ISQ Symposium Moller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ships Journals and Logs in Special Collections

This guide is an introduction to UNSW Special Collections unique collection of historic ships logs and naval journals, covering the period 1786-1905. Highlights include several midshipmens’ journals containing exquisite hand coloured engineering drawings, maps and vignettes; the adventurous tales of Thomas Moody who sailed along the Chinese coast in the late 1870s; and the official log of the HMS Pegasus, captained by the ‘sailor king’, Prince William Henry (later William IV), including a sighting of the young Captain Horatio Nelson in the West Indies, 1786-1788. It is a selective list of resources to get you started – you can search for other manuscripts using our Finding Aid Index and for rare books in the Search Gateway (refine your search results by Collection > Special Collections to identify rare books). If you would like to view Special Collections material or have any questions, please submit your enquiry via the Contact Us online enquiry form and we will be happy to help you. Please refer to the Special Collections website for further information. Ships journals and logs in Special Collections The following ships journals and logs in are held in Special Collections – for further information see also the detailed entries following this summary table: MANUSCRIPT NUMBER/TITLE DESCRIPTION PLACE MSS 369 Thomas Barrington Moody Bound manuscript journal written by Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, the Moody aboard HMS Egeria, 1878- China coast including Shanghai, 1881 Borneo, Siam and Malaya MSS 144 John L. Allen Private journal kept by Allen on a China and Japan voyage in HMS Ocean, 1869-1871, together with his notes on China MSS 222 G.K. -

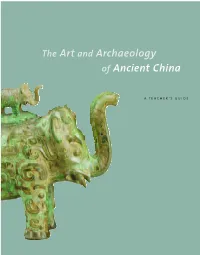

T H E a Rt a N D a Rc H a E O L O Gy O F a N C I E Nt C H I

china cover_correct2pgs 7/23/04 2:15 PM Page 1 T h e A r t a n d A rc h a e o l o g y o f A n c i e nt C h i n a A T E A C H E R ’ S G U I D E The Art and Archaeology of Ancient China A T E A C H ER’S GUI DE PROJECT DIRECTOR Carson Herrington WRITER Elizabeth Benskin PROJECT ASSISTANT Kristina Giasi EDITOR Gail Spilsbury DESIGNER Kimberly Glyder ILLUSTRATOR Ranjani Venkatesh CALLIGRAPHER John Wang TEACHER CONSULTANTS Toni Conklin, Bancroft Elementary School, Washington, D.C. Ann R. Erickson, Art Resource Teacher and Curriculum Developer, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia Krista Forsgren, Director, Windows on Asia, Atlanta, Georgia Christina Hanawalt, Art Teacher, Westfield High School, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia The maps on pages 4, 7, 10, 12, 16, and 18 are courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The map on page 106 is courtesy of Maps.com. Special thanks go to Jan Stuart and Joseph Chang, associate curators of Chinese art at the Freer and Sackler galleries, and to Paul Jett, the museum’s head of Conservation and Scientific Research, for their advice and assistance. Thanks also go to Michael Wilpers, Performing Arts Programmer, and to Christine Lee and Larry Hyman for their suggestions and contributions. This publication was made possible by a grant from the Freeman Foundation. The CD-ROM included with this publication was created in collaboration with Fairfax County Public Schools. It was made possible, in part, with in- kind support from Kaidan Inc. -

Linguistic Composition and Characteristics of Chinese Given Names DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8

Onoma 51 Journal of the International Council of Onomastic Sciences ISSN: 0078-463X; e-ISSN: 1783-1644 Journal homepage: https://onomajournal.org/ Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 Irena Kałużyńska Sinology Department Faculty of Oriental Studies University of Warsaw e-mail: [email protected] To cite this article: Kałużyńska, Irena. 2016. Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names. Onoma 51, 161–186. DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 © Onoma and the author. Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names Abstract: The aim of this paper is to discuss various linguistic and cultural aspect of personal naming in China. In Chinese civilization, personal names, especially given names, were considered crucial for a person’s fate and achievements. The more important the position of a person, the more various categories of names the person received. Chinese naming practices do not restrict the inventory of possible given names, i.e. given names are formed individually, mainly as a result of a process of onymisation, and given names are predominantly semantically transparent. Therefore, given names seem to be well suited for a study of stereotyped cultural expectations present in Chinese society. The paper deals with numerous subdivisions within the superordinate category of personal name, as the subclasses of surname and given name. It presents various subcategories of names that have been used throughout Chinese history, their linguistic characteristics, their period of origin, and their cultural or social functions. -

