Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airir •Orce < Flies in Ito Fla Rl I It^ Tk at 1< Learinj

' G a rme r commilission propip o s e s f e e ih i k e s f o r ' licenses, taQSt — IQ2 n : . ■ I I ChZlaasificd JJY o u r l ~ Z T teae sh**ia sm whMi. ln l ' r a v e l p C S I , p nr e p h a r r ieler ^ snrraculile, like n«w. lell- fU i RabbitsI a t fair: >ntaffwd. llB»p« 6. mmlna lI i ’at i l e r , w - atc:^^b a Sl i e i r t e r ------------ r — j,< jpwvim K i d s l o v e ’e m - Er r r — g larketplace C( 3 , < d i i v rl I iT^ f ■ I.Uglcv!^^'«^|^r*lnc. 8 4 thh year,; N o. 250 Twin Falla, Idadaho Thursday. SepilepJember 7. 1989 B jRepiK)rt ■ criticicizes H ^ o o i 1^8 H jail states By CRAIG LINCOlITOLN ' I Timcs-Ncws n'riteiriter H j^M | manages its jailini in a ‘horribly inadequate" mnnilanner, and its legal liability from the jail is “extreme," • ■ according to a repreport submitted to a judge Wednesday.ny. _ A litnnyi f ccomplnints from T1m*»N*w« pnotaWKE; 9 AisDunY prisoners, includiiluding threats by jail ' ‘ a n d n1 _rere p jjrt f^rom a ja il • he feels the Air forcc Iss ‘f‘taking away my backtkyard* w hile speakingg Ibefore Air Force officiiIcials-W ednesday night. B uhlattorneiney Bob W eaver says hc expert outline proiproblems-at a facility that once was "state-of-the"st art." It I —nowdirectlj-violiviolates the rights of ... -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

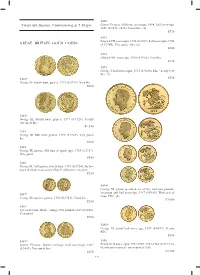

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2). -

The Warring States and Monetizing Economies

The Warring States and Monetizing Economies An Analogical Research on the Causal Relationships between Geopolitics, Economics, and the Emergence of the Round Coinage of China Tiivistelmä ”The Warring States and Monetizing Economies: An Analogical Research on the Causal Relationships between Geopolitics, Economics, and the Emergence of the Round Coinage of China” on Helsingin yliopiston arkeologian oppiaineen pro gradu –tutkielma. Se on kirjoitettu englannin kielellä. Pro gradussa tutkitaan syitä sille, miksi Kiinassa otettiin Itäisen Zhou-dynastian aikana (770 - n. 256 eaa.) käyttöön pyöreät pronssikolikot toisenlaisten rahamuotojen rinnalle. Tuolloin Kiina koostui vielä useasta itsenäisestä valtiosta, jotka olivat jatkuvissa sodissa toisiaan vastaan. Pro gradussa osoitetaan pyöreiden kolikoiden pääfunktion olleen näiden valtioiden kansalaisten harjoittaman päivittäis- ja paikallistason kaupankäynnin helpottaminen, jolla on ollut suuri merkitys paikallisyhteisöjen vaurauden ja omavaraisuuden ylläpitämisessä. Tällä on puolestaan ollut merkittävä rooli kansalaisilta kerättyjen verovarojen määrän maksimoinnissa. Verovaroilla oli puolestaan hyvin merkittävä rooli valtioiden armeijoiden ylläpidossa, joiden olemassaoloon valtioiden selviytyminen nojautui. Pyöreiden kolikoiden suuri merkitys Itäisen Zhou-dynastian valtioiden paikallis- ja valtiotason ekonomiassa osoitetaan lähestymällä aihetta kolmen eri tutkimuskeinon avulla. Näistä ensimmäisenä käsiteltävä koskee aikakaudella käytettyjen pronssirahatyyppien fyysisiä eroja. Näiden perusteella -

