Ancient Chinese Cash Notes - the World’S First Paper Money

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download to View

The Mao Era in Objects Money (钱) Helen Wang, The British Museum & Felix Boecking, University of Edinburgh Summary In the early twentieth century, when the Communists gained territory, they set up revolutionary base areas (also known as soviets), and issued new coins and notes, using whatever expertise, supplies and technology were available. Like coins and banknotes all over the world, these played an important role in economic and financial life, and were also instrumental in conveying images of the new political authority. Since 1949, all regular banknotes in the People’s Republic of China have been issued by the People’s Bank of China, and the designs of the notes reflect the concerns of the Communist Party of China. Renminbi – the People’s Money The money of the Mao era was the renminbi. This is still the name of the PRC's currency today - the ‘people’s money’, issued by the People’s Bank of China (renmin yinhang 人民银 行). The ‘people’ (renmin 人民) refers to all the people of China. There are 55 different ethnic groups: the Han (Hanzu 汉族) being the majority, and the 54 others known as ethnic minorities (shaoshu minzu 少数民族). While the term renminbi (人民币) deliberately establishes a contrast with the currency of the preceding Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek, the term yuan (元) for the largest unit of the renminbi (which is divided into yuan, jiao 角, and fen 分) was retained from earlier currencies. Colloquially, the yuan is also known as kuai (块), literally ‘lump’ (of silver), which establishes a continuity with the silver-based currencies which China used formally until 1935 and informally until 1949. -

Chinese Underground Banking and 'Daigou'

Chinese Underground Banking and ‘Daigou’ October 2019 NAC/NECC v1.0 Purpose This document has been compiled by the National Crime Agency’s National Assessment Centre from the latest information available to the NCA regarding the abuse of Chinese Underground Banking and ‘Daigou’ for money laundering purposes. It has been produced to provide supporting information for the application by financial investigators from any force or agency for Account Freezing Orders and other orders and warrants under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. It can also be used for any other related purpose. This document is not protectively marked. Executive Summary • The transfer of funds for personal purposes out of China by Chinese citizens is tightly regulated by the Chinese government, and in all but exceptional circumstances is limited to the equivalent of USD 50,000 per year. All such transactions, without exception, are required to be carried out through a foreign exchange account opened with a Chinese bank for the purpose. The regulations nevertheless provide an accessible, legitimate and auditable mechanism for Chinese citizens to transfer funds overseas. • Chinese citizens who, for their own reasons, choose not to use the legitimate route stipulated by the Chinese government for such transactions, frequently use a form of Informal Value Transfer System (IVTS) known as ‘Underground Banking’ to carry them out instead. Evidence suggests that this practice is widespread amongst the Chinese diaspora in the UK. • Evidence from successful money laundering prosecutions in the UK has shown that Chinese Underground Banking is abused for the purposes of laundering money derived from criminal offences, by utilising cash generated from crime in the UK to settle separate and unconnected inward Underground Banking remittances to Chinese citizens in the UK. -

Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide

08 Investment.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 14/9/16 12:21 pm Page 81 Week in China China’s Tycoons Investment Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide Oceanwide Holdings, its Shenzhen-listed property unit, had a total asset value of Rmb118 billion in 2015. Hurun’s China Rich List He is the key ranked Lu as China’s 8th richest man in 2015 investor behind with a net worth of Rmb83 billlion. Minsheng Bank and Legend Guanxi Holdings A long-term ally of Liu Chuanzhi, who is known as the ‘godfather of Chinese entrepreneurs’, Oceanwide acquired a 29% stake in Legend Holdings (the parent firm of Lenovo) in 2009 from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences for Rmb2.7 billion. The transaction was symbolic as it marked the dismantling of Legend’s SOE status. Lu and Liu also collaborated to establish the exclusive Taishan Club in 1993, an unofficial association of entrepreneurs named after the most famous mountain in Shandong. Born in Shandong province in 1951, Lu In fact, according to NetEase Finance, it was graduated from the elite Shanghai university during the Taishan Club’s inaugural meeting – Fudan. His first job was as a technician with hosted by Lu in Shandong – that the idea of the Shandong Weifang Diesel Engine Factory. setting up a non-SOE bank was hatched and the proposal was thereafter sent to Zhu Getting started Rongji. The result was the establishment of Lu left the state sector to become an China Minsheng Bank in 1996. entrepreneur and set up China Oceanwide. Initially it focused on education and training, Minsheng takeover? but when the government initiated housing Oceanwide was one of the 59 private sector reform in 1988, Lu moved into real estate. -

