An Exploration of the Aftermath of Violent Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Together, Saving Lives

Working Together, Saving Lives Integrated Final Report 2010–2015 Health Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo Project Name: Integrated Health Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo Cooperative Agreement Number: AID-OAA-A-10-00054 Contact information in DRC: Avenue des Citronniers, No. 4, Commune Gombe, Kinshasa Chief of Party: Dr. Ousmane Faye, +243 0992006180 Contact information in the US: 200 Rivers Edge Drive Medford, MA 02155 Director, Country Portfolio: Kristin Cooney, Tel: +1 617-250-9168 This report is made possible by the generous funding of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement AID- OAA-A-10-00054. The contents are the responsibility of the Democratic Republic of Congo-Integrated Health Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Cover Photo: Warren Zelman Report Design: Erin Dowling Design Working Together, Saving Lives Final Report: The Integrated Health Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo 2010–2015 Integrated Health Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To acknowledge the roles of the many people Tuberculosis Program, the National Multisectoral Program who have contributed to this project, we borrow for HIV/AIDS Prevention, the National Program for the from African wisdom: If you want to go quickly, go Fight Against HIV/AIDS, the National Program on Diarrhea alone. If you want to go far, go together. There have Prevention, the National Program on Nutrition, the been times that we have needed to move quickly, National Communication Program for Health Promotion, but it never would have been possible without the National Reproductive Health Program, National the people who supported the project to go far. -

Directors Fortnight Cannes 2000 Winner Best Feature

DIRECTORS WINNER FORTNIGHT BEST FEATURE CANNES PAN-AFRICAN FILM 2000 FESTIVAL L.A. A FILM BY RAOUL PECK A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE JACQUES BIDOU presents A FILM BY RAOUL PECK Patrice Lumumba Eriq Ebouaney Joseph Mobutu Alex Descas Maurice Mpolo Théophile Moussa Sowié Joseph Kasa Vubu Maka Kotto Godefroid Munungo Dieudonné Kabongo Moïse Tshombe Pascal Nzonzi Walter J. Ganshof Van der Meersch André Debaar Joseph Okito Cheik Doukouré Thomas Kanza Oumar Diop Makena Pauline Lumumba Mariam Kaba General Emile Janssens Rudi Delhem Director Raoul Peck Screenplay Raoul Peck Pascal Bonitzer Music Jean-Claude Petit Executive Producer Jacques Bidou Production Manager Patrick Meunier Marianne Dumoulin Director of Photography Bernard Lutic 1st Assistant Director Jacques Cluzard Casting Sylvie Brocheré Artistic Director Denis Renault Art DIrector André Fonsny Costumes Charlotte David Editor Jacques Comets Sound Mixer Jean-Pierre Laforce Filmed in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Belgium A French/Belgian/Haitian/German co-production, 2000 In French with English subtitles 35mm • Color • Dolby Stereo SRD • 1:1.85 • 3144 meters Running time: 115 mins A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE 247 CENTRE ST • 2ND FL • NEW YORK • NY 10013 www.zeitgeistfilm.com • [email protected] (212) 274-1989 • FAX (212) 274-1644 At the Berlin Conference of 1885, Europe divided up the African continent. The Congo became the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium. On June 30, 1960, a young self-taught nationalist, Patrice Lumumba, became, at age 36, the first head of government of the new independent state. He would last two months in office. This is a true story. SYNOPSIS LUMUMBA is a gripping political thriller which tells the story of the legendary African leader Patrice Emery Lumumba. -

UN Security Council, Children and Armed Conflict in the DRC, Report of the Secretary General, October

United Nations S/2020/1030 Security Council Distr.: General 19 October 2020 Original: English Children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020 and the information provided focuses on the six grave violations committed against children, the perpetrators thereof and the context in which the violations took place. The report sets out the trends and patterns of grave violations against children by all parties to the conflict and provides details on progress made in addressing grave violations against children, including through action plan implementation. The report concludes with a series of recommendations to end and prevent grave violations against children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and improve the protection of children. 20-13818 (E) 171120 *2013818* S/2020/1030 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020. It contains information on the trends and patterns of grave violations against children since the previous report (S/2018/502) and an outline of the progress and challenges since the adoption by the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict of its conclusions on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in July 2018 (S/AC.51/2018/2). -