Who Began the Wars Between the Jin and Song Empires? (Based on Materials Used in Jurchen Studies in Russia)

Who began the wars between the Jin and Song Empires? (based on materials used in Jurchen studies in Russia) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Kim, Alexander A. 2013. Who began the wars between the Jin and Song Empires? (based on materials used in Jurchen studies in Russia). Annales d’Université Valahia Targoviste, Section d’Archéologie et d’Histoire, Tome XV, Numéro 2, p. 59-66. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33088188 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Annales d’Université Valahia Targoviste, Section d’Archéologie et d’Histoire, Tome XV, Numéro 2, 2013, p. 59-66 ISSN : 1584-1855 Who began the wars between the Jin and Song Empires? (based on materials used in Jurchen studies in Russia) Alexander Kim* *Department of Historical education, School of education, Far Eastern Federal University, 692500, Russia, t, Ussuriysk, Timiryazeva st. 33 -305, email: [email protected] Abstract: Who began the wars between the Jin and Song Empires? (based on materials used in Jurchen studies in Russia) . The Jurchen (on Chinese reading – Ruchen, 女眞 / 女真 , Russian - чжурчжэни , Korean – 여진 / 녀진 ) tribes inhabited what is now the south and central part of Russian Far East, North Korea and North and Central China in the eleventh to sixteenth centuries. -

十六shí Liù Sixteen / 16 二八èr Bā 16 / Sixteen 和hé Old Variant of 和/ [He2

十六 shí liù sixteen / 16 二八 èr bā 16 / sixteen 和 hé old variant of 和 / [he2] / harmonious 子 zǐ son / child / seed / egg / small thing / 1st earthly branch: 11 p.m.-1 a.m., midnight, 11th solar month (7th December to 5th January), year of the Rat / Viscount, fourth of five orders of nobility 亓 / 等 / 爵 / 位 / [wu3 deng3 jue2 wei4] 动 dòng to use / to act / to move / to change / abbr. for 動 / 詞 / |动 / 词 / [dong4 ci2], verb 公 gōng public / collectively owned / common / international (e.g. high seas, metric system, calendar) / make public / fair / just / Duke, highest of five orders of nobility 亓 / 等 / 爵 / 位 / [wu3 deng3 jue2 wei4] / honorable (gentlemen) / father-in 两 liǎng two / both / some / a few / tael, unit of weight equal to 50 grams (modern) or 1&frasl / 16 of a catty 斤 / [jin1] (old) 化 huà to make into / to change into / -ization / to ... -ize / to transform / abbr. for 化 / 學 / |化 / 学 / [hua4 xue2] 位 wèi position / location / place / seat / classifier for people (honorific) / classifier for binary bits (e.g. 十 / 六 / 位 / 16-bit or 2 bytes) 乎 hū (classical particle similar to 於 / |于 / [yu2]) in / at / from / because / than / (classical final particle similar to 嗎 / |吗 / [ma5], 吧 / [ba5], 呢 / [ne5], expressing question, doubt or astonishment) 男 nán male / Baron, lowest of five orders of nobility 亓 / 等 / 爵 / 位 / [wu3 deng3 jue2 wei4] / CL:個 / |个 / [ge4] 弟 tì variant of 悌 / [ti4] 伯 bó father's elder brother / senior / paternal elder uncle / eldest of brothers / respectful form of address / Count, third of five orders of nobility 亓 / 等 / 爵 / 位 / [wu3 deng3 jue2 wei4] 呼 hū variant of 呼 / [hu1] / to shout / to call out 郑 Zhèng Zheng state during the Warring States period / surname Zheng / abbr. -

China: Promise Or Threat?

<UN> China: Promise or Threat? <UN> Studies in Critical Social Sciences Series Editor David Fasenfest (Wayne State University) Editorial Board Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Duke University) Chris Chase-Dunn (University of California-Riverside) William Carroll (University of Victoria) Raewyn Connell (University of Sydney) Kimberlé W. Crenshaw (University of California, la, and Columbia University) Heidi Gottfried (Wayne State University) Karin Gottschall (University of Bremen) Mary Romero (Arizona State University) Alfredo Saad Filho (University of London) Chizuko Ueno (University of Tokyo) Sylvia Walby (Lancaster University) Volume 96 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/scss <UN> China: Promise or Threat? A Comparison of Cultures By Horst J. Helle LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the cc-by-nc License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover illustration: Terracotta Army. Photographer: Maros M r a z. Source: Wikimedia Commons. (https://goo.gl/WzcOIQ); (cc by-sa 3.0). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Helle, Horst Jürgen, author. Title: China : promise or threat? : a comparison of cultures / by Horst J. Helle. Description: Brill : Boston, [2016] | Series: Studies in critical social sciences ; volume 96 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016034846 (print) | lccn 2016047881 (ebook) | isbn 9789004298200 (hardback : alk. paper) | isbn 9789004330603 (e-book) Subjects: lcsh: China--Social conditions. -