The Digital Yuan and China's Potential Financial Revolution

JULY 2020 The digital Yuan and China’s potential financial revolution: A primer on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) BY STEWART PATERSON RESEARCH FELLOW, HINRICH FOUNDATION Contents FOREWORD 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WHAT IS IT AND WHAT COULD IT BECOME? 5 THE EFFICACY AND SCOPE OF STABILIZATION POLICY 7 CHINA’S FISCAL SYSTEM AND TAXATION 9 CHINA AND CREDIT AND THE BANKING SYSTEM 11 SEIGNIORAGE 12 INTERNATIONAL AND TRADE RAMIFICATIONS 13 CONCLUSIONS 16 RESEARCHER BIO: STEWART PATERSON 17 THE DIGITAL YUAN AND CHINA’S POTENTIAL FINANCIAL REVOLUTION Copyright © Hinrich Foundation. All Rights Reserved. 2 Foreword China is leading the way among major economies in trialing a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). Given China’s technological ability and the speed of adoption of new payment methods by Chinese consumers, we should not be surprised if the CBDC takes off in a major way, displacing physical cash in the economy over the next few years. The power that this gives to the state is enormous, both in terms of law enforcement, and potentially, in improving economic management through avenues such as surveillance of the shadow banking system, fiscal tax raising power, and more efficient pass through of monetary policy. A CBDC has the potential to transform the efficacy of state involvement in economic management and widens the scope of potential state economic action. This paper explains how a CBDC could operate domestically; specifically, the impact it could have on the Chinese economy and society. It also looks at the possible international implications for trade and geopolitics. THE DIGITAL YUAN AND CHINA’S POTENTIAL FINANCIAL REVOLUTION Copyright © Hinrich Foundation. -

For the Fear 2000 O Workers' [Ights O Tibetan Lmpressions Chilie Talks About His Recent Trip HIGHLIGHTS of the WEEK Back to Tibet (P

Vol. 25, No. 40 October 4, 1982 A CHINESE WEEKTY OF NEWS AND VIEWS Economic Iargels For the fear 2000 o Workers' [ights o Tibetan lmpressions chilie talks about his recent trip HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK back to Tibet (p. 22). New Central Committee Economic Targets by the China Was Top at WWVC Members Year 2000 The Chinese team was number An introduction to some of the General Secretary Hu Yao- one in the Ninth World Women's 271 middle-aged cadres who bang recently announced that Volleyball Championship in were recently elected to the Cen- China iirtends to quadruple its Pem, thus qualifying for the tral Committee of the Chinese gross annual value of industrial women's volleyball event in the Olympic Games years Communist Party (p. 5). and agricultural production by two from the year 2000. Historical, po- now (p. 28). Mrs. Thatcher in China litical and economic analyses support the conclusion that it is The first British Prime poasible to achieve this goal Minister to visit China, Mrs. (p. 16). Margaret Thatcher held talks with Chinese leaders on a numr .Workers' Congresses ber of questions, including bi- This report focuses on several lateral relations and Xianggang workers' congresses in Beijing (Hongkong) (p. 9). that ensure democratic manage- ment, through examining prod- Si no-J apanese Rerations uction plans, electing factory This September marked the leaders and supervising manage- 1Oth anniversary of the nor- ment (p. 20). malization of China-Japan rela- Today's Tibet tions. The rapid development of friendship and co-operation Oncs a Living Buddha, now between the two countries an associate professor of the during period reviewed Central Institute Nationali- An exciting moment during this is for the match between the Chi- (p. -

Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham

Victorianizing Guangxu: Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham Scott Relyea, Appalachian State University Abstract In the late Qing and early Republican eras, eastern Tibet (Kham) was a borderland on the cusp of political and economic change. Straddling Sichuan Province and central Tibet, it was coveted by both Chengdu and Lhasa. Informed by an absolutist conception of territorial sovereignty, Sichuan officials sought to exert exclusive authority in Kham by severing its inhabitants from regional and local influence. The resulting efforts to arrest the flow of rupees from British India and the flow of cultural identity entwined with Buddhism from Lhasa were grounded in two misperceptions: that Khampa opposition to Chinese rule was external, fostered solely by local monasteries as conduits of Lhasa’s spiritual authority, and that Sichuan could arrest such influence, the absence of which would legitimize both exclusive authority in Kham and regional assertions of sovereignty. The intersection of these misperceptions with the significance of Buddhism in Khampa identity determined the success of Sichuan’s policies and the focus of this article, the minting and circulation of the first and only Qing coin emblazoned with an image of the emperor. It was a flawed axiom of state and nation builders throughout the world that severing local cultural or spiritual influence was possible—or even necessary—to effect a borderland’s incorporation. Keywords: Sichuan, southwest China, Tibet, currency, Indian rupee, territorial sovereignty, Qing borderlands On December 24, 1904, after an arduous fourteen-week journey along the southern road linking Chengdu with Lhasa, recently appointed assistant amban (Imperial Resident) to Tibet Fengquan reached Batang, a lush green valley at the western edge of Sichuan on the province’s border with central Tibet. -

Ships Journals and Logs in Special Collections

This guide is an introduction to UNSW Special Collections unique collection of historic ships logs and naval journals, covering the period 1786-1905. Highlights include several midshipmens’ journals containing exquisite hand coloured engineering drawings, maps and vignettes; the adventurous tales of Thomas Moody who sailed along the Chinese coast in the late 1870s; and the official log of the HMS Pegasus, captained by the ‘sailor king’, Prince William Henry (later William IV), including a sighting of the young Captain Horatio Nelson in the West Indies, 1786-1788. It is a selective list of resources to get you started – you can search for other manuscripts using our Finding Aid Index and for rare books in the Search Gateway (refine your search results by Collection > Special Collections to identify rare books). If you would like to view Special Collections material or have any questions, please submit your enquiry via the Contact Us online enquiry form and we will be happy to help you. Please refer to the Special Collections website for further information. Ships journals and logs in Special Collections The following ships journals and logs in are held in Special Collections – for further information see also the detailed entries following this summary table: MANUSCRIPT NUMBER/TITLE DESCRIPTION PLACE MSS 369 Thomas Barrington Moody Bound manuscript journal written by Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, the Moody aboard HMS Egeria, 1878- China coast including Shanghai, 1881 Borneo, Siam and Malaya MSS 144 John L. Allen Private journal kept by Allen on a China and Japan voyage in HMS Ocean, 1869-1871, together with his notes on China MSS 222 G.K. -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

ISQ Symposium Moller

Balancing in the Balance An INTERNATIONAL STUDIES QUARTERLY ONLINE symposium Patrick Thaddeus Jackson William C. Wohlforth Deborah Boucoyannis Stuart J. Kaufman Benjamin de Carvalho Victoria Hui Jørgen Møller DeRaismes Combes, Managing Editor Published Online, 4July 2017 v1.0 Introduction ____________________________________________________1 Patrick Thaddeus Jackson Comment on Møller ______________________________________________2 William C. Wohlforth State Capacity and Collective Organization: The Sinews of European Balances _______4 Deborah Boucoyannis Hegemony and Balance: It’s Not Just Initial Conditions ______________________7 Stuart J. Kaufman Overpoising the Balance of Power? ____________________________________9 Benjamin de Carvalho Moller confirms “War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe” _ 12 Victoria Hui Reply to critics _________________________________________________15 Jørgen Møller References ____________________________________________________18 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License INTRODUCTION Patrick Thaddeus Jackson American University The balance of power has been a concern long before the field of academic international studies ever existed. Rulers, historians, politicians, and philosophers have all been concerned with the notion: what does it mean to have a balance of power? Are such balances stable? Can they only exist between independent polities, or within polities as well? Are balances the product of deliberate policies or institutional design, or are they the unintended consequences of other actions? Is a balance even desirable? Centuries of pondering such questions preceded the inauguration of international studies as a distinct academic realm in the early 20th century, making this a central concern not only for those in the modern academy, but for much of the entire rich history of reflections on politics. After so much ink has been spilled one might think that there is nothing more to say — nothing new, at any rate. -