American Numismatic Society Summer Graduate Seminar 2010

American Numismatic Society Summer Graduate Seminar 2010 Chinese Numismatic References: an Annotated Bibliography Robert W. Hoge and Frederic C. Withington Naturally, most research in Chinese numismatics has been performed in China and published in Chinese, and unfortunately, not much of it has been translated into English. However, enough material has either been translated or written in English to meet the needs of everyone except the most serious specialists. China changed radically in 1912 with the fall of the Empire. Since then, Chinese coins and paper money have been typically modern in style, with the issues reflecting the country’s chaotic recent history. The following references, and the Seminar lecture, are largely devoted to pre-1912 numismatics. Most information about modern Chinese numismatics can be obtained from commonly used general catalogs. Bruce, Colin R. II, sr. ed. 2007. Standard catalog of world coins: eighteenth century, 1701-1800, 4th ed. Iola, Wis.: Krause Publ. All types and issues covered. -- 2004. Standard catalog of world coins: 1801-1900, 4th ed. Iola, Wis.: KP Books -- [2009]. 2009 Standard catalog of world coins, 1901-2000, 36th ed. [Iola,Wis.]: Krause Publ. Burger, Werner. 1964. Manchu inscriptions on Chinese cash coins. Museum Notes 11, p. 313-318, pls. 50-55. New York: American Numismatic Society. -- 1976. Ch'ing cash until 1735. Taipei, Taiwan: Mei Ya Publ. The definitive study of these multitudinous issues. Coole, Arthur Braddon. 1936. Coins in China's history. Tientsin, Hopeh, China: Student work department of the Tientsin Hui Wen Academy. (4th reprint ed., Quarterman Publ., 1965). Brief and comprehensive, it contains inaccuracies corrected in Hartill and Peng. -

Economic and Trade Relations with NOTES from the EDITORS 4 Leaders of These South Pacific Countries

Vol. 28, No. 14 April 8, 1985 JING ^^-^^^ A CHINESE WEEKLY OF NEWS AND VIEWS Deng Xiaoping on China's Second Revolution Research System Reforms Outlined North China's Largest Forestry Centre A view of the Saihanbo Forestry Centre. Farm workers water saplings. Covered with both dense forests and meadows, Saihanba is ideal for grazing livestock. Saihanba, an old Qing Dynasty hunting ground in Weichang County, Hebe! Province, has been turned into the largest forestry centre in north China. SPOTLIQHT HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WEEK Vol. 28, No. 14 April 8, 1985 Hu Yaobang to Visit South Pacific In his upcoming visit to Australia, New Zealand, Western CONTENTS Samoa, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea, Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang will discuss economic and trade relations with NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 leaders of these South Pacific countries. The trip is aimed at Hu's South Pacific Trip Holds deepening understanding, promoting friendship and seeking Promise extensive co-operation and lasting peace in the area (p. 4). LETTERS 5 EVENTS & TRENDS 6-10 Reform Is 'Second Revolution' Deng: Reform Is 'Second Revolu• Chairman of the Central Advisory Commission Deng Xiao• tion' ping recently termed the nation's ongoing economic reform a Sessions Discuss Congress Reports Ministers Chart Growth Plan "second revolution." "China is determined to carry through China Sets Free Its Rural Economy its current reforms and is firm on its internal and external Support Pledged for Sierra Leone open policies," said Deng (p. 6). Production of Energy Increases INTERNATIONAL 11-14 Zhao On Reform of Scientific System South Africa: World Condemns Massacres China today urgently needs to reform its science manage• Bangladesh: Policies Speed Eco• nomic Growth ment system. -

Report Title Xi, Baikang (Um 1979) Bibliographie : Autor Xi, Chen

Report Title - p. 1 of 235 Report Title Xi, Baikang (um 1979) Bibliographie : Autor 1979 [Maupassant, Guy de]. Mobosang duan pian xiao shuo xuan du. Mobosang ; Xi Baikang. (Shanghai : Shanghai yi wen chu ban she, 1979). [Übersetzung ausgewählter Kurzgeschichten von Maupassant]. [WC] Xi, Chen (um 1923) Bibliographie : Autor 1923 [Russell, Bertrand]. Luosu lun wen ji. Luosu zhu ; Yang Duanliu, Xi Chen, Yu Yuzhi, Zhang Wentian, Zhu Pu yi. Vol. 1-2. (Shanghai : Shang wu yin shu guan, 1923). (Dong fang wen ku ; 44). [Enthält] : E guo ge ming de li lun ji shi ji. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. The practice and theory of Bolshevism. (London : Allen & Unwin, 1920). She hui zhu yi yu zi you zhu yi. Hu Yuzhi yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Socialism and liberal ideals. In : Living age ; no 306 (July 10, 1920). Wei kai fa guo zhi gong ye. Yang Duanliu yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Industry in undeveloped countries. In : Atlantic monthly ; 127 (June 1921). Xian jin hun huan zhuang tai zhi yuan yin. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Causes of present chaos. In : The prospects of industrial civilization. (London : Allen & Unwin, 1923). Zhongguo guo min xing de ji ge te dian. Yu Zhi [Hu Yuzhi] yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Some traits in the Chinese character. In : Atlantic monthly ; 128 (Dec. 1921). Zhongguo zhi guo ji di wei. Zhang Wentian yi. [WC,Russ3] Xi, Chu (um 1920) Bibliographie : Autor 1920 [Whitman, Walt]. Huiteman zi you shi xuan yi. Xi Chu yi. In : Ping min jiao yu ; no 20 (March 1920). [Selected translations of Whitman's poems of freedom]. -