Policy Briefing

Policy Briefing Africa Briefing N°91 Kinshasa/Nairobi/Brussels, 4 October 2012. Translation from French Eastern Congo: Why Stabilisation Failed government improves political dialogue and governance in I. OVERVIEW both the administration and in the army in the east, as rec- ommended by Crisis Group on several previous occasions. Since Bosco Ntaganda’s mutiny in April 2012 and the sub- sequent creation of the 23 March rebel movement (M23), In the short term, this crisis can be dealt with through the violence has returned to the Kivus. However today’s crisis following initiatives: bears the same hallmarks as yesterday’s, a consequence of the failure to implement the 2008 framework for resolu- the negotiation and monitoring of a ceasefire between tion of the conflict. Rather than effectively implementing the Congolese authorities and the M23 by the UN; the 23 March 2009 peace agreement signed by the gov- the reactivation of an effective and permanent joint ver- ernment and the CNDP (National Council for the Defence ification mechanism for the DRC and Rwandan border, of the People), the Congolese authorities have instead only as envisaged by the ICGLR, which should be provided feigned the integration of the CNDP into political institu- with the necessary technical and human resources; tions, and likewise the group appears to have only pretend- ed to integrate into the Congolese army. Furthermore in the addition of the individuals and entities that support- the absence of the agreed army reform, military pressure ed the M23 and other armed groups to the UN sanctions on armed groups had only a temporary effect and, more- list and the consideration of an embargo on weapons over, post-conflict reconstruction has not been accompa- sales to Rwanda; nied by essential governance reforms and political dia- the joint evaluation of the 23 March 2009 agreement logue. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

Questions Concerning the Situation in the Republic of the Congo (Leopoldville)

QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE SITUATION IN THE CONGO (LEOPOLDVILLE) 57 QUESTIONS RELATING TO Guatemala, Haiti, Iran, Japan, Laos, Mexico, FUTURE OF NETHERLANDS Nigeria, Panama, Somalia, Togo, Turkey, Upper NEW GUINEA (WEST IRIAN) Volta, Uruguay, Venezuela. A/4915. Letter of 7 October 1961 from Permanent Liberia did not participate in the voting. Representative of Netherlands circulating memo- A/L.371. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, randum of Netherlands delegation on future and Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory development of Netherlands New Guinea. Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, A/4944. Note verbale of 27 October 1961 from Per- Togo, Upper Volta: amendment to 9-power draft manent Mission of Indonesia circulating statement resolution, A/L.367/Rev.1. made on 24 October 1961 by Foreign Minister of A/L.368. Cameroun, Central African Republic, Chad, Indonesia. Congo (Brazzaville), Dahomey, Gabon, Ivory A/4954. Letter of 2 November 1961 from Permanent Coast, Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Representative of Netherlands transmitting memo- Togo, Upper Volta: draft resolution. Text, as randum on status and future of Netherlands New amended by vote on preamble, was not adopted Guinea. by Assembly, having failed to obtain required two- A/L.354 and Rev.1, Rev.1/Corr.1. Netherlands: draft thirds majority vote on 27 November, meeting resolution. 1066. The vote, by roll-call was 53 to 41, with A/4959. Statement of financial implications of Nether- 9 abstentions, as follows: lands draft resolution, A/L.354. In favour: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, A/L.367 and Add.1-4; A/L.367/Rev.1. Bolivia, Congo Brazil, Cameroun, Canada, Central African Re- (Leopoldville), Guinea, India, Liberia, Mali, public, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo Nepal, Syria, United Arab Republic: draft reso- (Brazzaville), Costa Rica, Dahomey, Denmark, lution and revision. -

Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba PDF Book

DEATH IN THE CONGO: MURDERING PATRICE LUMUMBA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Emmanuel Gerard | 252 pages | 10 Feb 2015 | HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780674725270 | English | Cambridge, Mass, United States Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba PDF Book Gordon rated it it was ok Jun 13, This feud paved the way for the takeover by Congolese army chief Colonel Mobutu Sese Seko, who placed Patrice Lumumba under house arrest, guarded by his troops and the United Nations troops. I organised it. Wilson Omali Yeshitela. During an address by Ambassador Stevenson before the Security Council, a demonstration led by American blacks began in the visitors gallery. The Assassination of Lumumba illustrated ed. Sort order. This failed when Lumumba flatly refused the position of prime minister in a Kasa-Vubu government. It is suspected to have planned an assassination as disclosed by a source in the book, Death in the Congo , written by Emmanuel Gerard and published in If you wish to know more about the life story, legacy, or even philosophies of Lumumba, we suggest you engage in further reading as that will be beyond the scope of this article. As a result of strong pressure from delegates upset by Lumumba's trial, he was released and allowed to attend the Brussels conference. Paulrus rated it really liked it Jun 15, Time magazine characterized his speech as a 'venomous attack'. He was the leader of the largest political party in the country [Mouvement National Congolais], but one that never controlled more than twenty-five percent of the electorate on its own. As Madeleine G. -

