^ o o i 1^8 H jail states By CRAIG LINCOlITOLN ' I Timcs-Ncws n'riteiriter H j^M | manages its jailini in a ‘horribly inadequate" mnnilanner, and its legal liability from the jail is “extreme," • ■ according to a repreport submitted to a judge Wednesday.ny. _ A litnnyi f ccomplnints from T1m*»N*w« pnotaWKE; 9 AisDunY prisoners, includiiluding threats by jail ' ‘ a n d n1 _rere p jjrt f^rom a ja il • he feels the Air forcc Iss ‘f‘taking away my backtkyard* w hile speakingg Ibefore Air Force officiiIcials-W ednesday night. B uhlattorneiney Bob W eaver says hc expert outline proiproblems-at a facility that once was "state-of-the"st art." It I —nowdirectlj-violiviolates the rights of ... -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

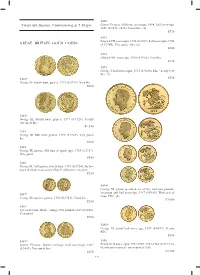

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2). -

Monetary Outlook: Internal Value of Money Stability Comparison in Usa

Volume 4 (1), 2021, 9-18 MONETARY OUTLOOK: INTERNAL VALUE OF MONEY STABILITY COMPARISON IN USA Budi Sasongko, STIE Jaya Negara Taman Siswa Malang, Indonesia Eny Lestari Widarni, STIE Jaya Negara Taman Siswa Malang, Indonesia Suryaning Bawono, STIE Jaya Negara Taman Siswa Malang, Indonesia ABSTRACT This paper aims to study the transformation of money in the United States using qualitative content analysis and predict the stability of the internal exchange rate of money by comparing the internal exchange rate of commodity money proxied by gold against crude oil internally. The exchange rate of fiat money proxied by the USD against crude oil and the internal exchange rate of synthetic money proxied by bitcoin against crude oil use the autoregressive threshold (TAR) method in the exchange period. In the great depression, fiat standards, subprime mortgage crisis, Europe experienced a debt crisis until 2017 (1960 - 2017). We compare the internal stability of money for each period in the aggregate using TAR to describe the overall fluctuation of internal exchange rate stability. So it can be seen that the behavior of data movements based on the crisis period experienced is the basis for predicting the stability of the internal exchange rate in the future. Keywords: monetary outlook, internal value of money, mixed-method 1. Introduction The money that is known today is fiat money in certain currencies in the world. Inflation that occurs throughout the world causes the exchange rate of money against goods to change from year to year. Inflation keeps prices high and never returns to the starting point of the long-run price change. -

Model-Insect Money of Ancient China, Amply

^m^mi^'U<'Ihii^^U''/:''rt- - 9i..WJi PiJk ^>^ »^aa SECT ONEY H. A. RAM SD EN, F.R.N.S. 1914 MODEL-INSECT MONEY OF ANCIENT CHINA. H. A. RAMSDEH F.R.N.S., President df the Yokohama Numismatic Society, District Secretary of the American Numismatic Association, etc. AtrtHOE OF Manuals of Far Eastern Numismatics, Corean Coin Charms and Amulets, Siamese Porcelain and other Tokens, Chinese Openwork Amulet Coins, etc. KDITOR OF "The Numismatic Monthly." " The Numismatic and Philatelic Journal of Japan," ,#==^ JUN KOBAYAOAWA Co. Numismatic &- Philatelic Printers &- Publishers, Yokohama, Japan. 1914. — 3 — Specialized Series. No. I, PREFATORY REMARKS. The greater part of the information contained in the following pages is mainly derived from an article by the author on the same subject and under the same heading, which originally appeared in the " Numismatic and Phila- telic Journal of Japan." The present monograph is, nevertheless, more than a mere excerpt from the above publication, since its scope has been considerably extended so as to include other matters having an indirect bearing on, if not actual connection with, the question under discussion. Readers acquainted with my previous efforts vi'ill consequently find herein embodied new material which it is hoped will add further interest to the topic indicated by the title. Although this contribution—the first of a uniform series which will be periodically published—is primarily intended for advanced scholars in this special line of study and research work, it has been at the same time written in a simple style with the endeavour of making it also as attractive as possible to the general reader. -