THE ARTS of CHINA Michael Sullivan

MICHAEL SULLIVAN Copyrighted ma: THE ARTS OF CHINA Michael Sullivan THE ARTS OF CHINA Third Edition University of California Press Berkeley • Los Angeles • London opyriyrutju mditjridi University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Copyright © 1967. 1973. >977. 1984 by Michael Sullivan. All rights reserved. Library ofCongress Cataloging in Publication Data Sullivan, Michael, 1916- Thc arts of China. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Art, Chinese. I. Title. N7340.S92 1983 709'. $1 82-16027 ISBN 0-520-04917-9 ISBN 0-520-04918-7 (pbk.) Printed in the United States of America I i Copyrighted material to Khoan Copyrighted material Contents List of Maps and Illustrations ix Preface to the Third Edition xix Chronological Tabic of Dynasties xxii Reign Periods of the Ming and Ch'ing Dynasties xxiii 1. Before the Dawn of History 1 2. The Shang Dynasty 12 3. The Chou Dynasty 31 4. The Period of the Warring States 40 5. The Ch'in and Han Dynasties 34 6. The Three Kingdoms and the Six Dynasties 85 7. The Sui and T'ang Dynasties 114 8. The Five Dynasties and the Sung Dynasty 141 9. The Yuan Dynasty 179 10. The Mini: 1 )ynasty 198 11. The Ch'ing Dynasty 223 12. The Twentieth Century 24S Notes to the Text 265 Books, for Reference and Further Reading 269 Index 273 Co 5 9 List of Maps and Illustrations MAPS 8 Pitcher. Ht. 29.7 cm. Excavated at Wei-fang. Shan- tung. People's Republic of China, page 10 1 Modern China, page xxi 9 Hsien steamer. -

Chinese Coin Guide - Ancient Knife and Spade Money SALES GALLERY GUIDE INDEX HOME CHINESE INDEX

chinese coin guide - ancient knife and spade money SALES GALLERY GUIDE INDEX HOME CHINESE INDEX ANCIENT CHINESE COINAGE 700 BC TO 255 BC This is a reference guide to the cast coins of China from the Zhou Dynasty, including knife and spade coins, not a listing of coins offered for sale (although a listing of examples we currently have available can be viewed on our Chinese coin sales catalogue). Images represent the types and may be larger or smaller than the actual coins. INFORMATION NEEDED FOR UNDERSTANDING EARLY CHINESE COINS http://www.cadvision.com/calcoin1/reference/china/china1.htm (1 of 38) [10/7/2002 8:56:16 AM] chinese coin guide - ancient knife and spade money The coinage of early China is poorly understood. This site puts forward our observations and ideas that have evolved over time from many different sources, combining them with ideas put forward by other numismatists. Some of our theories may eventually prove wrong and will have to be revised as new information becomes available, but it is our hope that we have moved a step closer to a genuine understanding of this complex series. We will be happy to hear from anyone who wishes to express their opinions on this subject, or can provide us with information that we are not aware of. WHAT QUALIFIES AS A TRUE COIN A true coin must meet three criteria. First, it must bear the mark of the issuing authority. Lacking this, the item is a form of primitive money, not a coin. Secondly, it must contain an intrinsic value bearing some relationship to the circulating value. -