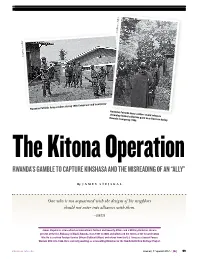

Kitona Operations: Rwanda's Gamble to Capture Kinshasa and The

Courtesy of Author Courtesy of Author of Courtesy Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers during 1998 Congo war and insurgency Rwandan Patriotic Army soldiers guard refugees streaming toward collection point near Rwerere during Rwanda insurgency, 1998 The Kitona Operation RWANDA’S GAMBLE TO CAPTURE KINSHASA AND THE MIsrEADING OF An “ALLY” By JAMES STEJSKAL One who is not acquainted with the designs of his neighbors should not enter into alliances with them. —SUN TZU James Stejskal is a Consultant on International Political and Security Affairs and a Military Historian. He was present at the U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda, from 1997 to 2000, and witnessed the events of the Second Congo War. He is a retired Foreign Service Officer (Political Officer) and retired from the U.S. Army as a Special Forces Warrant Officer in 1996. He is currently working as a Consulting Historian for the Namib Battlefield Heritage Project. ndupress.ndu.edu issue 68, 1 st quarter 2013 / JFQ 99 RECALL | The Kitona Operation n early August 1998, a white Boeing remain hurdles that must be confronted by Uganda, DRC in 1998 remained a safe haven 727 commercial airliner touched down U.S. planners and decisionmakers when for rebels who represented a threat to their unannounced and without warning considering military operations in today’s respective nations. Angola had shared this at the Kitona military airbase in Africa. Rwanda’s foray into DRC in 1998 also concern in 1996, and its dominant security I illustrates the consequences of a failure to imperative remained an ongoing civil war the southwestern Bas Congo region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Front Matter.P65

Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files CONGO 1960–January 1963 INTERNAL AFFAIRS Decimal Numbers 755A, 770G, 855A, 870G, 955A, and 970G and FOREIGN AFFAIRS Decimal Numbers 655A, 670G, 611.55A, and 611.70G Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A UPA Collection from 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Congo, 1960–January 1963 [microform] : internal affairs and foreign affairs / [project coordinator, Robert E. Lester]. microfilm reels ; 35 mm. Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Martin Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Congo, 1960–January 1963. “The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the U.S. Department of State in the custody of the National Archives of the United States.” ISBN 1-55655-809-0 1. Congo (Democratic Republic)—History—Civil War, 1960–1965—Sources. 2. Congo (Democratic Republic)—Politics and government—1960–1997—Sources. 3. Congo (Democratic Republic)—Foreign relations—1960–1997—Sources. 4. United States. Dept. of State—Archives. I. Title: Confidential US State Department central files. Congo, 1960–January 1963. II. Lester, Robert. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. United States. Dept. of State. V. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. VI. University Publications of America (Firm) VII. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Congo, 1960–January 1963. DT658.22 967.5103’1—dc21 2001045336 CIP The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the U.S. -