Principales, /Lustra Dos, Intellectuals and the Original Concept of a Filipino National Community*

PRINCIPALES, /LUSTRA DOS, INTELLECTUALS AND THE ORIGINAL CONCEPT OF A FILIPINO NATIONAL COMMUNITY* Cesar Adib Majul Introduction: The concept of a Filipino national community was initially ver balized in the 1880's by the ilustrados, the educated elite which emerged from the principalia class in native society after the educa tional reforms of 1863. This concept was a function of native response to colonial and ecclesiastical domination as well as the result of an interaction between the different social classes in the colonial so ciety. The Philippine Revolution of 1896 and 1898 aimed, among other things, to concretize the concept. This was unlike the earlier twenty five or more major uprisings in the colony which were mainly based on personal, regional or sectarian motives. This paper aims to present a conceptual framework to under stand better how the concept of a Filipino national community was the inevitable consequence of certain historical events. It attempts to elicit further the significance of such events by relating them to each other. It will also indicate certain continuities in Philippine history, a hitherto neglected aspect, while belying an oft-repeated statement that the history of the Philippines during Spanish rule was mainly a history of the colonials. I. Spanish Conquest and Consolidation When the Spaniards came to the Philippines in 1565, they had the following major aims: the conversion of the natives to Christianity and the extension of the political domains and material interests of the Spanish monarch. What they found in Luzon, the Visayas and parts of Mindanao was a constellation of widely scattered settlements called "barangays". -

Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” the Yellow Peril, Mad Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, Mad Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books Nathan Vernon Madison Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, German Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books Nathan Vernon Madison Copyright © 2010 Nathan Vernon Madison Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, German Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of History at Virginia Commonwealth University by Nathan Vernon Madison Master of History – Virginia Commonwealth University – 2010 Bachelor of History and American Studies – University of Mary Washington – 2008 Thesis Committee Director: Dr. Emilie E. Raymond – Department of History Second Reader: Dr. John T. Kneebone – Department of History Third Reader: Ms. Cindy Jackson – Special Collections and Archives – James Branch Cabell Library Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December, 2010 i Acknowledgments There are a good number of people I owe thanks to following the completion of this project. -

The Intangible Warrior Culture of Japan: Bodily Practices, Mental Attitudes, and Values of the Two-Sworded Men from the Fifteenth to the Twenty-First Centuries

The Intangible Warrior Culture of Japan: Bodily Practices, Mental Attitudes, and Values of the Two-sworded Men from the Fifteenth to the Twenty-first Centuries. Anatoliy Anshin Ph.D. Dissertation UNSW@ADFA 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have seen the light without the help of more people than I can name individually. I am particularly grateful to Professor Stewart Lone, UNSW@ADFA, and Professor Sandra Wilson, Murdoch University, for their guidance and support while supervising my Ph.D. project. All of their comments and remarks helped enormously in making this a better thesis. A number of people in Japan contributed significantly to producing this work. I am indebted to Ōtake Risuke, master teacher of Tenshinshō-den Katori Shintō-ryū, and Kondō Katsuyuki, director of the Main Line Daitō-ryū Aikijūjutsu, for granting interviews and sharing a wealth of valuable material during my research. I thank Professor Shima Yoshitaka, Waseda University, for his generous help and advice. I would like to express my infinite thankfulness to my wife, Yoo Sun Young, for her devotion and patience during the years it took to complete this work. As for the contribution of my mother, Margarita Anshina, no words shall convey the depth of my gratitude to her. 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgements…………..…………………………………………………….……1 Contents…………………………..……………………………………………………...2 List of Illustrations……………………………………………………………………….5 Conventions……………………………………………………………………………...6 List of Author’s Publications…………………………………………………………….8 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………….9 -