The Monetary Systems of the Han and Roman Empires

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The monetary systems of the Han and Roman empires Version 2.0 February 2008 Walter Scheidel Stanford University Abstract: The Chinese tradition of supplementing large quantities of bronze cash with unminted gold and silver represents a rare exception to the western model of precious-metal coinage. This paper provides a detailed discussion of monetary development in ancient China followed by a brief survey of conditions in the Roman empire. The divergent development of the monetary systems of the Han and Roman empires is analyzed with reference to key variables such as the metal supply, military incentives, and cultural preferences. This paper also explores the “metallistic” and “chartalistic” elements of the Han and Roman currency systems and estimates the degree of monetization of both economies. © Walter Scheidel. [email protected] 1. Introduction Beginning in the third century BCE, the imperial unification of both East Asia and the Mediterranean gave rise to increasingly standardized currency systems that sought to establish stable means of payment. In both cases, the eventual monopolization of minting tied the success of these currencies to the fortunes of the state. Yet despite these basic similarities, substantial differences prevailed. While silver and later gold dominated the monetary economy of the Roman empire, the victorious Chinese regimes operated a system of bronze coinages supplemented by uncoined precious-metal bullion. This raises a series of questions. How did these differences arise, and why did they persist well beyond antiquity? How did the use of different metals affect the relationship between the nominal and intrinsic value of monetary objects? Did the minting of precious metals in the West and China’s reliance on copper determine overall levels of monetization? To the best of my knowledge, none of these issues has ever been addressed from a comparative perspective. -

Processes of Enlightenment

PROCESSES OF ENLIGHTENMENT Farmer Initiatives in Rural Development in China Promotor: Prof. Dr. N. E. Long Hoogleraar in de ontwikkelingssociologie Wageningen Universiteit Promotiecommissie: Prof. Dr. Ing. B. Jenssen University of Dortmund, Germany Prof. Dr. J. G. Taylor South Bank University, London U.K. Prof. Dr. L. E. Visser Wageningen Universiteit Dr. ir. N. Heerink Wageningen Universiteit PROCESSES OF ENLIGHTENMENT Farmer Initiatives in Rural Development in China Ye Jingzhong Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, prof. dr. ir. L. Speelman in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 11 oktober 2002 des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula Ye Jingzhong PROCESSES OF ENLIGHTENMENT Farmer Initiatives in Rural Development in China ISBN: 90-5808-730-1 Copyright 2002 by Ye Jingzhong For Zihan TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations viii Measures ix Acknowledgements xi 1 Relevance of the Research 1 2 Theoretical Review 13 3 Entering the Community and Building Trust 49 4 Building the Community Profile 81 5 Exploring Multifarious Farmer Development Initiatives 131 6 Identifying the Social and Cultural Components of Farmer Initiatives 167 7 Social Construction of the Process of Farmer Development Initiatives 201 241 8 Conclusion and Discussion 257 Appendices 269 Bibliography 275 Summary 281 Samenvatting 287 Curriculum Vitae LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Maps 50 1 Map of China 50 2 Sketch map of Pocang Township and the research community Figures 92 4.1 Organizational diagram of Nandugang -

The Middle Kingdom, As China Has Always Been Called by Its Inhabitants, Is Perhaps the World’S Most Influential Civilization

2000 YEARS OF COINAGE CTHE HMIDDLEI KINGDOMNA A 12-PIECE RETROSPECTIVE COLLECTION CERTIFICATE OF AUTHENTICITY The Middle Kingdom, as China has always been called by its inhabitants, is perhaps the world’s most influential civilization. In addition to gunpowder, paper, woodblock printing, and the magnetic compass—the so-called Four Great Inventions—China also invented or discovered silk, tea, playing cards, toilet tissue, fireworks, boat rudders, umbrellas, kites, porcelain, wheelbarrows, iron casting, hot air balloons, seismographs, matches, horse stirrups, acupuncture, herbal medicine, lacquer, paper money, mechanical clocks, and alcohol. Unlike the nations of Europe, Africa, India, or the New World, China was united in ancient times, during the semi-legendary Xia Dynasty (2100-1600 BCE). While it has both expanded and fractured a number of times since then, it has been unified more often than not. This is due in part to a culture and system of govern- ment established by the pre-Common Era dynasties, which imposed a strict hierarchy among various ancestral cults and standardized the writing script, weights, and measures. The first emperor of one of these early dynasties, the Qin—from which the Western word “China” derives—established the first unified currency, the Ban Liang, ca. 210 BCE, appropriating a design first introduced by the Zhou. This system was modified during the reign of the Han emperor Wang Mang (7-23 CE), whose bizarre bao huo monetary overhaul involved tortoise shells, cowries, gold, silver, and archaic spade money, in addition to new coins. This chaotic system wreaked havoc on the Chinese economy and ultimately doomed the Han, the great dynasty that had invented paper.