Rapport Final Des Experts De L'onu Sur La

Nations Unies S/2012/843 Conseil de sécurité Distr. générale 15 novembre 2012 Français Original : anglais Lettre datée du 12 novembre 2012, adressée au Président du Conseil de sécurité par le Président du Comité du Conseil de sécurité créé par la résolution 1533 (2004) concernant la République démocratique du Congo Au nom du Comité du Conseil de sécurité créé par la résolution 1533 (2004) concernant la République démocratique du Congo et en application du paragraphe 4 de la résolution 2021 (2011) du Conseil de sécurité, j’ai l’honneur de vous faire tenir ci-joint le rapport final du Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo (voir annexe). Je vous serais reconnaissant de bien vouloir porter à l’attention des membres du Conseil de sécurité le texte de la présente lettre et de son annexe et de le faire publier comme document du Conseil. (Signé) Agshin Mehdjiyev 12-59340 (F) 191112 201112 *1259340* S/2012/843 Annexe Lettre datée du 12 octobre 2012 adressée au Président du Comité du Conseil de sécurité créé par la résolution 1533 (2004) par le Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo Les membres du Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo ont l’honneur de transmettre ci-joint le rapport final du Groupe, établi en application du paragraphe 4 de la résolution 2021 (2011) du Conseil de sécurité. (Signé) Steven Hege (Signé) Nelson Alusala (Signé) Ruben de Koning (Signé) Marie Plamadiala (Signé) Emilie Serralta (Signé) Steven Spittaels 2 12-59340 S/2012/843 Résumé L’est de la République démocratique du Congo demeure la proie de dizaines de groupes armés congolais et étrangers. -

Africa: National Secvrity Files, 1961-1963

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY NATIONAL SECURITY FILES AFRICA: NATIONAL SECVRITY FILES, 1961-1963 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS Of AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of The John F. Kennedy National Security Files General Editor: George C. Herring AFRICA National Security Files. 1961-1963 Microfilmed from the holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Blair Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloglng-in-Publlcation Data The John F. Kennedy national security files. Africa [microform]. "Microfilmed from the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts; project coordinator, Robert E. Lester." Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick. Includes index. 1. Africa-National security-Sources. 2. United States-National security-Sources. I. Lester, Robert. II. Hydrick, Blair. III. John F. Kennedy Library. IV. University Publications of America. [UA855] 355'.03306 88-119 ISBN 1 -55655-001 -4 (microfilm) CIP ISBN 1-55655-003-0 (guide) Copyright® 1993 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-003-0. TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction•The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: "Country Files," 1961-1963 v Introduction•The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: Africa, 1961-1963 ¡x Scope and Content Note xi Source Note xii Editorial Note xii Security Classifications xiii Key to Names xv Abbreviations List xxix Reel Index Reel 1 Africa 1 Reel 2 Africa cont 15 Algeria 25 Reel 3 Angola 33 Chad.. ; 41 Congo•General 43 Reel 4 Congo•General cont 50 Reel 5 Congo•General cont 73 Congo•Cables 84 Reel 6 Congo•Cables cont , 98 m Reel 7 Congo•Cables cont :..: 129 Dahomey 146 Ghana 151 ReelS Ghana cont 155 Reel 9 Ghana cont 184 Guinea '194 Reel 10 Guinea cont 208 Ivory Coast 214 Libya 221 Mali 221 Morocco.. -

The Ruzizi Plain

The Ruzizi Plain A CROSSROADS OF CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE Judith Verweijen, Juvénal Twaibu, Oscar Dunia Abedi and Alexis Ndisanze Ntababarwa INSECURE LIVELIHOODS SERIES / NOVEMBER 2020 Photo cover: Bar in Sange, Ruzizi Plain © Judith Verweijen 2017 The Ruzizi Plain A CROSSROADS OF CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE Judith Verweijen, Juvénal Twaibu, Oscar Dunia Abedi and Alexis Ndisanze Ntababarwa Executive summary The Ruzizi Plain in South Kivu Province has been the theatre of ongoing conflicts and violence for over two decades. Patterns and dynamics of con- flicts and violence have significantly evolved over time. Historically, conflict dynamics have largely centred on disputed customary authority – often framed in terms of intercommunity conflict. Violence was connected to these conflicts, which generated local security dilemmas. Consequently, armed groups mobilized to defend their commu- nity, albeit often at the behest of political and military entrepreneurs with more self-interested motives. At present, however, violence is mostly related to armed groups’ revenue-generation strategies, which involve armed burglary, robbery, assassinations, kidnappings for ransom and cattle-looting. Violence is also significantly nourished by interpersonal conflicts involving debt, family matters, and rivalries. In recent years, regional tensions and the activities of foreign armed groups and forces have become an additional factor of instability. Unfortunately, stabilization interventions have largely overlooked or been unable to address these changing drivers of violence. They have mostly focused on local conflict resolution, with less effort directed at addressing supra-local factors, such as the behaviour of political elites and the national army, and geopolitical tensions between countries in the Great Lakes Region. Future stabilization efforts will need to take these dimensions better into account.