About Beijing

BEIJING Beijing, the capital of China, lies just south of the rim of the Central Asian Steppes and is separated from the Gobi Desert by a green chain of mountains, over which The Great Wall runs. Modern Beijing lies on the site of countless human settlements that date back half a million years. Homo erectus Pekinensis, better known as Peking man was discovered just outside the city in 1929. It is China's second largest city in terms of population and the largest in administrative territory. The name Beijing - or Northern Capital - is a modern term by Chinese standards. It first became a capital in the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), but it experienced its first phase of grandiose city planning in the Yuan Dynasty under the rule of the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, who made the city his winter capital in the late 13th century. Little of it remains in today's Beijing. Most of what the visitor sees today dates from either the Ming or later Qing dynasties. Huge concrete tower blocks have mushroomed and construction sites are everywhere. Bicycles are still the main mode of transportation but taxis, cars, and buses jam the city streets. PASSPORT/VISA CONDITIONS All visitors to Beijing and the People's Republic of China are required to have a valid passport (one that does not expire for at least 6 months after your arrival date in China). A special tourist or business visa is also required. CUSTOMS Travelers are allowed to bring into China one bottle of alcoholic beverages and two cartons of cigarettes. -

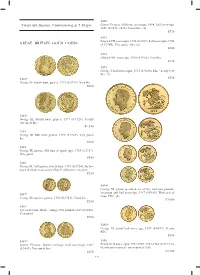

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2). -

Admiralty Dock 166 Agricultural Experimentation Site Nongshi

Index Admiralty Dock 166 Bishu shanzhuang 避暑山莊 88 Agricultural Experimentation Site nongshi bochuan剝船 125, 126 shiyan suo 農事實驗所 97 Bodde, Derk 295, 299 All-Hankou Guild Alliance Ge huiguan Bodolec, Caroline 28 各會館公所聯合會 gongsuo lianhe hui 327 bondservants 79, 82, 229, 264 Amelung, Iwo 88, 89 booi 264 American Banknote Company 237, 238 bound labour 60, 349 American Presbyterian Mission Press 253 Boxer Rebellion 143, 315, 356 Amoy. See Xiamen Bradstock, Timothy 327, 330, 331 潮州庵埠廠 Anfu, Chaozhou prefecture 188 brass utensils 95 Anhui 79, 120, 124, 132, 138, 139, 141, 172, 196, Bray, Francesca 25, 28, 317 249, 325, 342 bricklayers zhuanjiang 磚匠 91 安慶 Anqing 138 brickmakers 113 apprentices 99, 101, 102, 329, 333, 336, 337, 346 British Columbia 174 Arsenal 137, 146 brocade weavers 334 Arsenal wages 197, 199 Brokaw, Cynthia 28, 247, 248, 250, 251, 252, 255, artisan households 52 270, 274 artisan registration 94, 95 Brook, Timothy 62 匠体 artisan style jiangti 231 Bureau for Crafts gongyi ju 工藝局 97 Attiret, Denis 254, 269 Bureau for Weights and Measures quanheng Audemard 159, 169 duliang ju 權衡度量局 97 Auditing Office jieshen ku 節慎庫 75 Bureau of Construction yingshan qingli si 營繕 清吏司 74, 77, 106, 111, 335 baitang’a 栢唐阿 263 Bureau of Forestry and Weights yuheng qingli bang 幫 323, 331, 338, 342, 343 si 虞衡清吏司 74, 77 banner 263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 278 Bureau of Irrigation and Transportation dushui baofang 報房 234 qingli si 都水清吏司 75, 77 baogongzhi 包工制 196 Burger, Werner 28, 77 baogong 包工 112 Burgess, John S. 29, 326, 330, 336, 338 Baoquan ju 寳泉局 78, 107