Power, Identity and Antiquarian Approaches in Modern Chinese Art

Power, identity and antiquarian approaches in modern Chinese art Chia-Ling Yang Within China, nationalistic sentiments notably inhibit objective analysis of Sino- Japanese and Sino-Western cultural exchanges during the end of the Qing dynasty and throughout the Republican period: the fact that China was occupied by external and internal powers, including foreign countries and Chinese warlords, ensured that China at this time was not governed or united by one political body. The contemporary concept of ‘China’ as ‘one nation’ has been subject to debate, and as such, it is also difficult to define what the term ‘Chinese painting’ means.1 The term, guohua 國畫 or maobihua 毛筆畫 (brush painting) has traditionally been translated as ‘Chinese national painting’. 2 While investigating the formation of the concept of guohua, one might question what guo 國 actually means in the context of guohua. It could refer to ‘Nationalist painting’ as in the Nationalist Party, Guomindang 國民黨, which was in power in early 20th century China. It could also be translated as ‘Republican painting’, named after minguo 民國 (Republic of China). These political sentiments had a direct impact on guoxue 國學 (National Learning) and guocui 國粹 (National Essence), textual evidence and antiquarian studies on the development of Chinese history and art history. With great concern over the direction that modern Chinese painting should take, many prolific artists and intellectuals sought inspiration from jinshixue 金石學 (metal and stone studies/epigraphy) as a way to revitalise the Chinese -

Title the CHINESE IDEAS of MONEY Author(S) Hozumi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Title THE CHINESE IDEAS OF MONEY Author(s) Hozumi, Fumio Citation Kyoto University Economic Review (1943), 18(1): 34-57 Issue Date 1943-01 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/125368 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University ··Kyoto University , Economic Review MEMOIRS OF THE QEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OF KYOTO VOLUME XVIII ". " 1943 ,....: .. , . .~. 0' PUDUSHED -nv TIlE DEPAR.'l'MENT OF. ECONOMICS IN . ,.J~:., " T~E IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OF KYOTO .~- . · THE CHINESE IDEAS OF MONEY By FUMIO HOZUMI Man cannot live by bread alone. This biblical iidage is true enough, but it is equally true that man cannot live without bread. In order to maintain his existence, man must consume material goods, -and in order ·that material.' ; goods be consumed, they should be produced. Human existence becomes possible· on the unified .process of the production and consumption of material goods. In the beginning man himself probably producea what he consumed himself. The following ancient Chinese poem· may be taken as an . evidence of this self-production for -man: A:t sunrise I begin my work, At sunset I take my repose, I dig a well to get my drink, / I plow my field to crop my rice ...... Why, then, should I e'er care About the Imperial power ?(1) Now, production is formed when labour is aded to the work of nature. But nature produces differently in different lands, nor is labour the same for different mell• Thus,. -

The Warring States and Monetizing Economies

The Warring States and Monetizing Economies An Analogical Research on the Causal Relationships between Geopolitics, Economics, and the Emergence of the Round Coinage of China Tiivistelmä ”The Warring States and Monetizing Economies: An Analogical Research on the Causal Relationships between Geopolitics, Economics, and the Emergence of the Round Coinage of China” on Helsingin yliopiston arkeologian oppiaineen pro gradu –tutkielma. Se on kirjoitettu englannin kielellä. Pro gradussa tutkitaan syitä sille, miksi Kiinassa otettiin Itäisen Zhou-dynastian aikana (770 - n. 256 eaa.) käyttöön pyöreät pronssikolikot toisenlaisten rahamuotojen rinnalle. Tuolloin Kiina koostui vielä useasta itsenäisestä valtiosta, jotka olivat jatkuvissa sodissa toisiaan vastaan. Pro gradussa osoitetaan pyöreiden kolikoiden pääfunktion olleen näiden valtioiden kansalaisten harjoittaman päivittäis- ja paikallistason kaupankäynnin helpottaminen, jolla on ollut suuri merkitys paikallisyhteisöjen vaurauden ja omavaraisuuden ylläpitämisessä. Tällä on puolestaan ollut merkittävä rooli kansalaisilta kerättyjen verovarojen määrän maksimoinnissa. Verovaroilla oli puolestaan hyvin merkittävä rooli valtioiden armeijoiden ylläpidossa, joiden olemassaoloon valtioiden selviytyminen nojautui. Pyöreiden kolikoiden suuri merkitys Itäisen Zhou-dynastian valtioiden paikallis- ja valtiotason ekonomiassa osoitetaan lähestymällä aihetta kolmen eri tutkimuskeinon avulla. Näistä ensimmäisenä käsiteltävä koskee aikakaudella käytettyjen pronssirahatyyppien fyysisiä eroja. Näiden perusteella -