Ancient Chinese Cash Notes - the World’S First Paper Money

ANCIENT CHINESE CASH NOTES - THE WORLD’S FIRST PAPER MONEY PART I John E. Sandrock China has had a long and diversified numismatic history. From the dawn of antiquity onward, early Chinese traders used money in one form or another. Ancient Chinese paper money has always held a fascination for me partly because, without question, it is the world’s oldest. Not only is the ornamental format of these ancient notes aesthetically pleasing, more importantly they represent an esoteric subject area into which few collectors have ventured. We know of them not only through rare surviving specimens, but also through ancient Chinese works on numismatics. These books occasionally illustrated the specimens under discussion, and in this way their history has been preserved down through the ages to the benefit of modern scholars. In recent years Chinese archeologists have had great success in documenting archeological sites in which ancient relics including coins and paper money have been found. The history of ancient Chinese paper money is, unfortunately, not a happy one. Initially the notes were accepted as a great convenience, partially because they were backed by cash reserves. Over time the authorities greatly abused and misused the right of note issue, sometimes for personal gain, until the notes became so inflated the people would not accept them. Paper notes were viewed by the peasantry as a form of supplemental taxation, as the government ultimately refused to acknowledge responsibility for cashing them. By the mid-15th century a popular uprising was in the making. To avoid rebellion, the Ming emperor Jen Tsung forbid further circulation of paper, thereby reverting to a specie economy. -

Philippine Studies Ateneo De Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines The Principalia in Philippine History: Kabikolan, 1790-1898 Norman G. Owen Philippine Studies vol. 22, nos. 3 and 4 (1974): 297-324 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Philippine Studies 22(1974): 297-324 The Principalia in Philippine History: Kabikolan, 1790-1 898* NORMAN G. OWEN Note on tmnscriptions: In the transcription of quotations and titles of documents in Spanish the following general rules have been observed. Documents which can be found by reference to archive numbers alone are cited without titles. When necessary for the location of the document (particularly in the National Archives of the Philippines), the title has usually been given in shortened form. The bureaucratic heading ("Diec- ci6n General de Administraci6n Civil," etc.) has been omitted, and the actual documentary title has been shortened (with omissions indicated by ellipees) to a length adequate for identification. In the portions quoted, the Spanish is given as it appears in the original so far as spelling and accentuation, both erratic, are concerned. -

I. Editorship Ii. Articles in Peer-Reviewed Journals Iii. Book Iv

Maria Khayutina I. EDITORSHIP II. ARTICLES IN PEER-REVIEWED JOURNALS III. BOOK IV. BOOK CHAPTERS V. ANNOTATED TRANSLATIONS VI. REVIEWS VII. ARTICLES IN EDITED JOURNALS, CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS, ALMANACS AND LEXICA Some of the publications listed below can be downloaded as PDF under https://lmu-munich.academia.edu/MariaKhayutina https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria_Khayutina I. EDITORSHIP EICHER , Sebastian und Maria KHAYUTINA (Hg.), Erinnern und Erinnerung, Gedächtnis und Gedenken: Über den Umgang mit Vergangenem in der chinesischen Kultur (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2020). KHAYUTINA , Maria (ed.), Qin - der Unsterbliche Kaiser und seine Terrakottakrieger (320 S.) Qin – the eternal emperor and his terracotta army Qin – l’empereur éternel et ses guerriers de terre cuite (Zurich: Neue Zürcher Zeitung Libro, 2013). II. ARTICLES IN PEER-REVIEWED JOURNALS forthcoming Beginning of Cultural Memory Production in China and Memory Policy of the Zhou Royal House During The Western Zhou Period (Ca. Mid-11th -Early 8th c. BCE), forthcoming in Early China 44. 2014 “Marital Alliances and Affinal Relatives ( sheng 甥 and hungou 婚購 ) in the Society and Politics of Zhou China in the Light of Bronze Inscriptions,” Early China 37, 1-61. 2010 “Royal Hospitality and Geopolitical Constitution of the Western Zhou Polity (1046/5 -771 BC),” T’oung Pao 96.1-3, 1-73. 2008 “Western ‘capitals’ o f the Western Zhou dynasty (1046/5 – 771 BC): historical reality and its reflections until the time of Sima Qian,” Oriens Extremus 47, 25-65. 2003 “Welcoming Guests – Constructing Corporate Privacy? An Attempt at a Socio - Anthropological Interpretation of Ancestral Rituals Evolution in Ancient China (ca. XI - V cc.