American Numismatic Society Summer Graduate Seminar 2010

American Numismatic Society Summer Graduate Seminar 2010 Chinese Numismatic References: an Annotated Bibliography Robert W. Hoge and Frederic C. Withington Naturally, most research in Chinese numismatics has been performed in China and published in Chinese, and unfortunately, not much of it has been translated into English. However, enough material has either been translated or written in English to meet the needs of everyone except the most serious specialists. China changed radically in 1912 with the fall of the Empire. Since then, Chinese coins and paper money have been typically modern in style, with the issues reflecting the country’s chaotic recent history. The following references, and the Seminar lecture, are largely devoted to pre-1912 numismatics. Most information about modern Chinese numismatics can be obtained from commonly used general catalogs. Bruce, Colin R. II, sr. ed. 2007. Standard catalog of world coins: eighteenth century, 1701-1800, 4th ed. Iola, Wis.: Krause Publ. All types and issues covered. -- 2004. Standard catalog of world coins: 1801-1900, 4th ed. Iola, Wis.: KP Books -- [2009]. 2009 Standard catalog of world coins, 1901-2000, 36th ed. [Iola,Wis.]: Krause Publ. Burger, Werner. 1964. Manchu inscriptions on Chinese cash coins. Museum Notes 11, p. 313-318, pls. 50-55. New York: American Numismatic Society. -- 1976. Ch'ing cash until 1735. Taipei, Taiwan: Mei Ya Publ. The definitive study of these multitudinous issues. Coole, Arthur Braddon. 1936. Coins in China's history. Tientsin, Hopeh, China: Student work department of the Tientsin Hui Wen Academy. (4th reprint ed., Quarterman Publ., 1965). Brief and comprehensive, it contains inaccuracies corrected in Hartill and Peng. -

TIANANMEN: CHINA's STRUGGLE for DEMOCRACY ITS PRELUDE, DEVELOPMENT, AFTERMATH, and Impacf

OccAsioNAl PApERS/ REpRiNTS SERiES iN CoNTEMpoRARY AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 2 - 1990 (97) TIANANMEN: CHINA'S STRUGGLE FOR , DEMOCRACY , •• ITS PRELUDE, DEVELOPMENT, AFTERMATH, AND IMPACT Edited by Winston L. Y. Yang and Marsha L. Wagner Scltool of LAw UNivERsiTy of 0 MARylANd. c ' 0 Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Chih-Yu Wu Managing Editor: Chih-Yu Wu Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies, Korea University, Republic of Korea All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $18.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and $24.00 for Canada or overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS. Price for single copy of this issue: US $8.00. -

Economic and Trade Relations with NOTES from the EDITORS 4 Leaders of These South Pacific Countries

Vol. 28, No. 14 April 8, 1985 JING ^^-^^^ A CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS Deng Xiaoping on China's Second Revolution Research System Reforms Outlined North China's Largest Forestry Centre A view of the Saihanbo Forestry Centre. Farm workers water saplings. Covered with both dense forests and meadows, Saihanba is ideal for grazing livestock. Saihanba, an old Qing Dynasty hunting ground in Weichang County, Hebe! Province, has been turned into the largest forestry centre in north China. SPOTLIQHT HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK Vol. 28, No. 14 April 8, 1985 Hu Yaobang to Visit South Pacific In his upcoming visit to Australia, New Zealand, Western CONTENTS Samoa, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea, Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang will discuss economic and trade relations with NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 leaders of these South Pacific countries. The trip is aimed at Hu's South Pacific Trip Holds deepening understanding, promoting friendship and seeking Promise extensive co-operation and lasting peace in the area (p. 4). LETTERS 5 EVENTS & TRENDS 6-10 Reform Is 'Second Revolution' Deng: Reform Is 'Second Revolu• Chairman of the Central Advisory Commission Deng Xiao• tion' ping recently termed the nation's ongoing economic reform a Sessions Discuss Congress Reports Ministers Chart Growth Plan "second revolution." "China is determined to carry through China Sets Free Its Rural Economy its current reforms and is firm on its internal and external Support Pledged for Sierra Leone open policies," said Deng (p. 6). Production of Energy Increases INTERNATIONAL 11-14 Zhao On Reform of Scientific System South Africa: World Condemns Massacres China today urgently needs to reform its science manage• Bangladesh: Policies Speed Eco• nomic Growth ment system.